Introduction

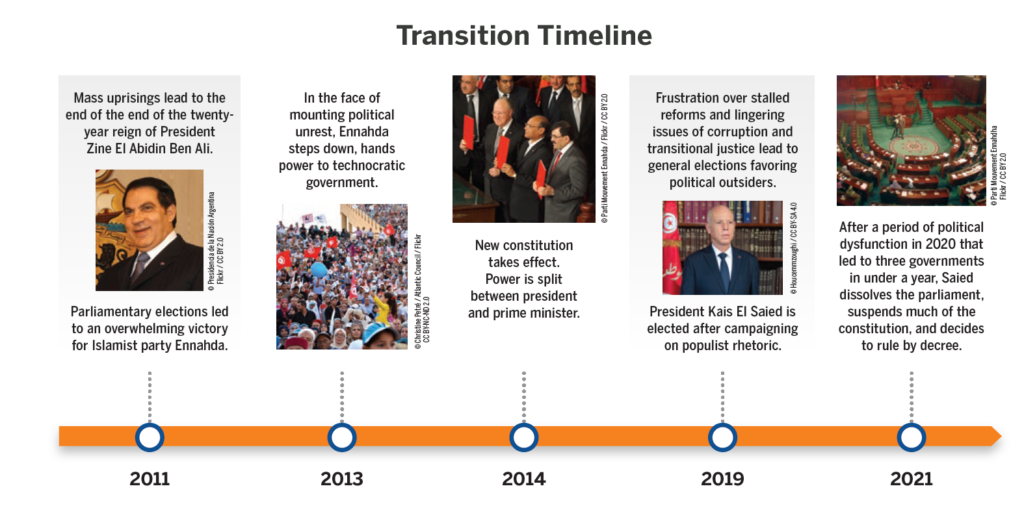

On July 25, 2021, Tunisian President Kais Saied dissolved parliament, suspended the prime minister, and announced that he would rule by emergency decree, marking a likely end to the North African country’s decade-long democratization era. The next day, Tunisian security forces raided and closed Al Jazeera’s Tunis bureau, ushering in the beginning of measures to roll back hard-won gains in media freedom and independence.

In 2011, things were different. The Jasmine Revolution that toppled longtime President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali led not only to democracy but also to a major reset of Tunisia’s media environment. A new and democratically elected government moved to guarantee freedom of expression, protect independent journalism, and establish new media regulators.1 Dozens of new print and broadcast outlets sprouted, internet restrictions were lifted, and reporters were able to present diverse political perspectives and openly criticize the government.

Tunisia’s media reform experience highlights the importance of democratic norm-building as a cornerstone of a sustainable and robust independent media system. Mistrust among political actors brought governance reform efforts to a halt long before Saied’s presidential power grab. Despite a strong civil society push and an outpouring of donor funding to the media in the years following the revolution, the Tunisian media environment is still marked by elements of the country’s authoritarian past.

Coalition-building among local stakeholders was hampered by uneven levels of capacity in the Tunisian civil society sector. In the absence of a coordinated local reform movement, donors set the agenda for media reform in ways that local experts say were disconnected from on-the-ground needs. This issue was compounded by a lack of political will for change due to constant partisan infighting, which brought any attempt at comprehensive legal reform to a standstill. Tunisia’s experience points to a need to build reform momentum through broader democratic governance reform and more equitable civil society support.

As the democratic reform window closes under the Saied government, there is renewed urgency to consolidate lessons learned from Tunisia’s decade-long effort to create an independent and pluralistic media environment. Based on interviews with 24 journalists, media-based civil society experts, and other stakeholders, as well as data from a focus group with journalists and politicians organized in Tunis in May 2019, this report is part of the Center for International Media Assistance’s “Media Reform amid Political Upheaval” series. By focusing on the period of media reform ushered in during Tunisia’s transition to democracy, this brief examines how civil society advocates, government reformers, journalists, and media experts worked together to build broad-based demand and support for independent journalism, and analyzes the role of international media assistance in propelling and sustaining these efforts. It provides recommendations for how the media development community can work with local advocates to protect the gains made and prepare for the next reform window.

The End of Ben Ali and Early Reforms

Under Ben Ali, the regime exerted great control over the press. State-owned broadcasters and the few privately held media outlets—often controlled by relatives of the president—offered a steady stream of praise for the authorities. The few newspapers that voiced criticism of the government faced censorship by Ben Ali’s Ministry of Communications, and journalists who strayed from the narrow band of acceptable reporting often faced harassment and attacks. Opposition websites and social media platforms were routinely blocked.2

The 2011 revolution ended many of these restrictions. The Ministry of Communications, which exerted broad control and censorship, was abolished. Media outlets owned by the Ben Ali family were confiscated and placed under the oversight of judicial administrators. The diversity of voices featured on the state-owned television channels Wataniya 1 and Wataniya 2 greatly expanded. Balanced representation of major political factions became a feature of news reporting by public broadcasters, especially in election coverage. The chief executive officer of the state broadcaster is now appointed through open competition following recommendations from the public broadcasting regulator. A merit-based process has also been implemented in selecting news editors at the state-owned wire service, Tunis Afrique Presse (TAP).

The 2011 revolution ended many of these restrictions. The Ministry of Communications, which exerted broad control and censorship, was abolished. Media outlets owned by the Ben Ali family were confiscated and placed under the oversight of judicial administrators. The diversity of voices featured on the state-owned television channels Wataniya 1 and Wataniya 2 greatly expanded. Balanced representation of major political factions became a feature of news reporting by public broadcasters, especially in election coverage. The chief executive officer of the state broadcaster is now appointed through open competition following recommendations from the public broadcasting regulator. A merit-based process has also been implemented in selecting news editors at the state-owned wire service, Tunis Afrique Presse (TAP).

In the push for democratization, a special commission known as the National Authority for Information and Communication Reform (INRIC) was established, and led by a group of human rights activists, journalists, and academic researchers. INRIC—together with journalists’ unions and civil society groups—sought to create the framework for a sustainable  transition to an independent and plural media. The work of this commission led directly to many of the reform movement’s successes—most of which came in the first three years after the fall of Ben Ali. The reforms generally followed international precedents, and were launched following broad discussions with Tunisian and international stakeholders.

transition to an independent and plural media. The work of this commission led directly to many of the reform movement’s successes—most of which came in the first three years after the fall of Ben Ali. The reforms generally followed international precedents, and were launched following broad discussions with Tunisian and international stakeholders.

The legal foundations for the reforms were established in important decrees approved by the country’s interim government less than a year after Ben Ali fled into exile.

The first, Decree 115, replaced the former regime’s press code and guaranteed freedom of expression and access to information. It also enshrined freedom of publication without prior license for print media and included clauses aimed at protecting media diversity and preventing monopolies. Prison time for media-related offences was abolished and replaced with fines.

The second, Decree 116, guaranteed the freedom of the broadcast sector and established an independent regulator—the High Independent Authority for Audiovisual Communication (HAICA)—to oversee the industry.

The third, Decree 41, enshrined the right to access information for journalists and the public in the interest of government transparency.

Several of these rights—the freedoms of opinion, expression, information, and publication—were further enumerated in Tunisia’s post-revolutionary constitution, adopted in 2014, which states that “these freedoms shall not be subject to prior censorship.”

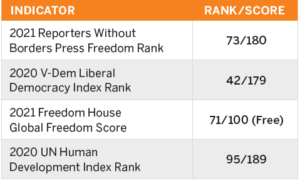

These changes greatly improved Tunisia’s information ecosystem, a fact reflected in international surveys. By 2015, Freedom House rated the country “free” in its annual Freedom in the World survey, and it remained the only Arab nation to hold this distinction until it was downgraded to “partly free” in 2022.

Fragile Gains: Challenges to Media Reform in the Post-Revolutionary Era

As significant as the changes were, progress slowed after 2014 as resistance from wealthy media owners and conservative politicians increased — resistance that had been undermining reforms even before Saied took power.

The independence of public media remained fragile and highly contested. Successive post-revolutionary governments sought to nominate senior staff, a practice used by Ben Ali’s government to control state media. The public broadcasting regulator, HAICA, repeatedly fought to maintain its ability to nominate the leadership of the public broadcaster. In April 2021, the new editor of the newswire TAP was forced to resign after a demonstration by dozens of journalists who objected to his appointment on the grounds that he was too close to the Ennahda Party, the largest in parliament.3

Efforts to influence public media were also indirect and channeled through the biases of individual journalists. “Most journalists continue to believe that personal connections with politicians are crucial for their roles,” said a former director of Tunisia’s state radio. “Leading journalists are in direct contact with those in power and discuss with them how they should tackle some polemic topics or who they should invite to their shows.”4

In addition, the legal underpinnings of the presidential edicts issued after the revolution were weak. Of the three executive orders, only Decree 41, dealing with access to information, was formally adopted as law by Tunisia’s parliament.

The other two key reform decrees, which created a new press code and provided a framework for regulating the broadcast sector, remain in legal limbo as parliament did not adopt them as law. Decree 115, protecting free expression, has been undermined by the ongoing use of Ben Ali–era laws in the penal code that criminalize some forms of speech. This has led to judicial ambiguity in the courts about which laws apply — as demonstrated by the 2018 prison sentence issued to blogger Amina Mansour for a Facebook post criticizing the government’s anti-corruption policies. While the 2014 constitution would appear to protect speech such as Mansour’s, the government’s failure to create a Constitutional Court to rule on the constitutionality of laws weakens such protections.

The broadcasting regulator, HAICA, has struggled to control a chaotic marketplace. Of the 14 TV channels operating in Tunisia, three were broadcasting illegally but with protection from other parts of the government.5 Further, HAICA has struggled to fulfill its mandate to review the financing of broadcast channels. After years of struggle with the central bank, it was not until 2019 that the regulator obtained access to key financial data about private media.

HAICA’s weakness explains some of the problems in Tunisia’s current television market, where at least four of the 12 privately owned television channels are or were recently owned by people associated with Tunisian political figures or factions. Several of these broadcasters have been operating illegally since before the revolution. Some of these cases are still under review; however, HAICA has so far not been successful in curbing the issue due to a lack of political support.

Prior to Saied’s anti-democratic steps in 2021, the greatest threat to the media environment was the growing use of broadcast outlets as political instruments. This is especially apparent among privately held television channels, which are active players in the political struggle among major political factions. “The problem is not the quantity of media programs but rather their quality,” said Tunisian journalist and TV anchor Elias el Gharbi. “Is the media content being produced for the service of the public interest or to assert the power of political lobbies and media owners?”6

Tunisia’s media-politics nexus is complex, and journalists enjoy greater agency than under Ben Ali. However, the focus of media — especially the highly influential political talk shows featured on TV — is on the struggle between political elites and major factions. This is to the detriment of smaller political parties and other groups. “We don’t hear all voices in media with the same diversity, scope and frequency as it used to be in the first phase of the transition,” said one former member of parliament from the Afak Tounes Party during a 2019 meeting. “There is no blackout on information. We can always voice opinions through various platforms, but being present on major TV stations is becoming very difficult.”7

The business model for these channels is heavily reliant on wealthy businesspeople with political ambition or on advertisers who may try to influence coverage. This makes independence from politics difficult, says Zuhair Latif, a journalist and owner of Telvza TV. “The funding forces us to take sides and to invite some figures to talk shows and ignore others,” he said. “If we want to be independent from all camps, we will find ourselves outside the game.”8

Role of International Media Assistance

Since the 2011 revolution, Tunisia has received significant foreign assistance for media development. Current aid is estimated at approximately $14.5 million to $17 million annually. Among the most significant programs is the European Union support program for media operated in partnership with the Tunis-based Centre Africain de Perfectionnement des Journalistes et Communicateurs (CAPJC). This program focuses on training journalists, conducting research, and building institutional capacity.

Media reform stakeholders credited the CAPJC program and others with raising journalists’ awareness in areas such as human rights, a major new field of investigation. The programs were also praised for providing journalists with knowledge about new challenges, such as reporting on the COVID-19 pandemic and how to counter the spread of disinformation.

However, some civil society representatives questioned whether such programs were an efficient use of funds, given their high costs, limited impact, and disconnect from Tunisian media organizations.

“There is no comprehensive evaluation of these programs to effectively test their impact,” said Nesrine Jelalia, head of Al-Bawsala, a Tunisian nonprofit focused on governance. “We can observe some change in media practices, but it is not proportional to the investments that were put in this sector.”9

Local experts noted the lack of coordination among international assistance actors as a major challenge in Tunisia. There is no mechanism to bring together the major funders and implementers with active projects in the country, which has led to a proliferation of fragmented, short-term training initiatives that are often divorced from the needs of local media organizations. As a result, these programs have failed to produce a tangible impact on the practice of journalism in Tunisia, which retains features of the country’s authoritarian past 10 years after the Jasmine Revolution.

While some donors do consult with their local partners and adapt their programs based on those discussions, this process remains flawed. Decisions on whether and how to modify a program’s planned features are made at the donor’s or implementer’s main office and generally do not deviate too far from the project’s original goals. In addition, as noted by ARTICLE 19’s regional director for Middle East and North Africa (MENA), Saloua Ghazouani Oueslati, it can be difficult to determine how to respond to local demand when different factions express different priorities.

“…What one side sees as a priority may not be for the other,” Oueslati said. “Moreover, these expectations are not necessarily reflective of the priorities of Tunisian audiences; therefore, most of the programs try find a mid-way to reconcile different views.”10

Although donors have made efforts to foster institutional-level media reform in Tunisia by supporting bodies like INRIC and HAICA, public media, and civil society,11 the lack of political will has proven to be an obstacle to lasting change.12

Recommendations and Conclusions

President Saied’s moves to undermine constitutional governance and Tunisia’s parliament pose a major challenge for further media reforms. Yet, should the political environment prove enabling, foreign donors, media assistance organizations, and other stakeholders should prioritize working with local stakeholders to find ways to navigate Tunisia’s chaotic media regulatory environment.

One focus of this effort should be on stabilizing and strengthening broadcast regulation. The legal ambiguity surrounding the 2011 post-revolutionary decree that established HAICA has undermined its legitimacy and effectiveness, contributing to the instrumentalization of broadcast stations as arms of politicians. In the words of Telvza TV’s Latif, the regulator is little more than a “kind policeman.” Its power is largely limited to issuing fines for egregious abuses, such as airing racist content, but is insufficient to impact more systemic problems.

Moreover, Tunisia’s 2014 constitution calls for HAICA to perform its duties only until parliament establishes a new regulatory body, the Audio-Visual Communication Commission. More than seven years later, Tunisia’s parliament has not done so, leaving HAICA as a lame duck. The adoption of a new broadcast law establishing the framework of the new commission is a major battle for media reformers. It is crucial that such a law vest the new regulator with wide powers to oversee ownership transparency, funding, and political linkages between officials and media owners.

The question of independence of the new regulator is also vital. The constitution calls for parliament to choose members of the new commission, a system that risks politicization. HAICA has proposed that parliament choose from names proposed by representative professional bodies to ensure the new commission is technocratic rather than political in nature. International media assistance donors and implementers must strengthen their cooperation with local media experts and civil society organizations to effectively apply pressure on leading political actors.

Along with HAICA, the Union for Journalists and the Press Council, a self-regulatory body, are seen as champions of media reform. They are buttressed by Tunisia’s robust civil society. While the movement has proven effective in shaping policy, the pro-reform coalition is informal and has mostly succeeded at warding off repressive initiatives rather than advancing new and progressive reforms. Where appropriate, international stakeholders can buttress this movement by further exerting diplomatic pressure, building the advocacy and public outreach capacity of organizations championing media reform, and potentially aiding the formation of a more formal coalition.

Given Tunisia’s current political fragmentation and economic malaise and the authoritarian tilt of President Saied, progress on these fronts may be slow and halting. Short-term priorities need to focus on protecting existing achievements, which are under threat. Despite these challenges, media development actors need to work with local advocates to strengthen cooperation and build consensus on media sector priorities that could be advanced when the political climate again makes reform possible.

For instance, to ease the influence of partisan politics on news coverage, media stakeholders, including international donors, should bolster efforts to promote self-regulatory bodies and empower them with adequate resources. Channeling resources to the Press Council, which was established in 2020 and has suffered from a lack of funding, is one potential avenue for support. Working with independent media outlets to find sustainable business models should lessen their dependence on donors and provide pathways to avoid capture by deep-pocketed politicians and businesspeople. The most challenging task remains, however—the need to bolster journalists’ autonomy by launching much-needed discussions on the dangerous political parallelism of Tunisian media, which has mostly been embedded by journalists as part of their professional identity.

Although the future of Tunisia’s democratic transition is uncertain, support for media development remains crucial. Political openings come and go, and policy windows open and close. International assistance actors should work with local partners to strengthen their capacity for collective action to more effectively push for institutional reform when the next opportunity arises.

Header Photo Credit: Dodos Photography / CC BY-SA 4.0

To read the working paper for this case study, as well as the synthesis report and the other country case studies, please see the project landing page here.

Footnotes

- Kamel Labidi, “Tunisia’s Media Barons Wage War on Independent Media Regulation,” in In the Service of Power: Media Capture and the Threat to Democracy, Anya Schiffrin, ed., (Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance, 2017), 125.

- Freedom House, Freedom of the Press 2009 – Tunisia (Washington, DC: Freedom House, 2009).

- “New Head of Tunisia’s State News Agency Resigns after Protests,” Reuters, April 19, 2021.

- Abdel Razzak Tabib, in an interview with the author, May 2021.

- Nouri el-Lajmi, head of HAICA, in an interview with the author, February 2020.

- Elias el Gharbi, in an interview with the author, February 2020.

- Rym Mahjoub, former member of parliament for the Afak Tounes party, in a focus group organized in Tunis, May 2019.

- Zuhair Latif, in an interview with the author, May 2021.

- Nesrine Jelalia, in an interview with the author, May 2021.

- Saloua Ghazouani Oueslati, in an interview with the author, May 2021.

- Institute for Integrated Transitions, “Inside the Transition Bubble: International Expert Assistance in Tunisia,” (Barcelona: Institute for Integrated Transitions, 2013), https://ifit-transitions.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Inside-the-Transition-Bubble-International-Expert-Assistance-in-Tunisia.pdf, 13.

- Labidi, “Tunisia’s Media Barons Wage War on Independent Media Regulation.”