Key Findings

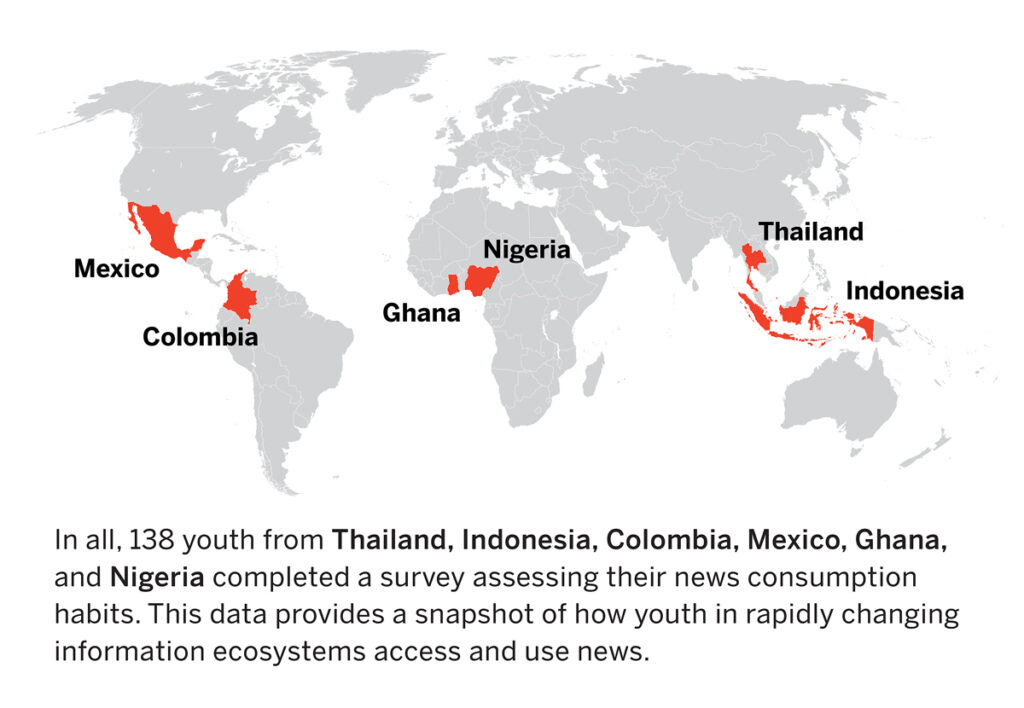

In the rapidly changing news ecosystems of emerging economies, news outlets are struggling to remain relevant and build loyal relationships with youth audiences (18 to 35 years old). As youth populations continue to grow in low-and-middle income countries, it is critical for independent media organizations to understand and respond to the changing news habits of younger generations. A snapshot of youth news consumption habits in Colombia, Ghana, Indonesia, Mexico, Nigeria, and Thailand highlights that the predominance of smartphones, and increasing access to the internet and social media, is fundamentally altering how youth access, interact with, and value independent news.

– Youth audiences tend to access news through their smartphone, relying more on social media algorithms and news aggregators than loyalty to particular news brands.

– Youth generally do not feel that the traditional, mainstream news media reports on issues that are important to them, preferring to access a wider variety of news alongside other kinds of information and entertainment.

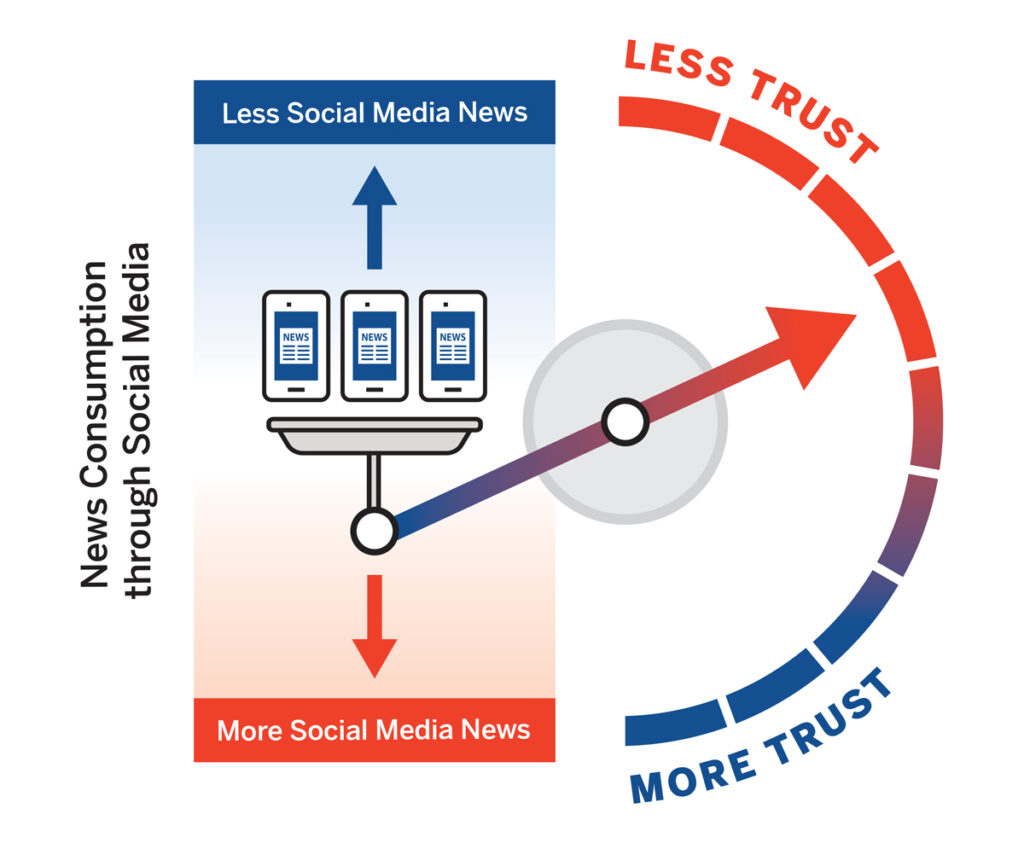

– Despite relying on social media for news, youth are wary about whether the information they see on the internet is true. There is a tension between the convenience social media provides for accessing news and its propensity to amplify misinformation and increase political polarization.

What do young people’s habits in developing countries tell us about the future of the news?

The space for independent media is shrinking in countries around the world. Growing restrictions on press freedoms, coupled with global changes in the economy of news brought on by rapid digitization, are making it difficult for media to operate independently and survive economically. These trends are most extreme in low- and middle-income countries, where small media markets and weak safeguards for independent media mean that news outlets are easily captured by powerful business or political interests. What do these trends mean for youth in countries around the world? How do they access high-quality independent information in rapidly changing news ecosystems? We asked them.

The messages that emerge from this study raise important questions for future research on youth, their access to independent news and information, and their news values in the rapidly developing economies of the Global South. The findings of this survey illustrate how new technologies and news preferences are emerging among youth in the countries surveyed, fundamentally altering the relationship between news producers and consumers. However, due to the small sample size, as well as the skew of respondents toward wealthier youth in urban areas, the findings of this survey cannot be considered representative of wider trends.

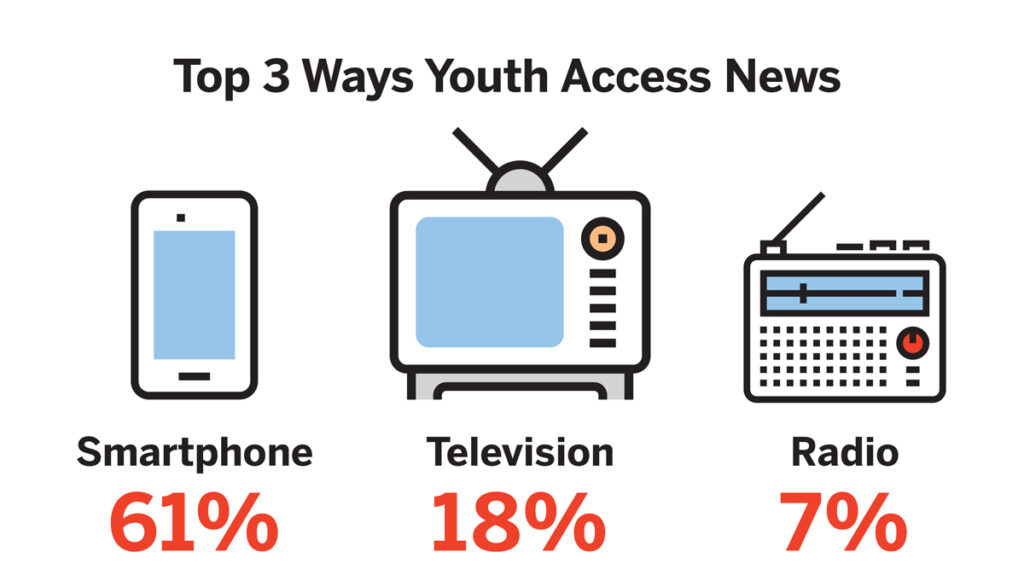

Chart 1 – Smartphone access is increasingly driving news consumption habits among youth

With increasing access to the internet through smartphones, young people are getting exposed to more news and information than ever before. Particularly in countries with slow or expensive internet connections, social media apps with zero-rated bandwidth that pull in personalized news content from multiple sources have grown in popularity.1

Across the countries surveyed for this study, the majority of youth report that they first reach for their smartphones to access news.

Data based on the first way respondents accessed news on the day they took the survey. Figures do not add up to 100 percent because some responses are not shown.

The bestselling smartphones in low- and middle-income countries come with operating systems preloaded with applications that show headlines from news sources chosen by their mobile network operator. On Android devices, for example, these content aggregators are one swipe from the home screen. For active news consumers, these apps connect young people with an array of news sources. For passive news consumers, these apps offer sentence-long abstracts, and a user can quickly scroll through the main headlines without reading the full articles.

The predominance of smartphones for accessing news and information is also reflected in similar studies. For instance, the latest Media Use in the Middle East survey shows that youth overwhelmingly turn to their smartphones to access news. In the Middle East, Egypt is the country with the lowest proportion of youth using smartphones for news access at 84 percent. Not surprisingly, youth are looking at news more frequently on their smartphones, with a majority accessing news at least once a day. Indeed, on the question of everyday access, smartphones beat out every other medium, including television.2

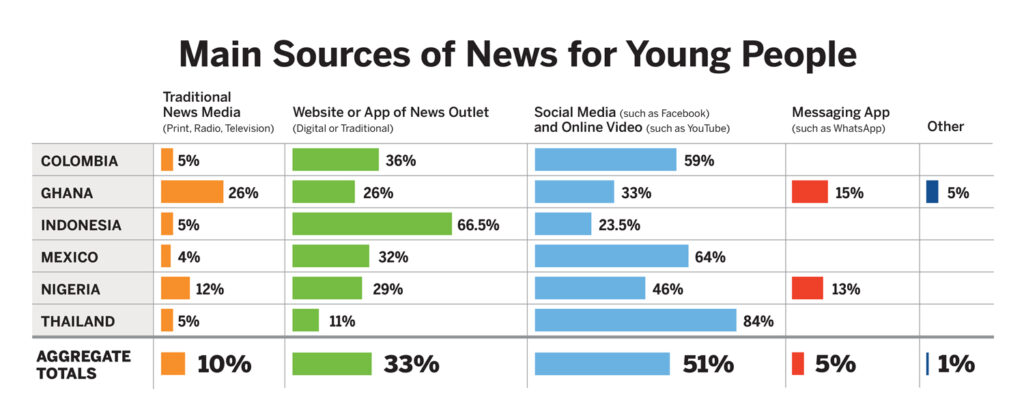

Chart 2 – Youth primarily get their news through social media

Rather than going directly to a news organization’s app or website, social media is the primary gateway to news in Colombia, Mexico, Nigeria, and Thailand. This suggests a shifting relationship between news outlet and audience. Traditionally, the news media maintained a direct relationship with their audiences—a news consumer would head directly to a newspaper, television network, radio outlet, or news website. This is not the case for 51 percent of the youth sampled, for whom algorithms—not editors—are the gatekeepers of news. In Ghana, legacy media outlets still have an advantage, though social media is quickly becoming a primary news source. Indonesian respondents largely reject intermediaries for news and information and prefer a direct relationship with a news producer.

The data from this study are confirmed by recent research from the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, which polled adults in 40 countries on their primary news sources. Some 70 percent of respondents in Argentina, Chile, Kenya, Mexico, and South Africa, and over 60 percent of respondents in Brazil and Malaysia, report using social media as a source of news on a regular basis. By comparison, in high-income countries, 40 percent of respondents indicate they primarily access news through social media.3 The prominence of social media networks as a source for news, particularly in the Global South, has been key to these platforms growing their user bases and accelerating engagement levels—the all-important metrics that these platforms use to pitch their relevance to advertisers.

This trend signals a shift in audiences’ relationships with news brands and with news content. These platforms are increasingly becoming a one-stop shop for news, entertainment, and social interaction. Be it through content aggregators or social media, young people typically “encounter the news rather than look for it.”4 News items are mixed into social media feeds alongside friend contributions, or appear as breaking news alerts when an app sends a notification. News accessed on mobile devices is often undifferentiated from other types of content. This is especially true of news accessed through social media, where what appears in a newsfeed is based on a chronological or algorithmic logic. As a result, it is possible that young people superficially engage with news as one of many ongoing digital engagements.

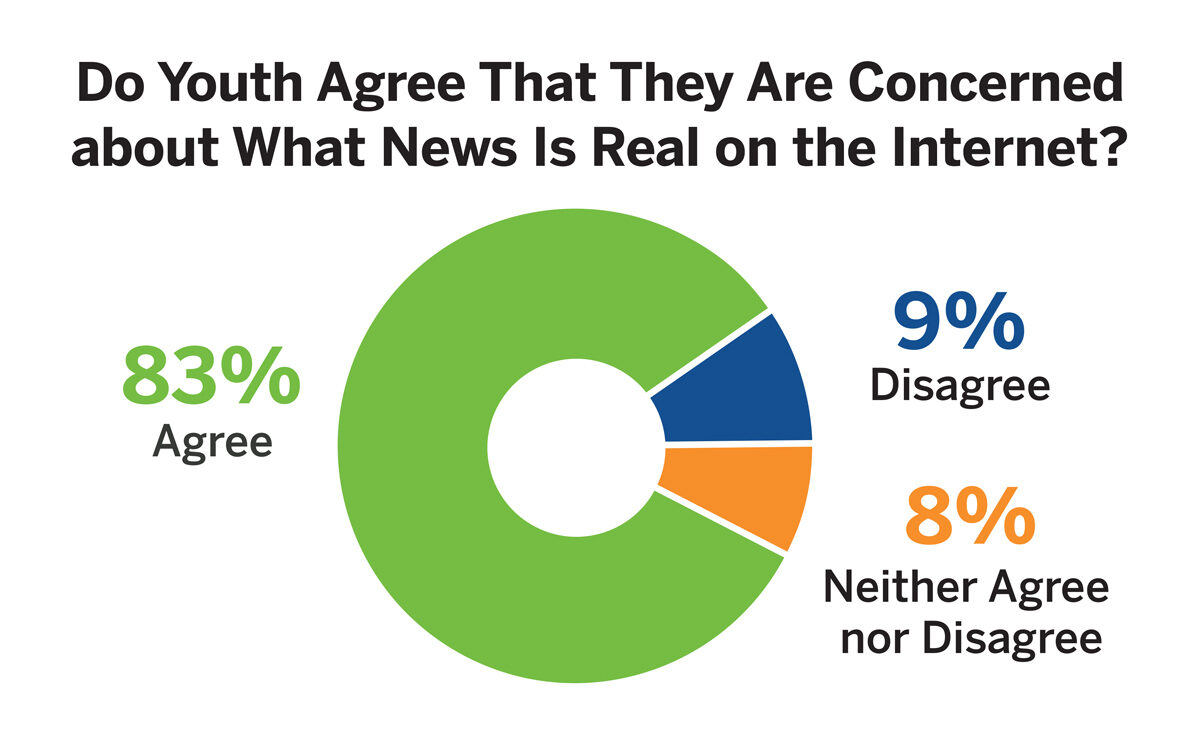

Chart 3 – Youth are skeptical about news they read on the internet

Despite the fact that the majority of youth surveyed rely on social media to access news, many of them do not trust what they see. They are acutely aware of the ability of these platforms to amplify misinformation and disinformation. 83 percent of youth who participated in this survey do not trust most of the news they see on the internet and overwhelmingly have concerns about whether the news they access is real.

Data collected by Afrobarometer in 2019 confirm this trend across 18 African countries surveyed. According to Afrobarometer, respondents overwhelmingly agree that social media keeps people more informed of current events and can help people have more of an impact on political processes. However, the majority of people also believe that social media is a predominant tool used to spread mis- and disinformation, and that people who use social platforms to access news on a regular basis are more susceptible to it.5

This love-hate relationship with news accessed through social media is difficult to reconcile and warrants further exploration. While youth have strong preferences for the ease of accessing news as part of their social media habits, they are at the same time acutely aware of social media’s ability to amplify false information and spread harmful content.

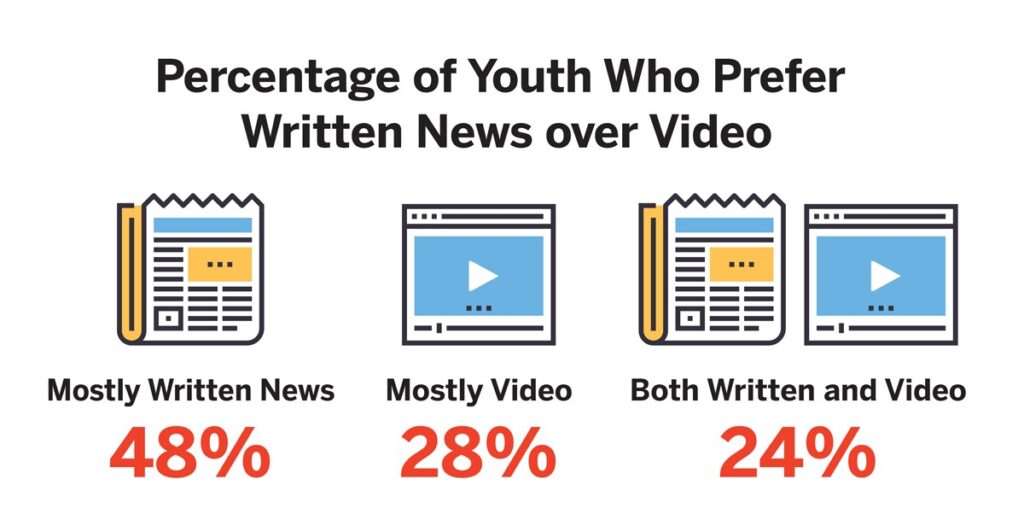

Chart 4 – Digital video formats are not a panacea for reaching youth audiences

The survey explored the extent to which youth audiences prefer to consume digital news content in video form rather than other formats. The findings raise the question of whether news outlets in these countries should “pivot to video”—reducing resources for written content in favor of video that is designed to be shared on social media platforms.6 This trend first took off among news publishers in the United States and was heavily promoted by Facebook, which tweaked its algorithm to prioritize video sharing.7 The popularity of social media platforms such as YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok among younger audiences might suggest that prioritizing video content is a must for a news outlet looking to grow its youth audience. However, respondents in this survey have a more mixed preference for video content.

While there is undeniably some demand for digital video news content in developing countries, there remains a pervasive digital divide.8 For this reason, many young people are either not interested in digital video content or not able to access it on a regular basis. In this survey, 12 percent of respondents had not recently watched any video content of any kind on the internet. Of those who had, 48 percent indicated that they mostly read news content in text format. Only 28 percent of respondents indicated that they mostly watch news in video form. The higher cost of cellular data in the countries included in the sample may partly explain why young news consumers still rely on less data-heavy text formats.9

Data based on answers from 122 respondents who indicated they had watched online video news over the last week.

This finding reflects recent research conducted by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, which shows that youth in high-income countries still seem to prefer text over video.10 Fifty-eight percent of individuals between 18 and 24 largely consume online news in text format. While this percentage was slightly lower than that for older respondents, it does show that even younger individuals still rely heavily on text. As the authors of that research noted, “video is not the way to engage young people, rather it is one of many formats that can engage [them].”

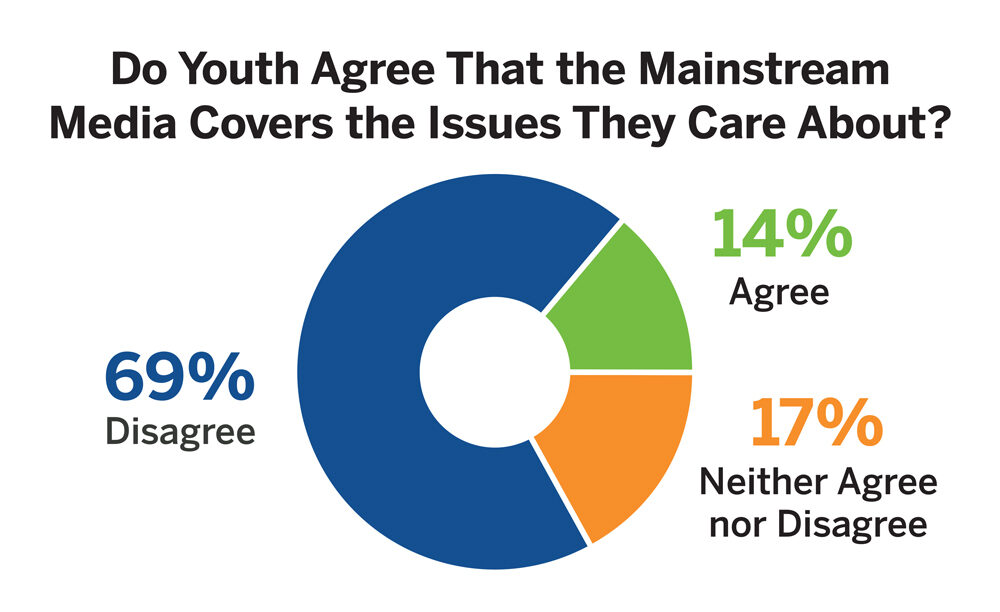

Chart 5 - Youth audiences and the dilution of news brands

In this survey, young audiences report that the stories they are interested in are rarely covered by mainstream media. This may be one reason why youth largely prefer to access a diverse array of news sources, rather than developing strong relationships with particular news brands.

This trend is also reported in other studies. Data from the Reuters Institute demonstrate that, across all countries surveyed, only 16 percent of youth (ages 18 to 24) go directly to the website or app of a news outlet to get their news.11

Similarly, young people interviewed for a study of youth news consumption in the United States and United Kingdom report that issues they are concerned about, including climate change and race relations, are not properly represented in mainstream media.12 Despite this lack of commitment to particular news agencies, this study shows that many young people still turn to certain “anchor news brands,” like BBC or CNN, for verification about a news report or event.13 Youth in this survey also named these outlets, along with some established local news outlets, among their main sources of news. This suggests that, similar to their peers in higher-income countries, youth in low- and middle-income countries continue to trust these brands for accurate news and information.

Youth engagement and the power of platforms

The trends outlined in this report highlight how large social media platforms are changing the traditional relationship between news producers and audiences, increasingly acting as intermediaries to accessing news content.14 As demonstrated in this survey, social media websites and apps are the primary ways young people access news in developing countries.

This changing consumption habit has important implications for media outlets and media support organizations. First, through moderation algorithms and processes, news on social media can potentially bypass the gates of traditional journalism.15 This gives the audience much more control over what they read, see, and hear, making them more vulnerable to clickbait articles and mis- and disinformation. Second, this changing relationship affects the ability of independent media outlets to monetize their content, as social media platforms dominate the advertising market. This loss of advertising revenue is having a critical impact on the financial sustainability of many news outlets.16

support organizations. First, through moderation algorithms and processes, news on social media can potentially bypass the gates of traditional journalism.15 This gives the audience much more control over what they read, see, and hear, making them more vulnerable to clickbait articles and mis- and disinformation. Second, this changing relationship affects the ability of independent media outlets to monetize their content, as social media platforms dominate the advertising market. This loss of advertising revenue is having a critical impact on the financial sustainability of many news outlets.16

Both of these concerns are deeply intertwined. Large platforms have the power to determine what content is seen or not seen by audiences. The process of amplifying the reach of particular content can also hide news that is uninteresting, controversial, insensitive, or unappealing to advertisers. This can lead to polarization as social media algorithms reinforce political views, giving youth less access to a diversity of perspectives.

This raises important challenges. How can news outlets develop strong brands and build trust with their audiences in this environment? These are just some of the issues that independent news outlets around the world are currently grappling with.

Why research on youth audiences is important

Research on this important demographic, particularly in emerging economies, is lacking. This is surprising given that in many countries, youth make up a significant portion of the population,17 and are important economic and political actors. How they consume news and information in rapidly changing news ecosystems will determine the future of the news industry in many countries. As such, greater attention needs to be paid to the news needs and expectations of youth to guide media policy and practice.

Research in high-income countries demonstrates the difficulty that news organizations are currently facing in adapting to an online environment, where easy access to numerous news sites means that audiences are less willing to pay for subscriptions.18 While some news organizations have adapted, they are struggling to monetize digital content, and to remain relevant to youth.19 Established news outlets in low- and middle-income countries are even more affected by these trends, threatening not only their ability to continue operating, but also their independence as they increasingly rely on advertising revenue from political sources.20 A better understanding of the new values, preferences, and consumption habits of youth can help media outlets prepare for and respond to these changes.

Research in high-income countries demonstrates the difficulty that news organizations are currently facing in adapting to an online environment, where easy access to numerous news sites means that audiences are less willing to pay for subscriptions.18 While some news organizations have adapted, they are struggling to monetize digital content, and to remain relevant to youth.19 Established news outlets in low- and middle-income countries are even more affected by these trends, threatening not only their ability to continue operating, but also their independence as they increasingly rely on advertising revenue from political sources.20 A better understanding of the new values, preferences, and consumption habits of youth can help media outlets prepare for and respond to these changes.

Avenues for future research

- The question of how new and small news outlets can build trust with youth audiences is an important one. As youth engage with news content in a more fluid way, it is increasingly difficult for news outlets to build a loyal audience among youth. Their concerns over the spread of mis- and disinformation further erode their willingness to trust digital news or less established news outlets. Additional research needs to be done to capture what smaller outlets in developing countries have done and can do to gain trust among this important demographic.

- Additional research on the relationship between publishers and platforms and its impact on youth news habits and values is important. Platforms have immense power to shape what content users have access to and what monetization options are available to news outlets. For this reason, it is critical to ensure that data on the impact of these trends on news ecosystems in the Global South are part of global discussions on platform governance.

Acknowledgements

The survey was conducted with help from TestingTime. The report was produced with contributions from members of CIMA’s editorial team: Heather Gilberds, Daniel O’Maley, and Malak Monir.

Footnotes

- Daniel O’Maley and Amba Kak, “Free Internet” and the Costs to Media Pluralism: The Hazards of Zero-Rating the News (Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance, 2018), https://www.cima.ned.org/publication/zero-rating-the-news/.

- Everette E. Dennis, Justin D. Martin, and Fouad Hassan, “Media Use in the Middle East, 2019: A Seven-Nation Survey” (Qatar: Northwestern University, 2019), www.mideastmedia.org/survey/2019.

- Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen, Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 (United Kingdom: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism and University of Oxford, 2020), https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2020-06/DNR_2020_FINAL.pdf.

- Pablo Boczkowski, Eugenia Mitchelstein, and Mora Matassi, “Incidental News: How Young People Consume News on Social Media,” Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 2017, https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstream/10125/41371/paper0222.pdf, 1785.

- Jeffrey Conroy-Krutz and Joseph Koné, Promise and Peril: In Changing Media Landscape, Africans Are Concerned about Social Media but Opposed to Restricting Access, Afrobarometer Dispatch No. 410, 2020, https://afrobarometer.org/sites/default/files/publications/Dispatches/ad410-promise_and_peril-africas_changing_media_landscape-afrobarometer_dispatch-1dec20.pdf.

- Heidi N. Moore, “The Secret Cost of Pivoting to Video,” Columbia Journalism Review, September 26, 2017, https://www.cjr.org/business_of_news/pivot-to-video.php.

- Trevor Hook, “Global Journalist: Did Facebook’s ‘Pivot to Video’ Cause Publishers to Face Plant?” KBIA, December 14, 2020, https://www.kbia.org/post/global-journalist-did-facebooks-pivot-video-cause-publishers-face-plant#stream/0.

- World Wide Web Foundation, “Covid-19 Shows We Need More than Basic Internet Access—We Need Meaningful Connectivity” (Washington, DC: World Wide Web Foundation, May 27, 2020), https://webfoundation.org/2020/05/covid-19-shows-we-need-more-than-basic-internet-access-we-need-meaningful-connectivity/; Alliance for Affordable Internet, Meaningful Connectivity: A New Target to Raise the Bar for Internet Access (Washington, DC: Alliance for Affordable Internet, 2020).

- Alliance for Affordable Internet, 2020 Affordability Report (World Wide Web Foundation, 2020), https://a4ai.org/affordability-report/report/2020/#what_is_the_state_of_internet_affordability_and_policy.

- Antonis Kalogeropoulos, “How Younger Generations Consume News Differently,” in Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2019, by Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Antonis Kalogeropoulos, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen (United Kingdom: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism and University of Oxford, 2019), https://www.digitalnewsreport.org/survey/2019/how-younger-generations-consume-news-differently/.

- Nic Newman, “Executive Summary and Key Findings of the 2020 Report,” in Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020, by Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen (United Kingdom: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism and University of Oxford, 2020), https://www.digitalnewsreport.org/survey/2020/overview-key-findings-2020.

- Kalogeropoulos, “How Younger Generations Consume News Differently.”

- Ibid.

- Emily Bell and Taylor Owen, “The Platform Press: How Silicon Valley Reengineered Journalism,” Columbia Journalism Review, March 29, 2017, https://www.cjr.org/tow_center_reports/platform-press-how-silicon-valley-reengineered-journalism.php.

- Gabrielle Tutheridge, “What Is the Role of Gatekeeping Journalist’s in Today’s Media Environment?” Medium, May 18, 2017, https://medium.com/@gabrielletutheridge/what-is-the-role-of-gatekeeping-journalists-in-today-s-media-environment-2034a30ba850.

- Jonty Bloom, “Coronavirus: How the Advertising Industry Is Changing,” BBC, May 27, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/business-52806115.

- Kristin Lord, “Here Come the Young,” Foreign Policy, August 12, 2016, https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/08/12/here-comes-the-young-youth-bulge-demographics/; United Nations, World Youth Report (New York: United Nations, 2020), https://www.un.org/development/desa/youth/wp-content/uploads/sites/21/2020/07/2020-World-Youth-Report-FULL-FINAL.pdf.

- Richard Fletcher, “Paying for News and the Limits of Subscription,” in Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2019, by Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Antonis Kalogeropoulos, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen (United Kingdom: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism and University of Oxford, 2019), https://www.digitalnewsreport.org/survey/2019/paying-for-news-and-the-limits-of-subscription/; Joshua Benton, “So Some People Will Pay for a Subscription to a News Site. How about Two? Three?” Nieman Lab, November 13, 2018, https://www.niemanlab.org/2018/11/so-some-people-will-pay-for-a-subscription-to-a-news-site-how-about-two-three/.

- Newman, “Executive Summary and Key Findings of the 2020 Report.”

- Marius Dragomir, Reporting Facts: Free from Fear or Favour (Paris: UNESCO, 2020); UNESCO, “Trends in Media Independence,” in World Trends in Freedom of Expression and Media Development: Global Report 2017/2018 (Paris: UNESCO, 2018), 102-129.