Introduction

Online publishers now know more about their audiences than ever before. When you visit a digital-savvy news site, they will likely glean your age group, location, what device you are using, how long you visit, and how loyal you are to the site, among other data that are both important to their advertisers and allow them to better tailor their content and delivery strategies to your preferences.

Still, there is one gaping hole in today’s data: even the most advanced analytics firms are unable to track how that audience landed on the page to begin with up to 20 percent of the time. If you clicked on a link shared on Facebook or Twitter, the news site will detect that. If you found a story through a Google or Bing search, the site will know. And if you typed the URL directly into the browser, that too will be recorded.

The blind spot, dubbed “dark social,” originates when visitors arrive from links shared by email, text, or private messaging applications—not to be confused with the more nefarious “dark web.” As analytics firms begin to shine a light onto the dark spots of referral data, they are learning that these invisible, peer-to-peer forms of sharing news are far more important than previously understood, kindling further consideration among publishers of how to harness messaging platforms such as WhatsApp and Telegram for distribution.

One analytics firm, Chartbeat, has been a pioneer in helping websites better track private forms of content sharing. According to lead data scientist Chris Breaux, “When we look at our referrer traffic over our entire network, the number one source is still direct traffic. Number two is Google search, and number three is this dark social bucket.”1

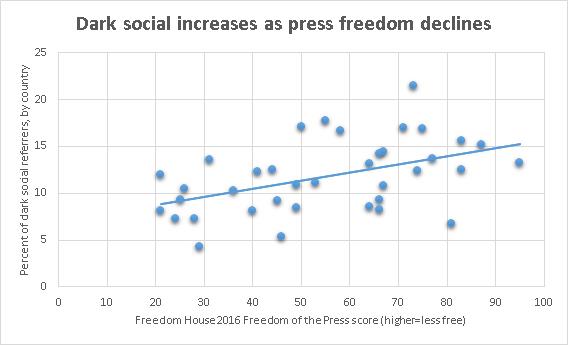

This report finds that in some of the world’s most repressive media environments, dark social might be playing an even greater role. A CIMA analysis of data obtained from Chartbeat suggests that in such environments, citizens are gravitating away from Facebook, Twitter, and other public platforms and toward channels perceived to be more secure and private when sharing and discussing news. While publishers everywhere need to find distribution strategies that work well with dark social forms of sharing, independent news publishers working in oppressive environments might have an even larger incentive.

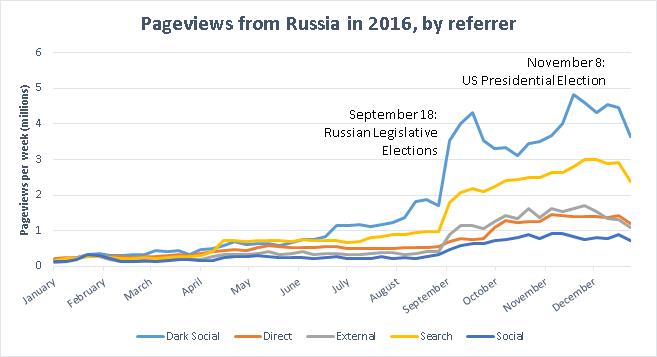

CIMA’s analysis of audience data from nearly 40 countries yields a statistically significant correlation between freedom of the press and reliance on dark social sharing: the more repressive the media environment, the more likely the audience is to access news through dark social. Even more illustrative of this trend, however, are some of the data points where that correlation seems the strongest, as in Turkey and Russia. In these cases, delving into incidents over the timeframe of the dataset, 2016, strongly suggests causation. Where independent news coverage is under attack, there are inevitably reverberations in how that news is accessed and shared.

Data provided by Chartbeat exhibits a statistically significant correlation between press freedom and audiences accessing news via dark social channels. Each point above denotes a country in the data sample, according to the average percent of dark social referrals for that audience over the course of 2016.

Defining and Tracking Dark Social

Data analytics today means far more than a simple count of subscribers, with services ranging from free snapshots like Facebook Insights and Google Analytics to tailor-made analysis and market strategies from private firms. One essential piece of information from these services is the “referrer,” which identifies the site or platform first used to access the page. As emphasized in a recent CIMA report,2 the global dominance of Google search and Facebook as referrers has been a cause of some concern, particularly for small media outlets that are especially vulnerable to a sudden and dramatic decline in traffic when these platforms make changes to the way they prioritize or organize content.

Relatively less attention, however, has been given to the implications of dark social, precisely because of its nature: dark social refers to online and digital sharing either missing or incorrectly attributed in site traffic analytics. Unlike other referrers, these lack the usual “tag” denoting the origins of the click. Depending on the analytics tool, they may even be read as direct traffic, assuming that the lack of tag means a user manually entered the full URL—an increasingly unlikely explanation as web addresses stretch from something like cima.ned.org to https://www.cima.ned.org/publication/media-feast-news-famine-ten-global-advertising-trends-threaten-independent-journalism/.

But following a 2012 Atlantic article3 by Alexis Madrigal, it became clear that dark social is not just a matter of missing data, but of missed opportunities. Marketing firms have since raced to capitalize4 on the conversation, offering solutions for more detailed analytics and strategies to convert these viewers into paying consumers. That which dark social describes—basic person-to-person sharing—is far from new, but only in the past few years has anyone been able to systematically identify and track it.

Leading the way in identifying dark social and other traffic referrers, Chartbeat continues to refine its approach, with updates put in place as recently as September 2017. With each round, traffic previously considered “dark” drops, newly identified as one of myriad possible explanations. Nonetheless, dark social remains in many cases a more frequent referrer than social sites like Facebook and Twitter. For all of the time and resources spent on platform giants like Facebook and Google, running content and battling opaque algorithms, bypassing audiences from dark social is an oversight many can no longer afford.

Running the Numbers

Catering to a network of roughly 50,000 news media sites, New York–based analytics firm Chartbeat has compiled vast amounts of audience data, tracking where online news readership is going, where it is coming from, and how. While that data cover a wide breadth of sources, the majority are larger English-language Western news sites and globally trusted outlets.5

To unpack some of this data, CIMA analyzed audience insights from 37 countries, representing a variety of geographic regions, income per capita, population sizes, and levels of press freedom. The data set, recording total pageviews to Chartbeat’s network of news sites, provides a week-by-week look at country of origin, what device was used to access the site, platform or referrer, and engaged time on the page, and how these data compare from country to country over the course of 2016.

The sheer breadth of information available presents any number of possibilities for closer study—a snapshot of questions news sites must ask when analyzing their own data. When do online audiences in country x access news from this selection of major Western outlets, and how? Inevitably, contextualizing the data is of primary concern. Given that, sweeping general trends are rare and changeable. Dark social, however, is a significant player across the board, and one largely overlooked. While CIMA anticipates continued applications of this trove of data, it is vital in every case to first recognize where the audiences are coming from and how best to reach them when they need it most.

Turkey: Post-Coup Crackdowns Push Citizens to Dark Social Platforms

On July 15, 2016, viewers around the globe watched tanks rolling across Istanbul’s Bosphorus Bridge as an attempted coup d’état unfolded, but the fraught night that ensued proved to be just the beginning of a much longer, brutal government crackdown. As state-owned TRT news announced that the military had “completely taken over the administration of the country to reinstate constitutional order,” President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, speaking via Facetime and on CNN Türk, called upon the public to take to the streets. Just hours later, CNN Türk was itself occupied by the military, anchors leaving their desks mid-air as the station went quiet. Bolstered by loyal police and armed forces, alongside pro-government demonstrations, Erdoğan soon succeeded in repelling the coup attempt, reclaiming his authority with a vengeance. A massive crackdown followed, engulfing independent media in the country.

Erdoğan and his administration targeted not only news and media outlets, many of which were already ensnared in a toxic and captured media environment,6 but citizens active on social media. While estimates vary, one report found that more than 110,000 people were detained within nine months of the coup attempt, thousands under investigation for social media postings. Frequent among those charges are insulting the president, opposing the anti-terror law, and spreading hatred or propaganda. To further silence dissent, the Turkish government is known to periodically “throttle,” or block, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and WhatsApp—so much so that one site has dedicated itself entirely to tracking the blackouts. While such censorship, both self- and government-imposed, has steeply increased since the July 2016 coup attempt, it is far from new. Access to social media appeared to be restricted following the June 2016 bombing at Atatrk Airport, for instance, and a wider blackout was imposed later in the year as unrest continued.

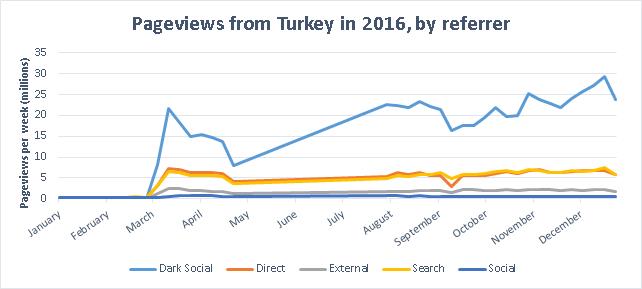

The combined crackdown on legacy news outlets and major social media platforms in Turkey seems to have pushed citizens to seek and share information elsewhere, particularly by WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger, though also on other messaging platforms like Signal and BiP Messenger, email, SMS (short message service), and of course by word of mouth. According to one source, use of WhatsApp in Turkey outranks Facebook entirely—part of a broader trend reflected in Chartbeat’s 2016 data of Turkish citizens moving away from public social platforms.

Note: Data provided by Chartbeat shows discrepancies for the months of January through February and May through July; lines of best fit demonstrate overall growth during that time period based on existing data for 2016.

While the data coming out of Turkey exhibit a notable gap in the middle of the year (fitting, given the ongoing turmoil and blackouts at the time), the pattern is clear: private, dark social sharing of and access to these major news sites outstripped even search and direct, typically the most common referrers.

What’s more, users accessed the news sites by desktop more frequently than by mobile device, unusual in a world increasingly turning to mobile, and a sign that dark social sharing may not be due strictly to the growing use of mobile messenger apps. That Turkish citizens have turned to dark social sharing techniques on desktops suggests even more strongly that they were purposefully seeking a trusted and safe environment7 to access and share news.

Yet, in the midst of such a thorough crackdown, even these platforms are not necessarily accessible or safe. Throttling of Facebook inevitably subsumes Facebook Messenger as well, and while WhatsApp eluded the early blackouts of Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, both it and Skype joined the list of compromised platforms by the end of the year. A massive crackdown on the lesser known messaging app ByLock sparked further concerns, as Turkish authorities overrode weak security features to trace thousands of users suspected of ties to the failed coup. Though members of thegroup had stopped using the app months before, realizing that it was compromised, authorities reportedly arrested up to 75,000 suspects primarily because they had downloaded the app. While other platforms, like Signal and Telegram, are notably more secure options, the ByLock crackdown was a chilling reminder that the movement of citizens to dark social is not always a move towards greater safety, and particularly under a government as sophisticated as Turkey’s.

Russia: A Shrinking Space for Independent Voices

Press freedom trackers exhibit serious concern about the deteriorating state of the Russian media environment, continually classified as “not free.”8 While some have suggested the state is learning from the Chinese approach to online censorship, limitations on press freedom and freedom of expression in Russia are far from new—independent voices in the country have been systematically dismantled or overruled since President Vladimir Putin first came to power in 2000. Passed in the broader context of the global “War on Terror,” a 2002 anti-terror law targets “speech, publications, groups, and ideas deemed ‘extremist,’ a broadly defined notion interpreted subjectively by officials.”9 The Russian Criminal Code additionally inhibits a vague “incitement to hatred or hostility,” while the 2010 Law on Protection of Children from Information Harmful to Their Health and Development instills the government line from an early age. Even the church is not safe from the battleground of freedom of expression, highlighted in the notorious Pussy Riot case of 2012 as three members of a Russian punk rock band were jailed on charges of hooliganism for performing a song critical of Putin in a Moscow cathedral.

At the time of this data collection in 2016, journalists were attacked while covering human rights abuses in the North Caucasus, security forces raided the homes of Crimean journalists, one journalist was tried after alleging election irregularities in September, another detained on suspicion of espionage in October, and in December, a blogger was jailed for “publicly justifying terrorism” after criticizing Russian military actions in Syria. The list goes on. In this chilling environment, Russians too have begun to show a preference for platforms that seem more private or secure—all the more so, most likely, for coverage or websites that may be deemed opposition by the Russian government.10

For Russian audiences, as in Turkey, pageviews from social platforms remain the lowest-performing referrers. As seen above, direct views are also somewhat low, suggesting that this audience is not comprised of regular visitors. Instead, these are audiences actively seeking out (search) and sharing (dark social) news media. Late 2016 provided any number of major talking points for a Russian audience, including Russian legislative elections in mid-September, the American presidential election and following discussions in November, and international talks toward a Syrian ceasefire throughout, to name a few.

Governments already wary of the media space are often the first to catch on to the importance of dark social and private messaging—typically in a bid to restrict possible demonstrations, as political scientist Gary King finds in China,11 or to combat perceived threats from extremist messaging. But the result has placed increasing limitations on access to alternative news at all. In May 2017, the Russian communications regulator blocked Line, Blackberry, and Imo messengers, swiftly followed by WeChat, a hugely popular messaging platform owned by Chinese conglomerate Tencent. Telegram, yet another messaging platform known for its high encryption and privacy policies, narrowly escaped joining that list. It, along with WhatsApp, Viber, Skype, and others, continues to enjoy a steady Russian audience—an audience some news outlets have slowly begun to tap in to.

What does this mean for independent, digital news producers in repressive environments?

For media sites around the world battling with a rapidly changing business model, time and resources are scarce for digging through audience data and experimenting with new platforms. Both may be necessary in the evolving media environment. Unfortunately for digital news producers working in more repressive environments, observing these trends in audience data may not lead to a clear strategy. Still, digital strategists would recommend a few key steps:

- Know where your audience is and how it is most likely to engage. For news sites, that may be directly to the page or through search, not Facebook. Online news producers are painfully aware of the seemingly negative impact of Facebook’s opaque algorithm and the unquestionably negative impact of its monopolizing adspend12 —yet, time and resources are frequently poured into posting and promoting content on the platform. Posting and boosting content on social platforms can be relatively cheap, but best kept within its limited return on investment.

- Capitalize on the site’s “homepage experience.” Most loyal readers are still likely to go directly to the news site, and those loyal readers are also most likely to become paid subscribers. A readable, engaging homepage across devices serves their needs best and offers the potential for a more immediate, tangible return.

- Make stories readily sharable by providing links for social platforms and email as well as link shortening options. This both taps into the dark social potential and ensures more reliably trackable data in the future. More likely than not, those on a page are already sharing content, even if those reference points do not show themselves as clearly as social platforms do.

- Innovate with dark social platforms like WhatsApp and Telegram. Some outlets have already begun doing this. Facing the impending outages that came with Hurricane Irma in September 2017, Univision turned to WhatsApp to get necessary information to its audience on the platform they had in hand. Several media channels appealing to Russian audiences have also reported growing audiences on Telegram, reaching young viewers through public channels and regular updates on the encrypted messaging app.

Typically, these strategies apply across the board. For media houses in more repressive environments, however, one large caveat comes into play: strategies for profitable content distribution do not always align with what is safest for your audience and your outlet.

While media outlets across the globe wrestle with a rapidly changing business environment, those simultaneously battling a repressive government have even fewer resources to spare. Even as circumstances may require a push toward new, innovative platforms, few have the time and financial security to spend additional attention on audience data, let alone new platforms. This is all the more problematic as it remains unclear how those platforms could be monetized for content providers. Though recent pilot programs through WhatsApp hint at possible opportunities to come, for now, such digital innovations are most often lauded for their indirect benefits: better serving current audiences, fostering organizational and cultural change, and facilitating a broader ecosystem of adaptation and innovation.13 All necessary goals, but difficult to press as an outlet struggles to keep the lights on.

Additionally, with global growth in mobile use and the rise of social media platforms, audiences worldwide will, out of habit, continue to share news and links on more public platforms like Facebook and Twitter. In some cases, these crowdsourced platforms and rising citizen journalism initiatives have garnered public trust even as traditional media loses it—yet, such practices could put both audiences and independent voices at risk, and potentially lead to less sharing and engagement in response to self- and government-censorship. Media outlets in repressive environments especially may therefore need to be more proactive in steering audiences toward safer platforms, inevitably drawing attention from wary governments in the meantime. No platform is impervious to the threat of government disapproval, as illustrated by the earlier example of Russia and Telegram. Still, some platforms remain more secure than others, and choosing the best fit is key for both audiences and outlets.

As that same example shows, responsibility must also lie with the platform and its ability and willingness to protect the security of its users—audiences, journalists, and media houses alike. Platforms such as WhatsApp and Telegram have become increasingly vital for sharing news when it is needed most, both peer-to-peer and distributed content, and their vast user base depends upon protecting that space.

Beyond those recommended steps for innovative outlets and wary audiences, then, is an even greater need for support from the platforms and internet governance bodies setting the rules. These players have an undeniable role in working to create safer ecosystems for distributing news, keeping these various environments in mind to simultaneously protect the audience and create business opportunities for independent news producers. Monetizing dark social may be a matter of profit and prestige for many, but it may also be a matter of survival for those dependent upon it in today’s increasingly repressive media environments.

Footnotes

- Breaux, Chris. Interview by author. New York City, October 5, 2017.

- Michelle Foster, “Media Feast, News Famine: Ten Global Advertising Trends That Threaten Independent Journalism,” (Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance, 2017), https://www.cima.ned.org/publication/media-feast-news-famine-ten-global-advertising-trends-threaten-independent-journalism/.

- Alexis C. Madrigal, “Dark Social: We Have the Whole History of the Web Wrong,” The Atlantic, October 12, 2012, https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2012/10/dark-social-we-have-the-whole-history-of-the-web-wrong/263523/.

- Radium One, “The Dark Side of Mobile Sharing,” (RadiumOne, 2016), https://radiumone.com/darksocial/.

- Though these data encompass a wide breadth of sources, they draw heavily from American and British media houses. The variety and global reach of these outlets ensure the validity of the trends analyzed here, but every digital outlet must keep its unique context and audience in mind. In countries such as Russia, where recent laws have moved to limit international media in both ownership and the outlets themselves, these sources are more likely to be perceived as opposition.

- Andrew Finkel, “Captured News Media: The Case of Turkey,” (Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance, 2015), https://www.cima.ned.org/publication/captured-news-media-turkey/.

- Brian Barrett, “Don’t Let Wikileaks Scare You Off of Signal and Other Encrypted Chat Apps,” Wired, March 7, 2017, https://www.wired.com/2017/03/wikileaks-cia-hack-signal-encrypted-chat-apps/.

- “Russia”, Freedom House, 2016, https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-press/2016/russia.

- PEN American Center, “Discourse in Danger: Attacks on Free Expression in Putin’s Russia,” (New York, NY: 2016), https://pen.org/sites/default/files/PEN_Discourse_In_Danger_Russia_web.pdf.

- Particularly over the last year, media watchers have witnessed a global tug and pull between major Western media sources and Russian state-owned outlets like RT. As of November 2017, international media in Russia can now be registered as “foreign agents” for receiving funding from abroad. Bearing that in mind, audience numbers from Russia to Chartbeat’s primarily American and British clients are notably low. Though this cannot be taken as a simple explanation for the lower numbers of Russian viewers in 2016, the nature of the sites included in the dataset inevitably plays a role in how Russian audiences that do engage with these sources access and share them.

- Gary King, Jennifer Pan, and Margaret E. Roberts, “How Censorship in China Allows Government Criticism but Silences Collective Expression,” American Political Science Review 107 (2): 1–18, https://gking.harvard.edu/publications/how-censorship-china-allows-government-criticism-silences-collective-expression.

- Julia Kollewe, “Google and Facebook Bring in One-Fifth of Global Ad Revenue,” The Guardian, May 1, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/media/2017/may/02/google-and-facebook-bring-in-one-fifth-of-global-ad-revenue.

- Alessio Cornia, Annika Sehl, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen, “Developing Digital News Projects in Private Sector Media,” (United Kingdom: Reuters Institute and University of Oxford, 2017), https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/our-research/developing-digital-news-projects-private-sector-media.