KEY FINDINGS

The global effort to promote open and transparent government creates new opportunities to put media development on the political agenda of countries around the world. This report looks in particular at the structures of the Open Government Partnership (OGP), which in its 2016 Paris Declaration characterized the media as a “crucial force for transparency and accountability.” In an era of democratic backsliding and declining public trust in institutions of all kinds, the need for pluralistic, independent, and high-quality news media has never been more important. Yet even the most democratically minded countries in the world are having trouble creating the laws, policies, and practices to ensure a healthy media system. Can the Open Government Partnership’s multi-stakeholder forums be used to stimulate solutions to some of the most intractable challenges facing independent media?

This report maps the entry points for media reformers in the OGP process, and highlights a series of recommendations for how to take advantage of these entry points, including by:

– Building country-level coalitions that can put media reform on the open government agenda

– Investing in global agenda-building and peer-to-peer learning on the intersections between open government and media development

– Aiming for long-term and strategic goals related to the OGP’s National Action Plans

Introduction

In an era of democratic backsliding and declining public trust in institutions of all kinds, the need for pluralistic, independent, and high-quality news media has never been more important.

Yet even the most democratically minded countries in the world are having trouble creating the laws, policies, and practices to ensure a healthy media system. Meanwhile, international donors and global civil society organizations are also looking for ways to build consensus on the reforms needed to shape media environments around the world. How can countries ensure that their citizens get high-quality, trustworthy, and accurate information on which to base their decisions?

Answering this question meaningfully will require dialogue among civil society, the private sector, the government, and the media sector. Yet few incentives exist at the national level to bridge the growing distrust among these groups. This report looks at how the Open Government Partnership’s multi-stakeholder forums could be used to stimulate the dialogue needed at the national level to find solutions to some of the most difficult and intractable challenges facing independent media.

Can the Open Government Partnership Play a Role?

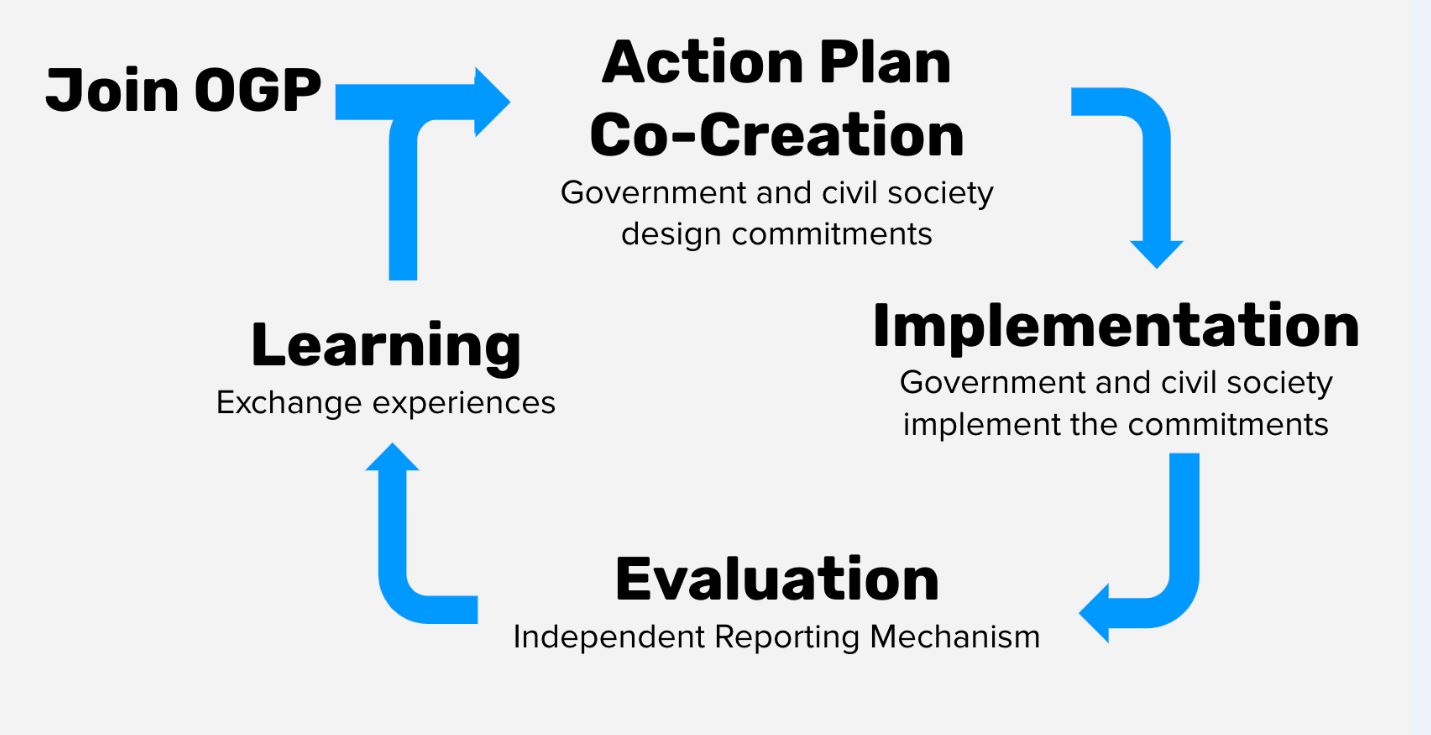

Founded in 2011 by eight national governments, the Open Government Partnership (OGP) is a formalized multi-stakeholder process. Under the OGP, government reformers and civil society leaders come together to create national action plans to make governments more inclusive, responsive, and accountable.1 In its spirit of multi-stakeholder collaboration, OGP is overseen at the global level by a Steering Committee that includes representatives of governments and civil society organizations. At the national level, the OGP dialogue process is driven by the national government and local civil society organizations. Since its founding, the OGP has expanded to nearly 80 countries, which have made over 3000 commitments to open government reforms.2

In many countries, efforts to make government more responsive, accountable, and effective suffer from a lack of political will on the part of public officials and insufficient engagement with civil society and the broader public. The OGP platform was designed to enable this kind of multi-stakeholder engagement at the national level, while building a global community of government reformers and civil society activists. Such a multi-stakeholder approach has repeatedly been identified as vital to the success of international efforts in support of media development.3

The OGP Paris Declaration, endorsed at the Global Summit in Paris in 2016, outlined the membership’s commitment to protect “freedom of expression, including for the press and all media, defend the role of journalism as a crucial force for transparency and accountability, and stand up against attacks and detention of journalists.”4 Despite this commitment, there has been limited activity within the global OGP community to address media as an area for reform, and the media development community has been largely absent from the OGP movement.

There are signs that this is changing. Faced with unprecedented challenges from technology and the global spread of disinformation, governments around the world are starting to recognize that media reforms are critical to their overall development. According to OGP Steering Committee Member, Maria Baron, in Latin America “none of the leading media NGOs are involved in the OGP—but this also means there’s a real opportunity to bring them into the fold.”

For the media development community, the significance of the OGP’s membership is that it represents an important subset of reform-minded countries, with many expressing the will for reform. The OGP platform provides a unique space for structured multi-stakeholder dialogue, provides space and tools for that collaboration, and creates incentives for sustained engagement that could be valuable assets for media reformers.

To be sure, the OGP process not always been successful in tackling the most difficult governance problems. Corruption, public finance reform, and public service reforms for example, require far-reaching changes in the status quo, and compromises by key stakeholders. Such deep-seated governance challenges do not always respond to the structured approach of goal-setting and multi-stakeholder dialogue that the OPG provides. And absent the necessary political will by government and sustained engagement by civil society, the OGP is no more likely to provide a silver bullet for the complex area of media sector.

Yet, many studies of media development have concluded that a more integrated, politically-engaged approach to media reform is needed, while other studies show that successful reforms have almost always required the multi-stakeholder dialogue and agenda-setting.567

This paper will describe how the OGP might be leveraged as a platform for advancing more demand-driven, long-term, and strategic approaches to media development. It will briefly describe the OGP process and highlight entry points and opportunities throughout the process. Finally, it will describe how the donor community, the media development community, and national civil society actors might operationalize efforts within OGP to advance the media development agenda.

Media Development and Open Government

The benefits to society of a well-governed and independent media are numerous.

The benefits to society of a well-governed and independent media are numerous.

With the right enabling environment, media can serve diverse communities as a public intermediary, amplifying citizen voices to facilitate broad public participation, discussion, and debate. Media can also serve as a ‘barometer’ to gauge public opinion, stress-test decisions, and help close feedback loops to government and service providers by elevating issues into the public consciousness for action. Media is also a crucial user and re-user of government data, including demystifying it for massive public access. By enabling the public to voice their priorities and perspectives, the media play a crucial role in helping citizens become more active agents of their own development.

However, in some parts of the world, the media are failing to adequately play this role. Media that is captured by governments or economic interests can distort public debate and create barriers to reform. Governments can see the media as the primary obstacle to their plans, and a growing number of political leaders across the world have resorted to heavy-handed restrictions to control media content.8 At the same time, as the news media has been weakened by the loss of advertising revenues to social media and digital delivery platforms, it has increasingly become subject to capture by wealthy oligarchs who see media ownership as a way to influence public opinion and promote their economic and political aims.9

Addressing these weaknesses in media environments is a governance challenge, and it will require concerted efforts by both governments and civil society to find solutions.

A well-performing media would also provide invaluable feedback to the OGP process overall. It could help increase citizen understanding of what the OGP is doing and how it is helping countries organize their reforms. Just as important, though less recognized, is how reform of the media sector can work hand-in-hand and contribute to reforms in other sectors—such as health, natural resources, and education–by informing the public and enabling broader participation in governance processes.

Rather than erecting barriers to independent media, state actors are needed by the media sector to create a legal and political environment that encourages high-quality news and information, and that promotes the role of independent institutions as critical to social progress. Multi-stakeholder dialogue has been a critical means to achieve such a media system.10 On transparency, corruption, governance, and other issues, the OGP has provided a platform for building such multi-stakeholder strategies. Could it also be used to stimulate the kind of broad-based media reform efforts witnessed at various times in countries such as Uruguay, Namibia, and Indonesia?

While OGP members have demonstrated strong interest in commitments related to access to information and safety of journalists, only a handful of commitments have so far specifically addressed broader governance challenges facing media systems. As earlier stated, media more often appears in national action plans as an instrument for enhancing accountability, transparency, public engagement, and service delivery in support of other areas of reform, but rarely do commitments address media as an area of reform itself. Such an approach centers on improving the enabling environment for media by reforming institutions and legal and regulatory frameworks that govern the media sector. Commitments in this area would address issues such as the allocation of broadcast spectrum, government advertising, ownership and competition, regulatory institutions, public media institutions, and the digital space.

While commitments that address these issues are still a relatively new area for OGP, several countries recently established noteworthy commitments that focus on these media governance questions, including Mongolia, Ghana, Ukraine, Macedonia, and Jordan. These commitments sought to address issues ranging from reform of public service broadcasting and media licensing, ending impunity for attacks on journalists, and ensuring transparency of media ownership. Many leading media reform activists believe there is untapped opportunity to take advantage of the OGP platform to get media on the reform agenda and organize local demand for much needed change in media systems.

According to Nata Dzvelishvili, executive director of the Georgian Charter of Journalistic Ethics and an observer of the OGP process in the Georgia, the OGP could play an important role in dealing with structural problems with the media sector that often go unnoticed by observers, such as transparency around ownership and government advertising. Likewise, Edetaen Ojo, executive director of the Media Rights Agenda and a participant in the national OGP process in Nigeria, has pushed for a media freedom commitment that, among other issues, would reform the country’s press council. “We want a commitment that addresses this issue—that commits to making the press council independent of all political actors. This would be important for media in Nigeria.”

Such demands from media development actors suggest an emerging constituency for work addressing the enabling environment for media, and the potential for more action in this area within the OGP community. Furthermore, engaging the media development community in the OGP process could strengthen the OGP’s country platforms, bringing in new actors and stakeholders vested in keeping governments open.

Entry Points for Media Development within the OGP Process

While multi-stakeholder approaches to reform are not new, the OGP’s structured and formalized process creates a unique arrangement between national governments and civil society. The government commits by agreeing to basic qualifications, creating a multi-stakeholder forum, engaging with civil society, and submitting its steps toward greater openness to independent review.

For civil society, the process provides an opportunity to engage in direct dialogue with government and co-create an agenda for reform. For international donors and other global actors looking to support national-level media reform efforts, it also provides specific entry points to anchor their work and leverage their resources in support of local actors.

In order to understand how the OGP presents opportunities for the international donor community to improve work on media development, it is important to understand how the process works and where specific entry points exist within the process.

Eligibility

Multi-stakeholder dialogues for reform are only productive in countries where the government can demonstrate a basic level of commitment to open government principles. Prior to formally expressing intent to join OGP, governments must pass an eligibility assessment. They are assessed by the OGP steering committee across four areas: fiscal transparency, access to information, asset disclosures, and citizen engagement.11 To join OGP, the countries must score at least 75 percent in this independent assessment, which is based on objective governance indicators using public data sources.

Since late 2017, the OGP Steering Committee has also instituted a “Values Check” eligibility requirement, which is intended to ensure that new countries joining OGP adhere to the democratic governance norms and values set forth in the Open Government Declaration. For the “value check,” OGP uses two indicators from the Varieties of Democracy “Dataset on Democracy”:

- CSO entry and exit: measuring the extent to which the government achieves control over entry and exit by CSOs into public life.

- CSO repression: measuring the extent to which the government attempts to repress civil society organizations.

In addition to the 75 percent threshold for Core Eligibility, aspirant countries are expected to score at least three out of four on at least one of the two indicators.

The eligibility review is the first step in the OGP process that may present an opportunity to emphasize the fundamental importance of independent media for open government. Should sufficient demand for media and press freedom develop as a core theme of OGP work, a case could be made to the steering committee that a baseline level of respect for press freedom should be incorporated into the eligibility criteria. Additional Varieties of Democracy indicators could be considered benchmarks, such as those pertaining to government censorship, freedom of expression, or harassment of journalists.

How Issues Get on the OGP Agenda: The “Co-Creation Process”

Upon confirmation of eligibility and submission of a formal letter of intent, the government is expected to develop a National Action Plan (NAP). The action plan is developed through a multi-stakeholder co-creation process with citizens and civil society. Indeed, by joining OGP, governments endorse the OGP Articles of Governance, which states “OGP participants commit to developing their country action plans through a multi-stakeholder process, with the active engagement of citizens and civil society.”12

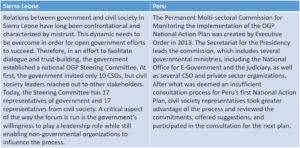

While the OGP does not dictate a formal process for civil society participation, it is strongly encouraged throughout entire OGP cycle.13 The OGP Support Unit, based at the secretariat in Washington, DC, provides significant guidance and best practices for guiding governments and civil society in developing and managing national-level multi-stakeholder forums that oversee the OGP process.14 However, the structure and design of the consultative arrangement is ultimately determined by the government and depends heavily on the national context and the priorities of the stakeholders. Below are two examples of the consultative forums that have been developed.1516

For the media development community, the co-creation process is the first critical entry point in OGP. It is the heart of the OGP process, as it is where government and civil society debate and define the country’s two-year open government reform agenda, the NAP. While getting commitments that relate to the media on the NAP is no guarantee of success, according to Edetaen Ojo, it is still a valuable win for reformers. “Once you get a commitment, the government has to talk about it…it is the first stage of advocacy and acknowledgement that this issue is important. The next piece is implementation.” In other words, a commitment is how media gets on the reform agenda.

NAPs can only accommodate a limited number of commitments, and with the wide range of interest groups competing for space, it is vital that media reform advocates organize themselves, build coalitions, and actively participate in the process. According to several experienced OGP activists, media usually does not make it on NAPs because the right groups are not at the table. Media issues get crowded out by other topics that are backed by better organized and more engaged constituencies.

To influence the co-creation process requires a broad-based coalition of national actors that have a stake in improving the media landscape. Depending on the national context, these actors can include journalist associations, press councils, press freedom organizations, human rights organizations, legal groups, universities, and others that can advocate strongly for commitments that impact the media.

Such coalitions, however, inevitably confront several key challenges. One of these challenges is to prioritize the wide range of issues encompassed in the media development agenda. Indeed, the complex set of issues affecting media systems include topics such as journalist safety, broadcast regulation, advertising markets, internet policy, public sector media, media ownership, and many more. When identifying priority issues, local reformers should identify those issues that are most likely to attract a broad base of support, but also the issues that are most likely to gain traction within the OGP community.

The dialogue around setting priorities and sequencing of reforms can provide a critical way to diagnose the key problems in a country’s media environment. Indeed, many international donors have cited the lack of sector-level diagnostics as a major barrier to their support for media development.17 The multi-stakeholder process encouraged by the OGP helps build ownership of the needed reforms and consensus among key actors.

According to many OGP reformers, another key challenge is the difficulty of bringing an entirely new topic to the frequently crowded OGP agenda. With so many competing interests, media development actors are more likely to succeed by linking media to existing OGP trends and themes, which can both bring media development actors into the fold and build allies among existing constituencies to achieve meaningful reform for the media development community. Existing thematic areas that may present opportunities for media development actors include those focused on access to information, beneficial ownership, open contracting, and civic space.

Tying media to existing priorities can also help better integrate media into broader governance reform efforts, long a challenge for the media development community more broadly. For instance, open contracting and beneficial ownership are both themes with strong existing communities of support within OGP. Within the open contracting movement, media actors can look to address the issues of transparency of broadcast spectra allocation and licensing, while beneficial ownership provides an opportunity for media reformers to address the issue of media ownership transparency laws. Harlan Mandel of the Media Development Investment Fund (MDIF) notes that beneficial ownership laws are not often pursued with the media sector in mind, though these kinds of reforms could be very important for addressing media ownership challenges.

This is not to say that media development actors should only pursue topics linked to existing OGP thematic priorities. But given that media has largely not been a part of the OGP dialogue in most countries, competing for space on the agenda alongside established thematic constituencies may prove challenging in many contexts. As briefly discussed in the next session, without broad-based support and political will, these commitments are unlikely to succeed.

National Action Plans

NAPs are intended to be a reflection of priorities of the participating stakeholders and are at the core of a country’s participation in OGP. They are the product of the co-creation process in which government and civil society jointly develop commitments. Successful OGP action plans focus on “significant national open government priorities and ambitious reforms; are relevant to the values of transparency, accountability, and public participation; and contain specific, time-bound, and measurable commitments.18

Each commitment in a NAP includes a government-designated point of contact, relevant civil society organizations, and a description of the problem that the commitment is intended to solve. OGP-participating countries work in a two-year NAP calendar cycle without gaps between the end of the last action plan and the beginning of the new one. This means every country will be implementing a NAP at all times, although individual commitments and milestones still vary in length.

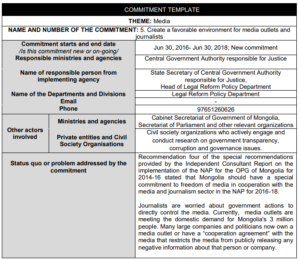

A media-related NAP commitment is a tacit agreement between civil society and the government that media is a reform priority. Having a commitment, such as the one from Mongolia below, is also concrete and measurable roadmap for reform. Although many reforms may require more than the two-year NAP cycle, commitments can be iterative, or established with the expectation that it will continue to be featured on subsequent NAPs.

As discussed in the previous section, the nature of the commitment will depend largely on the approach taken by the media reformers involved in the co-creation process. Local actors must decide whether there is sufficient support and political will to push for a commitment aimed squarely at the media sector, such as the example below, or whether to adapt existing OGP thematic areas, such as open contracting or beneficial ownership, to the media sector.

Mongolia is one of the few OGP member countries with a commitment focused squarely on the enabling environment for media. Through the leadership of civil society organizations like the Press Institute of Mongolia, Mongolia’s 2016 NAP includes the commitment to “Create a favorable environment for media outlets and journalists.” The commitment identifies a lack of media ownership transparency and the need for legal frameworks that encourage and protect pluralism in the media sector. Specifically, the commitment calls for the adoption of a new Law on Media Freedom and reform of the existing Law on National broadcasting, to ensure that they measure up to international standards. In practice, the commitment emphasized public stakeholder consultations in the development and review of proposed legislation. Though a Law on Broadcasting was introduced in late 2016, it has been criticized as failing to meet international standards and questions remain about the level of public consultation and civil society engagement on its development.19

Mongolia’s OGP Commitment (2016-2018) to Improve the Enabling Environment for Media. Source: Open Government Partnership

Similarly, Jordan included a media commitment in its 2016 NAP called “Strengthen the Framework Governing Freedom of the Media,” which was backed by a network of community media actors. However, much like the Mongolian experience, the commitment has not resulted in much tangible progress, with implementation hampered by a lack of political will from the government. Implementation has been a problem for OGP on other issues as well, so the challenges faced in Mongolia and Jordan are by no means outliers. However, the experience of these two countries illustrates how crucial it is to build broad coalitions and think strategically about existing constituencies and opportunities in the OGP community.

Executive director of the Press Institute of Mongolia, Munkhmandakh Myagmar, remains confident, however, that despite the shortcomings in implementation of Mongolia’s commitment to improve the media environment, the OGP platform still provides “a very helpful opportunity to make reform priorities more visible and enables reformers to use the NAP commitments to push the government” to engage with civil society on media reforms.

There is no singular pathway for getting media on the OGP agenda. However, for local actors and the international community, integrating media in the OGP agenda in the form of NAP commitments creates a framework through which local actors can coordinate, organize, and measure efforts at reform affecting the media space. While there is no guarantee of success, NAP commitments can help organize the demand for improving the media space and provide opportunities for international donors, media development organizations, and other institutions to fund locally driven multi-stakeholder efforts for media reform.

The Independent Reporting Mechanism

While the co-creation process and NAP are the backbone of the OGP process, implementation of the commitments is ultimately the most important, and challenging stage. No matter how structured and transparent the process, political reform is difficult. However, monitoring and evaluation is an important part of the OGP process. It helps the government, civil society, and the OGP steering committee identify successes and failures, enable public discussion of the progress, and gives shape to the subsequent two-year NAP.

While the national forums and the stakeholders involved play an active role in monitoring the progress and implementation of NAPs and governments produce self-assessments throughout the NAP cycle, OGP also has an independent reporting mechanism (IRM) that assesses progress toward implementation of the NAP. The IRM is guided by, but not directly accountable to the Steering Committee, and is overseen by an International Experts Panel (IEP). All IEP members are established experts in transparency, participation, and accountability, and play the leading role in guiding development and implementation of the IRM research method and outputs. The IRM plays an important role in providing a clear picture of progress made toward implementation of the NAP and provides an opportunity for civil society to hold government accountable.20

For the media development community, which struggles with measuring and evaluating its impact on the ground, the IRM provides a built-in mechanism for monitory progress toward fulfilling NAP commitments.

How to Get it Done: Leveraging the OGP Platform for Media Development

Throughout the OGP process, international organizations have a variety of ways to leverage their resources to support locally driven efforts get media on the national governance reform agenda. Given that a persistent challenge for the international development community’s work on media development is the duplication of efforts and top-down approaches that overlook local priorities, the OGP provides a platform for the international donor community to anchor some of their media development efforts within locally owned and demand driven reform processes. And while local actors need to drive the work, there are clear ways that the international community can support and reinforce those efforts.

In fact, international organizations, including major donors, have already taken advantage of the OGP process in other areas. As part of their work on broader governance reform in Tunisia, Jordan, and Morocco, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has found the OGP a useful platform for furthering dialogue between civil society and the government on the governance reform agenda. In Jordan, the OECD supported and engaged with a local network of media-focused civil society that helped Jordan become one of the only countries in the world to include the media sector on the country’s third NAP. In Uruguay, UNESCO participated as a neutral observer and facilitator of the country’s effort to draft a second NAP by helping to convene meetings and bring together key stakeholders as a neutral 21

Support Country-Level Coalition Building

A significant body of literature on reform movements suggests that often the most impactful role for outside actors, including international donors, is to play the role of neutral convener, facilitator, and technical advisor.22 Getting media on the OGP national level agenda is a matter of doing just that. By helping to organize the demand, convene local partners, and provide technical expertise and insight, the international donor community can help local actors make the case for media as a national priority in a NAP.

For international donors, taking advantage of the OGP platform can begin by identifying the existing programmatic work that could be strengthened by engagement in the national OGP process. For example, if a donor is working on community radio in a given country, significant challenges in the operating environment might include problematic licensing laws, or high barriers to entry. The national OGP process could provide a way for the donor and local partners to address challenges that could help improve their existing programming. In another example, a major challenge in Tunisia is that the country’s only journalist training institution remains weak, hampering the development of quality journalism in the country. By mobilizing local groups in Tunisia, donors and other outside groups could help engage in the OGP process with a goal of getting a commitment in the NAP to reform and strengthen the government-run training center.

The OGP is a platform with substantial convening power that provides an entry point to strengthen outcomes for media development by organizing the demand for reform. International donors can help local actors take advantage of it by helping them convene local stakeholders and providing crucial technical and policy expertise to help them get challenges facing the media onto the national agenda.

Agenda Building and Peer-to-Peer Learning Globally

The OGP is a national-level process, and any effort to get media prioritized on the global OGP agenda and with the OGP Support Unit must start with organizing local demand in countries. According the former co-chair of the OGP steering committee, Mukelani Dimba, there is a tendency on the part of activists advocating for new issues in OGP to want to lean on the OGP Support Unit to champion causes at the global level with the expectation that this effort will trickle down to the national level. According to Dimba, this approach rarely succeeds.

Instead, getting new areas of work off the ground is better done by organizing demand from the ground up and linking grassroots activity in different countries. When grassroots demand bubbles to the surface at the global level, the support unit is more likely to leverage resources, which includes staff time, funding, and research in support of the issues at hand. It could also move the Support Unit to institutionalize media as a critical area throughout the process, such as in the eligibility assessment, guidance on co-creation processes, or even dedicated Support Unit staff.

While getting media on the OGP agenda requires a bottom-up approach, the value of cross-border networks and a global community of activists is difficult to overstate. Indeed, some of the highest profile thematic areas within OGP benefit from a strong global community that pushes their agenda at the global level, connects activists in different countries, enables peer-to-peer learning, and helps reinforce and strengthen national-level advocacy. For “open parliament” work, for instance, a loose-knit but dynamic global network plays a critical role keeping their issues on the agenda, supporting knowledge exchange, and maintaining it as a priority area for the support unit.

In order to get media onto the global OGP agenda, international donors can help to connect local activists across borders and support peer learning and knowledge exchange about  successes and failures. Gilbert Sendugwa of the African Freedom of Information Centre (AFIC) in Uganda is a leading open government activist. According to Sendugwa, from the beginning he and his colleagues “saw the OGP process as an opportunity for access to information—because it would bring government and civil society together. “With support from the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, we were able to push access to information across the African continent and the OGP process played a very important role in anchoring this work.”

successes and failures. Gilbert Sendugwa of the African Freedom of Information Centre (AFIC) in Uganda is a leading open government activist. According to Sendugwa, from the beginning he and his colleagues “saw the OGP process as an opportunity for access to information—because it would bring government and civil society together. “With support from the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, we were able to push access to information across the African continent and the OGP process played a very important role in anchoring this work.”

More recently, Sendugwa has championed the issue of open contracting within OGP. In order to raise the profile of the topic, Sendugwa and several key partners built a network of reformers interested in open contracting across many different countries. They linked these groups first at regional level, taking advantage of OGP’s regional forums to organize panel sessions and coordinate research. Eventually the network grew robust enough to participate in the OGP’s global summits, and now open contracting is one of the highest profile areas of work on the OGP agenda. According to Sendugwa, “Once you build enough interest across countries as a network, you stand a good chance of getting these issues on the agenda. Ultimately, what’s important is national level activity, but building global networks on an issue helps reinforce and support national level actors.”

Long-term support

The OGP process is cyclical and ongoing. While the NAP’s are two years in length, the process accommodates the reality that political reform can take many years of sustained effort. As a result, OGP requires long-term attention by local actors. For the international donor community, it requires sustained support. Once a NAP is finalized, the difficult work of implementation begins. At this stage, the international donor community and media development actors succeed when their efforts remain coordinated on ongoing multi-stakeholder consultation, research, and knowledge exchange in support of advocacy and reform efforts.

In that vein, the OGP recently worked with the World Bank to establish the OGP Multi-Donor Trust Fund to support OGP members in the implementation of commitments, with a particular focus on OGP’s thematic priorities. Funding will help activities that address technical or financial constraints to implementing NAPS as well as support for cross-country research, peer-to-peer learning, and knowledge exchange. 23If the media development community can engage effectively in the OGP community, it would benefit from the same kind of support for reforms that improve the environment for media and enable the media to play a crucial role in good governance and democracy.

Conclusion

The OGP provides an opportunity to advance more demand-driven, long-term, and strategic approaches to media development. It offers a structured, multi-stakeholder platform for media development actors to engage with government and other civil society groups to confront the challenges facing independent media. It also provides a clearer framework for the international donor community to anchor some of their media development work in local reform processes. While the OGP is not a silver bullet and though its members still struggle with serious implementation gaps, much has been learned about how to use the OGP effectively. Many of these lessons, documented here, can be applied in the effort to integrate media into the OGP platform. Though perhaps just as importantly, much also remains to be learned about how the media sector can be safeguarded as a pillar of transparent, accountable, and effective government. The OGP’s success, amid a crisis in independent media and information, may depend on it.

Footnotes

- “About OGP.” About OGP | Open Government Partnership. Accessed Nov 20, 2018. https://www.opengovpartnership.org/about/about-ogp.

- “About OGP,” Open Government Partnership. Accessed Nov 20, 2018. https://www.opengovpartnership.org/about/about-ogp.

- Ibid.

- “”Paris Declaration,” Open Government Partnership.” Accessed November 12, 2018. https://www.opengovpartnership.org/paris-declaration.

- “Mauersberger, Christophe, Advocacy Coalitions and Democratizing Media Reforms in Latin America: Whose Voice Gets on the Air? (Berlin, Springer International Publishing, 2016).

- “Waisbord, The Pragmatic politics of media reform: Media movements and coalition-building in Latin America. Global Media and Communication 6 (2010). 133-153.

- “Wasserman, Herman and Nicholas Benequista, 2017, Pathways to Media Reform in Sub-Saharan Africa: Reflections from a Regional Consultation (Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance).

- “Nelson, Mark, 2019, Redefining Media Development, International Media Development: Historical Perspectives and New Frontiers, (New York City, Peter Lang Publishin, 2019), 30.

- “Schiffrin, Anya, ed., 2017, Introduction, In the Service of Power: Media Capture and the Threat to Democracy (Washington, DC: The Center for International Media Assistance), 4-5

- “Waisboard, Silvio. “The Pragmatic Politics of media reform: Media movements and coalition-building in Latin America.” Global Media and Communication 6 (2010): 133–153.

- “How To Join,” Open Government Partnership, accessed October 25, 2018. https://www.opengovpartnership.org/about/about-ogp/how-it-works/how-join.

- “Open Government Partnership: Articles of Governance. June 2012. https://www.opengovpartnership.org/about/about-ogp/governance/articles-of-governance.

- “OGP Participation & Co-creation Standards. Open Government Partnership. Washington, DC. https://www.opengovpartnership.org/ogp-participation-co-creation-standards

- “Velasco-Sánchez, Ernesto, 2018, Designing and Managing and OGP Multi-stakeholder Forum: A Practical Handbook with Guidance and Ideas. (Washington, DC, Open Government Partnership)http://www.opengovpartnership.org/sites/default/files/Multistakeholder%20Forum%20Handbook.pdf

- “Ibid

- “Samba- Sesay, Marcella, 2015, OGP Process in Sierra Leone: Engaging in mutually respectful manner and Finding a common ground to actualise the reforms we need. (Washington, DC. Open Government Partnership) https://www.opengovpartnership.org/stories/ogp-process-sierra-leone-engaging-mutually-respectful-manner-and-finding-common-ground

- “Benequista, Nicholas, 2019, Confronting the Crisis in Independent Media: A Role for International Assistance (Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance)

- “OGP Process Step 2: Develop an Action Plan,” Open Government Partnership, accessed November 11, 2018, https://www.opengovpartnership.org/resources/ogp-process-step-2-develop-action-plan.

- “Mongolia Action Plan 2, Open Government Partnership, accessed February 12, 2019. https://www.opengovpartnership.org/members/mongolia/commitments/MN0026/

- “”Independent Reporting Mechanism.” About OGP, (Open Government Partnership). https://www.opengovpartnership.org/about/about-ogp..

- “Velasco-Sánchez, Ernesto. 2018. Designing and Managing and OGP Multi-stakeholder Forum: A Practical Handbook with Guidance and Ideas. (Washington, DC, Open Government Partnership) http://www.opengovpartnership.org/sites/default/files/Multistakeholder%20Forum%20Handbook.pdf.

- “Waisbord, S., 2010, “The pragmatic politics of media reform: Media movements and coalition-building in Latin America”, Global Media and Communication, 6(2), 133–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742766510373718

- “OGP Multi-Donor Trust Fund,” Open Government Partnership, accessed January 20, 2019. https://www.opengovpartnership.org/ogp-trust-fund.