Introduction

Following the ouster of longtime President Omar al-Bashir in 2019, Sudanese journalists enjoyed freedoms many had never experienced in their lifetimes.

Systematic censorship of news reports stopped and raids on media houses by the feared National Intelligence and Security Services came to a halt. The arrest and detention of journalists, once commonplace, became rare, and the harassment of online activists by pro-government trolls eased. The redlines that barred journalists from reporting on topics sensitive to the government were rolled back; a former journalist, imprisoned under al-Bashir, even became the new minister of culture and information.

They enjoyed those freedoms until October 2021, when Sudan’s military seized power from its civilian partners in the country’s transitional government. Anti-coup protests were met with a deadly response from soldiers, and the government cut internet access and detained journalists along with civilian leaders of the transitional government. Mechanisms of control over media were restored. Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok was briefly detained by the military and later released, only to resign his position in January 2022 after an unsuccessful effort to restore civilian rule.

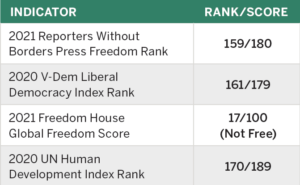

This report, part of the Center for International Media Assistance’s “Media Reform amid Political Upheaval” series, reviews Sudan’s media climate and examines the role of Sudan’s government, media, foreign donors, and international media assistance actors in attempting to foster change in a country that is among the most inhospitable environments in the world for independent media.

Though Sudan’s immediate democratic outlook remains grim, continued investments in the media sector will be essential for the country’s return to civilian rule. Interviews with 39 journalists, government officials, donor representatives, and other stakeholders point to how efforts can be made to support the media sector even as governance reforms have stalled. Independent news outlets need support to grow and professionalize. Civil society organizations in Sudan would benefit from greater capacity to strengthen the media sector. International donors providing assistance on poverty alleviation, health, and other aspects of development can continue to insist on a free and open media sector as an essential condition for cooperation. In that regard, Sudan is an instructive case study for media support in countries undergoing a partial political opening.

Background

Sudan today is greatly shaped by the 30-year rule of al-Bashir, who took power in a 1989 coup. Al-Bashir’s reign was characterized by repression, corruption, and episodic efforts to impose Islamic law. For much of his tenure, the government was on a war footing, facing major internal rebellions in the South (until the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement that paved the way for South Sudan’s independence) and in Darfur from 2003. These wars combined have claimed approximately 700,000 lives to date. The government also fought smaller internal conflicts in other parts of the country. Despite having significant oil reserves, in 2020 the country ranked 170th out of 189 nations on the United Nations (UN) Human Development Index, a broad measure of education, health, and income.

Al-Bashir took a classic authoritarian approach to media. Before the 2019 revolution, the government and ruling National Congress Party controlled much of the press. The independent media sector was decimated during al-Bashir’s reign, with journalists critical of the government facing attacks and imprisonment or fleeing into exile. Many simply stopped writing about sensitive topics in the face of constant harassment by government security forces. “Journalists [would] find themselves in court every single day and this happened to so many people that at some point you just start self-censoring because you are so exhausted,” said one Sudanese freelance journalist.1

Al-Bashir took a classic authoritarian approach to media. Before the 2019 revolution, the government and ruling National Congress Party controlled much of the press. The independent media sector was decimated during al-Bashir’s reign, with journalists critical of the government facing attacks and imprisonment or fleeing into exile. Many simply stopped writing about sensitive topics in the face of constant harassment by government security forces. “Journalists [would] find themselves in court every single day and this happened to so many people that at some point you just start self-censoring because you are so exhausted,” said one Sudanese freelance journalist.1

Online, the government resorted to shutting down the internet during periods of tension and blocking and filtering critical websites. In the wake of the 2011 Arab Spring, the National Intelligence and Security Services also created a Cyber-Jihadist Unit to monitor social media and news sites, harass dissidents and journalists, spread disinformation, and launch cyberattacks against critical webpages.

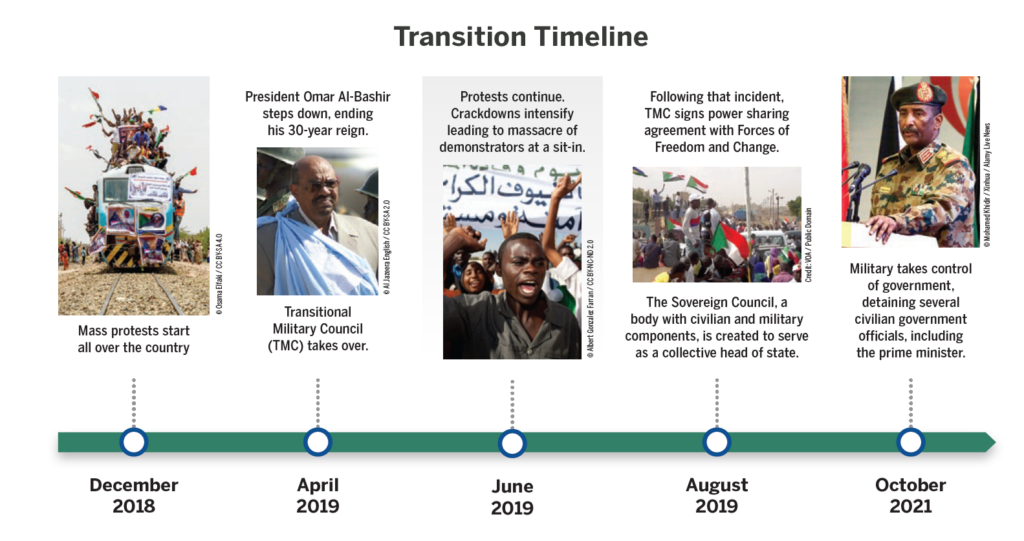

The uprising against al-Bashir began in December 2018, when secondary school students began demonstrating against increases in the price of bread. Aided by social media, the protests spread and soon were led and organized by the Sudanese Professionals Association, an umbrella group that included associations of doctors, lawyers, journalists, and other middle-class professionals, as well as women’s groups, academics, and opposition politicians.

The uprising against al-Bashir began in December 2018, when secondary school students began demonstrating against increases in the price of bread. Aided by social media, the protests spread and soon were led and organized by the Sudanese Professionals Association, an umbrella group that included associations of doctors, lawyers, journalists, and other middle-class professionals, as well as women’s groups, academics, and opposition politicians.

In the face of unrelenting street protests, al-Bashir was ousted by his own military in April 2019. The generals proceeded to set up a transitional military council to rule the country. This failed to satisfy the protestors, and mass demonstrations continued. After an estimated 128 people were killed during a sit-in in June 2019, the military faced international outrage and eventually signed a power-sharing agreement with the Forces of Freedom and Change, a coalition representing the demonstrators. That agreement formed the basis for two years of unstable partnership between the military and a civilian government led by Hamdok.

Sudan’s Media Today

The formation of the transitional government heralded Sudan’s opportunity for democratic change, including media reform. This began from a low baseline. Large portions of the country do not have access to FM radio—much less television, satellite, internet, or print media. As of 2020, the country had just 45 newspapers, 65 radio stations, and 19 television stations. By comparison, Mali—a country with half the population of Sudan—has 227 newspapers, 373 radio stations, and 18 television channels. Most of the outlets are concentrated in Khartoum. As a result, much coverage focuses on the capital as news organizations generally do not have the resources to send correspondents to the countryside.

Sudan’s two state media enterprises, the Sudan News Agency and the Sudanese Radio and Television Corporation, together employ about 2,000 staffers and have a relatively broad audience. However, even after the 2019 uprising, neither agency is seen as editorially independent. State media generally continue to share the “official” view of events without question. Staff at the state broadcaster are poorly paid and equipment is generally run down. Audiences have little trust in the government and, consequently, state news outlets: A recent survey by media development agency Internews found that many Sudanese turn to international news sources to verify information about their own country.

Independent media companies in Sudan face a number of major challenges. Frequent power outages hinder electronic and online media. Rampant inflation, shrinking advertising revenues, corruption, and lockdowns related to the COVID-19 pandemic make turning a profit difficult, as independent media do not receive state subsidies. Due to printing costs, a newspaper is a luxury item, costing as much as six loaves of bread as of mid-2021.

As a result, journalist salaries are low, and many reporters are tempted by bribes. The legacy of government repression, a dismal economic environment, and poor training combine to keep the standard of Sudanese journalism low, according to Sudanese stakeholders interviewed for this report. “Journalists in Sudan haven’t been doing journalism for the past 30 years,” said one Sudanese analyst.2 “I have never read an investigative piece in a Sudanese newspaper, for example. Most of the content in newspapers is very basic and the quality of it is embarrassing.”

The rise of social media greatly increased the communication capacities of ordinary Sudanese, as more than 30 percent of the population now has internet access. The effect of this was clearly demonstrated during the 2019 demonstrations, when the protests and government response were broadcast live to the world by demonstrators. However, the government’s Cyber-Jihadist Unit, which Reporters Without Borders calls a “troll army,” continued to operate even after the revolution and spread false information on social media to undermine the civilian wing of the transitional government.

The split between the military and the civilian branches of the transitional government was a defining feature in the two-year effort to reform Sudan’s media. The civilian government repeatedly stated that media freedom was among the government’s top priorities, an interest demonstrated by Hamdok’s signing of the Global Campaign for Media Freedom pledge during the 2019 UN General Assembly. However, the military, led by Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, clearly mistrusted independent media and sought to reverse efforts to strengthen them almost immediately after the October 2021 coup.

Obstacles to Media Reform

From the start of the people’s revolution in 2019, the groups opposing al-Bashir recognized the importance of media freedom and prioritized it in their negotiations with the military. In August 2019, representatives of the military council and the civilian movement signed a transitional constitution, which included provisions guaranteeing freedom of expression, freedom of the press, and the right to access the internet. This came just weeks after the military announced major reforms to the National Intelligence and Security Services, which had been the previous regime’s major tool for harassing media outlets.

These were important steps and helped reduce censorship and attacks on independent media. However, more systemic reforms to the media climate during the reform window proved problematic. There were many reasons for this.

In part, this was due to the poor condition of Sudan’s civil society. Under al-Bashir, civil society groups were systematically targeted by the regime, which accused them of having links to opposition groups and banned them from conducting work on issues such as human rights. This left them ill-equipped to help lead the reform process.

Another factor was the weakness of the civilian side of the transitional government. Two years after the revolution, the government had yet to establish a legislative body or key transitional commissions that could implement many of the legal and institutional reforms outlined in the transitional constitution and later media reform proposals. Though respected independent journalists were appointed to key positions at the Ministry of Culture and Information, some media stakeholders grew frustrated with the slow pace of change. One Sudanese civil society representative who had joined a government-organized committee on media reform claimed that changes in government personnel stymied advances and that “there is no clear strategy or any progress.”

Further, the military and supporters of the old regime showed no interest in media reform. The army continued to see itself as above criticism and maintained control of the internet, periodically blacking out access. In July 2020, the military appointed a special commissioner to file lawsuits against those who “insult” the military online. Throughout the transitional period, the military often seemed to be making media policy directly at odds with the civilians in government.

Another impediment to change was that supporters of al-Bashir’s former regime maintained control of large segments of the media and continued to receive government advertising revenues. Most of the 18 daily newspapers that covered politics in the country were owned or linked to supporters of al-Bashir’s government, and continue to be so today. Meanwhile, efforts by the civilian government to strip al-Bashir supporters of control of media assets were met with significant pushback, and raised concerns that the reformists in government were themselves infringing on free expression. Sudan’s print media regulator, the National Press and Publications Council, a legacy of the al-Bashir government, continues to operate.

Additionally, there is little evidence of broad public support for media reform. A recent public opinion survey by ORB International3 found that most Sudanese surveyed were focused on satisfying basic needs such as food, jobs, security, education, and access to public services like electricity and healthcare. While the survey found support for the greater freedom of expression the transitional government enabled, particularly on social media, this did not necessarily translate into support for a reformed and independent media sector.

A final obstacle to reform was that some longstanding practices in newsrooms proved difficult to dislodge after 30 years of repression and enforcement of conservative Islamic codes. Female journalists hold few management positions in media and are more often targets of harassment and violence. Self-censorship continues to be ingrained at most news outlets. The state’s control over the advertising market incentivizes many journalists to toe the government line in their reporting.

Searching for Direction – International Media Assistance in Sudan

Sudan is historically a large recipient of international aid despite the al-Bashir regime’s often hostile relationship with the United States and European powers. However, prior to the 2018–19 uprising, aid for governance and media development was limited. Still, a small number of international agencies worked in media development in the country, primarily doing training and working “below the radar” of the Sudanese government. This group included Internews, Free Press Unlimited, and the Thomson Foundation.

After the uprising, one of the earliest and most significant media assistance projects undertaken by the international community was an effort by UNESCO to create a roadmap for media reform that would outline needed changes to the sector. With funding from the United Kingdom, the UN agency held a series of meetings with journalists and media experts in cooperation with Sudan’s information ministry to gather input on the way forward.

In February 2020, it released its recommendations, which called on the government to tackle 28 comprehensive action items. Among them were legal changes: replacing a 2009 press law that permitted prepublication censorship, passing a new broadcasting law to allow for the independent regulation of radio, and enacting regulations to create transparency in media ownership and prevent excessive media concentration. The proposal also called for institution building and restructuring: the overhaul of state-owned media to guarantee editorial independence, the creation of an independent agency to oversee the distribution of government advertising, and the development of a government office to oversee freedom of information requests. Ambitiously, it called for most of these reforms to be completed by the end of 2022.4

By mid-2021, it was still not clear how the roadmap would be implemented and which government entities would be responsible for carrying it out. Even before the October 2021 coup, personnel changes at both Sudan’s Ministry of Culture and Information and within UNESCO raised questions as to how committed the leadership of each organization was to plans developed by their predecessors. In addition, some of those interviewed for this report criticized the UNESCO roadmap for being outdated and failing to account for the rapid expansion of mobile devices and digital platforms in the country. Others questioned whether the roadmap was realistic in its scope and timeline, with one INGO representative calling the reform of state media alone “a monumental task.”5

In the absence of movement by Sudan’s government to address the priorities outlined in the roadmap, a group of international media assistance agencies released a separate “consortium plan” outlining a way forward for media reform in Sudan. This competing plan, submitted to international donors and the Sudanese information ministry, addressed content creation, state media reform, and support for grassroots media outlets. The October 2021 coup removed any suspense as to which plan would gain favor, as the resurgence of the military effectively suspended all reforms.

Lacking direction from the Sudanese government, media assistance efforts during the reform period were short term in focus and sometimes uncoordinated. Some projects did not have significant involvement by any Sudanese entities. Despite forecasts by some interviewed for this report that donors would spend $5–10 million on the Sudanese media sector in 2021, donors appeared to be mostly in a holding pattern due to instability in the government—a position that looks prudent in light of the October 2021 coup.

Internationally funded media projects during the reform period focused on journalist skills trainings, COVID-19 awareness, averting violent extremism, media management, and preventing gender-based violence. The Dutch government, via Free Press Unlimited, also funded Radio Dabanga, one of the most significant independent news outlets in the country. Once a shortwave station covering Darfur, it has grown its online presence and coverage area to include much of the nation.

A final note on media assistance in Sudan: In any discussion of aid to Khartoum, it’s important to consider that while Western nations had influence with the civilian arm of the Sudanese transitional government, they were not the only significant donors. Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates provided substantial aid to the Sudanese military in recent years and retain much influence. Given their own governance systems, these allies likely have not, and will not, advocate for democratization or media reforms in their discussions with Sudan’s generals.

Conclusions and Recommendations

From 2019 to 2021, Sudan experienced a brief window to enact media reforms. The civilian government, international community, independent journalists, and the country’s small group of civil society organizations all demonstrated will to advance a vision for a plural and independent media system. However, during the same period, the military part of the transitional government showed that it preferred to control the media and actively undermined its civilian counterparts. The public, which could have helped advance the issue in the face of military opposition, did not demonstrate significant interest in the issue. Since the October 2021 coup, it appears the military’s chosen course will win the day—at least in the short to medium term.

Given Sudan’s weak civil society and media institutions, and many governance challenges, it’s reasonable to conclude that the window for a transition to democracy was simply too narrow for meaningful media reforms to succeed. Changing media laws is near-impossible when there is no legislative assembly in place, and enforcing them is challenging in the absence of an independent court system. In Sudan’s case, a baseline of governance, security, judicial competence, and economic opportunity appear to be key precursors to addressing media reforms.

Despite this, there is energy, expertise, and ideas for how to advance democratic media in the country. Sudanese media professionals, international media assistance organizations, donors, and reformers within the Ministry of Culture and Information continue to work together despite the formidable challenges they face. There is activism for media rights and legal reforms, and there are robust anti-disinformation campaigns seeking to reclaim the narrative of Sudan’s revolution on social media.

In the wake of the October coup, much will depend on whether civilians are given a meaningful role in governance and how tightly the military restricts the media space. Even in a more restrictive environment, media donors and assistance actors may be able to chalk up some short-term wins by providing core funding for existing independent media outlets, civil society organizations, and human rights groups—including those based outside Sudan. There may also be virtue in Western donors pushing for the creation of one or more Sudanese institutions to drive short-term media reform—should the political environment allow it.

At the same time, international donors must plan for the long term by helping to develop local civil society groups so they can become agents of reform. Donor nations should utilize their diplomatic services to ensure that media reform is not forgotten in interactions both with the Sudanese military and with other donors who have influence over it, such as Egypt and the Gulf States. To be ready for the next reform window, major donors might also work together to integrate the two media reform roadmaps authored by UNESCO and the consortium of media assistance organizations, retaining the most realistic, locally owned aspects of the two plans. Aid agencies should be required to minimize their expatriate staff and recruit local administrators when possible.

Finally, media donors should consider creating a public interest media fund for Sudan to support small Sudanese-run independent media outlets, production houses, and media-supporting civil society organizations such as editors’ guilds and media trade associations. Gen. al-Burhan, the leader of the October coup, has said the military will step back from politics once a political consensus is achieved through elections, which are currently scheduled for 2023.6 Should that come to pass, investments made now in fostering Sudanese institutions that can advance media reforms may pay dividends under a future civilian regime.

Header Photo Credit: Esam Idris / CC BY-SA 4.0

To read the working paper for this case study, as well as the synthesis report and the other country case studies, please see the project landing page here.

Footnotes

- Sudanese freelance journalist in an interview with the authors, September 13, 2020.

- Senior Sudanese analyst in an interview with the authors, March 30, 2021.

- ORB International, Cabinet Office Sudan, Winter 2020/21 Report (London and Charlottesville, VA: ORB International, 2021), unavailable online.

- UNESCO, Media Reform Roadmap for Sudan (Paris: UNESCO, 2020), https://sudan.un.org/sites/default/files/2020-12/Media%20Reform%20Roadmap%20for%20Sudan.pdf.

- INGO representative in an interview with the authors, 2021.

- “Sudan junta head: ‘Military will quit politics once consensus reached via elections,’” Dabanga, February 13, 2022, https://www.dabangasudan.org/en/all-news/article/sudan-junta-head-military-will-quit-politics-once-consensus-reached-via-elections.