Key Findings

Widespread use of encrypted messaging apps (EMAs) in developing countries and emerging democracies has prompted news outlets in these regions to experiment with them as mechanisms for distributing the news. From news products designed specifically for sharing via EMAs to private channels used to circumvent restrictions in repressive media environments, media outlets are testing how best to use these apps to reach audiences even in the face of technical challenges, resource demands, and sometimes, political pressure.

-News outlets are turning to EMAs to reach new audiences and to bypass state censorship in authoritarian contexts.

-Many newsrooms are experimenting with monetizing EMA content, however, it is still too early to tell whether EMAs can provide a reliable revenue stream.

-Platform dependency is a big issue when it comes to using EMAs for news—policy changes can have a big impact on how news outlets interact with their audiences.

Introduction

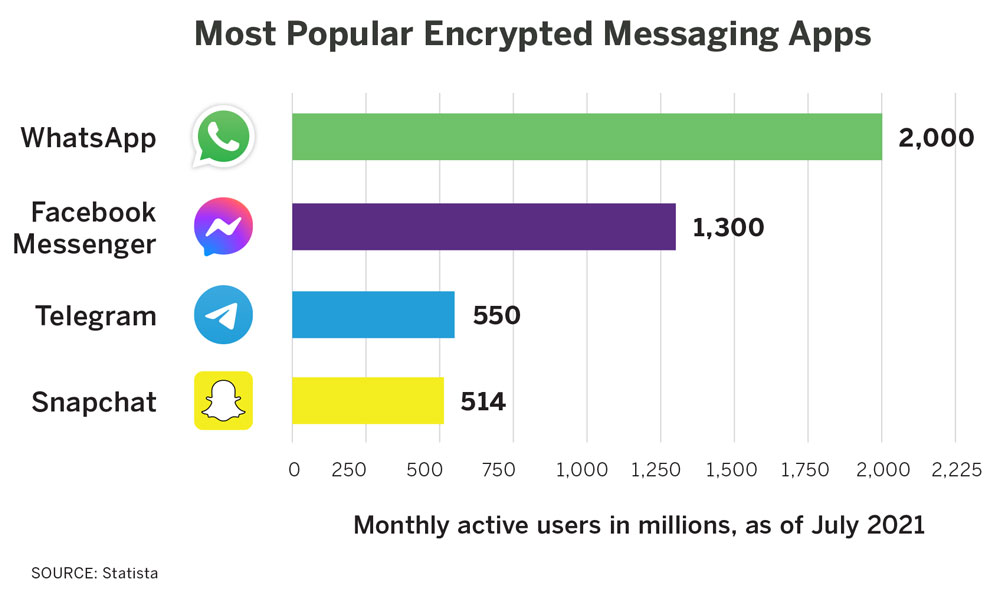

Around the world, millions of people each day use encrypted messaging apps (EMAs).1 These mobile-first applications offer end-to-end encryption to encode information and prevent messages, calls, or files from being read by anyone other than the sender or recipient. Originally designed to facilitate individual or small-group communication between friends and family, their growth in popularity over the past decade, particularly in developing countries,2 has translated into an expanded set of uses. EMAs are now used for commerce and financial transactions as well as for a variety of other purposes, such as organizing tools for political campaigns and social movements.

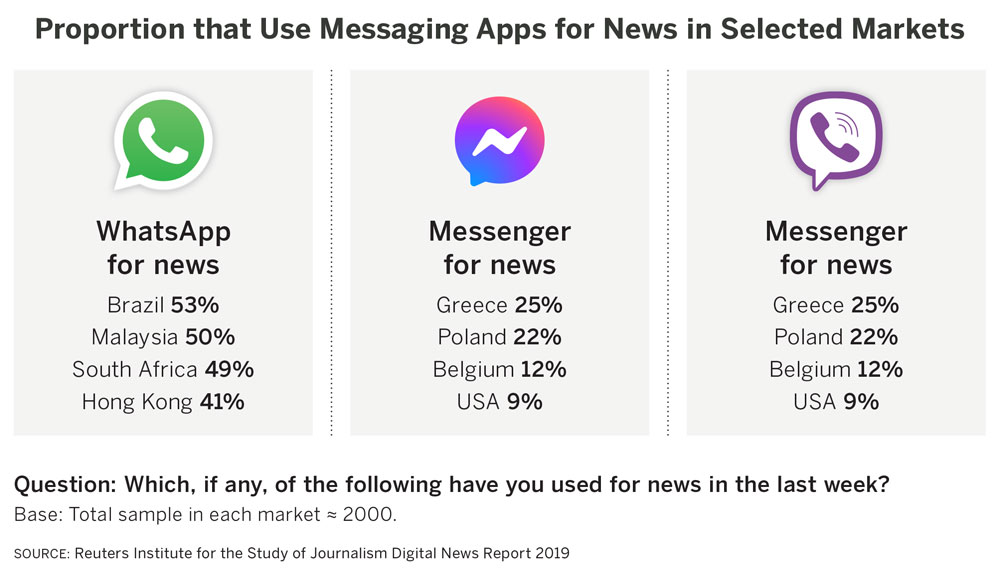

Apps such as WhatsApp, Telegram, Signal, and Viber have proven popular for several reasons. For one, in many countries, unlimited use of one or more of these applications is often included in mobile data plans, which means using them does not incur additional data charges.3 Additionally, the fact that these applications are now encrypted and users can determine who receives content provides an added level of security. This is especially important in environments with limited freedom of expression, where circulating news publicly on social media can lead to negative repercussions. In these environments, EMAs can be a way for citizens to access and share high-quality news and information more securely. This capacity is reason enough for many news outlets to develop an EMA publishing strategy.

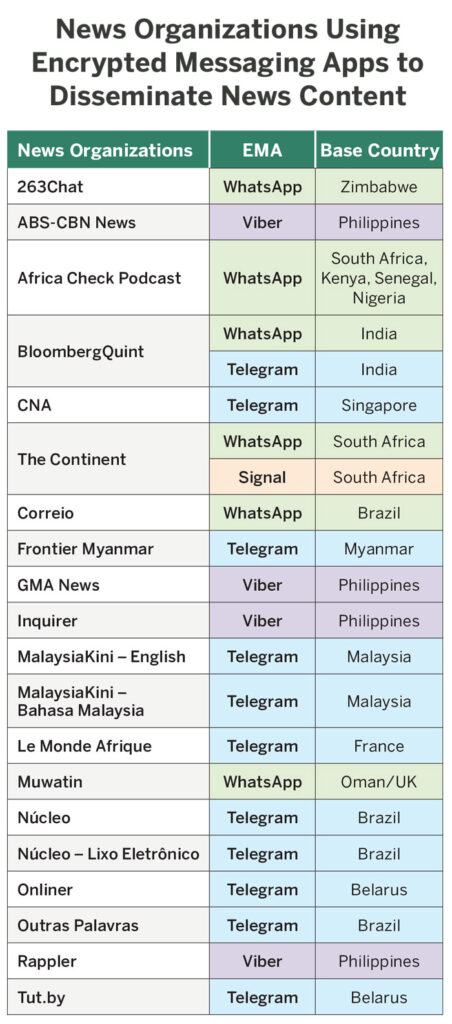

News Organizations Using Encrypted Messaging Apps to Disseminate News Content

While using EMAs for news publishing holds much potential in terms of reaching audiences, it is often not an easy proposition. Messaging apps were not designed as news distribution tools. This means outlets must overcome limitations in an application’s design, such as constraints on the number of individuals who can be sent content at one time. An individual WhatsApp group or broadcast list, for example, currently has an upper limit of 256 members. To send content to more than 256 individuals, publishers must create a new group or list once this limit is reached. There are no tools within the app to automate this process. This means newsrooms must rely on manual processes to create content for an EMA; post it to multiple groups, lists, or channels on the app; and create new groups, lists, or channels if the EMA has a limit on how many people can be sent content at one time.

Publishers are also at the mercy of the tech companies that develop the apps in terms of any changes made to the functionalities of their products or their use policies. For example, in 2020, WhatsApp introduced a new limitation to its messenger app: once a message has been forwarded more than five times, a user can only forward it to a single chat at a time.4 While this change is aimed at curbing the spread of misinformation, it also restricts the mass-forwarding of messages from news outlets.

News publishers must also contend with evolving legal frameworks governing the use of encryption. Many governments are uneasy about the widespread use of encryption tools because this prevents them from monitoring or analyzing content shared via these apps. Some countries have proposed legislation to restrict the use of encryption, which would threaten the use of EMAs for news dissemination.

There is no doubt that EMAs have revolutionized the way many people communicate and exchange information. They have also created new opportunities for independent news outlets to adapt to changing consumer habits and potentially reach new audiences. The lessons from news outlet experiments with EMAs—including what resources are required to grow and sustain these operations and how these news services might generate revenue—are important for media development actors to understand. By looking at several examples of news organizations in developing countries that have experimented with an EMA distribution strategy, its limitations and barriers emerge.

Going Where the Audience Is

Given the widespread use of EMAs, some news outlets have started to use them as a channel to publish content specifically designed for EMAs in order to reach news audiences where they are.

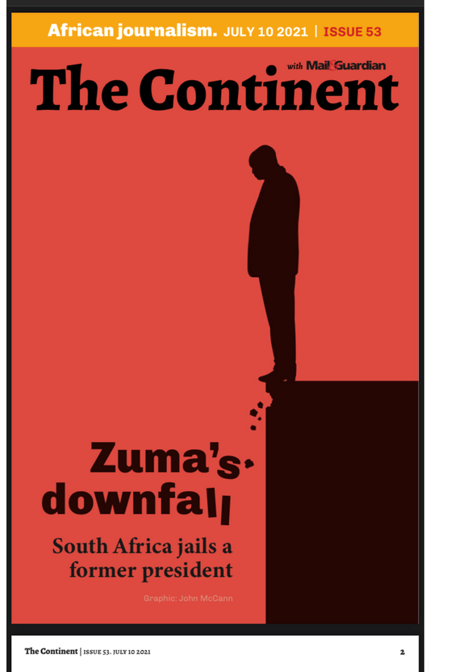

One recent example is The Continent, a weekly, pan-African PDF newspaper launched in April 2020 for Sub-Saharan Africa designed for reading and sharing primarily on WhatsApp.5 “Most of the people we know are getting their information from WhatsApp and yet there’s no major media house in our vicinity that is putting information there,” says Simon Allison, editor of The Continent, explaining the motivation behind developing a news product for WhatsApp.6

One recent example is The Continent, a weekly, pan-African PDF newspaper launched in April 2020 for Sub-Saharan Africa designed for reading and sharing primarily on WhatsApp.5 “Most of the people we know are getting their information from WhatsApp and yet there’s no major media house in our vicinity that is putting information there,” says Simon Allison, editor of The Continent, explaining the motivation behind developing a news product for WhatsApp.6

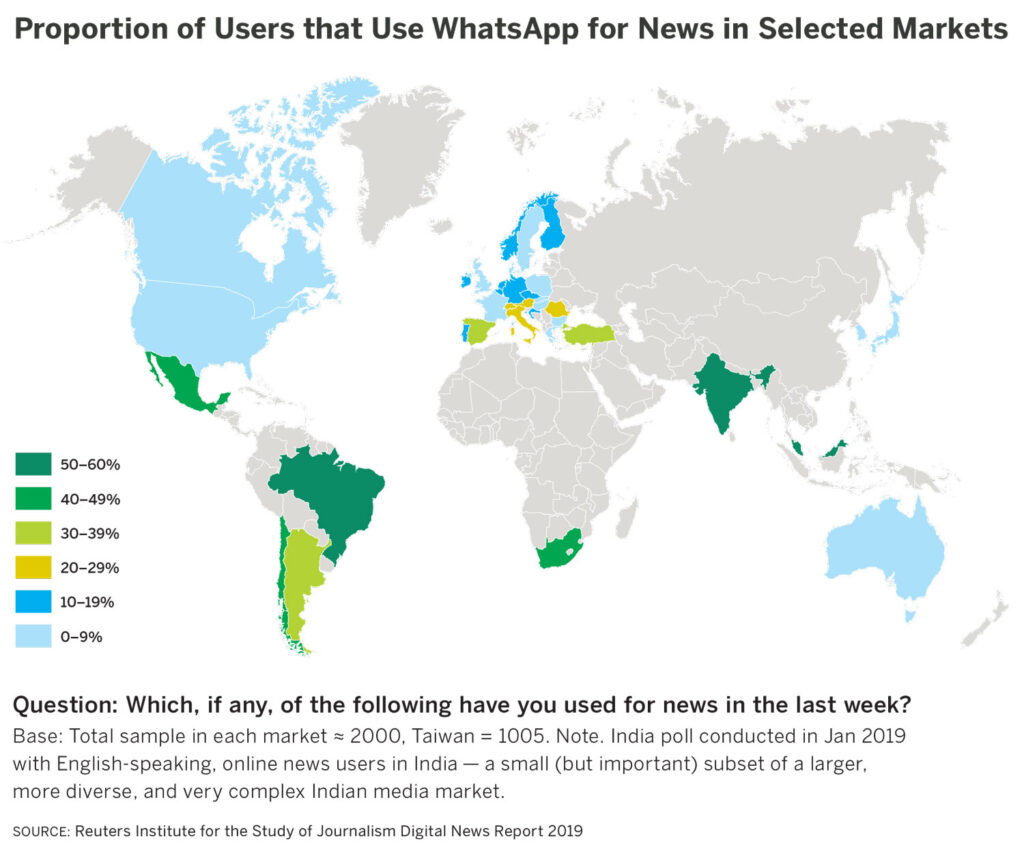

Disseminating news content through an EMA allows The Continent an opportunity to connect with audiences who may not consume news through print, TV, radio, and even news website and news apps. Research suggests audiences in South Africa, Nigeria, and Kenya, for example, rely more heavily on online sources, including social media and messaging apps, for news than TV or print.7 WhatsApp is cited as the most popular social media and messaging app for news in both Nigeria and Kenya and it is the second-most popular one in South Africa, where it falls slightly behind Facebook.8

Editors at The Continent want its product to correspond with how audiences already use WhatsApp. Its design is intended to encourage onward sharing to take advantage of its audience’s networks in order to extend its reach. To do this they limit the length of articles and the number of pages per edition as well as minimizing the PDF’s file size for quick sharing. This is not repurposing articles from another editorial product—a substantial amount of design, production, and journalistic resources are required to make each edition work for WhatsApp audiences.

Researchers and media analysts say that EMAs have contributed to the proliferation of digital disinformation because they allow for the spread of “untraceable claims to users via trusted contacts in a secure environment.”9 In some developing countries EMAs are seen as an even bigger part of the disinformation problem than traditional social network platforms.10 For its part, the team behind The Continent sees its use of EMAs as one way to distribute trustworthy, verified information. According to Sipho Kings, The Continent’s editorial director, the publication’s PDFs are designed to be easily digestible and shareable, with the goal of spreading high-quality independent reporting throughout the growing community of users who share news on encrypted messaging apps.11 By flooding WhatsApp with high-quality news, they hope to counter the spread of disinformation.12

The team at The Continent points to evidence that its content is being organically shared via readers’ networks. An audience survey conducted at the end of 2020 suggests that 1,300 respondents share an edition with at least six individuals via WhatsApp every week.13 Nonetheless, determining whether a news outlet’s EMA strategy is working in terms of countering the broader disinformation challenge remains difficult.

Although the ubiquity of EMAs on smartphones is often the initial draw for news outlets, that is not the only advantage of using these apps. Some news outlets have also found that EMAs allow more direct engagement with their audiences than social media. Jade Drummond, a digital strategist for the Brazilian technology news site Núcleo, argues that “using Telegram is different from social media because the information won’t be lost in people’s timelines.”14 The news outlet, which produces data-led investigations and analysis of the impact of technology on society, runs both a Telegram channel15 and a separate Telegram group.16 Núcleo started its Telegram channel shortly after its founding in 2020 because the platform is widely used by its target audience in the tech sector.17

A Telegram channel allows one-way broadcasting of updates—recipients can read updates and comment on them but not post messages to the channel. It can have an unlimited number of app users as subscribers. Núcleo updates the channel with breaking or trending news summaries, in text, images, and links to its investigative reports. It sees its Telegram channel as a more direct way to share its journalism with an audience, without depending on social media algorithms or competing with other trending topics on their timeline. This provides Núcleo a way to reach its audiences and keep them updated on what they are publishing, while also offering a platform for the audience to share feedback, comments, and doubts about stories.18

In contrast, a Telegram group allows both host and participants to post messages. Group administrators can restrict messages from members or set the group as private (invitation-only) or publicly accessible. Groups can have up to 200,000 members. In Núcleo’s Telegram group, Lixo Eletrônico (electronic garbage), the audience can share information, links, and thoughts. They are encouraged to participate by the outlet’s team, which responds and interacts with the group’s members. The group was specifically built to support one of Núcleo’s editorial newsletters that focuses on social media trends. Links and information shared by members to the Telegram group may feature in editions of the newsletter. The large group size and built-in privacy protection for the team and members—group members cannot see one another’s phone numbers—are advantageous features of the EMA for Núcleo: “The main goal is to bring our audience closer, make them part of our process, create a space for them to collaborate, feel heard, and grow our advocates. In that space, our team uses their own profiles to interact with the group, with a human approach instead of a brand talking to people.”19

For many news outlets around the world, the justification for creating bespoke EMA new products is simple—it’s where their audience is. The fact that EMAs have also been used to circulate disinformation is another reason that media outlets have sought to enter the space, helping audiences to access and share high quality news and information. As EMAs become a central feature of the digital information landscape, news outlets have sought to carve out a foothold on those platforms.

Circumventing News Censorship in Closed or Restricted News Media Environments

In some contexts, EMAs provide a mechanism for media outlets to publish and distribute news that is beyond state control and to provide coverage of news ignored by traditional media. Governments are starting to recognize the threat posed by news outlets using EMAs and have taken steps to restrict their use.

For example, in Zimbabwe, a country with a history of repressing the media, estimates for the number of WhatsApp users run as high as 5.2 million.20 By 2017, WhatsApp accounted for 44 percent of all mobile internet.21 News outlets there are using WhatsApp as one of their distribution channels to reach a wider audience and provide alternative coverage of social and policy issues that are not reflected in the country’s mainstream media.22

In 2017, following the coup d’état that forced the resignation of long-time dictator Robert Mugabe, rising demand for news prompted independent news outlet 263Chat23 to launch a daily PDF newspaper via WhatsApp. 263Chat started life as a Twitter account in 2012—hence its name, which combines Zimbabwe’s international dialing code and the idea of a discussion—and launched its website in 2014. Its WhatsApp PDF newspaper is designed to be easy to read on a phone and within the messaging app, with one article per page of 300-400 words. Founder Nigel Mugamu believes distributing news in this way offers a chance to increase civic engagement of people typically underserved by the country’s traditional media, such as those in rural or poor communities with limited access to reliable internet.24

WhatsApp has been blocked by the authorities in Zimbabwe on multiple occasions. In January 2019, for example, the government ordered internet service providers to shut off access to WhatsApp, Twitter, and Facebook for users.25 Access to the internet was also partially blocked. Human rights groups suggested this was an attempt to stop news of protests and violent government actions from being shared.26 As an online and social media news outlet, 263Chat, unable to distribute news during the shutdown, lost revenue.27 Running multiple WhatsApp groups to distribute its PDF newspaper, 263Chat increases its reach and has the contact details for a vast community of Zimbabweans at its fingertips. To protect this relationship with its audience and its place in the country’s media landscape as an alternative news source it must consider how to deal with future threats of censorship or internet shutdowns. To ensure that 263Chat can continue to publish its WhatsApp newspaper in such situations and circumvent the government’s attempts to censor the news, Mugamu will consider establishing a publishing partner or team member outside of Zimbabwe.28

The political context in which a news organization operates may encourage an outlet to use EMAs to distribute and publish news. It may also inform which EMA is selected and whether it is part of a long-term strategy, as with 263Chat, or a temporary workaround. Depending on how they operate, some EMAs can stay online during internet shutdowns because of their technological capabilities. Telegram, for example, stores all messages on a cloud-based secure server, which means devices using a virtual private network during an internet shutdown can still access the app—a feature currently not available on other apps. For news organizations operating in states with censorious regimes, Telegram may provide more reliable means of distributing news to audiences throughout periods of unrest or restricted access to social networks or news websites.

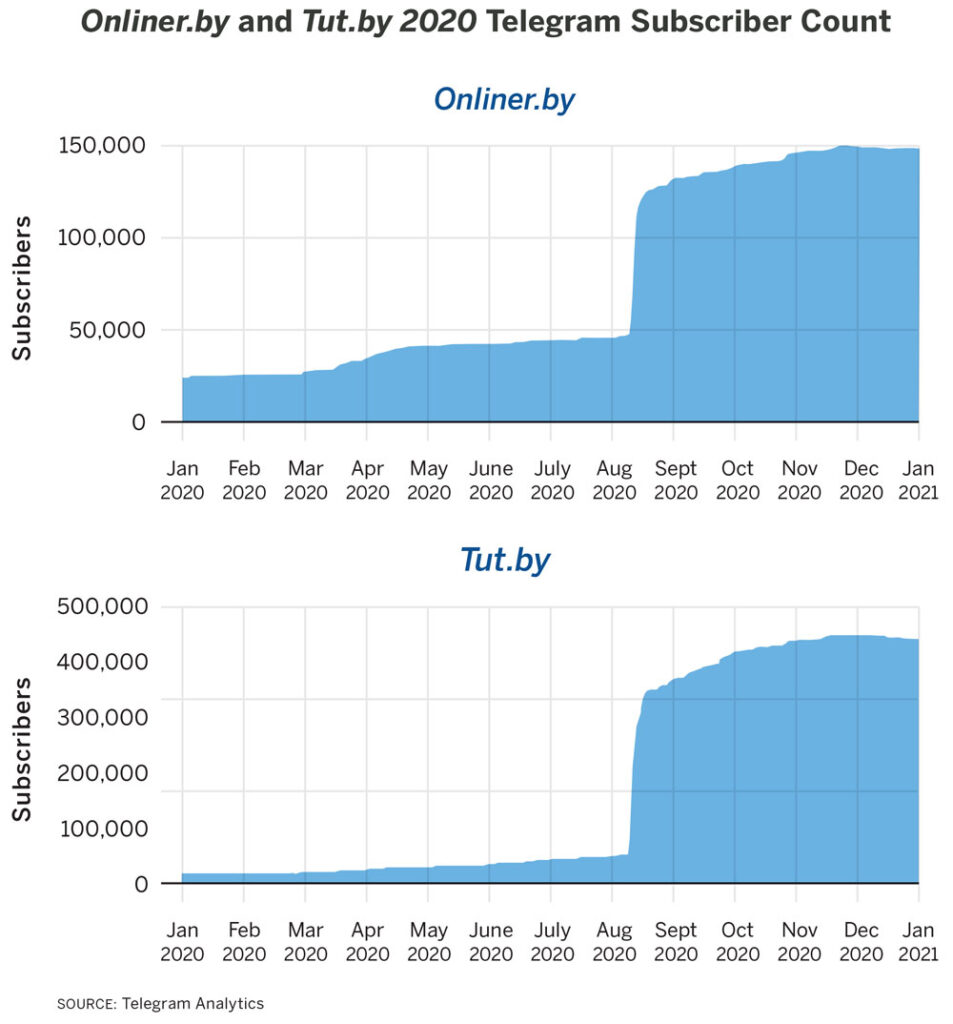

A clear example of Telegram’s utility in these contexts comes from Belarus, where it has been used by news outlets to circumvent censorship. On the morning of Belarus’ national elections in August 2020, state authorities allegedly shut down the country’s internet.29 Telegram was the only major digital communication platform still working in the country, prompting significant growth in the number of users in Belarus. The app’s linear feed in channels and groups lent itself well to live, rolling coverage of ongoing protests. Research from the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab,30 suggests that in the three months after the elections, subscribers to Telegram channels run by independent news organizations, such as Tut.by and Onliner.by,31 grew significantly. In July 2021, Tut.by’s website was blocked,32 but its Telegram channel of more than 582,000 subscribers was still active. Telegram enabled these news organizations to share story summaries, images and graphics; broadcast live updates on protests; and create a mechanism for audience members to share information for stories when other forms of communication were unavailable.

The lead researcher for the Baltics at DFR Lab, Nika Aleksejeva, suggests this growth resulted from Telegram’s reliable availability and the public’s desire for more comprehensive coverage of events that were unfolding in the country. “After more and more pro-Lukashenka [pro-government] Telegram channels appeared in response to reports about regime violence . . . People wanted more balanced and neutral news than conventional state-owned news outlets and Telegram channels run by [opposition] activists could provide.”33

For news organizations operating in restrictive political climates, EMAs may, therefore, offer a vital back-up in terms of distribution when other means of publishing, such as news websites or social media networks, are blocked by internet shutdowns or decreed illegal. EMAs are harder to block than websites, and Telegram’s cloud capability makes it better able to respond to broader internet shutdowns.

Citizen news and independent news outlets in Myanmar, such as Mogok Information Group34 and Frontier Myanmar,35 have used Telegram36 in the wake of internet shutdowns, internet access restrictions, and online surveillance enforced by the military junta under the leadership of commander-in-chief Min Aung Hlaing.37 Frontier Myanmar, which operates a news website, Facebook page, and Twitter account, launched its Telegram channel38 on June 23, 2021, posting summaries of its latest news stories with links to its website for those who could access it. Its last update to the channel, however, was just three weeks later on July 15, 2021, suggesting that Telegram has not replaced its main distribution channels despite its potential to operate in restrictive digital media environments. Frontier Myanmar stopped using Telegram after moving its operations to Thailand, where other channels with larger audience reach are available.

How news organizations might start and sustain an EMA channel launched in response to internet restrictions or digital media censorship is a question of resources and audience. Audiences may revert to websites, social media, and other news products as their main source of news if such restrictions are lifted—a challenge for news organizations looking at EMAs as part of a long-term strategy. Tut.by and Onliner.by, for example, gained hundreds of thousands of subscribers to their Telegram channels in the three months after the August 2020 elections39 as other online news sources became unavailable and public demand for independent coverage of events in Belarus surged. But after this surge, the size of the Telegram audience of Onliner.by steadily declined, other than a slight increase in May 2021.40 This uptick in interest likely corresponds with interest in independent coverage of the Belarusian government’s diversion of a Ryanair flight to arrest dissident Roman Protasevich, which created an international diplomatic row.41

Tut.by, on the other hand, was blocked by the government and its offices raided in May 2021, and the operation of its Telegram channel threatened.42 This suggests that while Telegram and other EMAs are useful as temporary back-ups to keep communication channels open during information blackouts or internet restrictions, they cannot always escape state intervention and may not have a long-term effect on how audiences prefer to access news.

In some countries, lawmakers are even debating legislation to restrict citizens’ access to EMAs or remove privacy features, such as encrypted messaging. Brazil’s National Congress has considered legislation that would force a “permanent identity stamp” to allow messages sent on the app to be traced to an individual user.43 A judge in Brazil previously ordered the app to be shut down for 48 hours.44 Similarly, home affairs ministers in the European Union in 2020 shared proposals for an end to encrypted messaging in situations where police agencies may wish to view or collect messages as evidence.45 Legislators in India have also challenged encryption on Signal and WhatsApp.46 Changing legal and political attitudes toward EMAs in a given region may make using those apps to publish news a non-starter for media outlets. If such laws are enacted, users may migrate away from affected apps, diminishing the audience opportunity for news organizations.

EMAs and Experiments with Monetization

Around the world, news organizations have also experimented with EMAs in order to create low-cost subscription-based business or distribution models. On the surface, all that is required is a phone, an EMA account, and a staff member to run it. However, converting these subscribers into paying consumers or making EMAs part of a sustainable business model is far from easy.

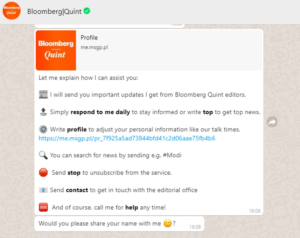

Business news site Bloomberg Quint (BQ),47 one of the first Indian publications to use EMAs for news publishing, launched its first WhatsApp service in 2017, sending business news summaries, links to stories on its website, and stock market updates to subscribers several times a day. This was an opportunity to meet its audience where they were: 60 percent of traffic to its website already came from mobile sources and 63 percent of respondents in an audience survey said they would prefer to receive news alerts by WhatsApp rather than email, SMS, or browser notifications.48 The majority of business news providers in India have broadcast licenses, but BQ does not. As such, growing a mix of alternative distribution channels, including EMAs, has allowed it to capitalize on the behaviors of its existing audience and compete in the market by reaching audiences through emerging digital platforms instead of broadcast media.49

BQ’s audience grew to around 400,000 subscribers in its first year of operation, dramatically increasing the volume of traffic on its website. Based on this, the news organization decided that this product should be its primary driver of organic audience growth for its website,50 where referrals could be monetized through subscriptions to content and paid access to articles.

Monetizing its WhatsApp audience more directly, however, has been a challenge for BQ. An experiment in which users visiting the BQ website via WhatsApp were served ads from a third-party commercial partner did not generate enough revenue to cover the cost of this arrangement.51 Efforts to build revenue from its WhatsApp service now focus on including articles available only to subscribers within the mix of updates that a BQ WhatsApp user receives, in the hopes of encouraging referred users to pay for access or for a website subscription.

Several news outlets in Latin America have also experimented with developing EMA-based revenue streams. For example, the Brazilian newspapers Estadão52 and Zero Hora53 have sponsors for news products created for WhatsApp distribution.54 Yet, research suggests that news media in this region are missing an opportunity to truly monetize EMA audiences.55 According to the data, just two of 18 outlets analyzed, Estadão and UOL Economia,56 feature ads or messages encouraging WhatsApp channel subscribers to sign up for paid products or membership programs.57 “[I]t doesn’t cost anything to ask for support for your member program, offer some subscription package, or even share advertisements there. Why not do it?” asks researcher Giuliander Carpes, who has examined EMA usage among Latin American news outlets.58

Newsrooms including BQ, The Continent, 263Chat, Núcleo, and local Brazilian newspaper Correio see potential in building more loyal audiences via EMAs—audiences that could help support the organization’s financial future. For example, BQ experimented with referral campaigns—getting subscribers to recruit friends and family to BQ’s channel—during its first use of WhatsApp. By the end of July 2018, its WhatsApp service had already acquired 186,210 new users through referrals from 23,974 existing users.59 This underscores the power of a core or loyal EMA audience to drive new audiences. It also indicates that learning how to grow and incentivize this loyal user base to sustain audience growth on EMAs should be a consideration for news organizations in this space.

Audiences have to opt-in to receive news via EMAs and, in the case of BQ, send a message and respond to questions about their news preferences. Vaibhav Khanna, BQ’s product manager responsible for growth, suggests this makes them more engaged from the get-go.60

Editors suggest that managing interactive groups on EMAs requires additional time and resources to be successful, potentially outweighing the benefits at this stage. Moderation tools in EMA groups are rudimentary. Group administrators, in this case, newsroom staff, can set which contacts are allowed to send messages to a group, block another group member’s contact number or delete messages, but these are individual, manual actions. Based on conversations with multiple news outlets, the time and resources needed to ensure that group chats stay on topic and are constructive are seen as better spent on building a broader distribution network and reaching different audiences.

Overall, the ability of news organizations to monetize their use of EMAs appears to be limited by the apps’ lack of commercial features that align with how newsrooms use them as well as with their editorial principles. A fee to access or subscribe to EMA channels is not an option for 263Chat, which is committed to keeping its news products available free of charge.61 Allowing businesses or commercial clients to directly access or post their messages in news organizations’ channels and groups for a fee was discounted as a viable revenue stream at this stage by all the news outlets interviewed for this report. Subscriber-only channels or EMA groups offering bespoke editorial content could offer new revenue streams but remain at the experimental or discussion stage.62 With PDF newspapers for EMAs, both 263Chat and The Continent have the option of carrying advertising in their editions. Both publications want to ensure that any advertising does not undermine their editorial independence and that advertising rates reflect the value of highly engaged EMA audiences. In August 2021, The Continent surveyed its EMA audiences on whether to accept an advertising proposal from a major bank to involve its audience in the direction of the newspaper and remain editorially and financially transparent. Just in the first week, the survey drew more than 400 responses, 82 percent of them in favor of accepting the advertising arrangement—but with the proviso that The Continent maintain its editorial independence.63

Overall, the ability of news organizations to monetize their use of EMAs appears to be limited by the apps’ lack of commercial features that align with how newsrooms use them as well as with their editorial principles. A fee to access or subscribe to EMA channels is not an option for 263Chat, which is committed to keeping its news products available free of charge.61 Allowing businesses or commercial clients to directly access or post their messages in news organizations’ channels and groups for a fee was discounted as a viable revenue stream at this stage by all the news outlets interviewed for this report. Subscriber-only channels or EMA groups offering bespoke editorial content could offer new revenue streams but remain at the experimental or discussion stage.62 With PDF newspapers for EMAs, both 263Chat and The Continent have the option of carrying advertising in their editions. Both publications want to ensure that any advertising does not undermine their editorial independence and that advertising rates reflect the value of highly engaged EMA audiences. In August 2021, The Continent surveyed its EMA audiences on whether to accept an advertising proposal from a major bank to involve its audience in the direction of the newspaper and remain editorially and financially transparent. Just in the first week, the survey drew more than 400 responses, 82 percent of them in favor of accepting the advertising arrangement—but with the proviso that The Continent maintain its editorial independence.63

“I think it’s a really important part of establishing editorial integrity, and establishing trust with readers,” editor Simon Allison said about the survey.64 “The Continent is in a place where we have been funded by donors that cover most of our core funding. Our readers know about this. We’re very clear about that. So bringing in advertising is a new thing and bringing in this particular form of advertising—an advertiser wanting us to do reporting on a specific issue—is a sort of gray area when it comes to how ethical that is, and so we thought it’s better to flag it before we do it.”

Experiments with revenue generation from EMA audiences are still at too early a stage to conclude how much and how consistently these audiences may contribute to a news outlet’s finances. Nonetheless, many news outlets are keen to experiment with EMA distribution to see if it can help generate new revenue.

Limitations of EMAs

Messaging apps were not built with the intention to serve news publishers and their audience growth goals—a challenge to the sustainability of any EMA publishing strategy. Many of their functions and policies hinder rather than help media outlets using them to distribute news. On EMAs, including Telegram, it is hard for news brands to stand out, as there is no difference in the appearance of a news channel from the individual and group chats, which, owing to their more personal connections among users, will compete for attention. WhatsApp, with its group and broadcast list size limits, manual operation, and mass messaging bans, for example, is intended to be a one-to-few rather than one-to-many communications channel.

While EMA channels and groups are initially easy to set up, publication and distribution via these channels are likely to involve manual, labor-intensive processes. Analytics for media outlets to better understand how their news updates travel to EMAs and who consumes them are limited. Viber, for example, offers some top-level demographic information65 on members of a “community” group (public group chats); while Telegram’s native analytics include channel subscribers, views, and details about languages of audience members with new options in development.66 Increasing commercial use of WhatsApp will help improve audience measure,67 though these additions are not aimed at news publishers’ analytical needs. Where this information is unavailable or too broad, news publishers struggle to assess the return on effort and investment or must run their own audience surveys on the channels to gather data.

While EMA channels and groups are initially easy to set up, publication and distribution via these channels are likely to involve manual, labor-intensive processes. Analytics for media outlets to better understand how their news updates travel to EMAs and who consumes them are limited. Viber, for example, offers some top-level demographic information65 on members of a “community” group (public group chats); while Telegram’s native analytics include channel subscribers, views, and details about languages of audience members with new options in development.66 Increasing commercial use of WhatsApp will help improve audience measure,67 though these additions are not aimed at news publishers’ analytical needs. Where this information is unavailable or too broad, news publishers struggle to assess the return on effort and investment or must run their own audience surveys on the channels to gather data.

“Our whole WhatsApp operation is just a person with a phone. That’s fine when you have 100 subscribers and you’re in the office,” explains Kate Wilkinson,68 deputy chief editor of the fact-checking organization Africa Check,69 which produces a podcast about viral misinformation on EMAs and social networks, distributed via WhatsApp voice notes and through its website.70 At the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, Africa Check’s WhatsApp phone was sent home with one staff member, who dealt with approximately 800 messages a day. “It’s a cheap, simple, effective way to distribute accurate information to people who want it, but if you become too successful, it will become unmanageable,” says Wilkinson.

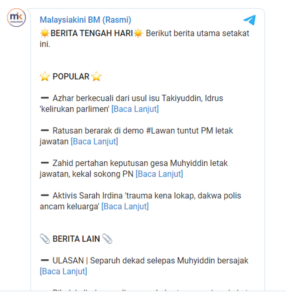

Platforms may change features or policies at any time and news publishers must weigh benefits against the cost of continual adaptation. News media were hit hard by WhatsApp’s rules banning automated or bulk messaging,71 for example. For news outlets such as MalaysiaKini,72 it is tempting to skirt these rules on WhatsApp because of the app’s audience size. Yet, the risk of breaching WhatsApp’s terms and incurring punitive measures is too great.73 It uses multilingual Telegram channels instead, where mass messaging does not risk punitive measures from the platform but also doesn’t have the same scale or rate of growth as WhatsApp in Malaysia.74

“WhatsApp is a golden market for us, but we don’t know to what extent it would punish us [for violating mass messaging rules]. If there are changes to the rules for publishers, that will be huge,” says Zikri Kamarulzaman, a MalaysiaKini journalist.75

BQ knows the limitations of EMAs all too well. Its first WhatsApp broadcast channels amassed more than 500,000 subscribers, using a series of phone numbers to circumvent the app’s restrictions to publish briefings, news summaries, and international markets news.76 In December 2019, WhatsApp announced it would take legal action against people using the EMA for bulk or automated messaging.77 BQ’s use of the app at that time would fall foul of this new policy. As such, it had to “let go”78 of its substantial WhatsApp audience79 and start again with WhatsApp Business. EMAs are commercial entities, often with billionaire owners or big tech backers,80 accountable to their investors, not their users or news outlets adapting their technology.

The future of some EMAs may be decided by the principles and personal mission of their founders. Telegram’s founder, for example, says the app’s privacy is non-negotiable and will continue to resist security services’ efforts to obtain access to the platform and its messages.81 Zakhar Protsiuk, co-founder and an editor of European media news site The Fix, believes Telegram’s built-in protections against censorship are likely to survive in the long term. But he says this could be challenged if the platform ever decides to compromise on its stance on privacy to “become a dominant messaging platform in the West” or if governments learn how to block the platform.82 Decisions made by app owners, both personally and business-motivated, will inform the future direction and features of EMAs, including their utility for news organizations. This uncertainty should be taken into consideration by news outlets contemplating an EMA strategy.

Conclusion

The sheer volume of people using EMAs in certain markets is enticing to news publishers looking to expand their audiences. News organizations’ experiments so far have explored how aspects of EMAs’ design could benefit their audience reach and growth, distribution model and, in cases such as The Continent and 263Chat, inform new editorial products. The more closed nature of communication on EMAs and the technology underpinning some of these apps has enabled news publishing to continue in some restricted media environments, suggesting EMAs could play a role in preserving media freedom in the face of efforts to muzzle the press. Pilot tests are also being conducted on whether audiences subscribing to news outlets’ EMA channels and groups are more likely to financially support them, either through direct donations, paid subscriptions, deeper engagement with websites carrying ads, or commercial activities in the channels and groups themselves.

Yet the potential of EMAs for news organizations is undermined by the fact that these apps are not designed for news publishers and have features that limit what news outlets are able to do with them. Managing subscribers, creating and sending messages, and moderating group chats are all largely manual processes required to grow and sustain audiences on EMAs. The more bespoke an editorial product for EMAs, the more resources that are required for its design and execution. It would likely cost significant human and financial resources for a news outlet to make an EMA strategy work. Clear evidence of the business case for EMAs and how these apps could be monetized for news outlets is lacking.

When working with media in markets where EMAs are widely used or have the potential to reach specific audiences, international donors and media outlets should keep these experiments in mind. The examples of media outlets using EMAs in South Africa, Zimbabwe, India, and Belarus show that it is critical for newsrooms and media support organizations to assess audience demands and their own internal resources before embarking on an EMA strategy.

A substantial risk to the sustainability of news publishing and distribution via EMAs lies in the uncertainty of the platforms themselves. Feature changes and policy updates have thrown many news outlets’ efforts in this space off course or shut down channels after years of audience growth. This unpredictability is compounded in countries where governments are trying to block EMAs or regulate their use by citizens. News publishers must decide if the audience opportunity presented by EMAs is sufficiently large or likely to provide enough revenue to justify the resources required to publish and distribute via these apps at scale and withstand the pressure from external forces that will inform—and maybe threaten—their long-term future.

Footnotes

- Statista, “Most popular global mobile messaging apps 2021,” August 2, 2021, https://www.statista.com/statistics/258749/most-popular-global-mobile-messenger-apps/.

- Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Antonis Kalogeropoulos, Rasmus Klein Nielsen, Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2019 (Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, June 12, 2019), https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/inline-files/DNR_2019_FINAL.pdf.

- Daniel O’Maley and Amba Kak, Free Internet and the Costs to Media Pluralism: The Hazards of Zero-Rating the News (Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance, November 8, 2018, https://www.cima.ned.org/publication/zero-rating-the-news/.

- Manish Singh, “WhatsApp introduces new limit on message forwards to fight spread of misinformation,” TechCrunch, April 7, 2020, https://techcrunch.com/2020/04/07/whatsapp-rolls-out-new-limit-on-message-forwards.

- It is also available via Signal and back issues of PDF editions can be downloaded from its website. The Continent, https://mg.co.za/continent-archives/.

- Laura Oliver, “How publishers are engaging new audiences on messaging apps in the Global South,” Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, March 2, 2021, https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/risj-review/how-publishers-are-engaging-new-audiences-messaging-apps-global-south.

- Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, Craig T. Robertson and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen, Reuters Digital News Report 10th Edition (Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, June 23, 2021), https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/digital-news-report/2021.

- Ibid.

- Jacob Gursky and Samuel Woolley, Countering disinformation and protecting democratic communication on encrypted messaging applications (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, June 2021), https://www.brookings.edu/research/countering-disinformation-and-protecting-democratic-communication-on-encrypted-messaging-applications/.

- Ibid.

- Sipho Kings, “Safeguarding New Social Media Platforms: A WhatsApp Newspaper that Meets Readers Where They Are,” in Innovation in Counter-Disinformation: Toward Globally Networked Civil Society, eds. Kevin Sheives and John Engelken (Washington, DC: International Forum for Democratic Studies, 2021), https://www.ned.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Global-Insights-Innovation-in-Counter-Disinformation-Toward-Globally-Networked-Civil-Society.pdf, 9-15.

- Isaac Kwaku Fokuo Jr, “Simon Allison on the Future of African Media,“ Afro-Catalyst, February 26, 2021, https://www.listennotes.com/podcasts/afro-catalyst/simon-allison-on-the-future-Zr5gP2nz-i9/.

- Laura Oliver, “How publishers are engaging new audiences on messaging apps in the Global South.”

- Personal communication, Jade Drummond, June 16, 2021.

- “Núcleo Jornalismo,” Telegram, https://t.me/nucleojor.

- “Lixo Eletrônico,” Telegram, https://t.me/joinchat/YfgEgDLRjDQyOTZh.

- Personal communication, Jade Drummond, June 16, 2021.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Sharon Mazingaizo, “How Zimbabwe’s ‘WhatsApp classrooms’ are helping pupils learn during the pandemic,” Times Live, June 30, 2021, https://www.timeslive.co.za/news/africa/2021-06-30-how-zimbabwes-whatsapp-classrooms-are-helping-pupils-learn-during-the-pandemic.

- Tawanda Karombo and Commentary, ”Nearly half of all internet traffic in Zimbabwe goes to WhatsApp,” Quartz, October 28, 2017, https://qz.com/africa/1114551/in-zimbabwe-whatsapp-takes-nearly-half-of-all-internet-traffic/.

- Julia Thomas, “WhatsApp has come in to fill the void: In Zimbabwe, the future of news is messaging,” NiemanLab, March 13, 2019, https://www.niemanlab.org/2019/03/whatsapp-has-come-in-to-fill-the-void-in-zimbabwe-the-future-of-news-is-messaging/.

- 263Chat, https://www.263chat.com.

- Laura Oliver, “How publishers are engaging new audiences on messaging apps in the Global South.”

- BBC, ”Zimbabwe blocks Facebook, WhatsApp and Twitter amid crackdown,” January 18, 2019, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-46917259.

- Ibid.

- Zimbabwe Independent, “Internet shutdown disastrous for brand Zim,” January 25, 2019, https://www.theindependent.co.zw/2019/01/25/internet-shutdown-disastrous-for-brand-zim/.

- Laura Oliver, “How publishers are engaging new audiences on messaging apps in the Global South.”

- Andrei Makhovsky and Tom Balmforth, “Internet blackout in Belarus leaves protesters in the dark,” Reuters, August 11, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-belarus-election-internet-idUSKCN2571Q4.

- Nika Aleksejeva, “Belarusian activist Telegram channels are losing their audience,” Digital Forensic Research Lab, November 18, 2020, https://medium.com/dfrlab/belarusian-activist-telegram-channels-are-losing-their-audience-e4afb34f19bc.

- Onliner.by, https://www.onliner.by/.

- “Belarus authorities block the most popular news site in the country,” The Fix, May 20, 2021, https://thefix.media/2021/05/20/belarus-authorities-block-the-most-popular-news-site-in-the-country/.

- Personal communication, Nika Aleksejeva, June 21, 2021.

- Facebook group, Mogok Information Group, https://www.facebook.com/groups/2538382249750845.

- Frontier Myanmar, https://www.frontiermyanmar.net/en/.

- “Journalism goes local as the junta shackles national media,” Frontier Myanmar, May 28, 2021, https://www.frontiermyanmar.net/en/journalism-goes-local-as-the-junta-shackles-national-media/.

- “Junta steps up phone, internet surveillance – with help from MPT and Mytel,” Frontier Myanmar, July 5, 2021, https://www.frontiermyanmar.net/en/junta-steps-up-phone-internet-surveillance-with-help-from-mpt-and-mytel/.

- “Frontier Myanmar,” Telegram, https://t.me/frontiermyanmar.

- Nika Aleksejeva, “Belarusian activist Telegram channels are losing their audience.”

- Telegram Analytics, https://by.tgstat.com/en/channel/@onlinerby.

- “Belarus diverts Ryanair flight to arrest journalist, opposition says,” BBC News, May 23, 2021, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-57219860.

- Ilya Yablokov, “Belarus’ most famous media outlet wants its title back – and its people freed,” October 16, 2021, OpenDemocracy, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/odr/tut-belarus-media-zerkalo-interview/.

- WhatsApp, “The threat of traceability in Brazil and how it erodes privacy,” https://faq.whatsapp.com/general/security-and-privacy/the-threat-of-traceability-in-brazil-and-how-it-erodes-privacy.

- Julie Ruvolo, ”UPDATE: Brazilian Judge Shuts Down WhatsApp And Brazil’s Congress Wants To Shut Down The Social Web Next,” TechCrunch, December 17, 2015, https://techcrunch.com/2015/12/16/brazils-congress-has-shut-down-whatsapp-tonight-and-the-rest-of-the-social-web-could-be-next/.

- Jordan Butt, ”Europe looks to crack open data encryption on messaging services like WhatsApp,” CNBC, November 23, 2021, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/11/23/europe-looks-to-crack-open-data-encryption-on-messaging-services.html.

- Deeksha Bhardwaj, ”Messaging app Signal not in compliance with new rules, say officials,” Hindustan Times, June 24, 2021, https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/messaging-application-signal-not-in-compliance-with-new-rules-say-officials-101624508925464.html.

- Bloomberg Quint, https://www.bloombergquint.com/.

- Abhishek and Saral Mukherjee, “BloombergQuint: Growing Users with WhatsApp,” Institute of Management Technology Ghaziabad, Harvard Business Review, March 19, 2019, https://store.hbr.org/product/bloombergquint-growing-users-with-whatsapp/A00224.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Estadão, https://www.estadao.com.br/.

- GZH, https://gauchazh.clicrbs.com.br/.

- Marina Estarque, ”Most Brazilian media use WhatsApp in a limited way and miss opportunities to generate revenue from the app, says researcher,” LatAm Journalism Review, August 18, 2021, https://latamjournalismreview.org/articles/most-brazilian-media-use-whatsapp-in-a-limited-way-and-miss-opportunities-to-generate-revenue-from-the-app-says-researcher/.

- Ibid.

- UOL Economia, https://economia.uol.com.br/.

- Giuliander Carpes and Enric Moreu, ”WhatsAppening to the News: How news organizations are using WhatsApp to distribute news and engage audiences in Brazil,” April 25, 2021, https://whatsappening.joltetn.eu/.

- Marina Estarque, ”Most Brazilian media use WhatsApp in a limited way and miss opportunities to generate revenue from the app, says researcher.”

- Abhishek and Mukherjee, “BloombergQuint: Growing Users with WhatsApp.”

- Personal communication, Vaibhav Khanna, May 19, 2021.

- Laura Oliver, “How publishers are engaging new audiences on messaging apps in the Global South.”

- Ibid.

- Hanaa‘ Tameez, “Here’s why The Continent asked its readers if it should accept an advertising deal,” NiemanLab, October 12, 2021. https://www.niemanlab.org/2021/10/heres-why-the-continent-asked-its-readers-if-it-should-accept-an-advertising-deal/.

- Ibid.

- Michael Bauernfreund, “Community Insights: Measure The Success of Your Community,” Viber blog, March 12, 2019, https://www.viber.com/en/blog/2019-03-12/measure-the-success-of-your-community/.

- Telegram Analytics Project Channel, https://t.me/s/tg_analytics_en.

- Facebook for Developers, https://developers.facebook.com/docs/whatsapp/business-management-api/analytics/.

- Personal communication, Kate Wilkinson, July 5, 2021.

- Africa Check, https://africacheck.org/.

- Africa Check, ”What’s Crap on WhatsApp,” https://www.whatscrap.africa/.

- WhatsApp, “Stopping Abuse: How WhatsApp Fights Bulk Messaging and Automated Behavior,” February 6, 2019, https://chatbot.com.hr/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/WA_StoppingAbuse_Whitepaper_020418_Update.pdf.

- MalaysiaKini, https://www.malaysiakini.com/

- Personal communication, Zikri Kamarulzaman, May 21, 2021.

- Joschka Müller, “Share of internet users using communication applications in Malaysia as of May 2020, by app,” Statista, April 7, 2020, https://www.statista.com/statistics/973428/malaysia-internet-users-using-communication-apps/.

- Personal communication, Zikri Kamarulzaman, May 21, 2021.

- Personal communication, Vaibhav Khanna, May 19, 2021.

- WhatsApp, “Security and Privacy,” https://faq.whatsapp.com/general/security-and-privacy/unauthorized-use-of-automated-or-bulk-messaging-on-whatsapp.

- Personal communication, Vaibhav Khanna, May 19, 2021.

- BloombergQuint, “How To Sign Up For BloombergQuint Story Notifications,” December 6, 2019, https://www.bloombergquint.com/business/how-to-sign-up-for-bloombergquint-story-notifications.

- Abram Brown, “Meet The Billionaires Behind Signal And Telegram, Two New Online Homes For Angry Conservatives,” Forbes, January 13, 2021, https://www.forbes.com/sites/abrambrown/2021/01/13/meet-the-billionaires-behind-signal-and-telegram-two-potential-new-online-homes-for-angry-conservatives.

- “Privacy is not for sale, promises Telegram founder Pavel Durov adding the app will use built in systems to bypass Russian ban,” First Post, April 14, 2018, https://www.firstpost.com/tech/news-analysis/privacy-is-not-for-sale-promises-telegram-founder-pavel-durov-adding-the-app-will-use-built-in-systems-to-bypass-russian-ban-4431285.html.

- Personal communication, Zakhar Protsiuk, July 9, 2021.