Key Findings

The 1991 adoption of the Windhoek Declaration in Namibia ushered in a continent-wide commitment to supporting independent media in Africa. Despite initial progress, including the establishment of the regional Media Institute for Southern Africa (MISA), independent media in the region continues to suffer. Increasing attacks on independent journalism, the co-option of media outlets by political and economic interests, and the growing problem of disinformation is compromising the viability of independent media in the region. The strong foundation of regional cooperation in Southern Africa that began at Windhoek has also suffered. However, there remains strong enthusiasm among media actors in Southern Africa to reignite a regional network to promote solidarity, address the myriad challenges independent media in the region face, and articulate an African vision and agenda for media development.

– A regional coalition can help set norms and standards for democratic media by tapping into the leverage points and frameworks of regional institutions and amplifying national-level priorities in regional and global debates.

– Countries with stronger environments for independent media can support the reform agendas of restrictive countries through knowledge sharing and joint advocacy.

– For a coalition to be effective, it needs clear goals and a decentralized structure that avoids imposing hierarchy or encouraging unhealthy competition over funding.

‘We’re Stronger Together’: Cooperation for Media Reform in Southern Africa

Independent media are a critical component of democracy and sustainable development in Africa. Achieving African development goals, such as good governance, economic prosperity, and poverty reduction, depends on defending and deepening the role of the news media as sources of reliable information and platforms for citizen voices. These goals can best be achieved when independent media organizations, activists, and proponents of media freedom work together toward common aims. Regional approaches—where advocates from different countries come together to create platforms for collective action rooted in local demands—can be a successful way to address the myriad challenges faced by independent news media in Southern Africa.

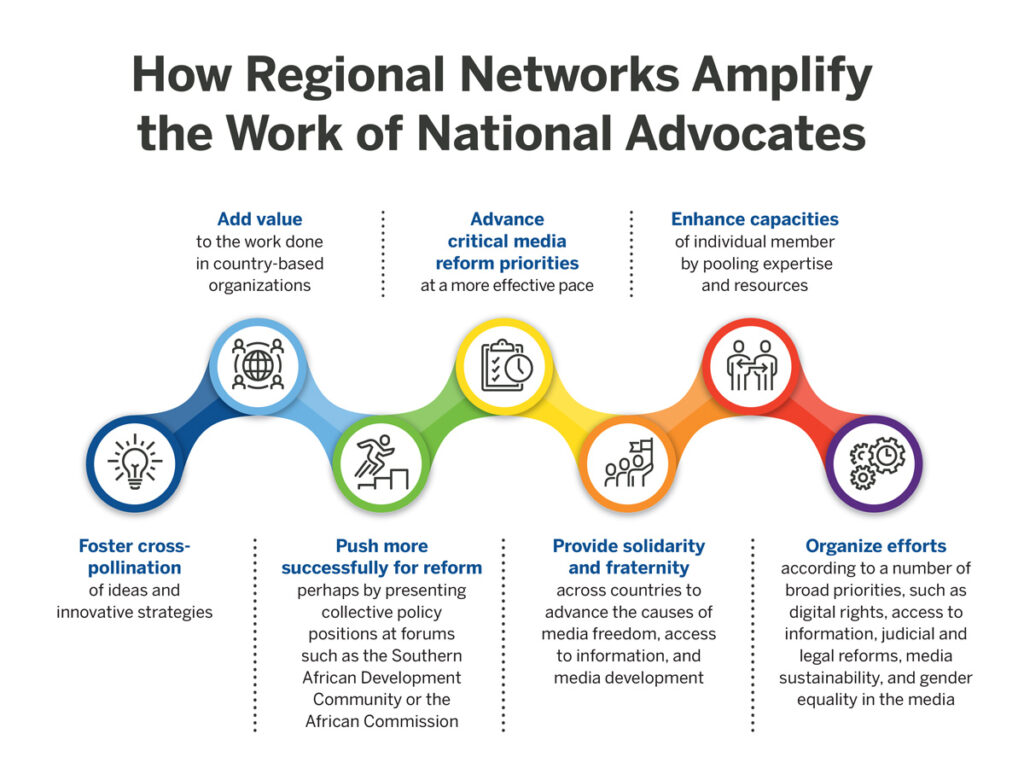

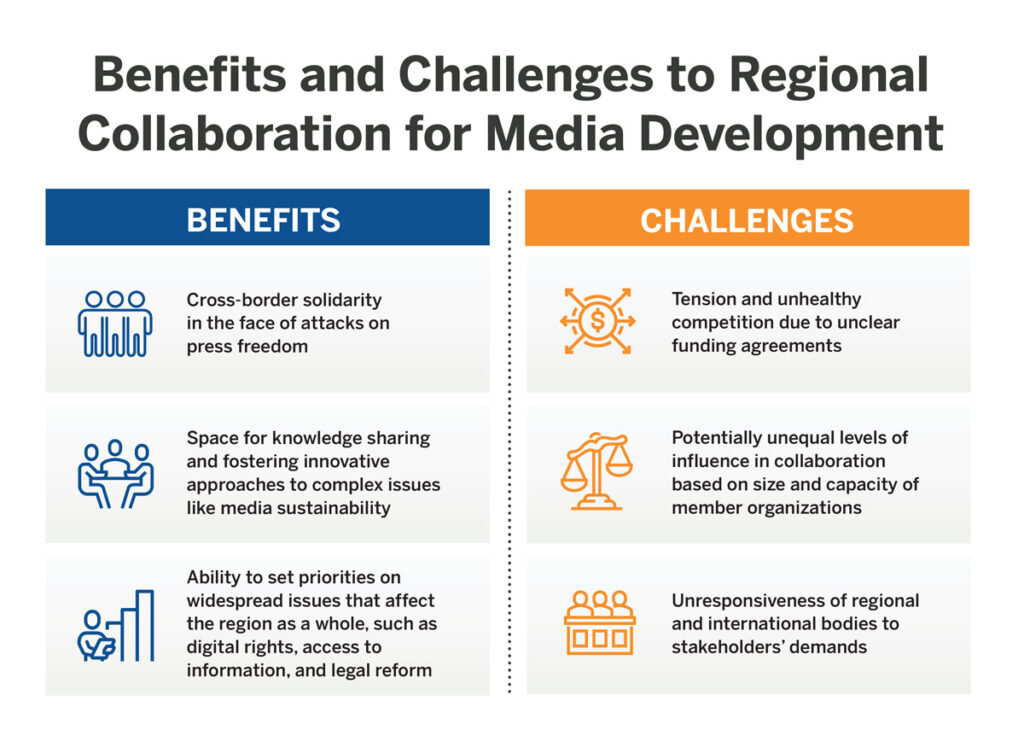

In the face of the many political, social, and economic challenges—and threats—to media systems in Southern Africa, viable coalitions of stakeholders in the media and civil society can play a vital role. These challenges include weak policy frameworks, small media markets, and political interference, all of which hinder the media’s ability to operate independently and in the public interest. When stakeholders from different spheres of work come together to define a common set of priorities and actions, regional coalitions can be formed to help enable a flourishing, independent, and public-oriented media. These stakeholders might include legislators, human rights defenders, journalists, media managers, and others who can create synergies to better withstand the many political and economic pressures facing the sector. Effective regional cooperation can help independent media reform movements gain traction by building solidarity across borders and leveraging the power of regional institutions to build political will for legal reforms. Regional cooperation has been seen as beneficial in other spheres like governance, trade, and industrialization, as such integration can help countries develop their economic capabilities and make them globally more competitive.1

Participants at a consultation of regional media stakeholders in Durban in July 2017. Photo Credit: Paul Rothman

At a time of growing challenges to the media sector, this report looks at regional cooperation as a critical tool for dealing with the complex and highly fragmented media sector reform agenda in Southern Africa. It examines lessons learned from previous collaborative efforts in the region, and the potential benefits of and challenges to this approach to media development. Local stakeholders who participated in this research have highlighted the local demand for such collaboration, especially as a means of better articulating their needs and perspectives in global debates. This report identifies a set of best practices and makes a series of recommendations about how such cooperation can be structured in order to effectively advance its agenda.

Cross-border coalitions on the continent have been previously identified as a way to promote robust and independent media. In West Africa, a strategy for coordination in the media sector included a wide variety of stakeholders—including civil society organizations, media actors, allies in government, and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS)—working together to advance common aims.2 In sub-Saharan Africa, advocates stress the need to build a multistakeholder network of non-state actors working with governments, parliamentarians, regional and international bodies, regulators, and others to support a conducive legal, regulatory, and economic environment for media.3

Such coalitions can be especially vital when media are under attack from governments at the national level. In these cases, a regional network can provide the solidarity and collective activism needed to confront national governments about their incursions into media freedom. When national media are under threat, a regional coalition can activate networks of human rights organizations, legal resources, faith-based and community organizations, and private sector stakeholders to provide a coordinated and multifaceted response at local, regional, and continental levels. Moreover, such a network could leverage the expertise of its members, providing a platform to share knowledge and resources on critical issues for the development and sustainability of independent media, such as legal reforms, media sector capacity building, and market dynamics.

The benefits of such collaboration are especially amplified in smaller, less developed countries. In Southern Africa, less developed countries such as Malawi, Mozambique, and Angola could leverage a network to benefit from countries with greater capacity and clout in regional and international policymaking forums. Regional coalitions also provide unique benefits to countries with authoritarian governments and closed media systems, such as Zimbabwe and Eswatini. Such countries have much to gain from their inclusion in regional conversations on the norms and standards necessary to govern democratic media, including the ability to draw on the solidarity of their regional allies when advancing their own advocacy agendas. Coalitions could also provide strategic leverage for such countries by establishing regional standards, and more democratic members of the network could apply pressure on authoritarian neighbors to implement media reforms. This leverage could also take the form of lobbying with regional policymaking bodies such as the Southern African Development Community (SADC) of the African Union.

In light of the challenges and opportunities for media sector development and media reform in Southern Africa, representatives from a variety of independent media advocacy organizations and self-regulatory institutions participated in a consultative research effort that aimed to answer the following questions:

- How can a coalition of media organizations, civil society actors, advocacy platforms, and funders better enable a coherent, impactful, and sustainable regional response to the challenges facing independent media in Southern Africa?

- What priority areas are most conducive to regional cooperation?

- What can be learned from prior regional efforts or successful cooperation in other regions about how best to mobilize and support such cooperation?

Consultation Methodology

The consultative research took place in several interlinked phases.

1. A background document summarized previous meetings focused on regional cooperation for media reform, including the participants and outcomes of these engagements.

2. A steering group made up of organizations involved in prior meetings reviewed the summary and participated in a workshop to co-design the research questions and methodology.

3. Key actors in the region completed a questionnaire and participated in a series of focus group discussions facilitated by the author. Additional key informant interviews triangulated the findings and gave additional depth to insights derived from the questionnaire and focus groups. In order to allow stakeholders to speak freely, all participants are anonymous.

4. Key findings from these engagements were analyzed and synthesized.

Research participants were recruited from organizations that have been extensively involved in prior network-building forums and, as such, have a keen interest in building and sustaining a regional network. In line with the consultative and participatory nature of the research, participants supported the research design and process from the very start. They helped shape the research questions, provided input into the methodological design, and assisted with a snowball-type sampling of other participants. Such a consultative and deliberative research process helps ensure that the research is relevant and responsive to the needs of the participants and focused on outcomes that are useful to their efforts. By facilitating a consultative process that enabled deliberation on challenges and visions for regional cooperation, the findings and recommendations are rooted in the demands of local actors, and the opportunities and constraints presented by local dynamics. The table below outlines the organizations that participated in the research.

From the Windhoek Declaration to Today

Southern Africa is a complex and diverse subregional bloc of sub-Saharan Africa. The countries that make up the region have a shared history, and numerous cultural, social, and economic similarities. These similarities along with their geographical proximity are a strong enabler for regional cooperation. Historically, countries in the region worked together as the Southern African Development Coordination Conference (SADCC)4 to advance political liberation in the region and reduce dependence on apartheid-era South Africa. In the 1990s, the SADCC was restructured as the SADC, comprised of the following countries: Angola, Botswana, Comoros, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Eswatini, Lesotho, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Seychelles, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Many of these countries are also represented in regional media bodies, such as the Southern African Editors’ Forum (SAEF) and the Media Institute of Southern Africa (MISA).

One of the earliest examples of such regional collaboration for media freedom and independence was the landmark Windhoek Declaration of 1991.5 This declaration by African journalists, later endorsed by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), was the outcome of regional deliberations to address the common threats faced by African journalists at the time: intimidation, censorship, and imprisonment, as well as practical problems such as lack of equipment and training. This declaration formed the cornerstone of subsequent regional collaborations and provided inspiration for further collaborative efforts to strengthen media independence in the region.

One of the most successful outcomes to emerge from this effort was the establishment of the Media Foundation for West Africa (MFWA). MFWA is the biggest and most influential advocacy organization on the continent and has led several successful campaigns for freedom of expression, media professionalism, peace-building, and participatory governance. One critical driver of the success of MFWA has been its ability to tap into existing regional institutions like ECOWAS. ECOWAS had adopted protocols and declarations to protect independent media and advance press freedoms, which enabled MFWA to tap into a well of broader, regional support.6

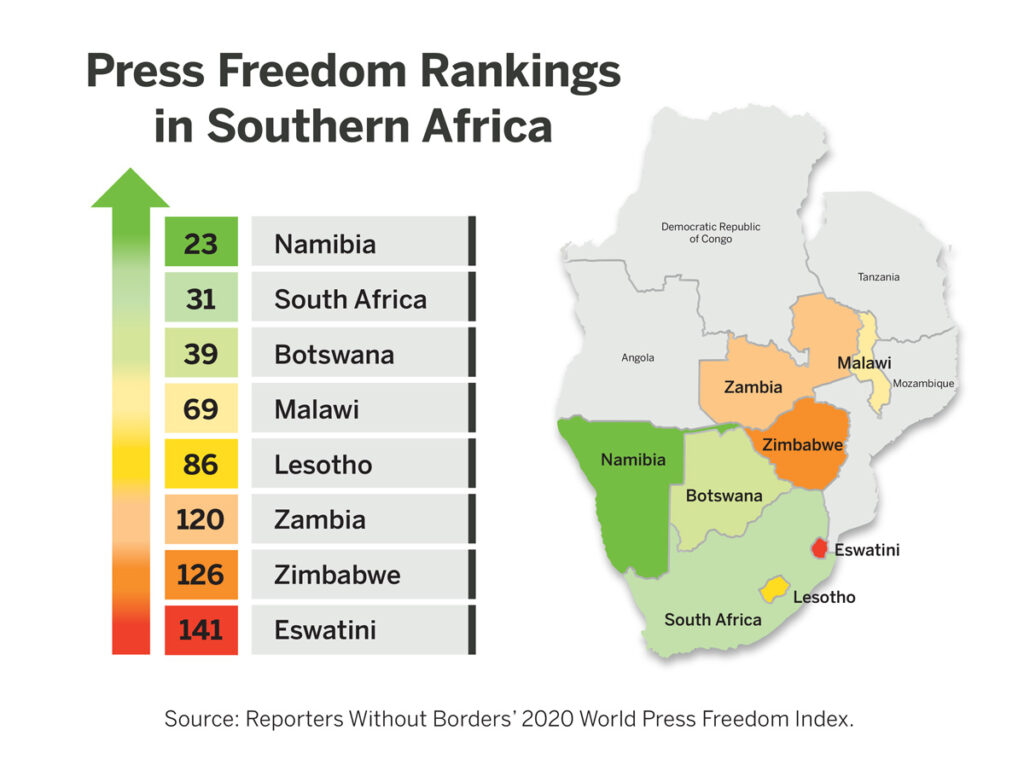

Despite the ongoing challenges to media independence and freedom in the Southern African region, and on the continent more broadly, there are a few notable success stories, such as Namibia and South Africa. Ranking 23rd and 31st, respectively, on the World Press Freedom Index,7 these two countries lead the way in the Southern African region. Both countries have strong constitutional guarantees in place that are defended by the courts, high professional standards, a robust self-regulatory system, and legal frameworks supporting independent media. Nevertheless, threats to and intimidation of journalists remain a concern, and the sustainability of smaller, independent media is constantly under pressure.

The Southern African region also includes several countries where independent media are weak and where media freedom is frequently under attack.8 These include Eswatini, Zimbabwe, and Zambia. In these countries, there is little to no media freedom, and journalists are often persecuted, harassed, imprisoned, and attacked. Independent media operate under repressive legislation and the threat of shutdowns if they report critically. Whereas constitutional guarantees safeguard the work of journalists in countries like South Africa and Namibia, the judicial systems in these more repressive countries often do the opposite by actively undermining constitutional and legal frameworks for independent, critical journalism.

Threats to press freedom in the region also extend beyond physical attacks and imprisonment of journalists to online harassment and trolling, as well as more subtle forms of media manipulation like media capture by state agencies9 and the rising threat of disinformation on the continent.10 The ease and speed with which disinformation can spread in the digital environment, combined with underdeveloped policies to shape a coherent response, make independent media in Africa more vulnerable than ever to actors seeking to undermine their democratic function.

The history of regional cooperation for media reform in Southern Africa

One of the most influential media organizations in the region historically was the Media Institute of Southern Africa. MISA emerged from the 1991 Windhoek Declaration and advocated for media freedoms through a robust regional network. Established in 1994 in Namibia, MISA was envisaged as a regional program with national chapters in 11 Southern African countries. Although MISA’s regional office collapsed11 several years ago, it continues to operate nominally as an umbrella organization, but without staff or resources. There are a few country chapters that are still functional, but they operate autonomously, working together through a loosely organized participatory governance structure. Funding for programs was centralized in the regional office, which used to provide support for in-country chapters until its closure.

Though MISA’s influence has waned over the years, the organization’s strength was its ability to convene stakeholders around issues such as access to information, transformation of public service broadcasters, and campaigns for community radio. MISA also collaborated with other organizations in the region. With no MISA chapter in South Africa, the South African National Editors’ Forum has, on occasion, been asked to represent South African interests at MISA events, and has worked with MISA’s Zimbabwe chapter and the Media Alliance of Zimbabwe on media and election concerns in the region. MISA was involved in initiating a number of successful campaigns, including setting up the African Platform for Access to Information. While MISA and SAEF continue to have a working relationship where they share information, submit jointly to regional bodies, and collaborate on briefings and training opportunities, MISA’s role as a convening body for regional stakeholders has diminished considerably since the closure of the regional office.

Though MISA’s influence has waned over the years, the organization’s strength was its ability to convene stakeholders around issues such as access to information, transformation of public service broadcasters, and campaigns for community radio. MISA also collaborated with other organizations in the region. With no MISA chapter in South Africa, the South African National Editors’ Forum has, on occasion, been asked to represent South African interests at MISA events, and has worked with MISA’s Zimbabwe chapter and the Media Alliance of Zimbabwe on media and election concerns in the region. MISA was involved in initiating a number of successful campaigns, including setting up the African Platform for Access to Information. While MISA and SAEF continue to have a working relationship where they share information, submit jointly to regional bodies, and collaborate on briefings and training opportunities, MISA’s role as a convening body for regional stakeholders has diminished considerably since the closure of the regional office.

Over the years, a gradual professionalization and bureaucratization set in, resulting in competing interests between the regional office and the country chapters. The way that financial resources were distributed among chapters was perceived as nontransparent and politicized, creating power imbalances and resource inequity among countries. As a consequence, some regional chapters became larger and more influential than the regional office overseeing them. Competition among chapters for resources led to internal tensions, unequal capacities, and fragmentation. While some chapters like those in Zimbabwe, Zambia, and Malawi were strong enough to survive independently, others were dependent on the central basket of donor funding. MISA partner organizations experienced this fragmentation and resource inequity as an impediment to sustainable regional collaboration, straining their ability to work with the chapters and hampering effective communication.

Since the closure of the MISA regional office in Namibia, the Zimbabwe and Malawi chapters are the only ones that still have a working relationship with other organizations in the region. However, neither of them has successfully taken on the primary role of the original regional office—connecting Southern African organizations with wider continental and international platforms. This has led to the weakening of solidarity across the region.

The continent-wide organization The African Editors’ Forum (TAEF) and its Southern African regional body, SAEF, are further examples of regional entities that work to strengthen media freedom, independence, and pluralism across borders. Founded in 2003, these bodies were established around the time of the launches of the New Partnership for Africa’s Development in 2001 and the African Union in 2002, when there was clearly continent-wide interest in collaborating to tackle cross-border governance and development issues. Both TAEF and SAEF are therefore closely linked to a renewed commitment to democracy and development on the continent. These regional networks of journalists seek to provide further pathways to achieving the broader goals of democracy in the region by highlighting concerns about the persistent harassment, attacks, and imprisonment of journalists as well as engaging with broader issues such as self-regulation, journalistic ethics, and training.

The continent-wide organization The African Editors’ Forum (TAEF) and its Southern African regional body, SAEF, are further examples of regional entities that work to strengthen media freedom, independence, and pluralism across borders. Founded in 2003, these bodies were established around the time of the launches of the New Partnership for Africa’s Development in 2001 and the African Union in 2002, when there was clearly continent-wide interest in collaborating to tackle cross-border governance and development issues. Both TAEF and SAEF are therefore closely linked to a renewed commitment to democracy and development on the continent. These regional networks of journalists seek to provide further pathways to achieving the broader goals of democracy in the region by highlighting concerns about the persistent harassment, attacks, and imprisonment of journalists as well as engaging with broader issues such as self-regulation, journalistic ethics, and training.

A Desire for Ongoing Regional Collaboration

Despite these efforts, there remains the sense among stakeholders that the void left by MISA’s fragmentation needs to be filled. As such, there have been several recent meetings and consultations that have aimed to reinvigorate regional cooperation. Meetings in Durban, Windhoek, Johannesburg, and Maseru have brought together journalists, activists, funders, and civil society actors to discuss challenges to independent media and freedom of expression in Southern Africa and identify plans and priority areas to jointly address them. The outcomes of these regional meetings demonstrate that actors in the region see the immense benefits of regional cooperation,12 value the strength and solidarity that a network could offer,13 and are committed to multistakeholder, cross-border efforts to build supportive institutions for independent media.

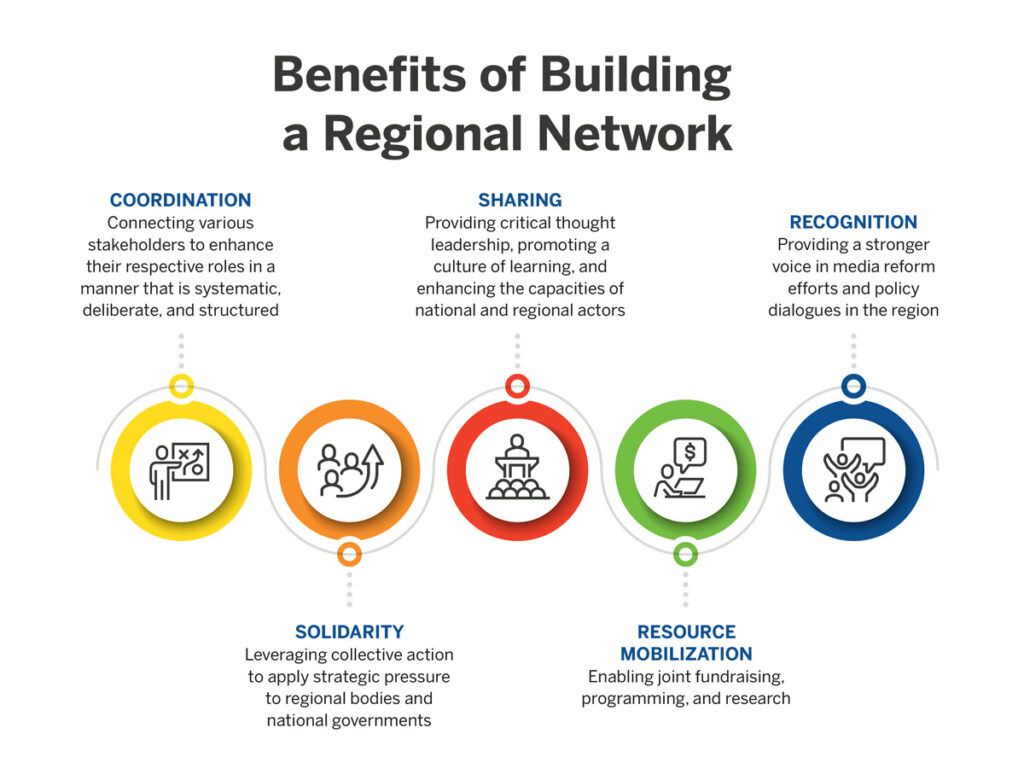

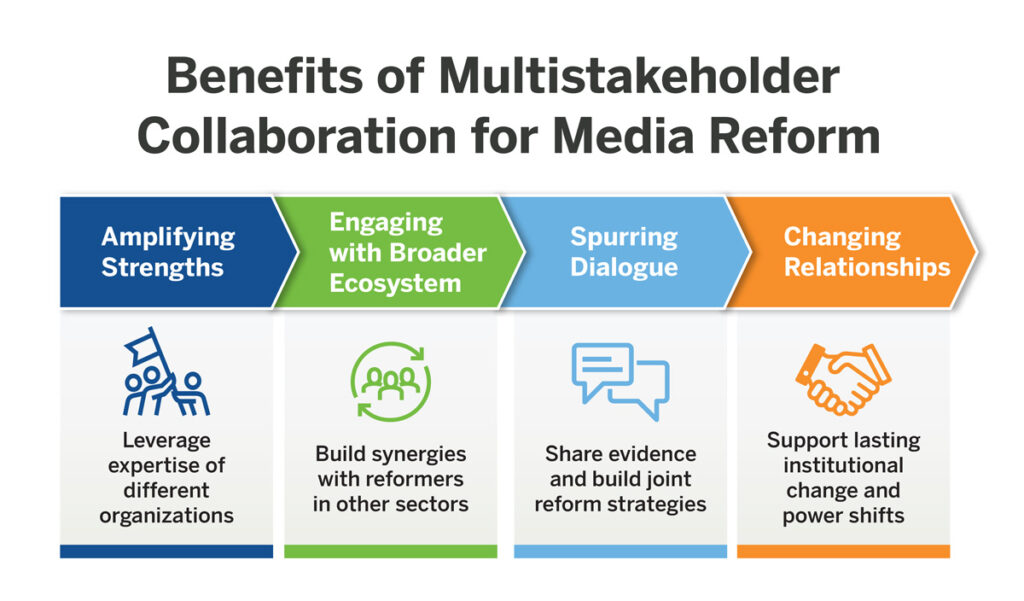

In these prior discussions,14 there was broad consensus that multistakeholder networks of non-state actors working with governments, politicians, regional and international organizations, regulators, and law- and policymakers can play an important role in helping to build a supportive environment for independent media to thrive. However, questions related to precisely what format this network should take, how it should be sustained, and who should take the lead in its implementation remained. Drawing from the deliberations that previously took place, numerous potential benefits of building and sustaining a network were noted.

These priority areas are linked in various ways. For instance, while collaborations among media organizations, donor agencies, and civil society stakeholders can offer support and solidarity in the face of threats to media independence or attacks on journalists, the resilience of these media also depend on their ongoing economic viability. Even in the countries with the most supportive enabling environments, independent media in the region work under conditions of economic precarity. A coalition of media organizations, funders, and civil society organizations could offer spaces to share examples of good practice, nurture innovation, and facilitate access to funding. The sustainability of the media sector and the ability of journalists to do their work without fear or favor are therefore intrinsically linked. Further, legal reforms to end impunity in the region—another priority area—is also contingent on the economic viability of independent media organizations. Sustainability of the media is, in turn, linked to support for independent and public media more generally.

Given digital media’s growth and increasing importance, it is inextricably linked to the other priority areas. For this reason, an overarching imperative for any regional coalition of stakeholders would be to promote and amplify African voices in global debates on digital rights and internet governance.

Declaration of Principles on Freedom of Expression and Access to Information in Africa

An important development in this area has been the recent (2019) adoption of the Declaration of Principles on Freedom of Expression and Access to Information in Africa (DOP) by the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights. The DOP affirms principles for anchoring the rights to freedom of expression and access to information in wider guarantees of individuals’ rights to express and disseminate information in the digital media environment.

Challenges Encountered in Harnessing Momentum for Effective Regional Cooperation

Identifying ‘lead’ organizations that can move the priorities forward

While there are many Southern African organizations and coalitions already working to advance their priorities on discrete issues, none have yet emerged as a clear leading force for a sustained regional coalition-building effort. Various organizations participated in previous meetings, ranging from government actors that co-regulate with media industry representatives (e.g., the Media Council of Kenya) and trade unions (e.g., the National Union of Cameroonian Journalists), to researchers (e.g., the Collaboration on International ICT Policy in East and Southern Africa) and media owners and operators (e.g., the African Media Initiative).

At various points in these deliberations and efforts, different organizations have played a leadership role. The Namibia Media Trust and TAEF took the lead in organizing some of these meetings, supported by donor organizations. Based on some of the outcomes and recommendations emerging from the meetings, the Media Alliance of Zimbabwe began engaging regional organizations such as the SADC and the SADC Parliamentary Forum on issues of media freedom and access to information. These discussions are significant, as historically it has been very difficult for media advocates in the region to effectively engage the SADC. However, it not yet clear which organization could take overall responsibility for establishing and maintaining a regional network, or whether a single organization should in fact be responsible.

Moving from research to policy to action

Several challenges were encountered after these convenings in moving forward a cohesive agenda and maintaining momentum for collaboration. A lack of clear goals, top-down hierarchies, and internal organizational politics thwarted attempts to build and sustain regional coalitions for media reform and media sector development in Southern Africa. Successful examples of regional collaboration demonstrate that success depends, in part, on identifying a clear and limited set of objectives and focused goals.

Previous experience with MISA pointed to the importance of broader sectoral engagement. Advancing identified priorities requires broader consultation and participation beyond media organizations and related stakeholders to include political actors, civil society organizations, faith-based communities, and citizens and citizen organizations such as social justice activists, women’s groups, and youth groups. Collaboration among researchers, policy think tanks, journalists, and human rights organizations is also necessary to ensure research has an impact on policymaking and can result in effective action.

The Way Forward

Leveraging the momentum of these prior discussions, this consultative research project aimed to help actors overcome the roadblocks encountered in sustaining ongoing regional cooperation in recent years and identify what needs to be done to chart a path forward.

The consultative process clearly revealed that there remains significant momentum for greater regional collaboration to support media development and media policy development efforts in Southern Africa. While there are ongoing challenges in articulating a shared vision and operational plan for such a network, the research suggests that there are new and emerging opportunities for such a coalition to be formed and sustained. Although some divergent opinions remain, there is a consensus emerging about what the future might hold for a regional network to bolster independent media in Southern Africa.

Stakeholders in countries across Southern Africa agree that a regional network or coalition could provide Southern African organizations with a stronger voice and a larger regional presence than they currently have. Such a platform would serve to amplify the collective efforts of different groups by fostering greater cooperation with civil society. Such coalitions can help organizations better mobilize against repression in their own countries, facilitate the use of international legal instruments and mechanisms for protection, and augment advocacy work. A coalition or network could break down the silos that currently constrain many organizations and, critically, make it more difficult for governments to ignore or dismiss their efforts.

Many participants also expressed the value of an “African-led” coalition, headed by African organizations and driven by the ideas of local stakeholders,15 that would have greater legitimacy and be more in tune with local needs than externally organized coalitions.

Ongoing challenges and conflicts

Despite the clear potential and enthusiasm for a new regional network to take root in Southern Africa, research participants raised a number of ongoing challenges and debates that have stymied efforts for more formal cooperation. Previous attempts to build networks or coalitions among stakeholders in the region have often dwindled away after initial enthusiasm. As actors have gone from ideation to implementation, they have experienced several roadblocks discussed below in more detail: financial and logistical challenges, ongoing operational questions and disagreements about network organization, unclear leverage points with regional/international bodies, and lack of clarity on approaches and goals.

- Financial and logistical challenges

Uncertainty about the sustainability of independent media outlets and support organizations is a widespread concern in the region. Accessing funding, distributing funding equitably among partners, and deciding on the appropriate funding approach challenged previous collaboration efforts and created conflicts and tensions. When funding agreements are not spelled out clearly, joint fundraising efforts could result in competition or friction among stakeholders. Careful consideration of how funding will be provided and under what terms is critically important to help mitigate the tensions, unhealthy competition, and disagreements that thwarted prior networks.

Uncertainty about the sustainability of independent media outlets and support organizations is a widespread concern in the region. Accessing funding, distributing funding equitably among partners, and deciding on the appropriate funding approach challenged previous collaboration efforts and created conflicts and tensions. When funding agreements are not spelled out clearly, joint fundraising efforts could result in competition or friction among stakeholders. Careful consideration of how funding will be provided and under what terms is critically important to help mitigate the tensions, unhealthy competition, and disagreements that thwarted prior networks.

Research participants repeatedly stressed the need for better donor funding mechanisms to support processes of network building and maintenance. Participants highlighted that funders do not collaborate with one another enough and with organizations on the ground to achieve shared goals. Further, funders in the region often pursue their own agendas rather than responding to local demands. Ensuring better communication, coordination, and collaboration among local organizations, international organizations, and funders has to date proven to be a major obstacle for effective network-building. As one research participant said:

“This is a dynamic environment—[. . .] year after year many players disappear, and this is often related to funding. Short-term funding has a negative impact on sustainability. Many organizations live from grant to grant and get caught up in applications and report-writing. This takes a lot of time and energy. Coalition-building will have to be done on a three to five year funding basis in order to meet objectives and be sustainable.”16

The most feasible funding approach is likely one that funds a small, central coordinating body and specific issue-based campaigns led by members with the most experience in the area of focus. International donors that support coordination processes should avoid imposing a preferred secretariat or lead organization.

- Ongoing operational questions and disagreements about network organization

In prior networks, variations in the size, influence, and resources of member organizations introduced hierarchical inequalities, negatively impacting collaboration and consensus-building efforts. Further, the priorities of more influential and capacitated members diverted energy and attention away from the work of individual organizations. Participants agreed that funding for a small secretariat to facilitate coordination among organizations could help avoid competing interests. The network ought to ensure that its strategic goals supersede those of individual organizations, and that it does not merely replicate, substitute, or detract from the important work each one is doing at a national level. To ensure sustainability, unnecessary bureaucratization ought to be avoided.

Another challenge in network organization expressed by participants was disagreement over its scope. While there was a strong argument in favor of a small, nonhierarchical secretariat leading the way, most stakeholders envisioned it to function on a subregional basis, while others imagined it to be most successful as a continent-wide endeavor. Participants highlighted that a small, informal structure could help prevent unnecessary bureaucratization with the associated overhead costs and duplication of efforts.

A challenge experienced previously by MISA was that although several of its campaigns were highly successful, it could have benefitted from broader sectoral engagement beyond the media and media freedom community. While primary stakeholders of a regional network would be media sector actors who have engaged in previous network-building efforts (media organizations, civil society actors, and funders), research participants stressed the need for broader representation. Participants suggested that a regional network should include rights-based organizations (e.g., the South African Human Rights Commission), anti-corruption and fact-checking groups (e.g., Media Monitoring Africa, the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab, Code for Africa), trade unions, faith-based groups, professional associations (e.g., bar associations), academics, and conflict resolution experts. Parliamentarians, regulatory authorities, and political parties could also be involved on an ad-hoc basis. In advocating for a more broad-based approach to tackle media sector challenges, participants stressed that additional actors should be involved on a case-by-case basis once particular issues have been identified and based on their particular area of expertise. This ad-hoc nature would help prevent diluting the central media-related aims of the network and the potential capture of the process by political actors.

In the process of coalition-building in general, respondents stressed the importance of structural inclusivity and equality. Supporters, such as donors, need to insist that the network promotes gender equality and representation of minority groups as preconditions for funding, and that network members promote female leadership.

In the process of coalition-building in general, respondents stressed the importance of structural inclusivity and equality. Supporters, such as donors, need to insist that the network promotes gender equality and representation of minority groups as preconditions for funding, and that network members promote female leadership.

Stakeholders repeatedly expressed concern over the potential for hierarchical and administrative redundancy. For coalitions and networks to flourish, they have to overcome the challenge of bureaucratization by emerging organically. A participant pointed to an optimal workflow to overcome this challenge: “Identify an issue, mobilize actors around the issue, make issues local, national, regional, and global. Do not create bureaucracies around advocacy, [instead] ask partners to bring their areas of competence and their resources/capacities [to bear].” For this to function, the participant noted that “Priorities need to be set and people should be less territorial and agree to collaborate to find a common purpose [. . .] the most important two issues [are] understanding the need to collaborate; and understanding that our strength lies in solidarity.”17

- Unclear leverage points with regional/international bodies

Regional stakeholders have historically struggled to engage the SADC due to disagreement and contestation among member states. Founding member states were seen as wielding undue influence, and complaints about undemocratic behavior were dismissed as being formulated under the influence of Western funders. There is also a perception that the SADC is “not the most effective regional body on the continent”18 and does not offer as much support as stronger supranational bodies like the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR).

Participants in prior media sector regional networks were frustrated by the SADC’s lack of progress and response. This has led to the view that it is more worthwhile to focus on working with likeminded continental bodies to influence the ACHPR, whose resolutions, policies, and guidelines are binding on regional bodies such as the SADC.

Despite frustration with engaging the SADC on media freedom and media reform issues, research participants nonetheless recognized its importance to national governments. Because of the SADC’s importance, a transnational coalition would need to engage strong local champions who work for national governments and can effectively collaborate with other member governments to strengthen their engagement with the SADC.

Despite frustration with engaging the SADC on media freedom and media reform issues, research participants nonetheless recognized its importance to national governments. Because of the SADC’s importance, a transnational coalition would need to engage strong local champions who work for national governments and can effectively collaborate with other member governments to strengthen their engagement with the SADC.

Despite the limited success of prior attempts to engage the SADC, much can be learned from the few that did gain traction, such as the campaign to establish the African Platform for Access to Information. These efforts highlight that the engagement of state actors often requires a long-term commitment, with concomitant financial obligations. Given that such campaigns require the endorsement of state actors, it is critical to identify organizations that can work effectively with governments and as champions for a particular cause. Such causes may include the review of model laws, especially in the context of this report, on concerns related to cyber legislation, elections, public service media, and media regulation.

Research partners were unclear about how best to engage with the SADC in practical terms. While there was a general desire expressed to “get SADC’s ear,” participants also recognized that decisions made at the continent-wide African Commission level are not always filtered down to the SADC. For this reason, it may be more productive to take a bottom-up approach—working with the African Commission to develop policies and frameworks that are then leveraged as advocacy tools to approach the SADC and other regional bodies. Participant experiences with the SADC suggest that dialogue often fails to impact decision-making. An attempt to domesticate continental-level principles from the African Commission to a subregional level may be difficult in practice, as some research participants did not believe that the SADC is engaging with civil society in a progressive manner. For this reason, some participants argued that engagement with the SADC needs to be more strategic.

A problem experienced with previous MISA campaigns was that they did not engage broadly enough beyond the media and media freedom community. Organizations working on digital rights were often removed from those working on traditional media issues, such as the safety of journalists and access to information. Consequently, to engage strategically with regional bodies, there is a need for more cross-sectoral collaboration, synergy, and cross-pollination on key issues. As stated by one focus group respondent:

“Even within the [media] community, a number of actors don’t sit at the table [. . .] The work of editors is largely divorced from the work of the journalists. Then that whole sector is divorced from the sector of media development organizations, then further down the line, they are divorced from, let’s say, the actors, or very far removed—from academia.”19

- Lack of clarity on approaches and goals

For a regional network to be effective, it must create consensus. Overcoming divergent priorities among members is a critical condition of a network’s success. Where networking and coalition-building efforts were successful in the past, they developed a common approach to identifying pertinent issues and popularizing these issues through joint campaigns. Research partners pointed to engagements at the ACHPR as examples of effective engagement. For example, respondents cited a successful joint campaign to lobby for the release of journalists arrested in Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Swaziland, and Botswana by leveraging the clout of the African Commission. By identifying and clearly defining a set of objectives, concerted campaigns can be designed, drawing on the expertise of network members. The agenda ought to be set by stakeholders themselves, rather than imposed by donors whose focus may shift, creating instability in their wake.

There was broad consensus among research participants that some kind of “game changer” is needed to strengthen the work and extend the reach of existing media advocacy and support organizations, which often lack the capacity to engage in policy debates. The safety of journalists was a recurring concern in discussions, and participants felt that a regional coalition could help provide safe havens across borders, where threatened journalists could take refuge. Assisting threatened journalists to relocate is a sensitive, secretive, and costly endeavor that requires networks of support and solidarity. Such a coalition would also put organizations in a stronger position to engage with policymakers, whether directly or indirectly, around issues of journalistic safety and impunity.

Following from this, one of the important outcomes of a stronger regional coalition would be the amplification of African voices, not only regionally, but also in global debates. Examples of such global developments include include the Forum on Information & Democracy, which is supporting the International Declaration on Information and Democracy; the Internet Governance Forum; and new research groupings on media sustainability. Promising new initiatives also include the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at the University of Oxford and Reporters Without Borders’ Journalism Trust Initiative. Concerns were expressed that without increased representation from Africa in these international movements, stakeholders on the continent will become even more marginalized in the future. For this reason, some participants suggested that a prospective coalition, while regionally focused, ought to have continental reach.

Best practices to build on

There are several examples of successful collaborations on the continent. These collaborations were successful because they a) were issue-driven, b) involved several stakeholders and were organized around a clear purpose, and c) tapped into windows of opportunity at a regional level. The following are illustrative examples.

- Issue-driven collaboration: The South African National Editors’ Forum (SANEF) and Association for Progressive Communications joined forces to advance advocacy efforts on issues related to digital rights, universal internet access, reform of information legislation, and media sustainability. The collaboration produced a joint issue paper on universal free access to online information in South Africa20 and a formal implementation plan.21

- Multistakeholder collaboration with a common purpose: SANEF spearheaded a successful regional campaign with numerous stakeholders, who came together to promote a common regional ethos on media freedom. Through collaboration among SANEF, SAEF, and MISA, and in consultation with experts and interest groups, advancing the principles of a free press and access to information became a common goal for the SADC and the African Union. The collaboration helped ensure that media freedom was included as part of the African Union’s Africa Peer Review Mechanism—a voluntary governance tool used to encourage countries to adhere to international conventions and standards of good governance.

- Identifying windows of opportunity: The Media Foundation for West Africa’s (MFWA’s) engagement with ECOWAS—the primary intergovernmental body in West Africa—is an example of how a window of opportunity may be seized to forge collaborations among stakeholders with varying levels of influence. Although ECOWAS does not have a regional media policy of its own, it and its member states are signatories to a number of conventions and protocols for supporting independent media, such as the Joint Declaration on Media Independence and Diversity in the Digital Age, adopted in Ghana, in 2018. This demonstrates that countries in West Africa have a shared interest in articulating a vision for pluralistic, independent media in the region22. This, coupled with ECOWAS’ desire to engage more with civil society23, presented a window of opportunity for MFWA to advance regional media development issues at the intergovernmental level. To that end, MFWA has been litigating journalists’ rights cases at the ECOWAS Community Court of Justice, and working with the ECOWAS Commission to reform legislation that limits media freedom.

These precedents for regional collaboration on the continent indicate that where opportunities present themselves, a coordinating mechanism can amplify individual members’ capacities to respond. However, to successfully capitalize on such opportunities advocates need to understand where the leverage points exist and identify clear issues that diverse stakeholders can mobilize around. When working with political actors and institutions, it is important for advocates to plan for the long term, anticipate setbacks, and exercise the flexibility and creativity to change course when needed. As one research participant stressed, “engagement with political actors requires tact, patience, [. . .] serious preparation, and readiness for a protracted process.”24

Recommendations

Three broad recommendations for progressing a regional coalition in Southern Africa emerged through the consultative research process: identify assets and emerging priorities; develop an efficient organizational structure; and engage a wide network of stakeholders and citizens.

- Identify assets and emerging priorities

The first step in the process of setting up a prospective network would be to profile the organizations currently working in the region and identify the unique strengths and contributions that each could make to the network. This would help ensure that roles in the network are distributed in line with the capabilities and expertise of different members and facilitate its organic growth. A small secretariat could lead the way by evaluating stakeholder organizations’ key competencies, assessing what gaps exist, and providing a platform for co-creating small-scale projects and new models for engagement. The Declaration of Principles on Freedom of Expression and Access to Information could be used as an overarching framework to guide and ground this work, as noted by a questionnaire respondent:

“The time has passed for a media focus alone to be sufficient. The focus has to be broader and has to be located within the broad ecosystem of digital rights, open data, and universal access to information. A good framework to use is the new Declaration of Principles on Freedom of Expression and Access to Information [. . .] This declaration brings together all the relevant principles, and there is already [broad] buy-in. This framework is the result of years of campaigning on the whole continent, from the ground-up. So this is an organic document that could be a reference point for the coalition and give it some status.”25

Identifying priority areas for engagement would be one of the first tasks of a coalition. This could involve monitoring key developments in respective member countries, issuing alerts and solidarity statements and positions, and establishing an online monitoring and reporting platform to help raise awareness of threats against—and promote the protection of—journalists, particularly in countries with restrictive press freedoms, or in countries in transition where there is a new opening to advance media reforms.

Using key priority areas such as good governance, poverty alleviation, or the Sustainable Development Goals as strategic points of entry, such a coalition could engage the SADC around issues such as digital rights and access to information, judicial and legal reforms, and sustainability of independent media in the region.

- Develop an efficient organizational structure

Careful thought and consultation ought to be given to the issue of a secretariat or convenor. A secretariat function needs to be held by an organization with sufficient credibility in the region to ensure widespread support. While some research participants suggested that TAEF could play this role, there were questions about its capacity to take on this task. SANEF, the Editors’ Forum of Namibia, and the African Freedom of Expression Exchange were also mentioned as possible convenors. The Association for Progressive Communications was also mentioned since it has an existing strong central secretariat, a good track record of success, and capacity to lead the network in a number of areas, including digital rights and safety of journalists.

Research participants stressed the need for a lean and agile secretariat, rather than one that is overly bureaucratic and centralized. Such a secretariat could identify key issues proactively, and task individuals or organizations with leading campaigns on specific issues based on their assets and areas of expertise. In this way, the core of the coalition could be kept small and manageable while drawing on the strengths and expertise of stakeholders across the region. A coalition would therefore not just exist for the sake of creating a network, but have a clear mandate to represent its stakeholders in larger regional and international forums by drawing on the unique capacities of its members. Through its members, such a coalition could monitor issues in various countries, document them, and then consolidate advocacy at a regional level. Different components of the network could be hosted in different countries, instead of locating all the functions in one country. Such a decentralized structure would help prevent the consolidation of power and resources in the hands of a few organizations.

- Engage a wide network of stakeholders and citizens

The coalition would be most successful if it included a wide range of stakeholders and had the support of citizens in the region. To do this, a regular forum could be hosted with attendees from the coalition and other regional and international stakeholders, including government officials, funders, and academics, to communicate the coalition’s activities to the public and get further input on citizen demands and priorities for the media sector. Regular monitoring and evaluation of coalition activities would be important to ensure accountability and transparency.

The coalition could engage stakeholders and citizens on a continuous basis by providing thought leadership and critical analysis through position papers, conducting media literacy campaigns, and working toward generational renewal by engaging students and young leaders through conferences, internships, seminars, and campus visits.

A multistakeholder approach is key to the success of such regional coalitions. By engaging a range of stakeholders, a regional network could access diverse financial, political, and human capacities that could dramatically enhance its visibility and credibility. This diversity is important for keeping media reform issues on the agenda by tapping into a variety of issue areas with regional and national institutions.

A multistakeholder approach is key to the success of such regional coalitions. By engaging a range of stakeholders, a regional network could access diverse financial, political, and human capacities that could dramatically enhance its visibility and credibility. This diversity is important for keeping media reform issues on the agenda by tapping into a variety of issue areas with regional and national institutions.

Conclusion

This consultative research presents a clear case for the value of a regional coalition to enhance media sector development and reform in Southern Africa. There is wide agreement on the ability for such an approach to enhance the capacities of media in the region, build networks of solidarity and support, and engage policymakers and legislators at the national and regional levels around issues of digital rights, media freedom, protection of journalists, and access to information.

Experience with previous attempts at building and sustaining networks in the region has led stakeholders to believe that a lean, agile, and organic coalition would be more successful than a top-heavy, hierarchical structure. While challenges like coordinating funding opportunities, defining clear logistical and operational mechanisms, and finding the appropriate entry points to engage regional policymaking bodies and governments remain, there are already several examples of successful collaborations in the region and further afield on the continent that can serve as guidance and inspiration for such efforts.

Perhaps most importantly, there was strong enthusiasm and motivation among the participants to work on a regional coalition, and a strong belief in the potential impact of such collaboration on media independence, sustainability, and political accountability in the region. As noted by one questionnaire respondent, “There are enormous opportunities. Africa really is the home not just of innovation, but of possibility. The biggest hurdles are commitment, proper resourcing, and clearly defined project goals.”26

Photo Credit

Banner Photo: ©blickwinkel / Alamy Stock Photo

Footnotes

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, Regional Cooperation among Developing Countries Can Help Accelerate Industrialization and Structural Change (Geneva: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 2007).

- Gilbert Tietaah and Sulemana Braimah, A Regional Approach to Media Development in West Africa: Recommendations from a Consultative Process (Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance, 2019), https://www.cima.ned.org/publication/a-regional-approach-to-media-development-in-west-africa/.

- Herman Wasserman and Nicholas Benequista, Pathways to Media Reform in Sub-Saharan Africa: Reflections from a Regional Consultation (Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance, 2017), https://www.cima.ned.org/publication/pathways-to-media-reform-in-sub-saharan-africa/.

- Southern African Development Community, “History and Treaty,” 2021, https://www.sadc.int/about-sadc/overview/history-and-treaty/.

- Media Institute of Southern Africa, “The 1991 Windhoek Declaration,” 1991, https://misa.org/issues-we-address/the-1991-windhoek-declaration/.

- Kwame Karikare, “African Media Breaks ‘Culture of Silence,’” Africa Renewal 24, no. 2 (2010): 23-25.

- Reporters Without Borders, “World Press Freedom Index,” 2020, https://rsf.org/en/ranking.

- Reporters Without Borders, “RSF Index: Big Changes for Press Freedom in Sub-Saharan Africa,” 2019, https://rsf.org/en/2019-rsf-index-big-changes-press-freedom-sub-saharan-africa.

- Greg Nicolson, “Iqbal Survé’s African News Agency Was Paid R20m by State Security Agency, Claims Sydney Mufamadi,” Daily Maverick, January 26, 2021, https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-01-26-iqbal-surves-african-news-agency-was-paid-r20m-by-state-security-agency-claims-sydney-mufamadi/.

- Dani Madrid-Morales, Herman Wasserman, Gregory Gondwe, Khulekani Ndlovu, Etse Sikanku, Melissa Tully, Emeka Umejei, and Chikezie Uzuegbunam, “Motivations for Sharing Misinformation: A Comparative Study in Six Sub-Saharan African Countries,” International Journal of Communication 15 (2021): 1200-1219.

- Rashweat Mukundu, “Regional networks key to better media freedom in Southern Africa,” International Media Support, October 17, 2019, https://www.mediasupport.org/blogpost/regional-networks-key-to-better-media-freedom-in-southern-africa/

- Wasserman and Benequista, Pathways to Media Reform in Sub-Saharan Africa.

- Nthatuoa Koeshe, “Lesotho Urged to Strengthen Media Bodies,” Lesotho Times, December 10, 2019, https://lestimes.com/lesotho-urged-to-strengthen-media-bodies/.

- Wasserman and Benequista, Pathways to Media Reform in Sub-Saharan Africa.

- Anonymous survey respondent #4, November 16, 2020.

- Author interview with veteran editor, November 26, 2020.

- Anonymous respondent #3, in focus group conducted by author, November 24, 2020.

- Anonymous questionnaire respondent #2, November 2020.

- Anonymous respondent #3, in focus group conducted by author, November 24, 2020.

- Association for Progressive Communications, “Perspectives on Universal Free Access to Online Information in South Africa: Free Public Wi-Fi and Zero-Rated Content,” 2017, https://www.apc.org/en/pubs/perspectives-universal-free-access-online-information-south-africa-free-public-wi-fi-and-zero.

- Media Monitoring Africa, South African National Editors’ Forum, Interactive Advertising Bureau of South Africa, and Association for Progressive Communications, Universal Access to the Internet and Free Public Access in South Africa: A Seven-Point Implementation Plan (Pretoria: Media Monitoring Africa, South African National Editors’ Forum, Interactive Advertising Bureau of South Africa, and Association for Progressive Communications, 2019).

- Tietaah and Braimah, A Regional Approach to Media Development in West Africa: Recommendations from a Consultative Process.

- Ibid.

- Anonymous questionnaire respondent #1, November 16, 2020.

- Author interview with veteran editor, November 26, 2020.

- Anonymous questionnaire respondent #4, November 16, 2020.