Key Findings

Funding to support independent media remains a small, but vital part of international assistance. But while the share of aid directed at this issue remains steady, there are signs that priorities within this field of international support may be shifting. This report looks at the trends identified by CIMA in its efforts to profile the major donors in the field of media development assistance, situating the emerging priorities within a brief history of the field. Assistance to media development, the report suggests, is beginning to acknowledge the importance of supporting media ecosystems more broadly, though perhaps not as quickly as some observers would like. The report also highlights several other important findings.

• Media development is emerging as a distinct funding area, but the lack of common budget codes still makes it difficult to trace spending on this topic.

• Though North-South funding continues to predominate, funds from new private donors and new governmental donors are beginning to reshape the sector.

• Research on media and media development, while not entirely neglected, remains a low priority in spite of being a recognized need.

Introduction

In the current era of resurgent authoritarianism, independent media has become ever more important. As research by CIMA and others has shown, the health of independent media is linked to the health of democracy, with each powering the other. 1 Conversely, a lack of credible, reliable information may exacerbate humanitarian crises, state fragility, and violent extremism. 2 Furthermore, the link—between media and the function of democratic politics—is only likely to be strengthened by the growing pervasiveness of digital communication in people’s lives. 3

In the current era of resurgent authoritarianism, independent media has become ever more important. As research by CIMA and others has shown, the health of independent media is linked to the health of democracy, with each powering the other. 1 Conversely, a lack of credible, reliable information may exacerbate humanitarian crises, state fragility, and violent extremism. 2 Furthermore, the link—between media and the function of democratic politics—is only likely to be strengthened by the growing pervasiveness of digital communication in people’s lives. 3

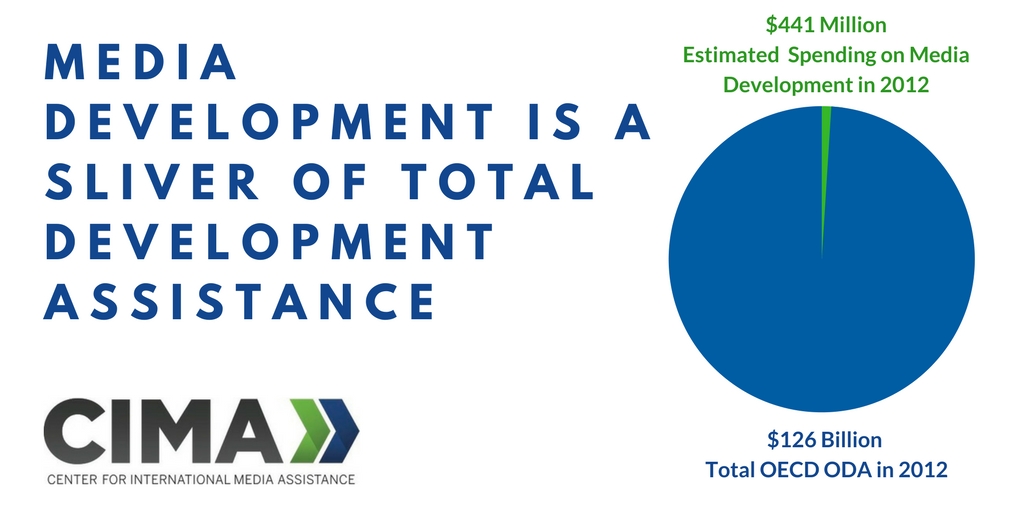

And yet support for independent media around the world makes up only a sliver of foreign assistance. While numbers fluctuate over time, independent media funding has recently constituted approximately 2 percent of total support for good governance by OECD member countries—or less than half a percent of official development assistance overall. 4 However small a proportion of donor portfolios it represents, this funding is crucial for sustaining independent media around the world: it shapes the policies and regulations that protect freedom of expression, it enables local radio stations to keep communities informed, and guarantees that young journalists are well trained and equipped to fulfill their vital public service functions, amidst the rapid spread of digital communication. Indeed, this funding is deployed for a variety of objectives, some new and some old, which alludes to the purpose of this report.

To better understand how this small but vital segment of development assistance is being directed, CIMA commissioned a series of donor profiles, based on a standardized survey, to better explicate how public and private donors are supporting freedom of expression and independent media. Located on the CIMA website, each donor profile contains details about the organization’s background, its current thematic priorities, details about funding, and examples illustrating the types of media development projects funded. 5

This report provides a summary of the information gleaned from the donor profiles, situating it against a brief background of media development assistance. What emerges from this exercise is that media assistance is a shifting field, and that it is beginning to reconcile itself with the need to support media ecosystems more broadly, though perhaps not as quickly as some observers would like. It concludes with a few considerations for how the financiers, practitioners, and beneficiaries of media assistance can continue to keep the field moving in a coherent and strategic direction.

Funding for media development from major donors (annually, when available)

| Media Development Donor | Amount | Fiscal Year(s) |

|---|---|---|

| US Government | $65,401,202.00 | 2015 |

| Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Netherlands | $39,000,000.00 | 2014 |

| Knight Foundation | $35,000,000.00 | 2014 |

| Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency | $25,000,000.00 | 2013 |

| Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation | $23,000,000.00 | 2016 |

| German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Develpment | $21,000,000.00 | 2015 |

| Government of Norway | $20,000,000.00 | 2015 |

| National Endowment for Democracy | $18,700,000.00 | 2015 |

| Open Society Foundations | $12,800,000.00 | 2014 |

| French Ministry of Foreign Affairs | $11,200,000.00 | 2015 |

| DANIDA | $6,000,000.00 | 2015 |

| Media Development Investment Fund | $4,160,000.00 | 2015 |

| Japan International Cooperation Agency | $4,020,000.00 | 2015 |

| European Endowment for Democracy | $2,800,000.00 | 2015 |

| UNESCO | $1,000,000.00 | 2015 |

| Skoll Foundation | $850,000.00 | 2014 |

| Donors that have not reported annual figures. | ||

| Ford Foundation | $103,000,000.00 | 2008-2015 |

| Global Affairs Canada | $55,900,000.00 | 2014-2019 |

| Omidyar Network | $22,500,000.00 | Since 2004 |

| Jigsaw (Formerly Google Ideas) | $560,000.00 | Since 2010 |

A Brief History of International Media Assistance

Although media development as a part of democracy promotion began around the mid-1980s in Latin America, the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s provided an opportunity to launch large, ambitious, and multi-year programs designed to seed and support independent media in Eastern Europe and Eurasia. Beginning with basic journalism training, programs also moved to address multiple aspects of the basic ecosystem supporting independent media, including legal reforms, business development, advocacy institutions, ombudsmen, and development of legislative and regulatory models. Many initiatives also supported the transition of state broadcasters into public service broadcasters, based on the model of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) and a host of others.6

Awareness of media’s role in potentially promulgating violence—including the genocide in Rwanda—led to more initiatives in conflict-affected and fragile states, with an explicit focus on peace-building. Media assistance began to move farther afield to countries like Bosnia and Croatia; to African countries such as Burundi, Congo, and Liberia; and newly independent countries like East Timor and Kosovo7. More recently, some donors have embraced support for independent media as part of the broader good governance, transparency, and accountability agenda.

But understanding how donors conceptualize and support media development has not always been easy. A 2009 effort to survey mainstream development donors about their knowledge of media development revealed that many donor organizations used the media in partner countries to communicate about development goals, but few engaged in programs intended to strengthen the media sector itself.8 Moreover, while governance advisors were interested in working with the media in their respective countries, very few understood media development and its role in good governance.9

Other, more recent survey efforts have revealed a slightly deeper understanding of media development, as well as the entrance of new funders. Philanthropists who come from the world of digital technology have sought to create new models of philanthropy that emphasize the roles and principles of digital media.10 Major OECD donors now fund media development at various levels as part of their overall work on governance. Over the past several years, a variety of donors have also prioritized related endeavors that can overlap with media development, such as information and communication technology for development (ICT4D), technology for transparency and accountability, and open government data. The landscape has shifted significantly since the field’s inception, and as the profiles show, it continues to shift still.

Donor Profiles: What They Reveal

Before discussing the donor profiles, a few caveats are in order. First, the donor profile project is ongoing, and this report was based on the eighteen responses received at the time of writing.11 While this sample includes many major donors, it is not perfectly representative of the universe of media development donors, or of their priorities. Moreover, while the survey contained standardized questions regarding funding levels, priorities, and rationales for media assistance, many donors did not answer all the questions, which reduced the ability to compare systematically across donors. The survey methodology will continue to be refined in coming years, while the CIMA donor profile website will be updated on a rolling basis.

Before discussing the donor profiles, a few caveats are in order. First, the donor profile project is ongoing, and this report was based on the eighteen responses received at the time of writing.11 While this sample includes many major donors, it is not perfectly representative of the universe of media development donors, or of their priorities. Moreover, while the survey contained standardized questions regarding funding levels, priorities, and rationales for media assistance, many donors did not answer all the questions, which reduced the ability to compare systematically across donors. The survey methodology will continue to be refined in coming years, while the CIMA donor profile website will be updated on a rolling basis.

Second, donors categorize their media assistance in different ways, and while the survey attempted to capture the type of programs that typically fall under the rubric of “independent media development,” it remains difficult to compare priorities and particularly funding levels across donor types or over time. While previous studies by CIMA and others have sought to explicitly break down funding by, for instance, OECD-DAC budget codes, donors’ self-reported numbers may not necessarily match up. Public donors, in particular, must try to collect and standardize information that may be spread across several government agencies or bureaucracies, such as the foreign ministry, aid/assistance ministry, defense ministry, and so on. Frequently, the information captured in Official Development Assistance may leave out significant sources of media development-related funding, including defense-related funding. This problem is widespread, and has contributed to a fundamental lack of understanding of the trajectory of media assistance funding since the field’s inception. For the purpose of the survey, donors were asked to rank priorities from a given list, but were given the option of adding a priority if it was not already listed.

Also, not all donors have a common understanding of media development (or “media assistance”). Some donors may include development communication (using media primarily to accomplish development aims rather than seeking to strengthen the media sector itself) and content production in their media assistance figures, while others may not. In a previous OECD/CIMA study, donors also included goals such as public diplomacy in their media assistance figures. The problems of categorization have been exacerbated with the rise of ICT4D, technology for transparency, and open government data as distinct fields of practice. Information about where media assistance is housed programmatically within donor organizations (see accompanying chart) may provide a clue as to the chief rationale for media assistance.

Finally, the donor profiles are exactly that: information provided by donors themselves about their priorities. They do not take into account the perspectives of the recipients of donor funding, nor are they a substitute for objective research about the effectiveness of each donor or media development funding in general. Further research efforts on whether and how effectively donor funding matches recipient needs would help to provide a more complete picture.

High Priorities

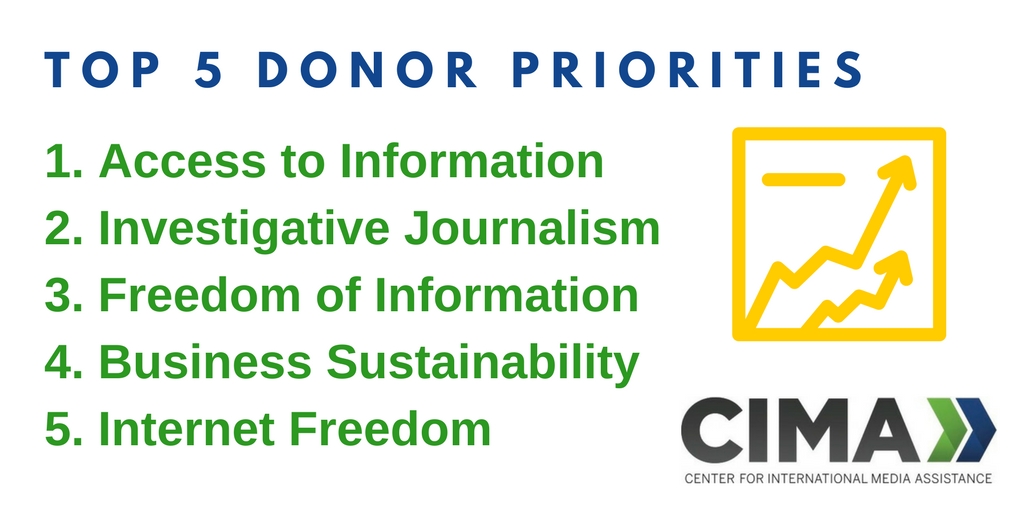

Out of a total of 22 categories, these were the five categories that donors self-identified most often as “high” priorities (in descending rank): access to information, investigative journalism, freedom of information, business sustainability, and Internet freedom.

| Area of support | Number of donors that view this area as "high" priority |

|---|---|

| Access to information | 11 |

| Investigative journalism | 10 |

| Freedom of information | 8 |

| Business sustainability | 7 |

| Internet freedom | 6 |

At a glance, the categories most often listed as high priorities are not necessarily the most traditional, but at the same time feel unsurprising: access to information is the most highly prioritized of all categories, and perhaps perceived as the most fundamental issue. Freedom of information is also seen as fundamental, but can be interpreted somewhat broadly. Internet freedom as a top category of media assistance is a relatively recent development, while business sustainability has long been a top priority of particular donors. Overall, despite the advent of digital media and the multitude of changes wrought within the global media landscape, the priorities of broad media development assistance seem to have shifted only marginally.

That said, early media assistance focused heavily on basic journalism training, which sits just outside the top five most highly prioritized categories. As media development has evolved as a field, critics have questioned the heavy focus on basic journalism training, arguing that a truly independent media sector needs an entire ecosystem to function effectively, one that requires support for business development training, a legal enabling environment, basic access to information, and so on. To the extent that this current mix of high priorities reflects overall current donor priorities, it appears that those critiques have been heard.

Waning donor enthusiasm for basic journalism training has also been substituted, in part, with a growing emphasis on investment in investigative journalism. This trend, however, raises some concerns. Investigative journalism is skill-intensive—drawing on the very best journalists—and resource-intensive, as reporters’ time is taken up with long projects that don’t immediately bear fruit. In many areas where media assistance is required, are such skills and resources adequate to support the push for investigative journalism without compromising the needs for everyday news coverage? It is just not clear whether donors have shifted their focus based on a well-founded assessment of the situation, or whether investigative journalism has simply come into fashion along with the current interest in anti-corruption and good governance. It seems likely that donors have elevated investigative journalism as a kind of shorthand for tackling corruption, but perhaps without much consideration of what media partners actually need.

Internet freedom is another new priority within the media assistance field. Because of this, and because the phrase itself is somewhat vague, it is difficult to know exactly what donors mean by citing this as a priority. In the past, activities under “Internet freedom” typically encompassed support for anti-censorship technologies primarily within authoritarian regimes, as well as the training of civil society activists in the safe use of such technology. Donors generally did not focus as strongly on the enabling environment for Internet freedom, specifically the laws and regulations enabling the free flow of information (including but not limited to such issues as intermediary liability, privacy, and surveillance legislation).12 These are politically complicated topics for public donors, and even private donors, to address. That said, if donors now perceive Internet freedom as a part of their total media development assistance, it suggests that they are moving from viewing Internet freedom as a more narrow, technologically focused area of activity to a broader view that encompasses the importance of the entire information ecosystem.

Low Priorities

Out of 22 priorities, these were the eight categories that were least identified by donors as priorities: independent journalism; research on media and freedom of expression; credibility through quality of information; sustainable business model for online media outlets; media innovation within the journalism field; media literacy; accountability/good governance; and support for transforming state broadcasters into public service broadcasters. It is easy to see why some of these categories might not have been listed often as high priorities, or listed at all. Some are overarching priorities, applicable not just to media development but a whole host of activities: accountability/good governance, for instance. Other categories may conceivably be wrapped up in other priorities; for instance, “sustainable business model for online media outlets” could be construed as a sub-category of “business sustainability.” Similarly, “credibility through quality of information” and “independent journalism” may be considered part of “journalism training.”

Interestingly, media literacy was identified by only one donor, Global Affairs Canada, as a priority (although a high priority). Again, that might be because aspects of media literacy are incorporated into other elements of media support or perhaps into broader democracy and governance programming—part of “media skills for civil society organizations,” for example—and thus not explicitly identified as media literacy. Yet media literacy has been highlighted in practitioner discourse over the past few years as an under-funded, ill-understood, yet desperately needed area of programming. Indeed, CIMA published three reports in 2009 on media literacy,13 and a follow-up report in 2013.14 That latest report noted that media literacy was rarely a stand-alone objective in programming, that few practitioners had evaluated programs to determine overall impact, and that media literacy was often viewed as a component within a broader program.15 Three years later, it seems that media literacy remains under-emphasized as a component of media development.

Only one donor (Japanese International Cooperation Agency, or JICA) mentioned transforming state broadcasters into public service broadcasters (PSBs). Following a spate of early donor interest in transforming state broadcasters (primarily in the wake of transitions from authoritarianism), disappointing experiences scared many funders away from this particular activity. Indeed, some media analysts have predicted the death of public service broadcasting in general, due to market pressures, digitalization, and the rise of Internet-accessible news and entertainment.16 Moreover, support for PSBs requires higher funding amounts and a particularly long-term program cycle. In spite of these challenges, media development advocates point to a continued need to support public service broadcasting, especially in the face of worrisome global trends of private media capture: when private media owners collude with government to promote an agenda that serves their interests at the expense of public interest.17

Accounting for the US government's media support

US agencies declined to rank their priorities in the field of media development for this report, but given that the United States is the second largest country contributor to global media development efforts (behind Germany), it is important to acknowledge that contribution in some form. Total support for media development from US agencies has averaged about $70 million in the three most recent fiscal years for which data was available. The following table summarizes State Department and USAID funding to media development FY2013 – FY2015. As CIMA receives more information on the priorities and objectives of this funding, it will publish those separately, or update this report.

US agencies declined to rank their priorities in the field of media development for this report, but given that the United States is the second largest country contributor to global media development efforts (behind Germany), it is important to acknowledge that contribution in some form. Total support for media development from US agencies has averaged about $70 million in the three most recent fiscal years for which data was available. The following table summarizes State Department and USAID funding to media development FY2013 – FY2015. As CIMA receives more information on the priorities and objectives of this funding, it will publish those separately, or update this report.

| FY2013 | FY2014 | FY2015 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TOTAL | $68,738,070 | $74,774,249 | $65,401,202 |

| Africa | $16,223,706 | $12,755,950 | $7,219,335 |

| East Asia and Pacific | $3,751,834 | $2,711,776 | $6,003,843 |

| Europe and Eurasia | $14,789,410 | $14,588,445 | $12,765,203 |

| Near East | $10,000,000 | $14,999,229 | $9,000,000 |

| South and Central Asia | $1,649,700 | $2,030,849 | $2,597,321 |

| Western Hemisphere | $9,967,104 | $6,243,000 | $3,495,500 |

| Democracy, Conflict and Humanitarian (DCHA) | $3,489,816 | $3,995,000 | $3,520,000 |

| Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (DRL) | $8,866,500 | $17,450,000 | $20,800,000 |

Differences Between Private and Public Donors

One might anticipate that private donors would be more willing to engage in so-called “risky” or entrepreneurial areas of media development (i.e., exploring media innovation, models for online media outlets, etc.). It has traditionally been the case that public donors are more constrained in the type of funding they can provide, particularly when it comes to experimentation, tolerance for failure, and the challenges of sustaining processes of long-term change. But those assumptions were not necessarily borne out in riskier areas of media development, or areas where it was difficult to show progress or results. Innovation was prioritized only by the Knight Foundation, while Internet freedom—which arguably might involve risky and difficult-to-measure trials of anti-censorship technologies and platforms—was actually a higher priority for public donors. In fact, it was prioritized by eight out of the ten public donors; whereas just two of the seven private donors listed Internet freedom as a priority.

While “access to information” was the most prioritized issue overall, and nearly unanimously among public donors, only three of the seven private funders who responded to the survey classified it as a high priority. Four of the seven did not even list it as a priority. This might be attributable to the fact that “access to information” may include some form of infrastructure investment, which is more likely to be tackled by public donors, and then as part of their overall development assistance.

Support for content production is universal (at some level of priority) among the private donors, but only prioritized by a few of the public donors. This marks an interesting departure from expected norms, as nearly all donors fund some kind of media content production. It is likely that much content production may be categorized under the specific sectors that the programming is addressing, such as health, sanitation, or gender. This points yet again to the difficulties inherent in categorizing funding.

True Funding Information is Lacking

While funding levels for those years that were available (i.e. provided by donors in the survey) are listed in the accompanying chart, the numbers do not speak for themselves. Without accurate, reliable and consistently measured data from other years, it is difficult to tell whether support for independent media is growing, declining, or holding steady. Moreover, categorizing funding levels and obtaining the right type of data from funders can be difficult, as noted earlier. For the donor profiles, some donors provided funding totals over a range of years, while others provided funding levels for individual years, making it impossible to determine which donors were the top funders of media development in any given year.

For those donors that provided media funding amounts in a given year or period, and for whom total funding levels during the same period were available, it is possible to make some observations about media development funding as a proportion of total budget. As one can see in the chart, even for those donors who know about and commit funds to independent media development, media assistance typically makes up less than 1 percent of overall funding. Exceptions include organizations specifically dedicated to media assistance or to democracy, such as the Knight Foundation, the National Endowment for Democracy (CIMA’s home organization), or the European Endowment for Democracy. While media development advocates have long made the case that an independent media is crucial not just to democracy but to development overall, this level of resource allocation suggests that donors have not been persuaded, or harbor reservations about the field. Indeed, political sensitivities surrounding the media in any given country may continue to make donors particularly wary of engaging in this area of assistance.

Considerations for the Future

Although still in progress, the donor profile process has generated enough data to make possible some general observations.

- Common budget codes are needed. To draw informed conclusions about the amount and nature of total media development funding, a common standard of measurement is necessary. As the donor profiles make clear, information on total donor funding continues to be spotty. Over and over again, analysts must ask whether apples are being compared to apples, and sometimes whether oranges should be included as well. It may be that some form of coordinating body, such as the Global Fund for Media Development, OECD/DAC or UNESCO, needs to actively promulgate a common “code” for understanding budget allocations across private and public funders. Although such an effort would likely be cumbersome and bureaucratically problematic, other endeavors—defining and promoting the use of some common indicators, for instance—have met with a small measure of success. Moreover, the very process of collaborating on uniform budgeting codes might spark a useful discussion within the media development world about priorities, funding levels, and the nature of the field itself.

- Media development continues to emerge as a distinct funding area. There is some indication that within development organizations, media development as a field has emerged as distinct from a one-size-fits-all “any funding that involves media” approach. For instance, the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development, or BMZ, established in 2014 a budget specifically dedicated to freedom of expression, access to information, and media development. Prior to that, media development was funded through other budgets such as education and governance.18 JICA, which has tended to concentrate on pure infrastructure funding in the past, listed journalism training, investigative journalism, and freedom of information as among its current priorities. JICA noted that it has increased its media development support over the past five years, with new (albeit small) projects in South Sudan, Kosovo and Myanmar, and says this “reflects the positive stance of the [Japanese] government in its use of official development assistance to emphasize support for democratization.”19 If more donors can converge on a common understanding of the field, it might make the process of collaborating on budget categorization easier.

- At the same time, the field may also be shifting/expanding. While the term media development is probably not vanishing soon, the extremely high priority assigned to generalized “access to information,” “freedom of information,” and “Internet freedom,” may reflect the fact that the field may be slowly morphing into what some call support for healthy information ecosystems. At its edges, this type of support may also bleed into ICT4D, technology for transparency, and open government data, among other newly emerging areas. As integration of digital technologies becomes even more seamless, and activists, practitioners and donors increasingly emphasize a broader understanding of the enabling environment, the information ecosystem rubric may emerge as a more common and perhaps more holistic way to conceptualize and fund this field.

- Research continues to be needed yet underfunded. Research on media and media development, while not neglected, is not currently highly prioritized by donors. Previous studies have noted that there remain unanswered fundamental questions concerning the linkages between media, development, and democracy, with plenty of opportunities for application in the real world. In particular, practitioners have called for further exploration into, inter alia: the impact of media assistance on media as well as other development sectors; the development and use of alternate indices to describe and measure media freedom; better understanding of media audiences and media users, particularly from a development point of view; and the effectiveness (or lack thereof) of existing media development funding in achieving its aims.20 Amid the current pressure to show results for international assistance, such research is especially vital to the effort to formulate better systems of monitoring and evaluation in the field.

- North-South funding still predominates, but this is changing. While the entrance of relatively new private donors such as the Omidyar Network and Jigsaw (formerly Google Ideas) has changed the funding landscape, one element seems to remain constant: with the exception of JICA, all the other donors who responded to the survey are located in North America and Europe. While the survey is not necessarily representative of the entire universe of donors, it does represent the major funders of media development. While practitioners and donors alike have sought to facilitate the development of more South-South funding and exchanges in the media development field, to date this has yet to fully materialize. That said, there are certainly new donors in the world of media assistance whose activities are not captured here; China, for instance, has been active in funding media outlets and training journalists in Africa. Including China as a “media development donor” is somewhat problematic, however, as the media development field traditionally emphasizes core concepts that are anathema within the Chinese system: freedom of the press, journalist and media outlet independence, and the importance of the media in holding governments to account. How the field may change as new donors make their presence felt is an open question.

In collecting these donor profiles, CIMA has provided a snapshot of the current state of media assistance. Although imperfect, it is perhaps the only endeavor that seeks to collect up-to-date data about the current landscape of both private and public funding of media assistance. The insights gleaned here, as well as the gaps revealed, should serve to spark further conversations on the future of this field.

Footnotes

- Karin Deutsch Karlekar and Lee B. Becker, By the Numbers: Tracing the Statistical Correlation Between Press Freedom and Democracy (Center for International Media Assistance, April 22, 2014).

http://www.cima.ned.org/publication/by_the_numbers___tracing_the_statistical_correlation_between_press_freedom_and_democracy/ - Shanthi Kalathil, Adam Kaplan and Langlois, John, Towards A New Model: Media and Communication in Post-Conflict and Fragile States (The World Bank, 2008)

http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTGOVACC/Resources/CommGAPNewModelWeb.pdf”. See also When Information Saves Lives: 2011 Humanitarian Annual Report. Internews, 2011. - Frank Esser and Jesper Strömbäck, eds., Mediatization of Politics: Understanding the Transformation of Western Democracies (Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014).

- Eduardo González Cauhapé-Cazaux and Shanthi Kalathil, Official Development Assistance for Media: Figures and Findings (Center for International Media Assistance and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2015). https://www.oecd.org/dac/governance-peace/docs/CIMA.pdf

- See http://www.cima.ned.org/donor-profiles/

- Krishna Kumar, Promoting Independent Media: Strategies for Democracy Assistance (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 2006), 5.

- Ibid., 6.

- Shanthi Kalathil, Developing Independent Media as an Institution of Accountable Governance (The World Bank, 2011), 1. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTGOVACC/Resources/Mediatoolkit.pdf

- Ibid.

- Anne Nelson, Continental Shift: New Trends in Private U.S. Funding for Media Development (Center for International Media Assistance, 2011), 4. http://www.cima.ned.org/publication/continental_shift__new_trends_in_private_u_s__funding_for_media_development/

- Responses to the survey were received from: Danish International Development Agency (DANIDA), European Endowment for Democracy, French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development,

Global Affairs Canada, Government of Norway, Japan International Cooperation Agency, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands, Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Jigsaw (formerly Google Ideas), Knight Foundation, Media Development Investment Fund, Omidyar Network, Open Society Foundations, Skoll Foundation, and Ford Foundation. - Shanthi Kalathil. “Interred with Its Bones: The Death of Internet Freedom,” I/S: A Journal of Law and Policy for the Information Age 12, no. 1 (2016). http://moritzlaw.osu.edu/students/groups/is/files/2016/09/6-Kalathil.pdf

- See Susan D. Moeller, Media Literacy: Citizen Journalists (Center for International Media Assistance, 2009). http://www.cima.ned.org/resource/media-literacy-citizen-journalists/ and

Susan D. Moeller, Media Literacy: Understanding the News (Center for International Media Assistance, 2009). http://www.cima.ned.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CIMA-Media_Literacy_Understanding_The_News-Report.pdf and

Paul Mihailidis, Media Literacy: Empowering Youth Worldwide (Center for International Media Assistance, 2009).

http://www.cima.ned.org/resource/media-literacy-empowering-youth-worldwide/. - John Burgess, Media Literacy 2.0: A Sampling of Programs Around the World.

An Update for the Center for International Media Assistance (Center for International Media Assistance, 2013). - Ibid., 2.

- Susan Abbot, Rethinking Public Service Broadcasting’s Place in

International Media Development (Center for International Media Assistance, 2016), 5. http://www.cima.ned.org/publication/psb/ - Ibid, 1.

- “CIMA Donor Profile: German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development,” Center for International Media Assistance, accessed September 23, 2016, http://www.cima.ned.org/donor-profiles/german-federal-ministry-economic-cooperation-development-bmz/.

- “CIMA Donor Profile: Japan International Cooperation Agency,” Center for International Media Assistance, accessed September 23, 2016, http://www.cima.ned.org/donor-profiles/japanese-international-cooperation-agency-jica/.

- Amelia Arsenault and Shawn Powers, Media Map: Review of Literature (Internews, Media Map and The World Bank Institute, 2010). http://www.mediamapresource.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Media-Map-Literature-Review-Final.pdf).

See also Mark Nelson and Tara Susman-Pena, Rethinking Media Development (Internews, Media Map and The World Bank Institute, 2012). http://www.mediamapresource.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Rethinking-Media-Dev.web_1.pdf.