Key Findings

An increasing number of governments around the world are forcing internet service providers to slow their services during critical sociopolitical junctures—a practice known as throttling—infringing on citizens’ right to information and freedom of expression. Despite its deleterious impact on media development and foundational rights, throttling remains an often-neglected topic and risks becoming a pervasive, yet hidden, threat to press freedoms, democracy, and human rights.

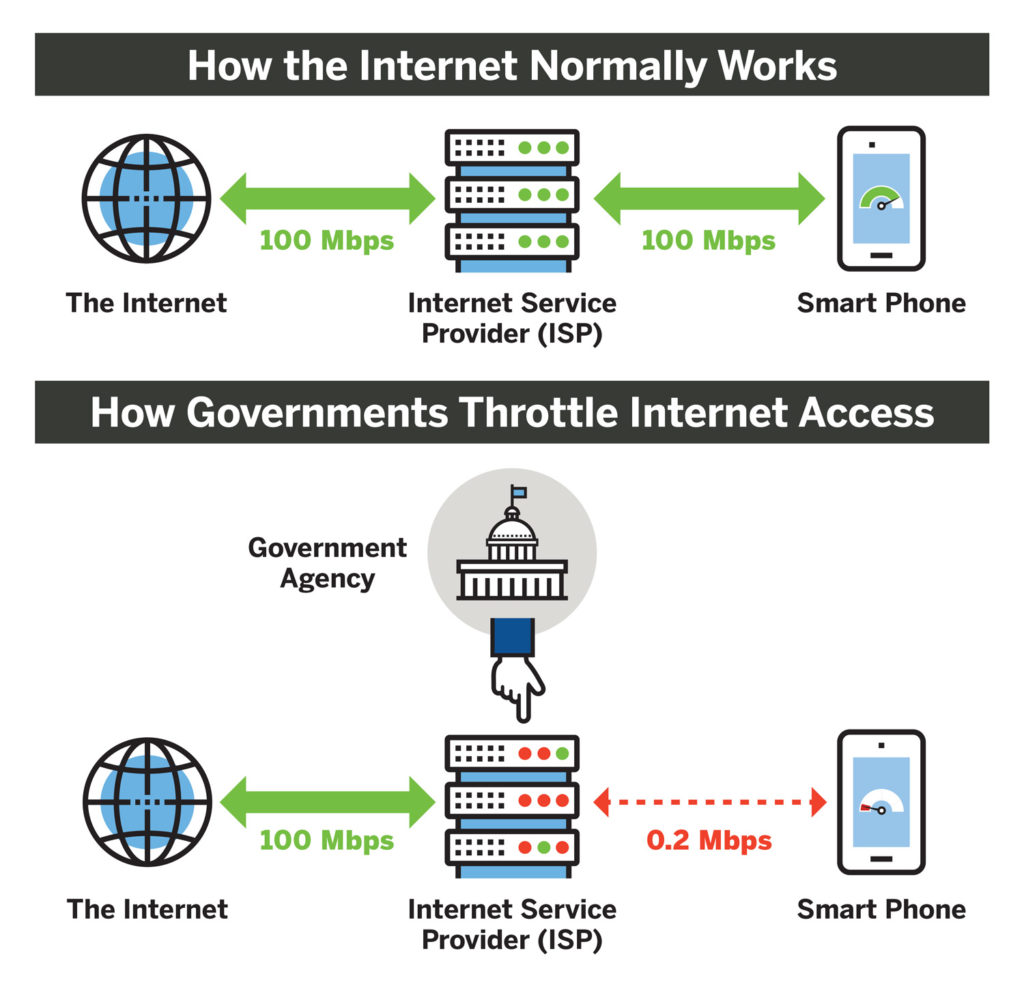

– Throttling refers to the intentional slowing of an internet service by an internet service provider.

– It stifles the free flow of information during critical moments and prevents journalists from providing vital information to citizens abroad and at home.

– Due to its difficulty to detect, throttling shields authorities from public scrutiny.

– Businesses have a duty to be transparent about how and when governments force them to disrupt their services, yet often remain silent on the issue.

Introduction: Internet Throttling Explained

Internet throttling (also known as bandwidth throttling) is the “intentional slowing of an internet service by an internet service provider,” and is rapidly becoming a common method governments are using to stifle the free flow of information during politically significant moments around the world.1

Over the past two years, the digital rights advocacy organization Access Now has documented at least 36 instances of throttling—the vast majority of which have occurred in countries with long histories of violating press freedoms and stifling media development. All of the countries that have implemented the measure mentioned in Access Now’s 2019 internet shutdown report, for example, are in the bottom half of Reporters Without Borders’ World Press Freedom Index.2 Seven of those—China, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, Jordan, Zimbabwe, India, and Bangladesh—are in the bottom third.

Whether a government slows just parts of the web, such as social media platforms, or a country’s entire network, throttling produces similar results as other, more conspicuous, internet restrictions. Namely, it stifles citizens’ attempts to access information, voice their opinions online, and even communicate with their loved ones. As such, throttling poses a significant threat to multiple foundational human rights, including freedom of expression, the right to information, and freedom of assembly. By slowing or stopping communications, it also hurts the economy and impedes scientific, medical, and academic research.

As internet penetration rates continue to rise around the world, and as an ever-increasing section of the world’s population depends on digital media outlets, internet restrictions such as throttling also have clear and, at times, dramatic repercussions for media development and wider democratic processes. Throttling not only limits citizens’ access to information, but also hampers journalism, often at times when it is needed most. It is regularly deployed, for example, as a means of preventing the flow of information during flagrant human rights abuses, making it more difficult for journalists to report accurately.

Throttling is rarely a practice unilaterally carried out by internet service providers (ISPs). Instead, this pernicious type of digital restriction is achieved by governments forcing ISPs to slow parts of their networks. Throttling, as with internet blackouts and social media shutdowns, thus highlights the power that governments have over ISPs in that authorities can, and often do, force providers to act in a way that is diametrically opposed to the ISPs’ own interests.

The independence and transparency of ISPs varies greatly. In Myanmar, for example, Telenor publicly announced in February 2020 that the Ministry of Transport and Communications had directed it to block mobile internet access in several townships in Rakhine and Chin States.3 In most cases, however, ISPs remain silent on the issue. Although forced disruptions, such as throttling, are often associated with state-controlled providers, privately owned companies are also often unable to resist the pressure placed on them by authorities. This is primarily because providers are reliant on authorities for licenses to operate and are therefore relatively helpless to challenge their demands.

Throttling is considerably harder to detect than an internet blackout or social media shutdown. First, it is hard to detect whether a disruption was intentional or accidental—a fact exacerbated in countries with fragile digital infrastructures that are prone to disruption even without government intervention. Second, throttling often impacts only certain platforms, or parts of a platform, such that speeds will appear normal for some users, while for others, the web, or at least parts of the web, will be effectively unusable. Given how difficult it is to document the practice, the true number of countries that have throttled the internet is likely higher than currently known.

The term “internet throttling” has significantly different connotations depending on the context. In the United States, it has become deeply ingrained in discussions of net neutrality and the emergence of a two-tiered internet structure.4 Since the repeal of Obama-era legislation in December 2017, ISPs in the United States have been free to slow the delivery speed of data depending on the website, app, or service being accessed. Proponents have claimed that the lack of regulation would stimulate competition within the telecommunications sector, while many others have criticized its negative impact upon free expression and citizens’ right to information. Countries within the European Union have more robust legislation protecting net neutrality, though it is not without limitations.

Across much of the rest of the world, however, throttling conjures up connotations of censorship, digital authoritarianism, and state control.

Berhan Taye, a senior policy analyst at Access Now and lead of the group’s #KeepItOn coalition, claims that “verifying throttling is hard” and is therefore a more “politically savvy,” though equally problematic, way of restricting citizens’ right to information.5 The number of governments looking to restrict internet access by throttling bandwidth appears set to rise, largely because it is so difficult to detect, which can help shield authorities from public and political scrutiny.

Thanks to the work of the #KeepItOn coalition, the United Nations, and other international human rights advocacy groups, there is now growing pressure on governments to maintain access to the internet and refrain from implementing internet shutdowns.

In 2016, for example, the United Nations Human Rights Council passed a resolution affirming “that the same rights that people have offline must also be protected online” and “condem[ing] unequivocally measures in violation of international human rights law that prevent or disrupt an individual’s ability to seek, receive, or impart information online.”6

Despite the growing awareness of internet restrictions, the majority of this work has focused on internet blackouts and social media shutdowns. In contrast, throttling has remained a relatively obscure and under-researched topic.

This report seeks to shed light on the issue by examining three cases of governments carrying out throttling in three unique contexts: India, Venezuela, and Jordan. These case studies demonstrate that, despite their many differences, in every case, throttling undermines local media development, threatens citizens’ freedom of expression, and stifles individuals’ right to information, often at critical sociopolitical junctures.

India - Jammu and Kashmir

The region of Kashmir, which traverses the borders of Pakistan, India, and China, has been a contested region since before the fall of British colonial occupation. The region’s population have endured protracted conflict, separatist insurgencies, and outbreaks of religious nationalist violence over the past decade, with both Delhi and Islamabad claiming the right to govern the region in full.

On August 5, 2019, the government of India revoked Article 370, a constitutional provision that granted the Indian-controlled territory of Jammu and Kashmir significant autonomy from the central government. According to India’s external affairs minister, Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, the move was “supposed to be a way of dealing with those [past] difficulties.” 7 Pakistan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs condemned the move, describing it as “illegal.”8

As well as revoking Article 370, the Indian government also sent troops to enforce a lockdown and implemented an internet and communication blackout that would quickly become one of the longest and most destructive in history.

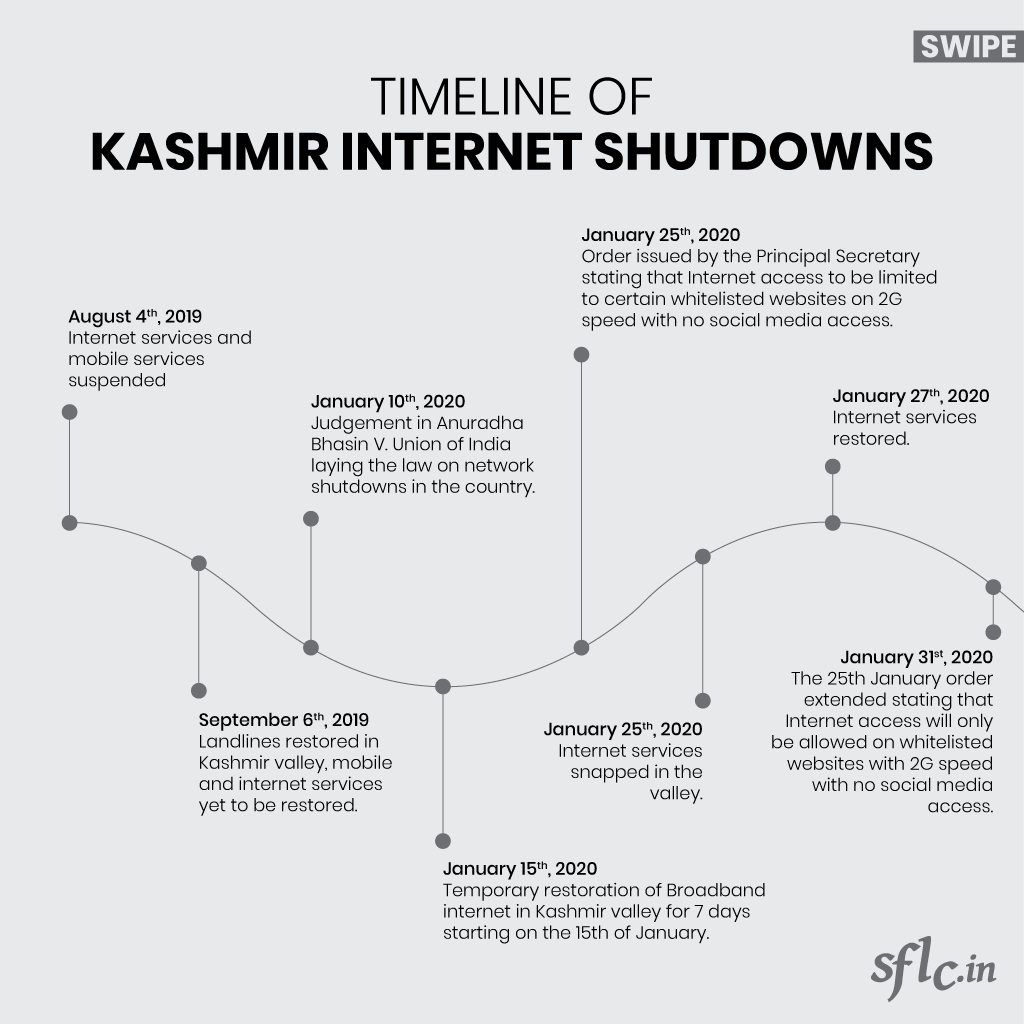

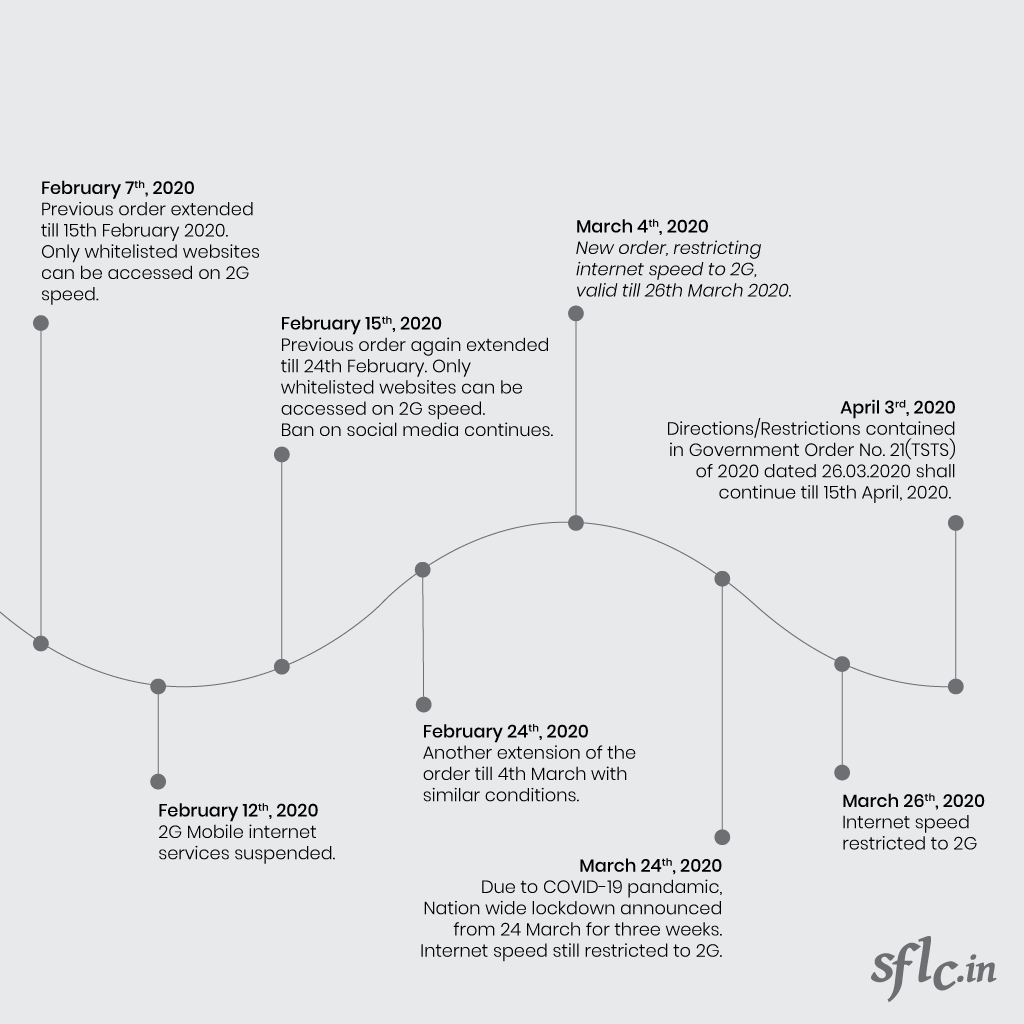

Software Freedom Law Centre (SFLC.in)timeline of internet shutdowns and internet throttling in Jammu and Kashmir. © 2020 by SFLC.in. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Despite the gradual restoration of internet access in the region throughout January 2020, authorities continue to throttle mobile internet speeds with citizens able to access only 2G mobile data connections. Further, when the internet was first restored, citizens could access only “whitelisted” websites selected by the government of Jammu and Kashmir. In its first iteration, this meant citizens could not access many popular social media platforms or digital news outlets. In fact, even many of the whitelisted websites were not accessible. At the time of writing, the ongoing restrictions continued to be challenged in court.

Anuradha Bhasin, executive editor of the Kashmir Times, highlights that, despite many larger media outlets having access to fixed-line internet access, “many freelancers, particularly in the rural areas, rely mostly on mobile internet connectivity, and are unable to operate with regularity” due to the reduced speeds.9 Further, even established outlets are seeing their audience numbers diminish as many readers are dependent on mobile data that is painstakingly slow and practically unusable.

In an open letter, the Software Freedom Law Center argues that the ongoing restrictions prevent the dissemination of vital information, writing, “information cannot be accessed without access to proper internet.”10 It is a point exacerbated by the outbreak of COVID-19. As Avinash Kumar, executive director of Amnesty International India, says, the slow speeds “make it difficult for people to navigate their way through [this] difficult time.”11

Despite the urgent need for access to accurate and reliable information, journalists and medical professionals continue to have their efforts stifled by repressive digital restrictions. As a report by Pranav Dixit for BuzzFeed News highlights: “More than 8 million people who live in Kashmir … are unable to depend on the internet to get reliable information about the coronavirus pandemic.”12

In August 2019, Anuradha Bhasin from the Kashmir Times filed a petition urging authorities “to immediately relax all restrictions on mobile, internet and landline services … in order to enable journalists to practice their profession and exercise their right to report.”13

Although Bhasin’s petition did not lead to immediate relief for the citizens of Jammu and Kashmir, it did prompt some important legal clarifications, including that access to the internet is considered a fundamental right, that it cannot be suspended indefinitely, and that the government must publish all orders of suspension and provide justification for such a decision. Despite these positive developments, there are few signs to suggest that full connectivity will be restored in the coming weeks.

Slowing the speeds of mobile data may not be as drastic or disruptive as the full communication blackout that preceded it. Nevertheless, it has a significant impact on citizens’ ability to access information and express themselves online. Bhasin says, “sometimes one cannot even access Google,” stressing that throttling prevents “people from communicating, accessing social media, or receiving and disseminating information.”

The throttling of mobile data in India has received considerably less media attention than the full communication blackout: “Now no one is speaking about Kashmir still being offline, but technically Kashmir is still offline because there’s nothing you can do with a 2G internet connection.”14

The Indian government claims to have restored access to the internet in a bid to quell domestic and international scrutiny. The inspector general of police in Kashmir, Vijay Kumar, for example, told the Economic Times that “If there is no white or black list with the government’s order, it means every website can be accessed now.”15 What this fails to mention is that with heavily restricted speeds only basic text-only pages are likely to function, and many popular websites will remain inaccessible for the majority of the region’s population.

In a country with rapidly declining press freedoms,16 authorities are now restricting citizens’ ability to access vital information during a global health emergency in the most subtle way possible.

The pernicious nature of throttling is undoubtedly one of its defining features. However, unlike many other countries, India is relatively transparent about the implementation of digital restrictions due to sustained challenges made by civil society organizations. In countries where this transparency does not exist, identifying, monitoring, and fighting against throttling is considerably more difficult.

Venezuela

Following a contested election in 2018, Venezuela has experienced extreme political, social, and economic instability under the influence of an increasingly authoritarian president. Conditions deteriorated further after Juan Guaidó was named interim president by the National Assembly, which culminated in an attempted uprising in April 2019. Hyperinflation has crippled the economy and Nicolás Maduro’s government continues to face allegations of corruption, torture, and gross human rights violations.17

The recent upheaval also had a significant digital dimension. From blocking access to Wikipedia to a suspected state-backed phishing attack on a humanitarian aid website, authorities have deployed a range of technologies in a bid to stamp out discontent and stifle opposition voices.18

Maduro’s increasing authoritarianism and lack of transparency makes monitoring intentional digital restrictions difficult. This is exacerbated by the country’s fragile digital infrastructure. In March 2019, for example, there were multiple power outages that affected the entire country. The impact was stark, with millions being left with no water, food, or telecommunications.19

The latest unintentional disruption was caused on March 5, when internet connectivity fell to 50 percent of ordinary levels for users of state-run internet service provider CANTV due to a fire at the company’s offices in Caracas, according to NetBlocks.20

The fragility of the country’s digital infrastructure is a significant barrier in identifying whether specific digital disruptions were deliberate or unintentional. It is, according to Taye from Access Now, a relatively common theme: “Countries that throttle the internet normally … don’t have the best internet infrastructure.”

Despite this, monitoring groups have been able to verify several intentional disruptions in recent years. According to Access Now, for example, “Following India, Venezuela was a global ‘leader’ for shutdowns, blocking access to social media platforms at least 12 times in 2019.”21

Margaret López, a freelance journalist in Venezuela, stresses that there is a clear correlation between significant political moments and digital disruptions. These have included social media blocks, as well as the intentional slowing of the internet. For instance, when Guaidó took the oath as president-in-charge of the Executive on January 23, 2019, the internet was practically unusable.22

Confirmed: YouTube, Google and other services blocked in #Venezuela as Juan Guaidó speaks live on air about future planshttps://t.co/VZUy259UPb pic.twitter.com/yEgukgjISu

— NetBlocks.org (@netblocks) February 18, 2019

López provides other examples as well: “the use of throttling was also repeated during several days of popular mobilizations in the streets during the years 2014 and 2017. This gives us hints of the intent behind the throttling.” The intentions of such restrictions are indeed increasingly clear. Namely, they represent an attempt to stifle the free flow of information and silence critics during crucial sociopolitical moments.

Unlike in India, these disruptions have most frequently affected social media platforms and have, by and large, been short-lived. On multiple occasions, for example, YouTube and other streaming platforms were blocked for the exact duration of Guaidó’s public speeches.

According to NetBlocks, “Access has typically been restored shortly after the speeches end, with each incident lasting from just 12 minutes to over an hour.”23 Despite being short-lived, however, the restrictions continue to have a deleterious impact on local media development and press freedoms.

“By reducing the bandwidth of the internet connection and blocking access to these social networks from internet providers, the authoritarian government seeks to reduce the amplification of opposition messages,” López said. It has also prevented journalists from covering developments live and providing citizens with up-to-date information during particularly turbulent periods. During protests, this information can be vital, allowing, for instance, citizens to know where outbreaks of violence and police brutality are occurring.

This brief description illustrates that at critical points in the past several years, the Venezuelan regime has looked to digital restrictions as a means of silencing opposition voices and clamping down on independent journalism.

Bandwidth throttling and social media blocks are, of course, only two of many ways the regime has sought to control the flow of information in the country. According to Reporters Without Borders, “Nicolás Maduro persists in trying to silence independent media outlets and keep news coverage under constant control.”24

However, throttling and other digital restrictions have continued to play their part and are becoming increasingly acute. According to Freedom House’s Freedom on the Net 2019 report: “Venezuela’s internet freedom continued to deteriorate [in 2019] as internet connectivity became more precarious and service providers intermittently blocked major conduits for independent news and information.”25

Unlike in India, throttling and social media restrictions in Venezuela are targeted, mostly short-term, and implemented with little transparency. With the combination of a fragile digital infrastructure, minimal transparency, and the detrimental nature of throttling, authorities have been able to silence critical voices, maintain control of the media, and restrict citizens’ right to information. Additionally, this combination of factors means that comprehensively documenting the extent to which the authorities have limited access to the internet in Venezuela remains unlikely.

Jordan

Throughout May and June 2018, peaceful protests erupted across Jordan in response to new austerity taxes and a rise in fuel and electricity prices. In December of the same year, large protests once again broke out following a perceived lack of progress and the introduction of a controversial fiscal reform bill. The protests occurred weekly and continued into the new year.

According to a joint report published by the Jordan Open Source Association and the Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI), “amid the protests, locals reported that they were unable to view live-streaming from Facebook.” As the report makes clear, locals could access the livestreaming feature as normal when protests were not occurring.

Although it was initially thought that citizens could not access the service because the network was overloaded, the technical report published in June 2019 showed instead that Jordanian authorities intentionally interfered with the platform. Unlike the disruptions documented in India and Venezuela, throttling in Jordan impacted only one function of a particular web service, rather than the entire network or platform. This was achieved by disrupting the cache servers in the country and appeared to impact all local ISPs similarly.

Screenshot of error that would occur when Jordanian citizens attempt to livestream protests via Facebook. © 2020 by Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Raya Sharbain, project coordinator at Jordan Open Source Association, explains that by throttling the livestreaming feature of Facebook, authorities prevented people from “learning about the protests in the first place, knowing where protests [were] occurring, seeing how many people [were] participating, and feeling encouraged to join in.”26

Importantly, Sharbain also suggested that throttling had been used to prevent citizens from documenting and disseminating footage of violent police behavior. “All in all, it’s used to stifle public gatherings and discourage freedom of association,” Sharbain said.

Berhan Taye also shared this concern, stating, “If you’re out on the street during a protest and you’re trying to film and livestream excessive use of violence by law enforcement agencies, that would not be possible” while the connection was throttled.

Although the videos could circulate after the protests, livestreaming services provide an important avenue for the immediate dissemination of information, which can prove a significant means of galvanizing popular opposition movements. This is particularly significant in Jordan, where the use of Facebook’s livestreaming service is widespread. As Sharbain highlights, “Jordanians tend to use Facebook Live a lot during protests and authorities usually tend to target the most used platform with the potential to have the biggest impact on protest participation.”

Authorities could have blocked access to Facebook in its entirety, rather than throttle just the livestreaming feature. However, this would have risked provoking greater discontent and could have resulted in greater participation in the protests.

As was seen in Lebanon in late 2019, digital restrictions implemented at times of popular discontent can exacerbate underlying social and economic unrest.27 Instead, throttling “gives users the impression that the platform is malfunctioning in some parts” and prevents, or at least slows, people “denouncing a censorship attempt,” Sharbain said.

Conclusion: Calling out a Pernicious Threat to Media Development

In each of the three cases above, bandwidth throttling has been used as a covert means of controlling the flow of information during significant sociopolitical junctures. Despite their differences, in each case the impact is relatively similar—the practice disrupts journalists’ attempts to provide vital information, enabling authorities to maintain control over the public narrative.

In each of the three cases above, bandwidth throttling has been used as a covert means of controlling the flow of information during significant sociopolitical junctures. Despite their differences, in each case the impact is relatively similar—the practice disrupts journalists’ attempts to provide vital information, enabling authorities to maintain control over the public narrative.

It impacts those without access to reliable alternatives the hardest and, when deployed in conjunction with other forms of digital repression and censorship, stifles freedom of expression and broader media development efforts.

As the cases exemplify, throttling is used as a means of quelling protests, silencing opposition voices, and preventing journalists from covering developments as they happen, often during flagrant human rights abuses. As Berhan Taye stresses, often “the reason the government is not allowing livestreaming is because they know that their law enforcement agencies, the military, the police, the paramilitary are going around and abusing human beings.”28

Yet all too often throttling goes unnoticed. Importantly, the insidious nature of throttling shields authorities from domestic and international condemnation while retaining their control over the flow of information. Whereas internet blackouts and social media shutdowns have faced growing criticism in recent years, throttling is frequently neglected in discussions of internet freedoms.

Going forward, civil society, business, and academic leaders will have to put more attention on reliably identifying instances of throttling to prevent it from becoming more widespread. Without more public awareness, the risk is that throttling will continue to proliferate, with increasing numbers of citizens in countries throughout the world unable to access information at vital times.

Internet service providers should also follow the United Nations’ Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and look to be more transparent about government interference. Doing so would provide civil society with more accurate information about how frequently and on what grounds these demands are made. More robust protections for ISPs that would enable companies to reject demands from authorities to disrupt their services should also be explored.

Without greater scrutiny, transparency, and action, internet throttling will remain a pervasive hidden threat to media development around the world, and radically undermine the basic tenants of democratic life.

Footnotes

- Berhan Taye and Sage Cheng, “The State of Internet Shutdowns,” Access Now, July 8, 2019, https://www.accessnow.org/the-state-of-internet-shutdowns-in-2018/.

- Reporters Without Borders, “2019 World Press Freedom Index,” April 18, 2019, https://rsf.org/en/ranking.

- Telenor, “Internet Services Restricted in Myanmar Townships (Updated 2 May 2020),” Originally published February 3, 2020, www.telenor.com/internet-services-restricted-in-five-townships-in-myanmar-03-february-2020/.

- Katharine Trendacosta, “Real Net Neutrality Is More than a Ban on Blocking, Throttling, and Paid Prioritization,” Electronic Frontier Foundation, February 7, 2019, https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2019/02/real-net-neutrality-more-ban-blocking-throttling-and-paid-prioritization.

- Berhan Taye, Personal Communication, March 13, 2020.

- United Nations Human Rights Council, The Promotion, Protection and Enjoyment of Human Rights on the Internet (New York: United Nations General Assembly, July 4, 2018), https://ap.ohchr.org/documents/dpage_e.aspx?si=A/HRC/38/L.10/Rev.1.

- The Economic Times, “Kashmir Was in Mess before Aug 5- Jainshankar,” September 2019, 2019, https://www.businesstoday.in/current/economy-politics/jammu-and-kashmir-crisis-pakistan-condemns-india-move-says-will-exercise-all-options-to-counter-illegal-steps/story/370612.html.

- Business Today, Article 370 Revoked – Pakistan Condemns Modi Governments Kashmir Decision, Calls It Illegal, August 5, 2019, https://www.businesstoday.in/current/economy-politics/jammu-and-kashmir-crisis-pakistan-condemns-india-move-says-will-exercise-all-options-to-counter-illegal-steps/story/370612.html.

- Anuradha Bhasin, Personal Communication, March 10, 2020.

- Software Freedom Law Center, India, “Open Letter for Restoration of 4G Internet in Jammu and Kashmir in Wake of COVID-19,” March 31, 2020, https://sflc.in/open-letter-restoration-4g-internet-jammu-and-kashmir-wake-covid19.

- Amnesty International, “Mitigate Risks of Covid-19 for Jammu and Kashmir by Immediately Restoring Full Access to Internet Services,” March 19, 2020, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/03/mitigate-risks-of-covid-19-for-jammu-and-kashmir-by-immediately-restoring-full-access-to-internet-services/.

- Pranav Dixit, “8 Million People Can’t Get News about the Coronavirus because Their Government Is Slowing Down the Internet,” BuzzFeed News, March 18, 2020, https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/pranavdixit/coronavirus-india-kashmir-internet.

- LiveLaw News Network, “Kashmir Times Editor Moves SC against Curbs on Media Freedom in the Valley,” August 10, 2019, https://www.livelaw.in/top-stories/kashmir-times-editor-moves-sc-against-curbs-media-freedom-in-valley-147099.

- Berhan Taye, Personal Communication, March 13, 2020.

- Hakeem Irfan Rashid, “Ban on Social Media Lifted in J-K, Access to Internet Services on 2G to Continue Till Mar 17,” Economic Times India, March 5, 2020, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/ban-on-social-media-lifted-in-j-k-access-to-internet-services-on-2g-to-continue-till-mar-17/articleshow/74477608.cms?from=mdr.

- Reporters Without Borders, “2019 World Press Freedom Index – A Cycle of Fear,” April 18, 2019, https://rsf.org/en/2019-world-press-freedom-index-cycle-fear.

- Tom Phillips, “Venezuela: UN Report Accuses Maduro of ‘Gross Violations’ against Dissenters,” The Guardian, July 4, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jul/04/venezuela-un-report-nicolas-maduro-violations-against-dissenters.

- Samuel Woodhams, “Maduro’s Hidden Censorship Apparatus,” Global Americans, March 14, 2019, https://theglobalamericans.org/2019/03/maduros-hidden-censorship-apparatus/.

- BBC News, “Venezuela Power Cuts: Blackouts Continue as Protests Loom,” March 9, 2019, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-47504722.

- NetBlocks, Twitter post, April 6, 2020, https://twitter.com/netblocks/status/1246973747682324481.

- Berhan Taye, Targeted, Cut Off, and Left in the Dark: The #KeepItOn Report on Internet Shutdowns in 2019 (New York: Access Now, February 21, 2020), https://www.accessnow.org/cms/assets/uploads/2020/02/KeepItOn-2019-report-1.pdf.

- Margaret López, Personal Communication, April 1, 2020.

- NetBlocks, “YouTube and Google Services Restricted in Venezuela as Guaidó Speaks,” February 18, 2019, https://netblocks.org/reports/youtube-and-google-services-restricted-in-venezuela-as-guaido-speaks-v7yN4EAq.

- Reporters Without Borders, “Venezuela,” Accessed April 18, https://rsf.org/en/venezuela.

- Freedom House, “Venezuela: Freedom on the Net 2019,” November 4, 2019, https://freedomhouse.org/country/venezuela/freedom-net/2019.

- Raya Sharbain, Personal Communication, March 30, 2020.

- BBC News, “Lebanon Protests: How WhatsApp Tax Anger Revealed a Much Deeper Crisis,” November 7, 2019, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-50293636.

- Berhan Taye, Personal Communication, March 13, 2020.