Introduction

In the early hours of February 1, 2021, Burma’s military-owned Myawaddy TV unlawfully declared a state of emergency. Shortly thereafter, the generals seized control of state-owned newspapers and Myanmar Radio and Television. The Burmese military’s decade-long experiment in sharing power with civilians had come to an end.

That state media was the vehicle for spreading word of the military coup was a disappointing if unsurprising outcome for local journalists. It also raised questions for the foreign donors and media assistance actors that had partnered with Burmese state media.1

“We always knew a coup could happen, and that the military would use state media for its propaganda,” said Nan Paw Gay, the founding director and chief editor of ethnic media outlet Karen Information Centre. “What did surprise us is that the international community provided so much support for state media before the coup. State media crippled the private media sector, there was no evidence of concrete reform, and it was always vulnerable to military takeover.”2

For donors and media assistance actors, the Burmese military’s attempt to return to full rule after a ten-year period of political opening is a chance to reflect on efforts to aid media development in the Southeast Asian nation. Current opportunities for continued media development inside the country have greatly dwindled. Aung San Suu Kyi, the country’s elected leader who shared power in an uneasy arrangement with the military, is now in detention as her political show trial unfolds. The coup has escalated the civil war between the military and ethnic minority armed groups into a nationwide conflict, with some ethnic-majority Bamar also taking up arms against the military. Meanwhile, the junta has essentially outlawed independent journalism: raiding news outlets; interrogating, torturing, jailing, or exiling reporters; and barring access for foreign journalists. The few remaining independent news organizations inside the country operate underground or from ethnic minority controlled areas along Burma’s borders.

Despite the grim outlook, media development efforts in Burma between 2010 and 2020 may be instructive not only for donors pondering the way forward, but also for media assistance efforts in other countries in transition. This report, part of the Center for International Media Assistance’s “Media Reform amid Political Upheaval” project, highlights the resiliency and impact of the extensive projects that media assistance actors and donors took in advance of Burma’s 2010 opening. It also serves as a case study in the dangers of supporting captured institutions, such as Burmese state media, when the entities that control those institutions are not committed to a democratic transition. In Burma’s case, the mainstream media reform agenda was guided by influential media development donors that supported government priorities to the detriment of independent journalists and grassroots activists who had an alternative vision for the country’s future.

Finally, this briefing looks at two coalitions that undertook major reform campaigns during Burma’s opening, and draws on interviews from 42 people in the sector to outline principles that donors and media assistance organizations might use to navigate the post-coup environment.

Background

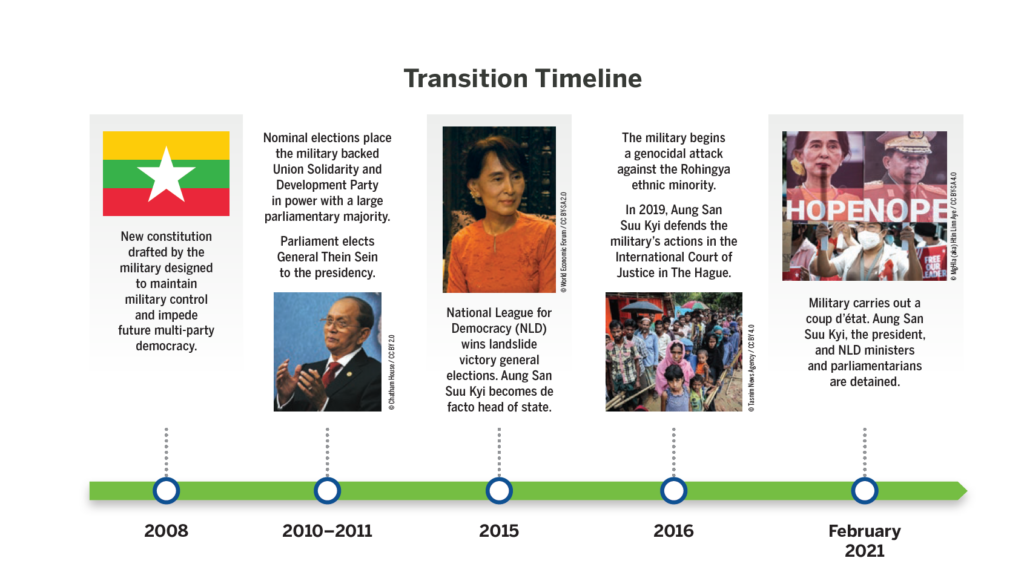

Burma has little experience with democracy. After gaining independence from the British in 1948, the country went through a volatile period of parliamentary democracy marked by ethnic conflict and political strife. In 1962, the military staged a coup and transitioned the country to a totalitarian one-party state. A student uprising in 1988 destabilized the government and thrust Aung San Suu Kyi to the fore as the leader of the country’s pro-democracy movement. The protests led to another coup and the brutal suppression of the student uprising. Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) party was permitted to run in elections organized by the military government in 1990, but after the NLD won in a landslide, the junta, which called itself the State Law and Order Restoration Council, rejected the results and remained in power.

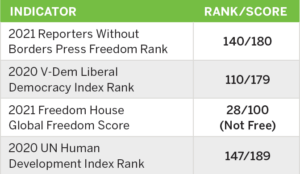

Over the next 20 years, the junta used an extensive apparatus of repression to quell any form of political opposition, and kept Suu Kyi under house arrest or in prison for much of the period. This came at the expense of making Burma an international pariah and the subject of US sanctions. Burma, once one of the wealthiest countries in Southeast Asia, became one of the poorest.

Over the next 20 years, the junta used an extensive apparatus of repression to quell any form of political opposition, and kept Suu Kyi under house arrest or in prison for much of the period. This came at the expense of making Burma an international pariah and the subject of US sanctions. Burma, once one of the wealthiest countries in Southeast Asia, became one of the poorest.

During military rule in the 1990s and early 2000s, media development organizations and donors focused their efforts on supporting media organizations in exile, as there were few independent outlets operating inside the country and it was risky to offer them support. Ethnic minority media and languages were outlawed inside the country, but small ethnic media operated in the borderlands. Many of the exiled news outlets were operated by former students who fled in the aftermath of the 1988 protests, and based themselves in Thailand, India, and Norway. These included the broadcaster Democratic Voice of Burma, as well as the multimedia outlets Mizzima and The Irrawaddy, which became the majority Bamar “mainstream” view into events inside the country.3 The development and professionalization of these organizations would play a major role in shaping Burma’s media environment in the years to come and help propel change during the coming  period of reform, although their influence was not always progressive or beneficial and has at times been a matter of controversy, particularly during the 2017/18 Rohingya crisis.

period of reform, although their influence was not always progressive or beneficial and has at times been a matter of controversy, particularly during the 2017/18 Rohingya crisis.

In 2010, under pressure from the country’s faltering economy and political isolation, the junta held elections for the first time in 20 years. The NLD boycotted the poll and a military-backed party won a heavily scripted vote. Despite doubts that the military’s own party could undertake meaningful reform, the election marked the dawn of a new era. Aung San Suu Kyi was released from house arrest and in early 2011 the new and nominally civilian president, a former general named Thein Sein, announced a series of reforms. These included the release of political prisoners, the negotiation of cease-fires with ethnic armed organizations, and the relaxation of the country’s press restrictions.

That same year, media in the country enjoyed greater freedom when covering the quasi-civilian government’s plans for reform, and by 2012 the change was palpable: Exiled media began returning, imprisoned journalists were released, and legal reforms were initiated, leading to the abolishment of pre-publication censorship. In early 2012, the country’s information minister, Ye Htut, joked that Burmese journalists who still wanted to be censored would have to go to China.4 In 2013, the first independent daily newspapers in half a century were published. New media outlets sprung up across the country, publishing in Burmese and ethnic minority languages, covering issues that had been previously censored. Restrictions on internet access were cut, and access to digital communications surged— especially in cities.

Orders from the Top: Early Reform Efforts

Despite the quick progress, from the start the government presented the reform program as an integral part of the military’s “Seven Step Roadmap to Disciplined Democracy.” This ensured that the reforms were top down and driven by the state under the watchful eye of the military. A small group of international organizations, including UNESCO, Denmark-based International Media Support, and Germany’s Deutsche Welle Akademie, partnered with Burma’s Ministry of Information as part of this effort.

It was this working group that led Burma’s official reform agenda and influenced how other groups participated in, or were excluded from, the reform process.5 Unsurprisingly, the government-led process was viewed by some in civil society as failing to adequately include independent journalists, activists, women, and ethnic minorities.

The government’s approach, influenced by a long-entrenched military mindset, relied on captured or flawed institutions to determine expression regulation and practices.6 For example, a press council was established early in the reform era, ostensibly to promote media freedom and ethics and to mediate public complaints. However, it remained quasi-governmental at best, and was ignored by the military and prosecutors when dealing with critical or sensitive issues.

Donor Decisions

Some donors that began work in Burma in 2012 approached media development primarily as an infrastructure problem. As noted by media scholar Monroe Price, a number of these organizations risked inadvertently reinforcing control by the military by focusing their efforts on supporting government-owned media.7 In hindsight, it is clear that donors dramatically overestimated the commitment of the largely military-controlled state to genuinely reform media.

Focusing development efforts on state media was not the only misstep by donors during this period. Many were eager to see the exiled media outlets and civil society institutions they had helped fund return home and begin influencing Burma from the inside. In some cases, exiled media say they were pressured to move back inside the country and officially register. In hindsight, it is apparent that many underestimated the risks.

“Western donors hollowed out cross-border assistance a decade ago, privileging Yangon-based groups and insisting on formal registration with the government in their zeal to ingratiate the government of then-president Thein Sein,” wrote David Mathieson, a longtime Burma analyst, in a March 2021 article for the Asia Times. “This included many media groups that had operated in exile and are now being targeted for their independent reporting by the [military].”

Although the government attempted to dictate the process—and some donors and media assistance actors helped buttress the government’s efforts to do so—the Burmese media climate was also shaped by activists, civil society groups, and independent journalists acting outside the official reform arena. These latter efforts were influenced by the underground capacity-building work and creative resistance of those who had worked from exile or ethnic border regions in the 1990s and early 2000s.

The work of these groups had a significant impact. In 2012, journalists formed a press freedom committee and organized a march in the commercial capital Yangon, donning black shirts that read “Stop Killing Press.” Many of those who participated were threatened with prosecution. In 2013, three journalist groups organized a public awareness campaign about a proposed media law that would substantially restrict the press. In 2014 and 2016, large groups of civil society organizations gathered to advocate on issues such as the right to information and to overturn provisions of a draconian telecommunications law.

Generational Divide

As Burma’s reform window advanced, it became clear that informal media coalitions were also influencing the country’s changes. The informal effort included two distinct groups that used different approaches to push reform. These two coalitions addressed different matters: the first, the right to information (RTI), the second, digital rights.

The leaders of the first coalition were largely people of significant experience and stature, and primarily consisted of donor-funded nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) that collaborated with quasi-state bodies, including the Myanmar Press Council and the Myanmar National Human Rights Commission. In early 2016, 36 NGOS from across the country established a “Right to Know” working group to raise awareness about the law and the role of civil society in its development.

The coalition undertook a multifaceted strategy to educate grassroots community organizations about the importance of RTI in their lives, while simultaneously trying to get buy-in from government officials by framing RTI as a tool for efficiency and government transparency. The coalition cultivated a select cadre of “champions” to advocate for the passage of an RTI bill in parliament. Ultimately, the draft law was submitted to parliament, but a key provision was deleted and the proposal has since languished with the Ministry of Information. The coup effectively ended efforts to revive it.

The second coalition consisted of a diverse network of largely younger digital rights activists. Many came from grassroots organizations working in areas ranging from free expression to communications technology development and had roots in Burma’s blogging community, which flourished during anti-government protests in 2008.

One rallying point for this second coalition was for the repeal of a section of the country’s telecommunications law, which gave the government broad powers to criminally prosecute peaceful speech for political reasons. A second provision the coalition sought to have removed from the law gave the government broad powers to shut down the internet, as it did repeatedly during the Rohingya crisis in 2017.

The coalition’s proposed changes to the telecom law were met with resistance by Aung San Suu Kyi’s NLD, which had won a majority in parliament in the 2015 elections. Despite the NLD’s promise to change undemocratic laws prior to the election, those involved in the campaign say the party did little to improve laws related to either online freedom of expression or privacy protection.

Still, other efforts were met with more tangible success. A group of technology and freedom of expression organizations from this coalition went on to co-found the Myanmar Digital Rights Forum with support from the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency. In the years before the coup, the group’s annual meeting attracted more than 400 participants from a range of backgrounds and helped raise awareness about digital rights. In 2018, a group of six civil society groups drew global news coverage for their letter to Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg criticizing the company’s response to the spread of anti-Rohingya and anti-Muslim hate speech on its platform during the period of government-backed attacks on Burma’s Rohingya minority.

The letter spurred a response from Zuckerberg and led Facebook to take further action against inflammatory speech on social media. In 2020, Facebook sent a large delegation to the Myanmar Digital Rights Forum, and in the wake of the coup the company has banned military accounts. Following a $150 billion lawsuit against Facebook by a group of Rohingya refugees who alleged the company failed to take action on anti-Rohingya hate speech, the company also started banning the accounts of military-controlled businesses.

The coup has driven many of the leaders of the digital rights movement into exile or into hiding in Burma’s border regions. Some organizations have gone underground or are reorganizing. And , while the military takeover is a setback to the digital rights movement, the leadership and technical skills developed by members of this coalition are continuing to aid media, free expression, and digital security efforts.

A Path Forward

Examining the complex history of media reform in Burma provides many insights for media development organizations working in the post-coup environment and those working in other transitional countries.

First, when working with regimes that have a long history of anti-democratic practices and human rights violations, donors and media assistance actors should be cautious about becoming overreliant on official, mainstream sources and perspectives. In Burma, this distorted their understanding of the country’s political crisis that led to the coup and the risk of escalation. It also prevented them from developing contingency plans to aid local partners and organize a response. In the future, media development organizations must consult widely with local advocates, including ethnic minority media and other marginalized groups during project planning, as their voices provide an alternative narrative of events in the country.

Further, the case study of Burma highlights how locally driven initiatives are more resilient than top-down donor-driven programs. Some of the exile- and ethnic-based media outlets and media support groups nurtured prior to the 2010 opening proved durable drivers of reform efforts. International aid organizations may err by imposing formulaic approaches that are not country specific, and in the case of Burma, the mainstream approach of supporting state media arguably reinforced control by the military. Fostering sustained change requires developing local media reform leadership and stimulating change from the inside, rather than imposing formulas conceived externally.

Burma also highlights the importance of cross-border media in countries with a history of particularly challenging media environments. The robust network of Burmese media organizations, civil society groups, and journalism training initiatives in Thailand, India, and Norway established in the 1990s and early 2000s greatly aided reform efforts during Burma’s opening. Even after the 2021 coup, the experience has helped the next generation of media practitioners establish themselves in exile.

As a corollary to this, it is essential that media development donors provide assistance to freelance journalists operating within the country. In Burma’s current environment, poorly paid freelancers and citizen journalists are vital to providing news and footage to Burmese media. These individuals operate at great risk to themselves, and while there is an assumption that funding provided to media outlets reaches freelance journalists, this is often not the case.

Finally, donors should look to seize on new opportunities created by political reversals. In Burma’s case, there has been an explosion of creative expression and talent in reaction to the coup. Media reform efforts in Burma have historically favored the ethnic majority Bamar, men, and individuals with close ties to international groups. Including a new generation of diverse voices would greatly enrich the media development sector—and prepare it for Burma’s next reform window.

Header Photo Credit: MgHla (aka) Htin Linn Aye / CC BY-SA 4.0

To read the working paper for this case study, as well as the synthesis report and the other country case studies, please see the project landing page here.

Footnotes

- “Support to Myanmar Radio and Television (IMS),” ABC International Development, n.d., https://www.abc.net.au/abc-international-development/projects/myanmar-support-to-myanmar-radio-and-television/; see also “Signing of Grant Agreement on the Project for Extension of Broadcast Equipment of Myanmar Radio and Television,” Japan International Cooperation Agency, March 29, 2017, https://www.jica.go.jp/myanmar/english/office/topics/press170329.html.

- Nan Paw Gay, Director, Karen Information Center; Policy committee chair, Burma News International ethnic news network, in an interview with the author, May 14, 2021.

- Lisa Brooten, “Burmese Media in Transition,” International Journal of Communication 10 (2016): 185, https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/viewFile/3358/1533.

- Union Solidarity and Development Party Information Minister Ye Htut speaking at the first Myanmar Media Development Conference, Chatrium Hotel, Yangon, March 2012.

- Gayathry Venkiteswaran, Yin Yadanar Thein, and Myint Kyaw, “Legal Changes for Media and Expression: New Reforms, Old Controls,” Myanmar Media in Transition: Legacies, Challenges and Change (Singapore: The Institute of South East Asian Studies (ISEAS) Yusof Ishak Institute, 2019), 60.

- Ibid.

- Monroe E. Price, Free Expression, Globalism, and the New Strategic Communication (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 216-218, as cited in Jane McElhone and Lisa Brooten, “Whispered Support: Two Decades of International Aid for Independent Journalism and Free Expression,” in Myanmar Media in Transition: Legacies, Challenges and Change (Singapore: ISEAS Yusof Ishak Institute, 2019), 102.