Key Findings

For years, democracy around the world has been in retreat. Dictators have made every effort to reassert their hold on power, with independent media often a first line of attack. Despite this troubling trend, movements for democracy are constantly emerging, ushering in new windows of opportunity for democratic progress. Reforming the media sector is central to ensuring the success of a democratization effort. Yet, the path to progress is not straightforward—reform efforts can easily stall, and media advocates face strong headwinds as they contend with entrenched political and business interests vying for control of the information space.

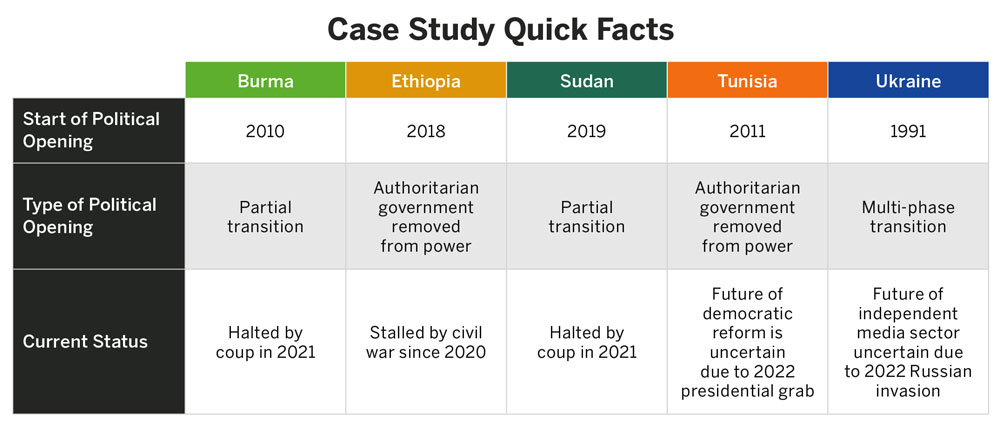

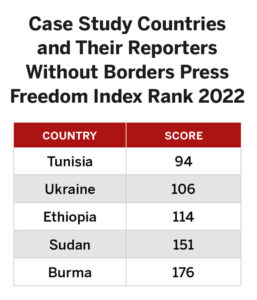

By examining past and current political openings—Burma, Ethiopia, Sudan, Tunisia, and Ukraine—this report explores how media sector advocates advance a progressive reform vision during democratic transitions and how the international community can best support them. The case studies demonstrate the importance of contextually tailored support for media, and highlight the key role of civil society as a driving force for a media reform agenda.

– There is no one-size-fits-all blueprint for supporting media in times of political opening. Local ownership of a media reform vision and cross-sectoral collaboration are key, and priorities need to be set based on the needs and capacities of local reform groups.

– Given the oft-volatile and frequently short-lived nature of these openings, early gains are critical to the success of a media reform movement and can have long-lasting effects, even in the face of authoritarian retrenchment.

– Authoritarian legacies leave a lasting mark on institutions and political instability can lead to long periods of stagnation or regression. International support that is long-term and driven by a deep understanding of the threats to a free and independent media, as well as levers of progress, is critical to helping reformers advance their aims.

Introduction

Dictators fall. Civil conflicts end. Elections bring opposition groups to power. Historical junctures such as these provide rare windows of opportunity for democratic reform as transitional governments and reformers pave the way from the old autocratic regimes toward new, more democratic forms of government. Change of such magnitude requires societies to embark on the monumental task of building more inclusive and accountable institutions—a task that has no clear path, destination, or timeline.

Establishing a vibrant and independent media system is often a priority in these openings. Are the media able to take on a role that supports a viable democratic political process? Or do they impede the consolidation of the emerging democracy?1 An open and plural news media environment is essential for promoting good governance and rule of law, creating conditions for fair elections, and fostering citizen participation in policy deliberations.2 The democratic reform process itself often depends on the successful development of the media sector.

In countries experiencing a political opening or struggling with the challenges of democratization, establishing robust legal frameworks and media institutions is indispensable to successful media sector reform. Formal protections for freedom of expression, media freedom and independence, and access to information are essential in preventing authoritarian or post-authoritarian regimes from stifling the rights that form the basis for an independent, professional, and plural media sector.

However, the legacies of previous authoritarian regimes can be persistent. Reformers must struggle with entrenched political and business interests vying to retain a grip on the media. This has been especially true amid the current global democratic recession.3 Since 2006, the countries experiencing democratic backsliding have outnumbered those making progress. Political openings are frequently short-lived, and often followed by a reassertion of an authoritarian regime’s authority, albeit with weakened legitimacy. In some cases, the opening results in a robust democratization push, but even in these cases the process is long and fraught with political uncertainty and upheaval.

How far the media sector reforms can go will depend on how substantially power has been redistributed from the old authoritarian elite to a new set of emerging pro-democracy actors. Numerous factors and forces help determine whether a vibrant, plural, and truly independent media sector can emerge in the wake of political upheaval. Top among these are the strength of institutions and regulatory frameworks to govern the sector, the political will and capacity of reformist governments, the ability of civil society to develop a reform vision and articulate public demand, and the influence of outside actors.

International support for independent media and civil society has contributed meaningfully in the past to the success of reform efforts in countries experiencing a political opening.4 But in a time of political upheaval, old blueprints for international cooperation and support are coming under renewed scrutiny—international donors providing funding for reform efforts have at times misjudged a political moment and underestimated the persistent influence of anti‑democratic elements.

International support for independent media and civil society has contributed meaningfully in the past to the success of reform efforts in countries experiencing a political opening.4 But in a time of political upheaval, old blueprints for international cooperation and support are coming under renewed scrutiny—international donors providing funding for reform efforts have at times misjudged a political moment and underestimated the persistent influence of anti‑democratic elements.

How are media sector reformers adapting their strategies in the challenging political climates they face, and how can the international community best support them? Five cases of unstable political openings—Burma, Ethiopia, Sudan, Tunisia, and Ukraine—are examined in this report to help shed light on these questions. More than 140 interviews were conducted in 2021 with experts, civil society advocates, government reform champions, and international and multilateral donors and implementers working in these five countries. Drawing lessons across these diverse contexts and historical trajectories provides numerous lessons that can be instructive for local advocates and reformers, international donors, and media development implementing organizations.

While formal institution building and consolidation are critical processes in the transformation of media systems during transition, these efforts alone are often not sufficient to maintain the momentum needed for long-term, sustainable reform. In many cases, an overarching focus on formal, technocratic institution building has caused reform efforts to stall. Transitional governments may pay lip service by supporting the establishment of formal institutions that are undermined in practice. This is not surprising since in many cases, the new government has entrenched interests that are linked to the previous regime, and often has the most to lose from such reforms.

For this reason, the importance of informal institutions—i.e., the norms, values, practices, and processes of building political will, consensus, and commitment—and the grassroots efforts to foster and maintain momentum for reform must not be underestimated.5 Building sustainable media institutions requires an enabling environment supported by grassroots efforts that are non-state, and often non‑commercial. Such efforts are typically led by civil society and include broad, multistakeholder reform coalitions and movements, membership organizations, and voluntary self-regulatory bodies such as press unions and professional societies.

Along with a vibrant civil society, international assistance, such as funding and technical support, is often critical to building a truly independent media sector bolstered by strong institutional and legal frameworks.6 Such support, often in the form of foreign aid and technical expertise, can help strengthen the efforts of civil society, marshal the political will necessary to promote institutional and policy reforms, and expand the number and diversity of news outlets that are operating independently and in the public interest.

Along with a vibrant civil society, international assistance, such as funding and technical support, is often critical to building a truly independent media sector bolstered by strong institutional and legal frameworks.6 Such support, often in the form of foreign aid and technical expertise, can help strengthen the efforts of civil society, marshal the political will necessary to promote institutional and policy reforms, and expand the number and diversity of news outlets that are operating independently and in the public interest.

Examples from different contexts show that many attempts at media reform are not sufficiently attuned to the challenges and opportunities on the ground. Media reform proposals and projects are often supply-driven and exclude local actors from analysis of the problems and development of solutions. Moreover, international assistance typically relies on government as the main driver of reforms, but in fragile and post-authoritarian contexts, government engagement is often nothing more than window dressing, performed to score diplomatic points. Once the donors pull out, introduced reforms can be scaled back or completely abandoned as entrenched interests reassert themselves. What is frequently missing in such circumstances is broad-based popular demand for democratic reforms, articulated via reform-minded coalitions or movements. In other words, the supply of democratic media institutions and practices must correspond to the demand for democracy among the broader population, civil society groups, and activists.

Given all of the above, this research explores the nexus between international assistance, civil society, and local political actors and institutions, and how these forces interact and shape media democratization efforts. The study scrutinizes the interaction between international media assistance approaches on one side, and local demand for media reforms, galvanized through civil society initiatives, coalitions, and movements, on the other, within the broader political context of countries attempting to depart from authoritarian regimes toward more democratic forms of governance.

The five countries that are the focus of this report all have in common an authoritarian legacy and faltering attempts at democratic transition. However, they differ significantly in terms of the nature, trajectory, and outcomes of their transitional efforts so far, affecting their media reforms as well. Burma and Sudan, for instance, emerged from decades of military rule, and experienced only a partial opening under the dominant role of the military, with a much weaker civilian component of the government. Burma’s transition to democracy started in 2010, but the country only had its first democratic elections in 2015. Protests in Sudan led to toppling the 30-year dictatorship of President Omar Al-Bashir in April 2019. Both countries ended their democratization experiments with a military coup d’état in 2021.

The five countries that are the focus of this report all have in common an authoritarian legacy and faltering attempts at democratic transition. However, they differ significantly in terms of the nature, trajectory, and outcomes of their transitional efforts so far, affecting their media reforms as well. Burma and Sudan, for instance, emerged from decades of military rule, and experienced only a partial opening under the dominant role of the military, with a much weaker civilian component of the government. Burma’s transition to democracy started in 2010, but the country only had its first democratic elections in 2015. Protests in Sudan led to toppling the 30-year dictatorship of President Omar Al-Bashir in April 2019. Both countries ended their democratization experiments with a military coup d’état in 2021.

In Ethiopia, popular pressure did not overthrow the regime but forced the incumbent party to appoint new leadership in 2018 with a broad mandate to undertake political and economic reforms. Attempts to reassert strong, central state institutions faced resistance from forces who favor a decentralized, ethnic federalist system,7 contributing to tensions that culminated in outbreaks of violence in Tigray in 2020,8 halting most of the reforms.

In Tunisia, the transition was triggered by a popular unrest in 2011 that ended the two-decade-long reign of President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, resulting in substantial redistribution of power. Despite initial progress, Tunisia has experienced a protracted stagnation and the fragile political system is in a state of paralysis, unable to address fundamental issues such as economic or security sector reform. In July 2021, due to the prolonged political gridlock, President Kais Saied “seized governing powers, dismissed the prime minister and suspended parliament”9 and subsequently started to rule by decree while preparing the changes to the political system.10 The outcome of Tunisia’s transition is now highly uncertain.

Finally, Ukraine gained independence and started a protracted and turbulent democratization path after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. It has now entered its fourth decade of transformation, oscillating between phases of democratic reform and phases of stagnation and authoritarian rollback. As the country announced a move away from Russian influence and reorientation toward potential European Union (EU) membership after the 2014 Revolution of Dignity, Russia intervened militarily to exert pressure on Ukraine. It annexed the Crimean Peninsula in 2014 and occupied part of the eastern Donbas region. Since February 2022, a new phase of full-scale Russian invasion has been unfolding, aimed at returning Ukraine under its influence and pulling it away from potential EU and North Atlantic Treaty Organization membership.

By analyzing the selected countries, key lessons emerge about how momentum for reforms can be catalyzed and maintained by supporting grassroots, demand-driven initiatives even in the most volatile countries. The approach also provides an opportunity to investigate legacies, best practices, and lessons learned for those cases where democratization has been suddenly interrupted, as in Burma and Sudan, or radically disrupted, as in Ethiopia, Tunisia, and Ukraine.

This report provides a synthesis of findings that are elaborated in more detail in individual country reports (see: Burma, Ethiopia, Sudan, Tunisia, and Ukraine).

An Overview of Media Reforms in the Five Case Study Countries

In all five countries covered by this research, efforts have been undertaken to reform formal institutions relevant for the media sector and foster press freedom. The ambition and effects of attempted reforms vary greatly among the five countries, reflecting the openness of the regime for change and leverage of the actors demanding more democratic media systems.

In some cases, the reforms took place during nascent political openings in recent years that have since been partly or entirely reversed; in others, political transitions have been underway for longer and have taken different trajectories.

In Burma, the trends within the media sector closely reflected the political processes in the country. Following the 2010 political opening, only a few weekly and monthly journals and magazines were independent, while the military and its allies controlled broadcasting. In early 2012, Burma’s government announced an ambitious media reform agenda. Pre-publication censorship was abolished, and a news media law introduced some limited journalistic rights. Some exiled media returned to the country, and imprisoned journalists were freed. As part of a reform package, a press council was established as a de facto quasi-governmental body. However, it was sidelined by both the civilian part of the government and the military, while the use of criminal laws against journalists persisted. In effect, core mechanisms of self-regulation and professionalization of journalism never truly became operational. Similarly, a broadcast law was adopted in 2015 allowing the operation of new private broadcasters, public service media, and community media, and stipulating core principles of freedom of expression and media pluralism. But the law never became effective, as key bylaws and regulations were not adopted. The broadcast sector remained under stringent government and military control. By 2014, the crackdown on independent voices started again, escalating in 2016. The law on the right to information was drafted in 2017 with the participation of a broad civil society coalition. Nevertheless, a watered-down version without some key provisions was submitted to the Ministry of Information, which took no further action. In short, the reform attempts had largely failed by the end of the decade of political opening. Since the military coup in February 2021, it has no longer been possible to do independent journalism in the country.11

In Ethiopia, beginning in 2018 as a response to a series of mass protests against the ruling party, the government outlined an aspiring agenda for media reforms. Thousands of political prisoners, including journalists, were freed, and charges were dropped against opposition media. More than 260 blocked websites were allowed to operate freely. Twenty-three broadcasters and 13 print media outlets have filed for registration since the start of the transition.12 Consequently, Ethiopia made significant progress in Reporters Without Borders’ 2019 World Press Freedom Index, moving up from 150th out of 180 countries to 110th.13 The reform agenda resulted from broad consultations involving leadership from civil society. Important progress was made initially, including a review of several repressive laws and the adoption of a new media law14 in February 2021. The new media law decriminalized defamation, loosened strict media registration and licensing criteria, introduced ownership provisions to restrict political control over the media, and created a legal basis for self-regulation. The law also provides guarantees for the independence of a media regulatory organ and public media institutions by making them accountable to parliament instead of the executive. In addition, a Freedom of Information Proclamation was drafted, stipulating substantial changes that would bring the regulatory framework for access to information in line with best international practices. The provisions of the draft law include mechanisms of administrative accountability, penalties for non-compliance, and the creation of an information commission.

Despite this progress, numerous challenges remain. One significant obstacle is a culture of strong government control over the media, which are deeply embedded in state institutions. Abuses of journalists continue due to harassment from security forces and use of repressive laws that have yet to be repealed.15 In the broadcast sector, the ruling party still controls the most important radio and television stations16 and political competitors control the rest, with little room left for independent media. The scale of media capture by the state, political parties, and business interests substantially undermines the viability of reform efforts.17 Additionally, misinformation and hate speech pose a significant problem to an ethnically polarized public sphere, and these issues are especially prominent on social media. More importantly, since late 2020 the country has been embroiled in civil war, which has halted any substantial progress on media reforms.18

In the case of Sudan, the government did not embark on an ambitious reform agenda, and the little progress achieved was frustrated by a deadlock between the military and civilian components of the government from the very beginning. However, after the political opening, news media were allowed more freedoms than before. The interim constitution of August 2019 guarantees the right to freedom of expression, freedom to access information and publications, freedom of the press and other media, and the right to access the internet.19 In effect, systematic censorship on some issues, such as coverage of the government and international relations, ended. In addition, systemic repressive actions by the security apparatus stopped, as the National Intelligence and Security Services was dissolved the same year. Arbitrary arrests of journalists were rare, while harassment of online activists decreased significantly.20 Licenses were granted to some new media outlets, but the private media sector remains relatively small by African standards.21

Overall, the Sudanese government was very slow to enact more substantial reforms for the media sector, or to embrace initiatives from civil society and international donors. Although the government established a media reform committee immediately after the political opening that included civil society organizations (CSOs), it achieved no progress. Consequently, the status of the Roadmap for Media Reform in Sudan of 2019,22 sponsored by UNESCO, remained uncertain due to the government’s inaction. While most of the laws that stifled press freedom were revoked in 2020 and early to mid-2021, no new laws have been adopted. Moreover, the National Press and Publications Council, a repressive institutional legacy of the old regime, remains operational, wielding a range of powers such as granting of licenses for newspapers and imposing fines on publishing houses. However, the most substantial obstacle to media reforms comes from the military. Contrary to the rhetoric of reform, the military has attempted to consolidate its control over the media and enhance its capacity to block negative coverage of its activities. Reporting on the military largely remains off limits, and the army exercises control over the internet with frequent shutdowns. Former regime figures still control a large share of commercial media, including most of the daily newspapers, and are opposed to any reforms that might jeopardize their interests. In such a context, self-censorship remains the norm in newsrooms, and the government receives preferential treatment. The most recent developments, with the military taking full control of the government in a coup d’état on October 25, 2021, may well signal a closing of the opportunity window for reforms, as the junta is likely to move swiftly to consolidate its power, including its control over the media.

The reforms in Tunisia were far more ambitious and consequential than was the case in Burma, Ethiopia, or Sudan. As of 2015, Tunisia was the only Arab country to be rated “free” in the annual Freedom in the World reports published by Freedom House, until it was downgraded to “partly free” in 2022.23 Deregulating the media sector initially created an explosion of new print publications, but by 2021 only 50 remained in regular publication. During the same period, other media types, such as broadcast media, almost tripled.24 Media were free to debate political topics without major obstacles. However, despite impressive progress, “journalists continued to face pressure and intimidation from government officials in doing their job, especially in the coverage of topics and events related to security forces.”25

The media reform process in Tunisia included broad consultation with civil society, interest groups, and various international actors. In 2011, three key laws were adopted: The repressive press code was replaced by a decree that stipulates freedom of expression, freedom of publication, and right to access and disseminate information. It also eliminates license requirements for print media, introduces anti-monopoly provisions, and abolishes prison sentences for offenses that may arise while performing journalistic duties. A second decree ensures freedom of the broadcast media and institutes an independent regulatory agency for the broadcast sector. The third grants the right of access to information. Constitutional changes in 2014 guaranteed freedom of opinion and expression and the right to access information. Government control over media was severed, including the abolishment of the Ministry of Communication. Important advancements have also been achieved in reforming the state broadcasters into public service media.26

Although some of the reforms championed in Tunisia are considered among the most progressive in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, they still faced significant obstacles in the implementation phase. Most notably, the broadcast regulatory agency encountered hurdles even before its inception, as its creation was delayed for years. Since its establishment, it has continuously struggled to assert itself. For example, several private television (TV) stations continued operating without licenses for years, as political interests prevented regulatory enforcement. In other instances, such as enforcement of media funding transparency, it has encountered persistent opposition, including from the Tunisian Central Bank, which has refused to provide requested information on media finances. Similarly, the public service broadcaster (PSB) faces continuous challenges to its editorial independence and operations. It suffers from frequent attempts by successive governments to reestablish control over it, while struggling with internal organizational issues and a lack of financial resources. Most notably, government officials continue to interfere in the appointment of senior staff. There is also a persistent refusal of executive bodies to comply with the Right to Access Information Law. Moreover, the penal code still criminalizes defamation of public officials and restricts speech on the grounds of “good morals.”27 The political interference in media content is often covert, facilitated through biased reporting of co-opted journalists. Consequently, the media sector is characterized by increasing political polarization, and reforms have stalled, due in large part to the systematic obstructions from media barons linked to the old regime.28 Media are largely owned by politically engaged or affiliated businesspeople, and several state-wide TV channels have links with politicians or political parties. The fluctuating ownership of these channels and lack of transparency over how they are funded undermines the development of an independent broadcast industry.29 How the media system will adjust to the change in political dynamics after the power grab by President Kais Saied in July 2021, in what critics describe as a coup, remains to be seen.30

Compared with other countries covered by this study, Ukraine, having started its political transition in 1991, has experienced the most successful and expansive media reform efforts. In principle, Ukraine has one of the most liberal and plural media systems when compared with other member countries of the former Soviet Union.31 Beginning in 1999, following an agenda set by the Council of Europe, Ukraine undertook many reforms corresponding to the democratization phases of the country. The reform agenda was framed as a comprehensive call for implementation of European standards and best practices pertaining to audiovisual media, transparency of ownership and funding, and financing of the public service broadcaster (PSB). Several of these reforms were largely successful. Most notably, access-to-information laws and decriminalization of defamation have been adequately implemented.

Privatization of state-funded print media is also considered a success in Ukraine, but newly privatized media have struggled to produce quality content or achieve financial sustainability, remaining largely dependent on subsidies from the government or grants from donors. Similarly, transparency of media ownership was a partial success—the names of the broadcasting media owners are now officially made public—but there is no application of antitrust mechanisms to the oligarch-owned media businesses, mostly due to a lack of effort by the Ukrainian Antimonopoly Committee. The PSB transformation efforts succeeded in creating a new institutional and organizational framework for its operations, while effectively eliminating state control over its editorial policy. Nevertheless, the major obstacle to the development and operation of a PSB is underfunding. The only priority reform area without tangible results so far is the adjustment of the audiovisual media services legislation and the implementation of the Audiovisual Media Services Directive,32 where no legislative act has been adopted yet due to conflicting interests of a range of stakeholders, not least the media oligarchs who prefer the status quo.33

Nevertheless, as noted in a 2020 Reporters Without Borders report, the progress achieved is fragile due to oligarchs’ interests,34 weak legal protection of journalists under threat,35 and challenging market conditions that do not provide sufficient sources of funding for independent media. Namely, “most of the country’s outlets are privately owned by high-profile Ukrainians who tend to use them for political influence”36 while only a small fraction of media outlets, which are often donor funded, adhere to standards of professionalism and ethics.37 Consequently, although Ukraine has a relatively open and vibrant media sector, it was classified as “partly free” in the 2020 Freedom House report and ranked 96th in the 2020 World Press Freedom Index by Reporters Without Borders.38

Although this brief overview of media reforms in the five countries points to significantly different experiences and outcomes in their democratization attempts, there are important lessons that can be drawn from analyzing their shared challenges. Commonly, societies in democratic transition will embark on a series of institutional reforms in the journalism sector that align with the best international standards but often fall short in their implementation.39 There seems to be a mismatch between “the quality of the legislation and its practical consequences,” which can often be explained by an implementation deficit that, in some cases, results from deliberate obstruction by local elites.40 The independence and sustainability of new and fledgling institutions is undermined by a lack of political willingness to reform, fragile state institutions, weak rule of law, and financial constraints. These obstacles stymied efforts to advance independent media in all five countries covered by this study. The situation is even more challenging in countries with high levels of political instability and where the military plays a decisive role in the reform process.

The Perils of a Weak State

All of the countries in this study have significant weaknesses pertaining to the functioning of state institutions and the rule of law. Such weaknesses present a challenge for successfully sustaining and executing reforms of the media sector that can help propel the democratization process.

Three countries included in the study are on the United Nations (UN) list of low-income Least Developed Countries—Ethiopia, Sudan, and Burma.41 These countries are characterized by low levels of education, life expectancy, and per capita income and are highly vulnerable to economic shocks. Moreover, according to the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators, Burma and Sudan have extremely low levels of government effectiveness. The situation is similar in the rule-of-law category, where only Tunisia performs notably better. Corruption is a significant problem in all five cases.42

Three countries included in the study are on the United Nations (UN) list of low-income Least Developed Countries—Ethiopia, Sudan, and Burma.41 These countries are characterized by low levels of education, life expectancy, and per capita income and are highly vulnerable to economic shocks. Moreover, according to the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators, Burma and Sudan have extremely low levels of government effectiveness. The situation is similar in the rule-of-law category, where only Tunisia performs notably better. Corruption is a significant problem in all five cases.42

With vulnerabilities to corruption, coercion, and state capture, weak states can struggle to maintain the political will needed to foster media independence and pluralism. This results in political reversals, where legal victories in favor of media development are rolled back or stalled. Even when legal or policy reforms are enacted, weak public administration and rule of law are significant barriers to the successful implementation of democratic reforms, resulting in an implementation gap. Finally, weak states are often poorly equipped to reign in powerful private actors in the media sector, who can be spoilers of media reform efforts. The situation is even more challenging in countries with high levels of political instability and where the military plays a decisive role in the reform process.

These obstacles stymied efforts to advance independent media in all five countries covered by this study, as well as by other countries undergoing similar transitions.43 In Ethiopia, persistent political, administrative, and financial capture of the media by the ruling elite undermined the impact of institutional reforms during the initial opening.44 Despite Tunisia having undertaken the most progressive media regulation reforms in the MENA region, democratic consolidation and implementation have been hampered by the weak state, feeble rule of law, a legacy of authoritarian structures, and recapture of the state by old elites.45 Even before the presidential power grab from July 2021 set the country’s democratic progress back, reforms in Tunisia had stalled during the last several years, not least due to the systematic obstruction from the media barons that are linked to the old regime.46 In Ukraine, media oligarchs are among the most important forces sabotaging implementation of reformed laws. Other factors that undermine proper implementation of laws—seen in all five cases covered by this study—are ineffective judiciaries47 as legal insecurity resulting from ambiguous judicial practice weakens adopted laws and undermines newly introduced regulatory bodies.

Ineffective state institutions are linked to weak policymaking capacity. For reform champions who often come from outside of government, such as donors or civil society organizations, a weak state might be either an opportunity or an obstacle for advancing their reform agendas. For example, as in Ukraine following the Revolution of Dignity and Russian invasion in 2014, civil society filled the gap in policymaking capacity and provided much needed expertise and resources to set the reform agenda and push for its implementation. Similarly, Ethiopia’s government introduced a broad consultation mechanism to help shape its policy reforms. An independent expert advisory body was tasked with assisting the government in defining reform priorities and amending laws on governance, the justice sector, media, and civil society. In Sudan, the government initially invited UNESCO to help draft the 2020 Media Reform Roadmap48 but failed to follow up on the proposed reform agenda. After work on the roadmap was completed, it remained unclear who in the government would implement it because of several factors, including constant reshuffling of staff in the relevant ministries.49

Regime openness and the role of the military are key predictors of reform success. In countries where the military continues to play a prominent role after a political opening, the attempted democratization of the political system, including media, appears to be half-hearted at best, such as in Burma and Sudan. The limited media reforms that were attempted in Burma had effectively been annulled even prior to the military coup in 2021. Instead, repression of journalists and media continued and the “legal reform efforts floundered under the country’s first democratically elected government.”50 In other instances, like in Sudan, declared reforms seem to be a public stunt performed to gain some legitimacy on the international stage and move protesters off the streets, at least temporarily until power is again firmly consolidated in the hands of the military junta. For example, former regime figures still control most of the commercial media, including most of the 18 daily newspapers, and are opposed to any reforms that might jeopardize their interests.51 Sudan did not even properly attempt to implement “most of the institutional and law reforms called for in the August 2019 constitutional charter,”52 including reforms of the security sector, let alone media reforms.53 In Ethiopia, the ruling party retained a firm grip over the most influential media, leaving few opportunities for the development of a genuinely independent media sector.54

Market conditions are highly unfavorable for independent media in all five cases. However, market constraints are amplified by the role of the government, resulting in hostile financial conditions for the operation of independent media. In Burma, weak media markets, distribution monopolies, and unfair allocation of public advertising to government- and military-owned media have hampered the development of viable business models for independent media outlets.55 In Ethiopia, governments at the national and regional levels provide direct budgetary support to public media institutions, while granting them preferential access to advertisement revenues from state companies, limiting media diversity.56 The media in Sudan have been under severe economic stress because of high inflation, which reached 230 percent in October 2020, and dwindling advertising revenues. Moreover, the transitional government continued to direct government advertising toward media outlets close to the previous regime.57 Tunisia’s advertising market is highly politicized and dominated by a few large broadcasters. Such a context puts media and journalists in a precarious position, where financial sustainability is offered in exchange for political loyalty.58 Ukraine has already achieved notoriety for the dominant role oligarchs play in its media market. Thus, recent attempts to introduce an anti-oligarch law have not been successful, while the “antitrust mechanisms do not apply to the media market, which is dominated by four large media groups with political affiliations.”59

Underdeveloped markets and political pressure, combined with obscure media ownership, provide fertile ground for media capture, political patronage, and clientelism: “Exacerbated by the economic weakness of the traditional news business and the growing concentration of ownership of media industries, media capture has become one of the major tools for undermining democratic societies and handing them over to authoritarian rule.”60 Media capture results in the dominance of news outlets beholden to the interests of politicians, their cronies, and business elites, whose main tasks are to undermine public debate, stifle criticism of the ruling party, and consolidate control over the media.61 In all five cases in this study, media capture— by oligarchs (Ukraine, Tunisia), political parties and governments (Ethiopia), or the military (Burma, Sudan)—is a dominant feature of the news system.

The Importance of a Strong Civil Society

The nature of civil society in each of the countries studied varies greatly. In countries that experienced political openings earlier, or where the old regime allowed for at least some level of independent civic life, civil society has proven to be much more advanced in terms of organizational capacity and its potential for collaboration. Across the cases examined for this study, the relative strength and capacity of civil society is an important determining factor for the success of media sector reforms.

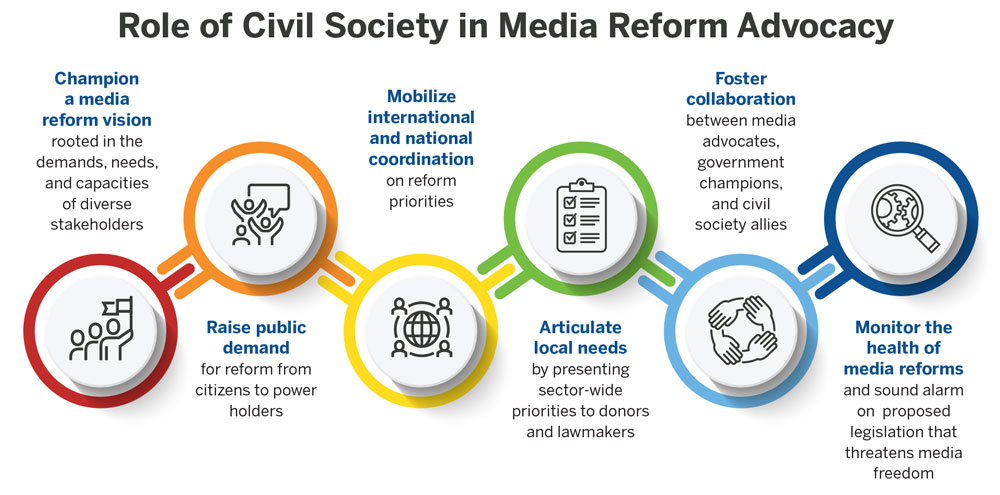

In contexts where the international community helped bolster the legitimacy and effectiveness of civil society in advance of a political opening, more significant reforms were possible. Civil society actors play an especially important role in countries with weak states. They can help sustain political will for reforms, contribute to more effective policies, and find solutions to the implementation gaps experienced in many media sector reform projects.

The Role of Civil Society Coalitions and Movements

Civil society’s influence on the media reform agenda in each of the countries in this study has largely been determined by the strength of the civil society organizations themselves. In countries where civil society is weak, media reform has been anemic at best.

For instance, Sudan’s underdeveloped civil society has played only a minor role in attempts to democratize the media system, and media reform movements and coalitions are virtually nonexistent. This is because civil society was systematically stifled under the previous regime and had little time to develop given the recency of the political opening in the country. Consequently, civil society organizations working on media issues are scarce and severely constrained by a lack of capacity and resources. It is not surprising that after three decades of repression, and with limited resources, civil society organizations in Sudan are finding it difficult to lead the media reform process— “a true bottom-up approach, with the involvement of local Sudanese grassroots media and media-support organizations, has been missing.”62 The civilian arm of the transitional government has been largely unresponsive to several civil society organizations that have tried to engage it.63

In Ethiopia, civil society organizations working in human rights, as well as media and journalists’ associations, have had more involvement in the media reform effort than in Sudan, but involvement is still limited. Civil society in the country is severely underdeveloped because of decades of repression.64 It was only in 2019 that the basic legal framework for the operations of civil society organizations was revised to allow for easier access to international funding and to remove repressive measures that have restricted media as well as political and civil rights.65 Consequently, Ethiopian civil society organizations are in the early stages of development, lacking basic capacity for normal operations.

The Ethiopian government was initially proactive and ambitious, setting up a broad consultation mechanism to help with policy reforms. An independent expert advisory body was tasked with helping the government define reform priorities and amend laws on governance, the justice system, media, and civil society. The technical work of consulting with stakeholders and drafting recommendations and laws was performed by more than 160 volunteer experts, stakeholder representatives, and activists, organized in a number of working groups, including the Media Law Working Group.66 The civil society working group in Ethiopia was important as a way to ensure that a platform for setting priorities existed outside of the government, and that it was led by civil society. Despite this initial success, progress has been slow and halting.

The experiences of Sudan and Ethiopia are in sharp contrast with the prominent role of civil society in reform processes in Burma, Tunisia, and Ukraine. In Burma, civil society actors engaged in wide, cross-sectoral coalitions, playing a crucial role in formulating and maintaining a media reform agenda through the decade of political opening from 2012 to 2021. As the military loosened its grip on society starting in the early 1990s, civil society organizations worked under the radar for two decades, emerging into the public sphere only after 2010.67 The history of prolonged underground engagement in Burma can explain the broad scale of activism of CSOs during the period of political opening.68 By 2012, Burmese civil society organizations planned and built cross-sectoral alliances to advocate for revising and repealing laws that repressed journalists and human rights defenders.69 Hundreds of media and civil society activists organized numerous campaigns and protests in subsequent years. In early 2016, for example, 36 nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) with strong links to international donors established the “Right to Know” working group to engage civil society and the broader population in the process of drafting a right-to-information law. Similarly, the digital rights coalition emerged the same year when a loose network of young activists started a campaign to reform the Telecommunications Law, which was used to arrest activists for posting content that authorities deemed unacceptable. The digital rights movement was characterized by its multistakeholder approach and cross-sector collaboration, and it benefited from international financial and expert support.

Both initiatives ultimately failed to achieve their goals, as the government did not keep its promise to amend the laws deemed undemocratic. But the real value of the initiatives was in bringing civil society organizations together and building their advocacy skills, social capital, and capacity for collective action. The value of these achievements is most vividly evidenced in the wake of the 2021 coup, when this broad network of digital rights activists “managed to move quickly underground while continuing to provide support to media, civil society, and elected parliamentarians”—an impressive legacy of five years of collaboration, advocacy, and activism.70

Tunisia has a robust civil society that proved essential in toppling the Ben Ali regime in 2011 and facilitating a broad set of institutional reforms afterwards.71 The Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet72—a group of four civil society organizations—even won the 2015 Nobel Peace Prize “for its decisive contribution to the building of a pluralistic democracy in Tunisia in the wake of the Jasmine Revolution of 2011.”73 A robust display of civic capacity for reforms during and after the 2011 Jasmine Revolution testifies to decades of work by mainstream and alternative segments of  civil society. The broad lobbying movement for media reforms, led by Tunisian civil society, including the Union for Journalists, managed to bring together national and international players and persuade the government to endorse proposed reforms. However, over time, the broad coalition of civil society organizations that helped push through the media reforms became more informal, mostly surfacing when there has been a need to respond to government repression of the media to organize mass protests and petitions.74 For example, when the government recently appointed a director of the official news agency, Tunis Afrique Presse, a strike by the agency’s journalists, with support from the Union for Journalists, forced the new director to resign.75 Civil society is thus considered the custodian of the political and media reforms in Tunisia.76

civil society. The broad lobbying movement for media reforms, led by Tunisian civil society, including the Union for Journalists, managed to bring together national and international players and persuade the government to endorse proposed reforms. However, over time, the broad coalition of civil society organizations that helped push through the media reforms became more informal, mostly surfacing when there has been a need to respond to government repression of the media to organize mass protests and petitions.74 For example, when the government recently appointed a director of the official news agency, Tunis Afrique Presse, a strike by the agency’s journalists, with support from the Union for Journalists, forced the new director to resign.75 Civil society is thus considered the custodian of the political and media reforms in Tunisia.76

Finally, since the collapse of the Soviet Union and independence in 1991, Ukraine’s civil society has gradually evolved, creating preconditions for meaningful and organized citizen participation in political life.77 Ukrainian civil society has played an important role in keeping a reform agenda alive throughout a protracted and volatile transition process since 1991, and played a fundamental role in Ukraine’s democratization during the 2004 Orange Revolution78 and even more so in the context of the 2014 Revolution of Dignity.79 Civil society contributed to the creation of the national broadcasting regulator in 1994 and the decriminalization of defamation in 2001. This was followed by increased engagement of journalists and media-based civil society in addressing informal censorship during the 2004 “journalists’ revolution,” which preceded the Orange Revolution.80 In 2010, approximately 200 media representatives and activists established the “Stop the Censorship!” movement with the aim “to stop pressure on journalists to censor their content and to push for the adoption of legislation guaranteeing free access to information.”81 The introduction of the Law on Access to Public Information in 2011 indicated the important evolution of civil society advocacy strategies that focused on galvanizing broader public support for reforms while engaging the government more intensively.

Most importantly, civil society was instrumental in launching a comprehensive set of reforms that Ukraine undertook after the Revolution of Dignity. In 2014, a broad cross-sectoral coalition emerged—called the Reanimation Package of Reforms, or RPR— eventually comprising more than 80 civil society organizations divided into 23 sectoral groups, including the media sector, with the aim to push for a broad set of reforms needed to bring the country closer to the European Union. Between 2014 and 2019, the parliament of Ukraine adopted more than 80 laws proposed by RPR experts. An important component of the RPR strategy was getting their members elected to the national parliament in 2014, establishing a direct link between the RPR and the decision-makers, which proved to be vital in catalyzing the drafting and adoption of policy reforms.82 In Ukraine, civil society involvement in the reform processes was much more successful than in the other countries, where authoritarian legacies and a lack of political will for reform stymied coordination and advocacy efforts.

The five case studies in this research demonstrate that, although civil society is crucial for the success of reforms, sometimes deficits in the sector are a significant stumbling block. These deficits pertain to an unsupportive political context, lack of financial viability, limited institutional capacities and leverage, and an often fragmented and politicized journalism community. For example, in Ethiopia, political instability caused by the civil war, as well as a lack of trust in civil society due to years of political interference by authoritarian leaders, impeded civic activism and collaboration. In Ukraine, civil society organizations continue to face significant challenges related to financial sustainability and remain largely dependent on donors.83

The Role of Self-Regulatory Bodies and Media Sector Associations

Self-regulatory bodies such as press councils and professional organizations such as journalists’ associations and unions, as a part of civil society, can play an important role in media reform efforts. If effective, these professional organizations provide much needed demand-side support for reform initiatives and can be seen as one of the main mechanisms for anchoring media reforms into local contexts. They can also act as major agents of change by helping to develop journalists’ capacities through training, promoting ethical and professional standards, advocating for institutional reforms to safeguard media freedoms, and providing legal and other forms of support to journalists facing prosecution and repression.84 In addition, they can provide expertise that is often lacking among policy decision-makers to help during the early stages of policy formulation and can also play an important role in monitoring the implementation of media policy. At their best, journalistic professional organizations play a key role in building and steering civil society coalitions for media reforms and are among the most active organizations when it comes to protecting media freedoms, providing legal and other support to journalists, and advocating for policy reforms.85

While they can be critical to the success of a media sector reform project, self-regulatory bodies, journalists’ associations, unions, and guilds are also vulnerable to capture and sabotage by the broader media sector and political field. They can be sites of polarization and infighting that can hamper, rather than catalyze, collective action to improve the media sector. As such, international cooperation with these bodies must also provide forms of support that bolster their internal governance and strengthen their legitimacy as representatives of the sector. At the same time, these bodies must preserve enough independence from their members to enable them to serve as trusted stewards of ethics and professionalism in the sector.

In all five countries studied, professional journalists’ associations and organizations, such as press councils and unions, are a crucial part of the civil society sphere. They not only advocate for better working conditions for journalists, but also push for broader media reforms and help shape nascent democratic institutions. The five country studies demonstrate the importance of such professional organizations for democratic transitions, albeit to varying degrees depending on context.

In Sudan, the Sudanese Journalists Network (SJN) was an important part of the Sudan Professional Association, which was crucial in the protests that brought down the Al-Bashir regime. The SJN acts as “an alternative to the state-sponsored and controlled journalists union, the Sudanese Journalists Union,”86 and is engaged in campaigns for media reforms and protection of rights of journalists in Sudan, while cooperating with prominent international partners, such as the Committee to Protect Journalists and Reporters Without Borders.87 In Tunisia, the Union for Journalists is widely considered to be among the key champions of media reforms. The self-regulatory body, the Press Council, established in 2020, is also asserting its relevance for media reforms, helping to improve the quality of journalism and promote ethical codes.88 Finally, in Ukraine, a self-regulation framework developed thanks to the engagement of a broad set of actors, including civil society, media organizations, independent experts, and activists, as well as associations of local and regional media outlets and the public service broadcaster. Two relevant self-regulatory bodies with complementary mandates co-exist in Ukraine—the Commission on Journalism Ethics and the Independent Media Council—dealing with issues such as violations of journalists’ rights and professional standards.

In Ukraine, civil society involvement in the reform process was much more successful than in the other countries. This was the result of a prolonged period of trial and error and much effort aimed at capacity building for individual CSOs and broader cross-sectoral networks. Hence, Ukraine has benefited from a robust architecture to support reforms and broad consensus on media sector priorities. The political environment in Ukraine was also generally more conducive to reform. Burma also had a robust civil society that facilitated the democratization agenda, but in contrast to Ukraine, it was constrained by the dynamics of a hybrid military-civilian regime. Advocates attempting to push for reform in a largely military-controlled political environment face an uphill battle, and often have limited success. Similarly, the efforts of a robust civil society in Tunisia have been constrained by ongoing political paralysis, and the main political blocks have failed to reach consensus on a reform agenda and the basic principles of democratic governance.

Self-regulatory bodies and professional associations in nascent democracies face several obstacles that undermine their effectiveness. A key challenge is the lack of journalistic professionalism in these contexts, with limited incentives for journalists to support the activities of self-regulatory organizations. In Burma, for example, the problem with the lack of professionalism has manifested as strong ethnic bias in reporting. In Tunisia, journalistic practice is “hybrid, bringing together features of both democratic and non-democratic regimes,”89 and the high level of dependence on political and business interests has created widespread self-censorship and “journalism of public relations.”90 The unfavorable economic conditions in transitional countries, low pay and precarious working conditions for journalists, and pressure from politicians and media owners pose formidable obstacles to the development of independent journalism.

Similarly, the broader media sector, and in particular larger media businesses, might not be interested in supporting self-regulatory frameworks and activism to bolster independent media. In Ukraine, for example, although the self-regulatory system has been developing for years, the broader media sector has not been very active. There are many reasons for this. Most notably, the absence of regulatory pressure disincentivizes any attempts to introduce mechanisms for settling disputes through self-regulation. Another reason is that Ukrainian journalists are poorly organized, and the effectiveness of the two existing unions—the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine and the Independent Media Trade Union of Ukraine—has been called into question. As a rule, owners’ interests and financial incentives come before any ethical or professional considerations.91 Such a broad set of problems is common in other countries and regions. For example, throughout the Western Balkans, journalists often do not subscribe to the authority of self-regulatory bodies and professional codes of conduct.92 A similar situation exists in the MENA region, where countries have introduced but failed to implement codes of ethics for journalists.93

Finally, underdeveloped capacities of professional organizations limit their impact and relevance in media reform processes. In Ethiopia, a sector-wide media self-regulatory system is a recent development and is struggling to make an impact due to weak legitimacy, absence of stakeholder consensus, and fragile institutional capacity.94 Similarly, Ethiopian journalists’ associations suffer from internal governance issues, such as a lack of accountability, coupled with government interference and co-optation, further undermining the professionalism of journalism in the country as journalists do not trust such organizations.95 In Sudan, political divisions are reflected in journalists’ associations, so that the Sudanese Journalists Network, which took part in protests to topple the Al-Bashir regime, is counterposed to the state-controlled Sudanese Journalists Union.96 In Tunisia, the Press Council, although considered to be the key player in media reforms, lacked a budget and a headquarters two years after its founding.97

For all the above reasons, investments in CSO capacity and organizational support during a political opening are critical to the success of a reform movement and the advancement of a viable and well-functioning media sector. However, such support must be fine-tuned to the local context, and above all else be robust and long term.

The Role of International Assistance

Critics argue that international media support can be least effective when it is most needed, and the rush of donors to a newly opened country can exacerbate the very problems donors aim to address. Many aid recipients argue that donors have all too often prioritized state media development and foreign policy agendas over local ownership and decision-making.98 Donors have also been criticized for prioritizing supply-driven solutions that are not attuned to local dynamics and lack the endurance, coordination, and flexibility necessary to support reformers effectively.

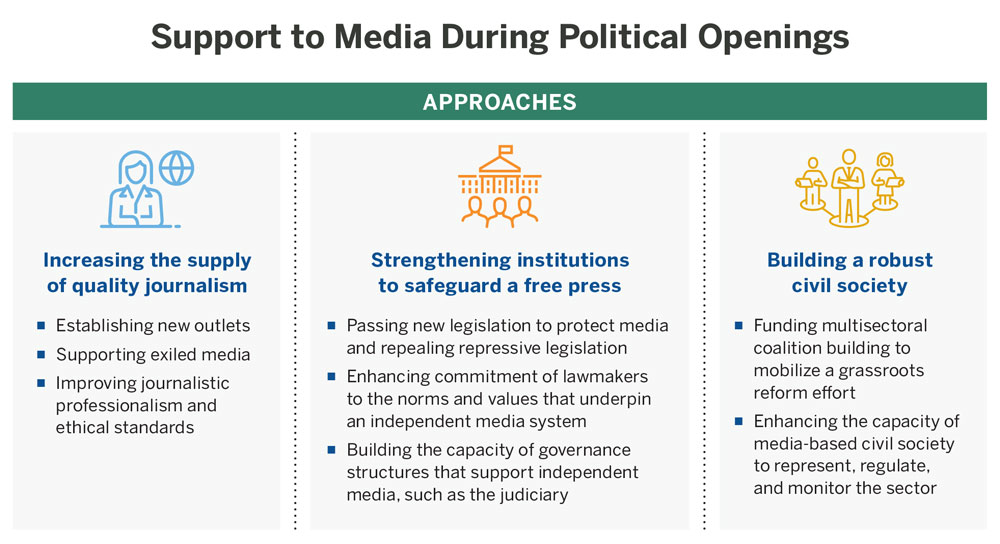

Media development assistance has focused for the most part on training for journalists and other sector-level technocratic interventions. The more expensive, politically charged, and difficult policy reforms—developing the technical capacity of governments to ensure a fair and open media marketplace, promoting transparency of ownership, or reforming state broadcasters—have largely been ignored.99

Media development assistance has focused for the most part on training for journalists and other sector-level technocratic interventions. The more expensive, politically charged, and difficult policy reforms—developing the technical capacity of governments to ensure a fair and open media marketplace, promoting transparency of ownership, or reforming state broadcasters—have largely been ignored.99

International assistance actors in the five countries covered by this study have often struggled to be effective when deploying their media development strategies. There is evidence from the case studies that international assistance efforts were sometimes poorly coordinated, misguided, or mistimed. In Burma, while some media development efforts supported grassroots civil society mobilization, others overestimated the commitment of the state to reform media and supported government-owned outlets. Others pressured exiled journalists to return to the country, where they were targeted and harassed for their independent reporting.100 In Sudan, only limited aid has focused on the media sector since the country’s democratization period began in 2019. Ongoing instability in the country, uncertainty about the future of the transition, and a lack of political will on the part of the government have made donors reluctant to support media.101 Similarly, in Ethiopia, promising early efforts have largely faltered. A media reform process was quickly established between government and civil society, and a media law working group initiated a grassroots, consultative process to set reform priorities. However, international funding for these efforts was largely absent in the early transition period when priorities were established, and the urgency of reforms has been replaced by ongoing instability and conflict.102

Nevertheless, evidence shows that not all strategies have resulted in failure, and notable successes have occurred when approaches have been aligned with the opportunities and constraints in each country. The case studies in this research demonstrate that international assistance to the media sector is crucial to advancing the efforts of reformers during political openings. Foreign aid has provided an important impetus for change, and media assistance has helped journalists and activists navigate rapidly changing social and political landscapes.

Supporting the supply of quality journalism is usually the first line of international assistance to the media sector in early phases of political openings. All of the five countries covered in this report have benefited from donors’ technical assistance programs to the media sector. For example, Tunisia’s media sector received significant provisions of technical media assistance, especially in the wake of the 2011 uprising.103 Ukraine also benefited from technical assistance programs focusing on direct support to independent media outlets and provision of quality journalism. In Sudan, trainings covering a variety of topics, such as professional journalism or business management, have been offered. In principle, and especially during the early phases of a political opening, increasing the supply of quality journalism and journalistic capacity is at the top of donors’ agendas.

In some cases, donors find ways to support independent journalism through technical assistance prior to the actual political transition, providing a critical lifeline. Moreover, the donors who were engaged in the country before the political opening were better placed to provide support when the opening occurred. This is done either by funding exiled media, working under the radar while helping local groups in their communication efforts, or through international broadcasters like the BBC World Service (United Kingdom), Deutsche Welle (Germany), and Voice of America (United States). The focus of such efforts is on improving the supply of independent journalism by helping to form new media outlets outside the country and, when possible, providing funding for content production and journalism training to independent media operating inside. This was the case in Burma, where “whispered support” was provided to independent media and civil society before the 2010 opening.104 In Sudan, prior to the 2018 uprising, a number of international NGOs, such as Internews, GISA Group, Free Press Unlimited/Radio Dabanga, and the Thomson Foundation, provided support below the radar to independent media, mainly in the form of training, as foreign funding of media was restricted by law.105 Similarly, in Ethiopia, International Media Support and Fojo Media Institute were able to provide early support in Ethiopia in part because they had started a project there in 2016.

In some cases, donors find ways to support independent journalism through technical assistance prior to the actual political transition, providing a critical lifeline. Moreover, the donors who were engaged in the country before the political opening were better placed to provide support when the opening occurred. This is done either by funding exiled media, working under the radar while helping local groups in their communication efforts, or through international broadcasters like the BBC World Service (United Kingdom), Deutsche Welle (Germany), and Voice of America (United States). The focus of such efforts is on improving the supply of independent journalism by helping to form new media outlets outside the country and, when possible, providing funding for content production and journalism training to independent media operating inside. This was the case in Burma, where “whispered support” was provided to independent media and civil society before the 2010 opening.104 In Sudan, prior to the 2018 uprising, a number of international NGOs, such as Internews, GISA Group, Free Press Unlimited/Radio Dabanga, and the Thomson Foundation, provided support below the radar to independent media, mainly in the form of training, as foreign funding of media was restricted by law.105 Similarly, in Ethiopia, International Media Support and Fojo Media Institute were able to provide early support in Ethiopia in part because they had started a project there in 2016.

A significant segment of technical assistance is directed at supporting the financial sustainability of media outlets or media-based civil society organizations. This is particularly important during transitions when media markets are often captured by government interests. In these contexts, media markets are underdeveloped and politically polarized, and trust in the media among the public is low, creating virtually impossible conditions for the sustainability of small, independent outlets. In Sudan, for example, independent media suffer from grave economic circumstances, and direct financial support to journalism is a top priority.106 Beyond direct financial assistance, donors support other activities, such as business training to boost the financial sustainability of independent media. In Ukraine, several donor-funded programs after 2014 emphasized improving the management capacities and business models of news outlets, which was important to provide an alternative to oligarch-controlled and politically captured media.107

As some of the country cases illustrate, supply-driven approaches can and do serve a dire need for high-quality, impartial information when there are few options for independent media. Yet such interventions also have several limitations. International assistance to exiled media during the pre-transition military regimes of Burma and Sudan was criticized because the funds did not always reach people inside the targeted countries.108 Programs focused on journalism training are often ill-suited for the context of some countries and do not result in much real change in journalistic practice. As In the case of Ukraine, Mark Nelson argues, “much of the support has been in the form of training, technical assistance and other supply-side approaches…by most measures, it produced disappointing results.”109

Technical assistance in Tunisia also received its fair share of criticism. A lot of donors supported short-term training initiatives that did not correspond to local needs and thus had little impact on professional standards, even though improving the quality of professional journalism was a priority among local stakeholders.110 Similarly, while improving professional standards is a priority for local stakeholders in Ethiopia, the short-term trainings that donors provided were “criticized for being ineffective, misfocused and uncoordinated.”111 Supply-driven approaches, as demonstrated in these case studies, tend to be short term, piecemeal, uncoordinated, and lack a vision of reform that is in tune with local demands and constraints.112

Technical assistance in Tunisia also received its fair share of criticism. A lot of donors supported short-term training initiatives that did not correspond to local needs and thus had little impact on professional standards, even though improving the quality of professional journalism was a priority among local stakeholders.110 Similarly, while improving professional standards is a priority for local stakeholders in Ethiopia, the short-term trainings that donors provided were “criticized for being ineffective, misfocused and uncoordinated.”111 Supply-driven approaches, as demonstrated in these case studies, tend to be short term, piecemeal, uncoordinated, and lack a vision of reform that is in tune with local demands and constraints.112

Much of the criticism is well-founded, but the case studies demonstrate that technical assistance is not completely without merit or impact during the often fraught and bumpy road a country faces in its transition to democracy. The cumulative effects of such approaches, while impossible to measure, can offer an entry point for support in a country where the political, social, and economic factors preclude other types of assistance. Support to media that the donors fund and in effect control—like Radio Dabanga in Sudan—is of great importance in countries where there are few independent sources of information at all. In some cases, like in Burma, it is simply quicker and easier to provide technical assistance, particularly for donors that supported independent journalism prior to the opening, while new analyses are conducted and roadmaps and priorities ironed out.113 Furthermore, institutional reforms invariably take much longer, and quick gains can be needed to build public demand and trust in the media. Finally, in some circumstances, institutional reform and civil society engagement may be severely hampered by lack of political will for reforms or other obstacles, or a reform window may close as quickly as it opened. In these cases, providing direct funding and technical assistance to media organizations may be the only option for keeping the lights on.

However, overt emphasis on training and technical support to independent media, important as they may be, is not enough to redress the often-formidable challenges in building a democratic media system in countries emerging from conflict or authoritarian legacy. That is why international assistance has played an important role in supporting attempts at institutional reforms within the media systems of the five countries. Naturally, the scale of involvement and the impacts have reflected the stage of democratization of each country. In countries with limited commitment to reforms, access to international assistance was also limited.

In Burma, for instance, media assistance efforts were hampered by the Ministry of Information’s top-down approach and a lack of commitment in the transitional government for genuine reforms. In trying to gain inroads, donors worked directly with the new government, supporting reform of the state-owned broadcaster. The assumption that state-run media could be transformed despite the government’s lack of commitment to reforms soon proved to be misguided, and major media development actors shifted support away from government-controlled media toward independent media.114

In Burma, for instance, media assistance efforts were hampered by the Ministry of Information’s top-down approach and a lack of commitment in the transitional government for genuine reforms. In trying to gain inroads, donors worked directly with the new government, supporting reform of the state-owned broadcaster. The assumption that state-run media could be transformed despite the government’s lack of commitment to reforms soon proved to be misguided, and major media development actors shifted support away from government-controlled media toward independent media.114

In Sudan, there were limited opportunities for outside actors to support the media reform process from the outset. The media reform window, if it ever opened at all, quickly closed due to internal divisions between the military and the civilian components of the government, constant political restructuring, a dire economic situation, and ongoing conflict. While a Media Reform Roadmap was created through a multistakeholder process shepherded by UNESCO, it proved to be overly ambitious given the limited capacity of the state. Diplomatic pressure was also applied by Western donors, and the Sudanese government committed to creating a national action plan on media freedom as a condition of its acceptance to the global Media Freedom Coalition in 2019. Despite this initial progress, and a great deal of optimism, implementation quickly stalled. The range and complexity of reforms require far stronger state institutions and a stable government committed to making change. In the absence of this, media development actors are supporting efforts to shore up civil society as local advocates work to catalyze demand among the public for media reform alongside broader governance reform.

The media sectors of both Tunisia and Ukraine benefited from international support for institutional reforms during their political transitions. In Tunisia, international media assistance was mobilized quickly after the 2011 revolution, enabling a significant media reform process to gain a foothold. A number of institutional reforms were prioritized, such as support to public broadcasters and the establishment of an independent regulatory body for the media sector.115 Similarly, international aid for institution building after the Revolution of Dignity was critical to advancing independent media in Ukraine. This included funding focused on reforming the public service broadcaster, improving access-to-information laws, privatizing the print media sector, and addressing media ownership issues. Donors were particularly keen to support Ukraine’s transition due, in part, to its strong and vibrant civil society and membership prospects in the European Union.116

However, the institutional reform efforts in both Ukraine and Tunisia demonstrate that this support needs to be long term. In Tunisia, many of the initial victories stalled before they were fully implemented. Donor support may have helped establish the institutions, but the job was in many ways unfinished. Institution and norm building take time. As is amply demonstrated by the example of Ukraine, decades of support, grassroots organizing, and political wrangling were needed to move from a reform vision to implementation.

Recognizing the need for broad-based support to sustainable reforms, international assistance actors have shown increased commitment to “demand-driven”117 reforms in recent years, acknowledging that historically media development efforts have not been sufficiently rooted in the local context. Similarly, the need for bottom-up support is all the more crucial in countries that remain in protracted states of transition after a political opening, where democratic institutions are undermined by entrenched interests, deep clientelist relationships, and state capture.118 In such cases, where focusing on the reforms of formal institutions may have little effect, civil society mobilization provides a better entry point for independent media support.119

In all five cases, there were attempts by international aid organizations to engage with local nongovernmental organizations, formal and informal groups, and coalitions. In Burma, for example, support for media-based civil society prior to the political opening in 2010 was critical for mobilizing action and grassroots demand for media reform. International assistance helped mobilize a strong coalition of activists to counter the top-down media sector roadmap that was being driven by the state under the watchful eye of the military.120 In Ukraine, the Euromaidan protests in 2014 provided an unprecedented window of opportunity for civil society to influence policy agendas. Dozens of civil society organizations across sectors mobilized to create the RPR. Media was a central component of the RPR, and major media development donors and implementers joined efforts with local organizations and government officials working on legal and policy reform. Critically, donors and implementers “embraced the RPR agenda and largely abstained from interfering in the coalition’s plans,” supporting grassroots, localized movements rather than relying on top-down approaches and externally driven reform templates.121