Key Findings

The so-called Right to be Forgotten (RTBF) refers to the removal of content from either search engine indexes or even the entire internet so that it is not readily accessible to end users. While the concept emerged out of a European legal tradition that favors the privacy of non-public individuals, in practice it has led to the censorship of information relevant to the public interest. It has endangered press freedom by leading to the removal of news articles, and it has hindered media development by erasing content from the digital public record.

• The implementation of the Right to be Forgotten within Europe has led to cases where news content has been censored.

• The legal concept is already being invoked in many contexts outside of Europe in ways that enable press censorship.

• Negotiating individual privacy with the public’s right to know is a balancing act for which there are no easy solutions, but it is one that has substantial implications for media development.

Introduction

As people connect to the internet worldwide, they are doing so in a time when the details of their lives are increasingly digitized and stored in massive data centers. Everything from their list of friends and biometric data to personal financial transactions and work history are being uploaded to servers in the cloud. This data often cross international borders when they are retrieved in different locations and from different digital pathways of the internet. Much of these data are, in fact, publicly accessible. In many respects, the internet now serves as a sort of public archive. This has been a boon to journalists in particular since it enables them to access more information and facilitates reporting that previously would have been virtually impossible.

As expansive as the amount of information available via the internet is, however, sometimes the most valuable information is what cannot be found. This is increasingly the case as some governments and private citizens are trying to limit what can easily be discovered online, which is also reflected by a growing body of so-called Right to Be Forgotten (RTBF) legislation. The Right to Be Forgotten generally refers to the de-indexing, or even total removal, of information on the internet, especially from search engines, so that it is not readily accessible to end users.1 Having first emerged within European jurisprudence, it is now being applied in other contexts with different legal frameworks. Yet, how can democracies function properly if citizens are ultimately denied the right to access information about, for example, public officials, government ledgers, or corporate filings?

An example Google search where some results have been removed due to Right to be Forgotten requests in Europe.

The right to information, as codified in Article 19 of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights2 is a cornerstone of press freedom. Information, however, is increasingly controlled by powerful gatekeepers and subject to the interpretations of judges, government officials, and autocratic leaders—many of whom have a particular disdain for press freedom, transparency, and democratic values. While societies must engage in legitimate debates about what information should be public and who should have control over that wealth of data, they must find policy solutions that do not chip away at fundamental democratic values, such as the right to information.

RTBF legislation is rapidly developing at a time when freedom of expression online is increasingly circumscribed, and governments are finding new ways to stifle dissent and press freedom.3 Accusations of “fake news” are rampant to the point that such discourse is emboldening governments to use it to justify censorship,4 and internet shutdowns are now commonplace around the world.5 New rationales for censorship are being developed in the digital age, and the RTBF is one of the principal legal tools being adopted by those who seek to control information, which is why it poses a significant challenge to press freedom.6

This report will focus on how RTBF laws and jurisprudence are already impacting content accessibility and what effects they will likely produce in the near future. It also provides an in-depth look at the ways the constellation of policies surrounding RTBF implementation threaten media development—specifically the circulation of objective, high-quality information—by highlighting how it has the power to

- Mandate newspapers and other media outlets to hide search results to relevant journalistic content, making such content less accessible and amplifying chilling effects on the type of content produced;

- Challenge the circulation of relevant, high-quality news and information, such as by retroactively censoring content produced by news and media outlets;

- Disrupt the archival history of information, one of the cornerstones of digital society, and impede the collection of data for news stories and research by making archived information inaccessible; and

- Empower governments with another tool to curb journalism and free expression.

Ultimately, in order for media ecosystems to thrive, citizens must have access to high-quality information, yet the media sector has been largely absent from the debate on the RTBF.7 This lack of engagement has meant that the fundamentals of media freedom are being undermined as new legal frameworks that govern content online are being implemented.

The Right To Be Forgotten Endangers Public Information

At first glance, RTBF legislation may seem rather harmless, or even beneficial, especially since it addresses a growing problem in the digital age. If someone uses the internet, it is almost impossible to escape the record of their past since a significant amount of content, such as photos, status updates, and videos can be stored on cloud data servers almost indefinitely. Even individuals who do not use the internet, or intentionally avoid using specific platforms, will often find their information online.8 As George Brock, a professor of journalism at City University London, wrote, “People who have had long-ago brushes with the law or bankruptcy would prefer such information not to be at the top of search results on their name. Foolish pranks immortalized on Facebook may be harming someone’s chances of getting a job.”9 Moreover, just like the right to information is paramount for press freedom, the right to privacy is as well—lest a reporter’s sources be uncovered, a tip-off quashed, or even their very lives be endangered. According to Brock, however, the RTBF “puts privacy and free speech on a collision course.”

The collision course Brock refers to stems from the tension that exists between the right to information (“the right to know”) on the one hand, and personal privacy and what should be considered public record on the other (“the right to inform”).10 After all, there are many things people do not necessarily want the world to know or have access to—for example, passwords, bank account numbers, intimate and private conversations, addresses of loved ones, children’s photos, private identification information such as Social Security numbers, and medical histories. Yet, considering that perception is largely shaped by the information people have access to, the public realm is one that demands transparency, accountability, and the ability to reevaluate information as its relevance potentially changes due to evolving circumstances or new ways to interpret data11—for example, if an investigation about misuse of taxpayer funds by an elected official is reopened due to the revelation of new evidence.

Indeed, determining what information is relevant and who has the power to determine its relevance over time is central to press freedom and democracy itself.

This is also where the RTBF has major implications for journalists in particular. Journalism is built on a network of links, references, and sources, and the RTBF is eroding segments of this information, or in some cases, altering or removing it altogether. While it is easy to assume digital formats are permanent, a form of digital decay called “link rot”—a phenomenon that refers to data becoming corrupted over time so that they are no longer accessible—is already undermining that assumption.12 Link rot occurs when websites are restructured, entities go out of business, or content hosted on websites is otherwise inaccessible due to problems redirecting to the site, rendering information unreachable. Since “journalism has traditionally acted as a public record, [link] decay has serious implications on the credibility of media brands.”13

In sum, not only are archives—the foundation of information management and knowledge—under threat, but the RTBF also has the insidious effect of empowering governments with the ability to de-index information from public scrutiny and censor content.

The Emergence Of The So-Called Right To Be Forgotten In The Digital Context

The RTBF emerged out of various privacy and data protection debates in certain European countries.14 The principles underlying the concept have existed for decades, however. As Jeffrey Rosen stressed in the Stanford Law Review: “In Europe, the intellectual roots of the right to be forgotten can be found in French [and Italian15] law, which recognizes ‘le droit à l’oubli’—or the ‘right of oblivion’—a right that allows a convicted criminal who has served his time and been rehabilitated to object to the publication of the facts of his conviction and incarceration.”16 The RTBF in its contemporary, digital form first took shape in 2014 thanks to a Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU)17 case that pitted Google against Mario Costeja González, a Spanish citizen.18

The RTBF emerged out of various privacy and data protection debates in certain European countries.14 The principles underlying the concept have existed for decades, however. As Jeffrey Rosen stressed in the Stanford Law Review: “In Europe, the intellectual roots of the right to be forgotten can be found in French [and Italian15] law, which recognizes ‘le droit à l’oubli’—or the ‘right of oblivion’—a right that allows a convicted criminal who has served his time and been rehabilitated to object to the publication of the facts of his conviction and incarceration.”16 The RTBF in its contemporary, digital form first took shape in 2014 thanks to a Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU)17 case that pitted Google against Mario Costeja González, a Spanish citizen.18

González was unhappy that a notice dating from 1998 concerning the auction of his repossessed home on the website of the Catalonian newspaper La Vanguardia appeared in the results of a Google search when people looked up his name. 19 He claimed this infringed on his privacy rights because the proceedings concerning him had been fully resolved for a number of years and he had paid his debts. He argued that references to these proceedings were hurting his public image and potentially even his business by giving potential clients and partners a negative impression of his financial and legal situation— as well as tarnishing his perceived trustworthiness.

González’s lawsuit sought to force La Vanguardia to either remove or alter the pages in question so that the personal data relating to him no longer appeared, and that Google be required to remove the personal data relating to him so that it no longer appeared in the search results.20 The initial Spanish court that heard the case in 2010 decided that La Vanguardia’s archive should not be altered. Subsequently, however, Spain’s data protection authority21 ruled that Google should remove the links to this information from its search engine. Google then challenged the ruling in Spain’s highest national court,22 In May 2014, the CJEU ruled in favor of González on three grounds.

By doing so, the court set the standard for jurisprudence and legal precedent in Europe.

The Implications of the EU's Court of Justice (CJEU) Decision

The CJEU’s actions thrust the RTBF into the spotlight of various debates regarding privacy, transparency, internet regulation, and the role of government in content policing.23 Furthermore, González’s case24 explicitly emphasized three issues, each offering unique implications for media freedom:

1. Data protection laws: Whether the European Union’s (EU’s) 1995 Data Protection Directive (DPD) (95/46)25 applied to search engines26

The court focused on the role of technology companies since “search engines [are] the primary means of accessing information, thus [they have developed] a gatekeeping function.”27 The court affirmed that search engines are controllers of personal data—therefore, they are responsible for complying with EU data protection laws28—and postured the RTBF as a key issue in the EU’s new General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR),29 which includes a provision on the RTBF.30

2. Territoriality: Whether EU law and the DPD applied to Google Spain, given that the company’s data processing server was in the United States at the time

The court ruled that regardless of the location of a physical server (i.e., a search engine or social media platform) operated by a company, when processing data generated within Europe, European law and jurisprudence applies.31 This means that the company must comply with the relevant regulation in order to continue operating within the EU.32 Moreover, as the RTBF continues to evolve in Europe, new judgments are also expanding the reach of the courts vis-à-vis data regulation. For instance, the Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés, the French data protection authority, now mandates that Google de-index sites throughout the entire EU,33 not just the individual countries where the RTBF request originated from34—meaning instead of de-indexing information from just google.uk, google.ro, google.de, or google.fr, it would need to do so for all of Google’s websites operating within EU member states, and could potentially expand to all of Google’s global websites (e.g., google.com), even those outside of the EU so that no one, regardless of their location, would be able to find the information.35

3. Intermediary liability: Whether an individual has the right to request that their personal data be removed from accessibility via a search engine

The court ruled that individuals have the right, under certain conditions,36 to ask intermediaries to remove links with personal information, such as when the information is inaccurate, inadequate, irrelevant, or excessive for the purposes of data processing.37 Additionally, the CJEU explicitly clarified that the Right to Be Forgotten is not absolute but will always need to be balanced against “other fundamental rights,” such as the freedom of expression and of the media.38 The court also mandated that a case-by-case assessment is needed, and must take into consideration the type of information in question, its sensitivity for the individual’s private life, and the interest of the public in having access to that information. Furthermore, the court later underscored that “the role the person requesting the deletion plays in public life might also be relevant.”39

Worrying Implications for Media Freedom

While perhaps well-intentioned, the inherent dangers outlined in the CJEU ruling stem from how the ruling empowers individuals and states to censor content. This has already had an impact in Europe.

Just as link rot is imperiling archival data and the rich, robust network of hyperlinks that both journalists and end users rely on, the RTBF is ultimately encouraging voluntary data decay as well. For example, since the ruling was upheld, courts in Italy and Belgium have ordered news media archives to be altered.40 In Italy, and due to a situation similar to González’s experience, the highest court upheld a ruling in 2016 stipulating that after a period of two years, an article in an online news archive is allowed to expire—the media outlet in question being a small online publisher called Primadanoi. This led to the morphing of RTBF into what Athalie Matthews, writing for The Guardian, called “The right to remove inconvenient journalism from archives after two years.”41 In Belgium, the newspaper Le Soir was ordered to remove information from its archives after a member of the public, who had been involved in a traffic accident, sued them, demanding all reference to the matter be expunged from the paper’s archives.42 Thus, concrete examples of the RTBF impinging on media freedom have already emerged in Europe.

The transparency reports of many internet platforms also reflect the increase in government censorship in general. For instance, Google,43 Apple,44 Facebook,45 and Twitter,46 among others, offer information about the type of content governments ask to be removed or other requests for user information.47 Across the board, such requests have risen significantly since 2014. Many of the requests have specifically cited reasons related to “national security.

Google, for example, received 4,931 requests to remove content from various governments around the world as of December 31, 2014. By December 31, 2016, this number jumped to 15,961—a 223.69 percent increase.48

Moreover, since the RTBF ruling was handed down, Google received more than a million RTBF-related requests from end users within the EU to de-index information between 2014 and 2016, and removed 551,024, or about 43 percent, of the Uniform Resource Locators (URLs)49 requested.50 This illustrates how RTBF legislation and similar policies have potentially amplified efforts by governments and citizens to remove content from search engines and digital archives.

The Right to be Forgotten Beyond Europe

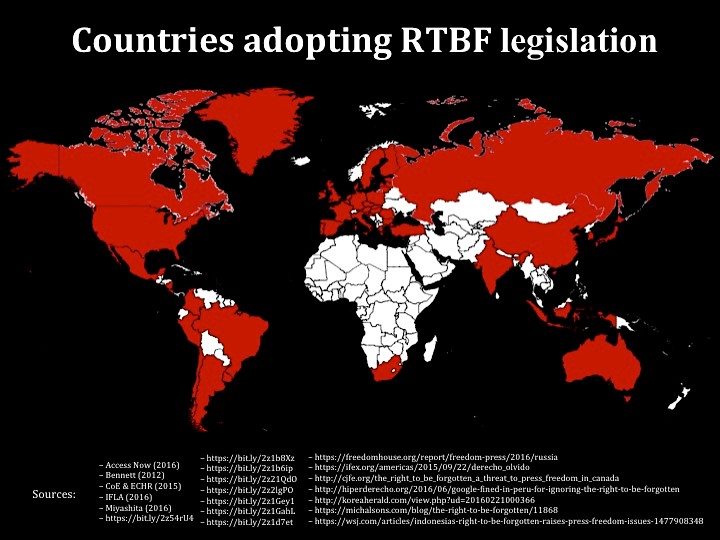

The advent of RTBF jurisprudence in Europe has led other governments around the world to emulate the concept by passing new laws or implementing new data retention policies.

The implementation of RTBF is currently evolving, and has been transformed outside of Europe in ways that make it potentially more pernicious to the media environment, which directly impacts press freedom.

The rise of RTBF legislation is taking place in many countries with varying degrees of democratization. In these contexts, the principles that underpinned the RTBF within the EU—including the respect for freedom of expression and the rule of law—are not necessary valued or upheld. This can quickly lead to scenarios where news outlets and internet platforms are ordered to censor content.51 Such actions can lead to chilling effects and/or self-censorship depending on the kind of content that is consistently requested to be removed because it jeopardizes the “general social standard that published content can be freely discussed.”52 Ultimately these limits to freedom of expression endanger media freedom.

The graphic above illustrates the countries and territories where RTBF legislation is being adopted (those in red), mainly concentrated in the Americas, Europe, and the Global North.

The parallels between government requests to remove content and the fulfillment of legally sanctioned RTBF requests run deep. This is far from merely cynical speculation. ARTICLE 19 warned against the same in a 2016 report.53 They stressed that several governments—many of which have a poor record on freedom of expression or want to undermine the free flow of information, such as Turkey54—have adopted, are in the process of drafting, or are looking to adopt new legislation on the RTBF, but will likely disregard the considerations for free expression that were recognized by the CJEU. Moreover, the RTBF has undoubtedly opened up new social and legal spaces where elites in particular have embraced the RTBF to censor content. 55

Hence, the spread of RTBF to international jurisdictions has led to a reinterpretation of the term guised in language reflecting particular, cultural, legal, and/or political contexts but whose ultimate purpose is censorship—often involving removing content that harms personal honor or damages one’s reputation.

This could not be more apparent than in Russia. Its version of an RTBF law came into force in January 2016. The law gives Russian citizens the right to request search engines to remove links about them that are in violation of Russian law, inaccurate, out of date, or irrelevant because of subsequent events or actions taken by the citizens. Additionally, the law requires the complete removal of content from a search engine index—rather than merely de-indexing—and it does not exclude information related to a public figure or of the public interest.

Although the Russian variation of RTBF legislation is one of the more detrimental incarnations, the reality as reflected globally is far more nuanced. Given that the RTBF is still a relatively new legal concept, relevant legislation and policy around the world tend to reflect three distinct potential outcomes for those defending press freedom. These outcomes are described below as a forecast for how the RTBF may continue to evolve based on three scenarios involving real RTBF cases.

Right to be Forgotten Forecast: Three Scenarios Based on Current Precedent

Scenario I: The RTBF as a tool of government censorship

While the case of Russia is a notable example of the impact RTBF legislation can have on publicly accessible information and content policing, the RTBF in Hong Kong has never been formally established. Yet, a case involving de-listed information has already set a precedent in China. There is legislation in place in Hong Kong meant to protect privacy rights and personal data: the Personal Data (Privacy) Ordinance (PDPO).56 What is problematic about the PDPO, however, is that it empowers a government official, known as the privacy commissioner, with nearly absolute authority to determine what is violating personal data protection in the public domain and what is not.57 This was central to a case that received much attention among privacy and accountability advocates involving the silencing of David Webb, the owner of webb-site.com, which provides information on corporate governance in Hong Kong as well as an archive of publicly available court judgments searchable by name.

The names in a matrimonial case were redacted by a court in 2010 and 2012, and the Hong Kong privacy commissioner ordered that Webb remove the names in the court documents that were archived on the website as per the Hong Kong’s PDPO.58 Webb appealed, arguing that the personal data had been collected and published when they were publicly available. The Hong Kong Administrative Appeals Board concluded in November 2015 that individuals in Hong Kong have the right to have their online personal information deleted, even in a situation where such information is in the public domain, and upheld the privacy commissioner’s orders.59

Not only did the case establish judicial precedent to further implement the RTBF in Hong Kong, but it further empowered the privacy commissioner. And with China’s grip tightening on Hong Kong,60 the implications for journalists and access to information are clear since China has one of the worst landscapes in terms of press freedom and freedom of expression.61

Scenario II: Elite capture of the RTBF

Another scenario where RTBF legislation could harm a media environment involves greater use by elites to present carefully crafted public images, hide information from the public, and/or control information by limiting what is publicly accessible to both citizens and journalists. An ongoing case in Mexico demonstrates this point especially well. The conflict between the RTBF and press freedom in Mexico is similar in nature to the impetus that was behind González’s case in Spain. Mexico’s RTBF is largely dictated by Section IV (the right to cancel and erase the processing of personal data) and Section V (the right to oppose data processing and storage) of the Federal Personal Data Protection Processed by Private Entities Act,62 which came into force in 2011.The rights outlined in this piece of legislation are similar to the right of erasure established in the European Data Protection Directive 95/46/EC, the basis for the CJEU case.63 This act laid the foundation for the RTBF to be invoked during a case that involved a media company and published data. In 2014, a Mexican transportation mogul, Carlos Sánchez de la Peña, wanted links with negative comments about his family’s business dealings removed from Google Mexico, including the government’s bailout of bad loans, specifically from Fortuna magazine that published the story in 2007.

In National Institute for the Access to Information (INAI), Carlos Sánchez de la Peña v. Google México, S. de R.L., PPD.0094/14, the INAI ruled, “The request met the privacy law requirements that allow for the removal of information when ‘persistence causes injury’ even if the original articles were lawfully published. While privacy law in Mexico contains exceptions if the information is in the public interest, these exceptions were not applied in the judgment. The decision required that Google remove the results on its national site for Mexico.”64 In other words, the court deemed that de la Peña’s concerns overruled Google’s right to index Fortuna’s content, deeming it incompatible with the public interest.

According to the Mexican human rights organization R3D, which fought and appealed the case to the Seventh Circuit Court of the Auxiliary Center of the First Region, the circuit court repealed the decision of the lower court two years after its decision, rendering INAI’s resolution moot.65 Even though the repeal sets important precedent for press freedom in general, the decision will likely be appealed to a higher court. Given Mexico’s poor state of press freedom66 and high level of corruption,67 it seems inevitable that the RTBF will continue to be used as a tool by the Mexican elite to control information—further eroding press freedom and access to objective, high-quality information.

Scenario III: The RTBF is harmonized with press freedom

With effective public advocacy and oversight, education, and judicial accountability, RTBF does not need to be inherently dangerous. For instance, a case in Colombia exemplified how safeguards for press freedom can complement RTBF legislation. Like Hong Kong, Colombia does not have formal RTBF legislation; however, its legal precedent regarding the RTBF stems from a 2015 case in which the petitioner argued that information published by the newspaper El Tiempo had tarnished their reputation, damaged their name, and violated their privacy. The article in question stated that the citizen participated in an alleged crime for which they had already been acquitted. The lawsuit also sought action against Google since the inaccurate information appeared when conducting a Google search of the individual’s name. In a positive move, the court noted the serious nature of crime and the potentially severe consequences to the individual of sharing the information, and it decided to grant the action protecting the petitioner’s rights. Yet, it also decided that the newspaper was not required to remove the article, but was required to update the published story with more accurate information and clarify “the situation regarding the plaintiff with respect to the criminal accusations under dispute.”68

With regards to Google—and in contrast to the Google Spain ruling by the CJEU—the court found that an individual has the right to ask that specific links to web pages that have outdated information about the individual be made inaccessible. However, the court also found that internet intermediaries were not liable for content where third parties inflicted damage to fundamental rights, so it decided to acquit Google of all responsibility on the grounds of protecting freedom of expression due to its role as an intermediary. Instead, “The court imposed the obligation to de-list the pages from search engines on the original publisher—in this case, the newspaper—rather than the search engines themselves. The newspaper was ordered to use technical measures to prevent indexing of content by Google and ensure that search engines would not list the pages.”69

The court also identified that the case had the potential to jeopardize freedom of expression of a media outlet, and applied the Inter-American Court of Human Rights’ “permissible limitation test” to assess its potential impact.70

This will likely only grow in relevance since Latin America has varying interpretations of the RTBF.71 Overall, the case in Colombia struck a relatively fair deal between concerns for press freedom on the one hand, and the understandable desire for reasonable privacy protections and accurate information online on the other.

Conclusion

In the age of big data, people’s pasts are increasingly influencing their presents and futures; private companies know individuals better than they know themselves, and governments can track and monitor people without their even knowing. Protecting privacy in the modern world is a constant struggle, and in many parts of the world, the right to speak one’s mind is as well. As such, the RTBF has serious and legitimate implications on freedom of expression, and poses a clear threat to press freedom around the world. The RTBF has the potential to undermine the achievements made concerning media development globally, notably enabling access to objective, high-quality information, and the challenges to media development it imposes will likely only be exacerbated over time as RTBF polices are adopted more broadly beyond Europe and outside the constraints of robust democratic oversight, transparency, accountability, and a host of other necessary principles.

The conflict between governments and the private sector is likely to intensify—pitting human rights and journalism against the will of political leaders and the tacit enforcement of internet intermediaries. Regardless of how the environment changes, the RTBF raises a critical point relevant to the future of the digital societies being created: if information is removed or deleted, or if the ability to access information is stymied, journalism is fundamentally undermined. As the RTBF continues to evolve across contexts, it will undoubtedly empower those seeking to control information, while making the objectives of the media development community harder to achieve. Therefore, the media development community has a responsibility to engage in the debates, raise awareness of how the RTBF is endangering press freedom, and ensure that the tireless work and progress achieved is not undermined by unscrupulous actors vying to make information inaccessible.

Want more on the so-called Right to be Forgotten? Read Michael’s follow-up post “Reflection on the ‘Right to be Forgotten’ and the Role of the Media” to find out more about the issue and learn ways for media development stakeholders to get engaged in conversations about this and other key internet governance concerns.

Footnotes

- A. Mantelero, “The EU Proposal for a General Data Protection Regulation and the Roots of the ‘Right to Be Forgotten,’” Computer Law & Security Review, 29(3), 2013: 229-235, http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0267364913000654?via%3Dihub, described it in the following way: “The issue has arisen from desires of individuals to ‘determine the development of their life in an autonomous way, without being perpetually or periodically stigmatized as a consequence of a specific action performed in the past.’” Another definition was offered by the international freedom of expression advocacy organization IFEX: “The ‘right to be forgotten’ can be defined in three ways: i) a term based on the right to access, modify, and remove our personal information held in databases that are not under our control; ii) an express obligation to eliminate financial or criminal data after a specific time period has lapsed; iii) the removal of information from search engine results, in which case the information is not eliminated but simply will not appear as an outcome of a search.” See: “What Are the Implications of the Right to Be Forgotten in the Americas?” IFEX, September 22, 2015, https://www.ifex.org/americas/2015/09/22/derecho_olvido/ and G. Brock, The Right to Be Forgotten: Privacy and the Media in the Digital Age, (London, UK: I. B. Tauris, 2016), http://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/publication/right-be-forgotten-privacy-and-media-digital-age.

- Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, http://www.ohchr.org/EN/UDHR/Documents/UDHR_Translations/eng.pdf.

- Freedom House, Freedom of the Net 2017: Manipulating Social Media to Undermine Democracy, 2017, https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/freedom-net-2017; Freedom House, Freedom of the Press 2017, 2017, https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-press/freedom-press-2017; D. Kaye, Promotion and Protection of the Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression (A/71/373), United Nation, 2016, http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/71/373.

- Courtney Radsch, “Journalists in Peril around the Globe as US Cedes Leadership Role,” the Hill, August 19, 2017, http://thehill.com/blogs/pundits-blog/media/347143-journalists-in-peril-as-us-cedes-leadership-role; Tara Nissl, “Indonesia Urged to Address Press Freedom Violations in West Papua,” International Press Institute, December 7, 2016, https://ipi.media/indonesia-urged-to-address-press-freedom-violations-in-west-papua/.

- “#KeepItOn,” Access Now, https://www.accessnow.org/keepiton/.

- Caro Rolando, How “The Right to Be Forgotten” Affects Privacy and Free Expression,” IFEX, July 21, 2014, https://www.ifex.org/europe_central_asia/2014/07/21/right_forgotten/.

- And from larger internet governance debates and processes in general. See C. Cath, N. Ten Oever, and D. O’Maley, Media Development in the Digital Age: Five Ways to Engage in Internet Governance, Center for International Media Assistance, 2017, https://www.cima.ned.org/publication/media-capture-in-the-service-of-power/.

- Kashmir Hill, “How Facebook Figures Out Everyone You’ve Ever Met,” Gizmodo, November 7, 2017, https://gizmodo.com/how-facebook-figures-out-everyone-youve-ever-met-1819822691.

- Christopher Titze, “How ‘Right to Be Forgotten’ Puts Privacy and Free Speech on a Collision Course,” The Conversation, November 18, 2016, https://theconversation.com/how-right-to-be-forgotten-puts-privacy-and-free-speech-on-a-collision-course-68997.

- Reporters Without Borders and advocacy organization La Quadrature du Net jointly drafted a paper that identifies points of concern and makes relevant recommendations “designed to reconcile the right to privacy with freedom of expression in a reasonable manner under the aegis of the courts and not the private sector or government agencies.” See “Recommendations on the Right to Be Forgotten by La Quadrature du Net and Reporters Without Borders,” Reporters Without Borders, September 26, 2014, https://rsf.org/en/news/recommendations-right-be-forgotten-la-quadrature-du-net-and-reporters-without-borders.

- This is especially relevant vis-à-vis memory and the creation of historical narratives. For more information, see N. Tirosh, “Reconsidering the ‘Right to Be Forgotten:’ Memory Rights and the Right to Memory in the New Media Era.” Media, Culture, & Society, 39(5), 2017: 644-660, http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0163443716674361#articleCitationDownloadContainer.

- Nick Routley, “Error 404: A Look at Digital Decay,” Visual Capitalist, August 7, 2017, http://www.visualcapitalist.com/digital-decay/.

- Ibid.

- For overviews of the history of the RTBF, see A. De Baets, “A Historian’s View on the Right to Be Forgotten,” International Review of Law, Computers, & Technology, 30(1-2), 2016: 57-66, http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13600869.2015.1125155; H. Miyashita, The ‘Right to Be Forgotten

- Athalie Matthews, “How Italian Courts Used the Right to Be Forgotten to Put an Expiry Date on News,” the Guardian, September 20, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/media/2016/sep/20/how-italian-courts-used-the-right-to-be-forgotten-to-put-an-expiry-date-on-news.

- J. Rosen, “Response: The Right to Be Forgotten,” Stanford Law Review, 2012, https://www.stanfordlawreview.org/online/privacy-paradox-the-right-to-be-forgotten/.

- Not to be confused with the European Court of Justice, which is one of the two principal bodies of the CJEU.

- C-131/12 Google Spain SL, Google Inc. v. Agencia Española de Protección de Datos (AEPD) and Mario Costeja González judgment available at “Judgment of the Court (Grand Chamber,” Court of Justice of the European Union, http://curia.europa.eu/juris/document/document_print.jsf?doclang=EN&docid=152065. For additional information about the case, see this overview: “The Right to Be Forgotten (Google v. Spain),” Electronic Privacy Information Center, https://epic.org/privacy/right-to-be-forgotten/.

- Alan Travis and Charles Arthur, “EU Court Backs ‘Right to Be Forgotten’: Google Must Amend Results on Request,” the Guardian, May 13, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2014/may/13/right-to-be-forgotten-eu-court-google-search-results.

- European Commission, “Factsheet on the ‘Right to Be Forgotten’ Ruling (C-131/12),” http://ec.europa.eu/justice/data-protection/files/factsheets/factsheet_data_protection_en.pdf.

- Agencia Española de Protección de Datos.

- J.-M. Chenou and R. Radu, “The ‘Right to Be Forgotten’: Negotiating Public and Private Ordering in the European Union,” Business & Society, 2017, 1-29, http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0007650317717720. The authors also provide an excellent overview of the case and its effects on content regulation and intermediary liability.

- M. Horten, ‘Content Responsibility’: The Looming Cloud of Uncertainty for Internet Intermediaries, Center for Democracy and Technology, 2016, https://cdt.org/files/2016/09/2016-09-02-Content-Responsibility-FN1-w-pgenbs.pdf. For more information, see Tarra Wadhwa and Gabriel Ng, “Tech Companies Policing the Web Will Do More Harm than Good,” Wired, July 31, 2017, https://www.wired.com/story/tech-companies-policing-the-web-will-do-more-harm-than-good/ and Christopher Kuner, “The Internet and the Global Reach of EU Law,” The London School of Econonomics and Political Science, July 18, 2017, http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/businessreview/2017/07/18/the-internet-and-the-global-reach-of-eu-law/.

- It is worth noting that by pressing this case and effectively making himself a legal guinea pig, González ironically thrust himself into the spotlight, which further highlighted the information he did not want the world to know about—known as the “Streisand effect.” See M. Xue, G. Magno, E. Cunha, V. Almeida, and K. W. Ross, “The Right to Be Forgotten in the Media: A Data-Driven Study,” Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technologies, (4), 2016: 1-14. https://engineering.nyu.edu/files/RTBF_Data_Study.pdf. This was highlighted by the Guardian (James Ball, “Costeja González and a Memorable Fight for the ‘Right to Be Forgotten,’” May 14, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/world/blog/2014/may/14/mario-costeja-gonzalez-fight-right-forgotten) as well as British comedian John Oliver on his HBO show Last Week Tonight (“Right To Be Forgotten: Last Week Tonight with John Oliver (HBO),” YouTube, posted by LastWeekTonight, May 19, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r-ERajkMXw0).

- “Directive 95/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 October 1995 on the Protection of Individuals with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data,” Official Journal L 281 , 23/11/1995 P. 0031 – 0050, Access to European Union Law, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:31995L0046:en:HTML.

- This also reflects principles from the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (2000), specifically articles 7 and 8, Access to European Union Law, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:12012P/TXT.

- J.-M. Chenou and R. Radu, “The ‘Right to Be Forgotten’: Negotiating Public and Private Ordering in the European Union,” Business & Society, 2017, 1-29, http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0007650317717720. The authors also underscored that the decision by the CJEU about the RTBF allows search engines to exercise discretionary power in the interpretation of the law without establishing clear implementation procedures.

- Anyone can request to have links de-indexed by filling out this form: “Request Removal of Content Indexed on Google Search Based on Data Protection law in Europe,” Google, https://www.google.com/webmasters/tools/legal-removal-request?complaint_type=rtbf&pli=1.

- For an in-depth analysis of the relationship between the GDPR and the RTBF, see Mantelero, “The EU Proposal for a General Data Protection Regulation and the Roots of the ‘Right to Be Forgotten.’” Also see Kuner, “The Internet and the Global Reach of EU Law,” and Eugenio Foco, “The Codification of the Right to Be Forgotten in the Digital Era: From Directive 95/46/EC to the General Data Protection Regulation,” Media Laws, November 17, 2016, http://www.medialaws.eu/the-codification-of-the-right-to-be-forgotten-in-the-digital-era-from-directive-9546ec-to-the-general-data-protection-regulation/.

- General Data Protection Regulation, “Art. 17 GDPR Right to Erasure (‘Right to Be Forgotten’),” https://gdpr-info.eu/art-17-gdpr/. For more information regarding how it relates to press freedom, see Daphne Keller, “The New, Worse ‘Right to Be Forgotten,’” Politico, January 27, 2016, http://www.politico.eu/article/right-to-be-forgotten-google-defense-data-protection-privacy/ and Jean-Paul Marthoz, “EU Rulings on Whistleblowers and Right-to-Be-Forgotten Laws Puts Press freedom at Risk,” Committee to Protect Journalists, April 14, 2016, https://cpj.org/blog/2016/04/eu-rulings-on-whistleblowers-and-right-to-be-forgo.php.

- “WAN-IFRA Report on Right to Be Forgotten: The Myths, the Facts and the Future,” World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers, April 15, 2016, https://blog.wan-ifra.org/2016/04/15/wan-ifra-report-on-right-to-be-forgotten-the-myths-the-facts-and-the-future.

- European Commission, “Factsheet on the ‘Right to Be Forgotten’ Ruling (C-131/12).”

- Peter Fleischer, “Adapting Our Approach to the European Right to Be Forgotten,” Google, March 4, 2016, https://www.blog.google/topics/google-europe/adapting-our-approach-to-european-rig/.

- According to Reuters, Google had “only scrubbed results across its European websites, such as Google.de in Germany and Google.fr in France, on the grounds that to do otherwise would have a chilling effect on the free flow of information.” See Julia Fioretti, “France Fines Google over ‘Right to Be Forgotten,’” Reuters, March 24, 2016, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-google-france-privacy/france-fines-google-over-right-to-be-forgotten-idUSKCN0WQ1WX.

- For examples, see Alex Hern, “ECJ to Rule on whether ‘Right to Be Forgotten’ Can Stretch beyond EU,” the Guardian, July 20, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/jul/20/ecj-ruling-google-right-to-be-forgotten-beyond-eu-france-data-removed and “French Court Refers ‘Right to Be Forgotten’ Dispute to Top EU Court,” Reuters, July 19, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-google-litigation/french-court-refers-right-to-be-forgotten-dispute-to-top-eu-court-idUSKBN1A41AS. For more information regarding Google’s response, see Peter Fleischer, “Reflecting on the Right to Be Forgotten,” Google, December 9, 2016, https://www.blog.google/topics/google-europe/reflecting-right-be-forgotten/. In response, a coalition of 29 media organizations led by the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press issued a brief in support of Google, arguing that the French authorities have no right to “force their interests on Internet users in other countries, and allowing such worldwide restrictions in the interest of enforcing domestic law would lead many other countries to try to restrict Internet access.” See “Google v. CNIL,” Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, November 4, 2016, https://www.rcfp.org/browse-media-law-resources/briefs-comments/google-v-cnil.

- See paragraphs 76-88 of the ruling.

- See paragraph 93 of the ruling.

- See paragraph 85 of the ruling. Additionally, there are reasons why some people may not want to submit RTBF requests or “be forgotten” online, for instance, as outlined in Markou (2015). For more information, see Emma Woollacott, “Five Reasons Not to Invoke Your Right to Be Forgotten,” Forbes, June 6, 2014, https://www.forbes.com/sites/emmawoollacott/2014/06/06/five-reasons-not-to-invoke-your-right-to-be-forgotten/#53897d385cd3.

- European Commission, “Factsheet on the ‘Right to Be Forgotten’ Ruling (C-131/12).”

- Christopher Titze, “How ‘Right to Be Forgotten’ Puts Privacy and Free Speech on a Collision Course,” The Conversation, November 18, 2016, https://theconversation.com/how-right-to-be-forgotten-puts-privacy-and-free-speech-on-a-collision-course-68997. For more information, see G. Brock, The Right to Be Forgotten: Privacy and the Media in the Digital Age, (London, UK: I. B. Tauris, 2016), http://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/publication/right-be-forgotten-privacy-and-media-digital-age.

- Athalie Matthews, “How Italian Courts Used the Right to Be Forgotten to Put an Expiry Date on News,” the Guardian, September 20, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/media/2016/sep/20/how-italian-courts-used-the-right-to-be-forgotten-to-put-an-expiry-date-on-news.

- M. Weston, The Right to Be Forgotten: Analyzing Conflicts between Free Expression and Privacy Rights, published master’s thesis: Brigham Young University, 2017, http://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=7453&context=etd. Also see Alan Hope, “’Right to Be Forgotten’ Extends to Newspaper Archives,” Flanders Today, May 25, 2016, http://www.flanderstoday.eu/business/right-be-forgotten-extends-newspaper-archives.

- “Government Requests to Remove Content,” Google, https://transparencyreport.google.com/government-removals/overview.

- “We Believe Security Shouldn’t Come at the Expense of Individual Privacy,” Apple, https://www.apple.com/lae/privacy/government-information-requests/.

- Facebook, Government Requests Report, https://govtrequests.facebook.com/.

- “Removal Requests,” Twitter, https://transparency.twitter.com/en/removal-requests.html.

- The transparency requests are also a partial response to civil society groups. For more information, see “Open Letter to Google Advisory Council,” Access Now, https://www.accessnow.org/cms/assets/uploads/archive/docs/Open_Letter_to_Google_Advisory_Council.pdf.

- https://transparencyreport.google.com/government-removals/overview.

- A URL is the full link to a website, such as https://www.website.com. For more information, see “What Is a URL?” Oracle, https://docs.oracle.com/javase/tutorial/networking/urls/definition.html.

- Nick Wells, “Google’s Two Years of Forgetting Europeans,” CNBC, May 27, 2016, https://www.cnbc.com/2016/05/27/googles-two-years-of-forgetting-europeans.html. For the complete report, see “Search Removals under European Privacy Law,” Google, https://transparencyreport.google.com/eu-privacy/overview. And in case more detailed information is not available in the various transparency reports, the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University maintains an extensive online database that indexes cease and desist letters concerning online content: “Lumen,” Lumen Database, https://lumendatabase.org/.

- Danny O’brien and Jillian C. York, “Rights that Are Being Forgotten: Google, the ECJ, and Free Expression,” Electronic Frontier Foundation, July 8, 2014, https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2014/07/rights-are-being-forgotten-google-ecj-and-free-expression.

- J. Bárd and J. Bayer, A Comparative Analysis of Media Freedom and Pluralism in the EU Member States, European Commission Directorate General for Internal Policies, Policy Department C: Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs – Civil Liberties, Justice, and Home Affairs, 2016, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2016/571376/IPOL_STU(2016)571376_EN.pdf. Also see Lauren C. Williams, “What Does the EU’s New ‘Right to Be Forgotten’ Mean for Free Speech?” Think Progress, May 13, 2014, https://thinkprogress.org/what-does-the-eus-new-right-to-be-forgotten-mean-for-free-speech-309d3c7a779e/.

- ARTICLE 19, The ‘Right to Be Forgotten’: Remembering Freedom of Expression, 2016, https://www.article19.org/data/files/The_right_to_be_forgotten_A5_EHH_HYPERLINKS.pdf.

- Moroğlu Arseven, “Turkish Constitutional Court: Right to Be Forgotten Trumps Press Freedom for Fourteen Year Old News about an Individual’s Drug Use,” Lexology, September 6, 2016, https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=f0932e7d-1ea2-44b4-9ac9-f18cbe66c703 and Burcu Tuzcu Ersin, LL.M., A. Ülkü Solak, and Yonca Çelebi, “Turkey: Turkish Constitutional Court: Right to Be Forgotten Trumps Press Freedom for Fourteen Year Old News about an Individual’s Drug Use,” Mondaq, last updated September 8, 2016, http://www.mondaq.com/turkey/x/525452/Data+Protection+Privacy/Turkish+Constitutional+Court+Right+To+Be+Forgotten+Trumps+Press+Freedom+For+Fourteen+Year+Old+News+About+An+Individuals+Drug+Use.

- Argentina being a notable example—see Vinod Sreeharsha, “Google and Yahoo Win Appeal in Argentine Case,” New York Times, August 19, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/20/technology/internet/20google.html?_r=0. Another source for this is an article written in 2012 for National Public Radio where, even two years before the CJEU’s ruling was handed down, the author suggested the RTBF is the biggest threat to free speech on the internet: Robert Krulwich, “Is the ‘Right to Be Forgotten’ the ‘Biggest Threat to Free Speech on the Internet?’” February 24, 2012, http://www.npr.org/sections/krulwich/2012/02/23/147289169/is-the-right-to-be-forgotten-the-biggest-threat-to-free-speech-on-the-internet.

- “The Ordinance at a Glance,” Privacy Commissioner for Personal Data, Hong Kong, https://www.pcpd.org.hk/english/data_privacy_law/ordinance_at_a_Glance/ordinance.html.

- Hogan Lovells, A Right to Be Forgotten in Hong Kong?, August 2015, http://www.hoganlovells.com/files/Uploads/Documents/Newsflash_A_Right_to_be_Forgotten_in_Hong_Kong_HKGLIB01_1452118.pdf.

- International Federation of Libraries, Background: The Right to Be Forgotten in National and Regional Contexts, 2016, https://www.ifla.org/files/assets/clm/statements/rtbf_background.pdf and “The Ordinance at a Glance,” Privacy Commissioner for Personal Data, Hong Kong, https://www.pcpd.org.hk/english/data_privacy_law/ordinance_at_a_Glance/ordinance.html.

- Access Now, Access Now Position Paper: Understanding the ‘Right to Be Forgotten’ Globally and International Federation of Libraries, Background: The Right to Be Forgotten in National and Regional Contexts.

- “Hong Kong Residents Protest for Democracy as China Tightens Grip,” CBS This Morning, July 1, 2017, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/hong-kong-protests-20th-anniversary-britain-handover-freedoms-slipping/.

- Freedom House, Freedom of the Press 2017.

- Diario Oficial de la Federación, Reglamento de la Ley Federal de Protección de Datos Personales en Posesión de los Particulares (LFPDPPP), http://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5226005&fecha=21/12/2011.

- For more information, see Juan Luis Hernández Conde, ‘Can You Be Forgotten in Mexico,’ The Tech Law’s Den, February 19, 2016, https://hernandezconde.wordpress.com/2016/02/19/can-you-be-forgotten-in-mexico-what-is-the-right-to-be-forgotten-anyway/.

- Freedom House, “Mexico Country Profile,” Freedom on the Press 2017, 2017, https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-press/2017/mexico and International Federation of Libraries, Background: The Right to Be Forgotten in National and Regional Contexts.

- Freedom House, “Mexico Country Profile” and “¡Ganamos! Tribunal Anula Resolución del INAI Sobre el Falso ‘Derecho al Olvido,’” R3D, August 24, 2016, https://r3d.mx/2016/08/24/amparo-inai-derecho-olvido/.

- Freedom House, “Mexico Country Profile.”

- Transparency International, Corruption Perceptions Index 2016, 2016, http://files.transparency.org/content/download/2089/13368/file/2016_CPIReport_EN.pdf.

- Access Now, Access Now Position Paper: Understanding the ‘Right to Be Forgotten’ Globally.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., International Federation of Libraries, Background: The Right to Be Forgotten in National and Regional Contexts, and “Martínez v. Google,” Global Freedom of Expression, Columbia University, https://globalfreedomofexpression.columbia.edu/cases/martinez-v-google/.

- For instance, a Brazilian judge stressed in November 2017 that the “right to oblivion is not a form of censorship,” and it can exist without “impeding publication” by the press. See Letícia Casado, “Para Ministro do STJ, Direito ao Esquecimento É Diferente de Censura,” Poder, November 7, 2017, http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/poder/2017/11/1933401-para-ministro-do-stj-direito-ao-esquecimento-e-diferente-de-censura.shtml.