Key Findings

The 2018 general election represented one of the first times digital disinformation occurred on a massive scale in Pakistan. This report examines different forms of disinformation that circulated online in the lead up to the 2018 elections and its impact on the country’s political discourse, and considers methods to counter disinformation in Pakistan and elsewhere. Ultimately, combating this growing problem will require a variety of stakeholders to work toward a multi-pronged, collaborative response.

● Around 65 percent of Pakistanis aged 16-34 consume news through the internet.

● The rapid spread of disinformation online enables an arsenal of falsities, then used by individuals or groups to target a political candidate

● Setting the record straight once disinformation begins circulating online is incredibly hard to do.

Introduction

On March 2018, the online website Eurasia Future published an article alleging that Pakistan’s former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif hired the political consulting and data mining firm Cambridge Analytica to help him win the 2018 general elections. Coming on the heels of revelations that Cambridge Analytica had used Facebook user data in an attempt to help its clients influence the outcome of the 2016 presidential election in the United States, the story went viral on social media.

Fact-checkers quickly debunked the allegations and clarified that Sharif had not hired Cambridge Analytica. As a result, Eurasia Future took the story down and issued an apology.

Yet, long after the story was debunked, it refuses to die. As one example, in a discussion on prime-time political talk show months after, political analyst Saad Rasool referenced the allegation as if it were true. Neither the anchor nor the other guests on the show corrected him. Rasool shared a clip of his appearance on the show on his Twitter account. Although journalists challenged him and noted that this story was false, Rasool did not take the tweet down.

Pakistan’s brush with the Cambridge Analytica scandal is an example of disinformation— “information that is false and deliberately created to harm a person, social group, organization, or country.” The case offers a cautionary tale of how difficult it is to counter disinformation once it starts to spread.

This report examines the different forms of disinformation that circulated online in the lead up to the 2018 elections, its influence on the country’s political discourse, and considers best ways to counter disinformation in Pakistan.

The Digital Landscape in Pakistan

Around 65 percent of Pakistanis aged 16-34 consume news through the internet. This number is expected to rise in the coming years as internet access becomes more widespread. One of the impacts of this shift to digital platforms is that disinformation can circulate unchecked and at unprecedented speeds, particularly through social media. Indeed, malicious political actors are now employing such technology to orchestrate wider disinformation campaigns and tarnish the reputations of their opponents in order to influence public opinion, particularly around elections.

The challenge that Pakistan faces is not unique. In countries like India, Sri Lanka, the Philippines, and Burma, where there are longstanding ethnic and religious tensions, citizens are coming online in significant numbers and increasingly accessing news on their mobile phones. In places where peace and stability are precarious, the spread of disinformation can have destructive impacts.

National Security-Related Disinformation Campaigns in Pakistan

In recent years, there have been numerous high-profile instances of online disinformation campaigns in Pakistan, often targeting those perceived as too critical of the national security establishment.

In January 2017, four bloggers went missing for three weeks only to return home under unexplained circumstances. Given that the bloggers were quite critical of Pakistani security policies, some accused the military establishment of detaining them. During their alleged detention, an online smear campaign claimed that the bloggers had committed blasphemy, which is punished by death in Pakistan and the mere accusation of which can threaten an individual’s life. As soon as the bloggers got out of detention, they fled the country. The government investigated their supposedly blasphemous statements but found no evidence to charge the men. The apparent aim of the online campaign was to tarnish the bloggers’ reputation and confuse the public about the reasons of their detention.

In late 2016, a similar smear campaign was launched against defense analyst Ayesha Siddiqa, who had written an article that disputed the official narrative of the Pakistani government about an altercation that year with India, with which Pakistan has fought several wars. The campaign, which included doctored images of Siddiqa, accused her of being a traitor working against Pakistan in collusion with Indian officials.

These two instances of disinformation spread online sent a strong message that anyone who challenged the official national security narrative would be strongly penalized.

Disinformation around the 2018 Pakistani General Elections

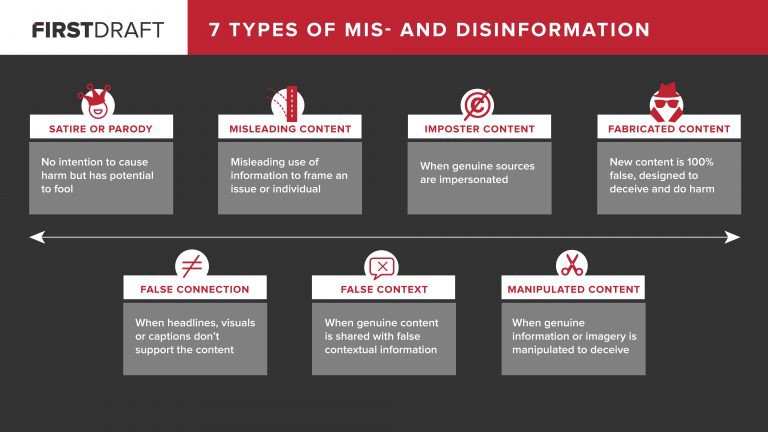

In the run up to, during, and immediately following the 2018 general elections, different types of disinformation were aimed Pakistani citizens. In examining them, this report draws heavily on the analytical framework on disinformation developed by Claire Wardle of First Draft, a nonprofit tracking disinformation globally.

Tactic 1. Misleading and Manipulated Content

The bulk of the campaign disinformation comprised videos and images widely circulated on social media platforms, including Twitter and Facebook, that displayed real events but which intentionally captioned them with the incorrect information.

For instance, when Sharif landed at Lahore airport to present himself for arrest on July 13, 2018, images and videos went viral purported to show thousands of people thronging the roads to the airport in order to welcome the deposed prime minister. The aim, presumably, was to convince the viewer that Sharif remained popular in spite of the corruption allegations against him. AFP fact-checked some of the visuals and discovered that those used were either not of Lahore or were not taken on the day of Sharif’s arrival. In one instance, a video that was viewed 56,000 times was actually from a political protest in London that took place earlier. Nonetheless, the image’s caption read, “Huge Crowd on Mall Road Lahore to welcome Supreme Leader Nawaz Sharif.” In another incident identified by AFP, a video began circulating on Facebook on the day of the election titled “Rigging by Woman Caught on Camera in Pakistan General Election 2018.” It quickly gained more than 150,000 views in the span of four days. However, fact-checkers showed that the video was a 2008 case of election rigging in Karachi.

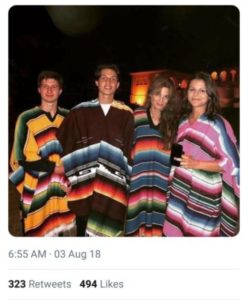

Another case involved a conspiracy theory about Imran Khan. After the elections, an old photo of Imran Khan’s children and his ex-wife vacationing in Mexico wearing ponchos resurfaced on Twitter and was shared with captions that suggested it was taken outside a Jewish prayer site and that the ponchos were traditional Jewish attire. Opponents have long accused Khan of being, as he put it, a “Jewish agent,” and working against Islam and Pakistan, and pointed to the photo as so-called evidence to substantiate their claims.

Screenshot of image that was circulated on Twitter which falsely insinuated that the Khan family visited a Jewish prayer site together.

This tweet is staggeringly ignorant and would be funny if it weren’t dangerous. The photo is taken on a family holiday in Mexico (not Israel) and we are wearing ponchos (not Jewish religious dress) @GhinwaBhutto – shame on you. https://t.co/PenNwbe6Mt

— Jemima Goldsmith (@Jemima_Khan) August 6, 2018

Tactic 2. Misrepresentation of Satire and Parody

The circulation of content developed as satire as if it were factual news was another means to spread disinformation. In one case, the satire magazine, the Dependent published an article titled “Imran Khan is the best ex-husband I’ve ever had,” ostensibly written by his former wife Reham Khan, a vocal critic of her ex-husband. Although the magazine claims that it clearly provided a disclaimer in the header and footer of the print version, these were often cropped out when shared online, making it difficult for readers to quickly identify it as satire. The Dependent thus used this article, which went viral, to prop up public opinion of Khan during the campaign.

We will be taking you to court for this piece.

This is not satire.

It is deliberate misinformation & blatantly sexist. pic.twitter.com/j5axjEx7Sh— Reham Khan (@RehamKhan1) July 30, 2018

In response to this incident, the Depend now inserts a disclaimer into the article itself and is considering avoiding the use of original photos, which contributed to the article’s reception as legitimate news.1

Tactic 3. Fabricated Content

During the election period, falsely attributing statements to leaders and public officials became a popular disinformation tactic in Pakistan. Doctored images of political leaders along with fabricated statements, often incendiary in nature, were widely circulated on social media to malign the reputations, provoke feelings of hatred from specific communities, induce panic in the public, and pit political opponents against each other. In the Pakistani context, misattributing commentary on sensitive religious and ethnic matters may pose a threat to the lives of wrongly accused individuals.

In a case immediately following the election in which Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) came to power, Twitter posts accused Federal Minister for Human Rights Shireen Mazari of hateful comments about the Pashtun ethnic group, which is concentrated in areas bordering Afghanistan. According to an image circulated on the social media platform, Mazari said: “There is no difference between Pashtuns and Taliban. Pashtuns are (by nature) extremists.” Such a disparaging statement against one of the largest ethnic groups in Pakistan risked inflaming pre-existing tensions, and Mazari immediately took to her Twitter account to set the record straight and defend her reputation.

Dr @ShireenMazari1 made no such statement. Its a totally fake/doctored screenshot being circulated on social media and WhatsApp groups. pic.twitter.com/sxffuStGfC

— Ahsan Alavi (@ahsanalavi) August 30, 2018

In a more sophisticated case of content falsification, someone created an image of using the logo of Pakistan’s most widely circulated English-language newspaper, Dawn. According to the falsified screenshot circulating on Twitter, PTI leader Faisal Vawda withdrew a corruption petition against a long-time political rival after becoming allies in the new government. Vawda threatened to take legal action against the newspaper before Twitter users pointed out that the Dawn was not responsible for the story.

Tactic 4. Imposter Content

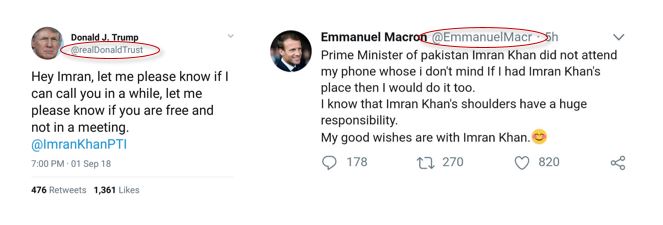

The impersonation of prominent personalities on social media is also a popular way to mislead citizens. Twitter accounts claiming to be US President Donald Trump, French President Emmanuel Macron, Pakistani television star Shabnam, and Kashmiri leader Mirwaiz Umar Farooq, for instance, voiced support for the incumbent Prime Minister Khan immediately following the general elections, with the intent of convincing the public about Khan’s popularity among world leaders.

In one case, the impersonators used the same Twitter account, but kept changing the handle’s name and associated image. Remarkably, the impersonators failed to delete earlier tweets issued under another name, making it incredibly easy to see that the comments were fabricated.

Unfortunately, this remains an effective way of spreading disinformation in Pakistan, where people are not likely to spend time on verification. In some cases, even legacy media were duped. Impersonators online not only confuse people about the thoughts of political leaders but can also pose security threats when such accounts are used to make comments on sensitive matters.

Assessing the Impact of Disinformation on the 2018 Elections

It would be far-fetched to claim that online disinformation influenced the outcome of the 2018 elections in Pakistan. More than 75 percent of the population still does not have access to the internet. Still, the impact of this disinformation does not remain restricted to cyberspace. Rather, it trickles into other media, like print and television, and in the process gets further legitimized, even if this often happens unintentionally. The competition by news outlets to be first in breaking stories has, unfortunately, led to cases where disinformation gets picked up without adequate verification. As reporters increasingly look to social media to cover the day’s news, online disinformation is expected to continue to find its ways into traditional news coverage.

The spread of disinformation creates factoids in an arsenal of falsities that can be used by individuals or groups to target a political candidate. The magnitude of the lie is not always even its most important component. Circulating false information about seemingly trivial details, like the number of cars in a political motorcade, can be used to capture attention and portray a candidate in a less than flattering light.

Research suggests consumers of information are highly biased and prone to believe things that already fit their dominant worldview. If they support a particular ideology, party, or leader, they will look for information that confirms their bias and disregard evidence that contradicts their views. If they dislike something or someone and come across a post that would support their perceptions against that person, they will not trust that piece of information but also share it without verification.2

As a result, disinformation campaigns can increase the polarization in the political landscape. As veteran journalist Zarrar Khuhro noted, the perpetrators of disinformation are acting on the principle that “if you cannot convince them, confuse them.”3 It is a tool at the hands of different political stakeholders to confuse the public about the truth by flooding social media with made- up stories. Amid all of the false stories circulating online, it can be hard to sort fact from fiction.

Disinformation might not have directly influenced the outcome of the elections, but it did encourage animosity among political rivals online and exacerbate polarization. Further, given that digital literacy remains quite low in Pakistan, audiences are extremely vulnerable to accepting false information as fact.

The Perpetrators of Disinformation

Perpetrators of disinformation in Pakistan come from different political backgrounds, and no one political force is to blame.

Major political parties, including the ruling PTI and the opposition Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz (PML-N) bear a great deal of the blame, according to the experts interviewed for this report. Additionally, the digital editor of the local English newspaper Daily Times Farhan Janjua noted that religious and sectarian groups also spread disinformation against their opponents.

Many experts also believe that perpetrators of political disinformation include groups affiliated with the powerful military establishment. Through false identities online, these groups are believed to have an active presence on social media and manipulate political conversations, stir religious discord, and spread disinformation against opponents. These concerns were substantiated by Facebook’s decision in April 2019 to remove 103 pages, groups, and accounts linked to the Inter-Services Public Relations (ISPR), the military’s public relations arm for engaging in “inauthentic behavior” that violated Facebook’s terms of service.

Of course, it cannot be said with certainty if cyber trolls are officially tasked by top political or military leadership to engage in such behavior. As Sadaf Khan, cofounder of Media Matters for Democracy Pakistan, puts it, “I don’t think that there is one person or one department within political parties focusing primarily on false news. . . . if there is an official directive at the management level, it would be pretty generic. But how people deconstruct it and what kind of misinformation they want to spread is happening at [a] much lower level because I don’t see much intellectual involvement in the false news.”

Efforts to Counter Disinformation in Pakistan

It takes far more time to counter false news than to spread it. Unlike in many developed countries, where extensive resources are being dedicated to debunk disinformation, efforts to counter disinformation are nascent in Pakistan. Some Pakistani policymakers are calling for increased legislation. Already on the books is Section 20 of the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act of 2016, which criminalizes defamation against an individual. Those found guilty can face up to three years imprisonment or a fine of up to 1 million Pakistani rupees ($6,367). However, thus far, it has primarily been used to prosecute journalists who are accused of defaming the military and sometimes the judiciary.

Prior to Pakistan’s 2018 elections, Facebook, in the limelight for its platform’s misuse during the 2016 elections, led efforts in countering disinformation in Pakistan. The company launched a joint initiative with AFP and collaborated with local civil society organizations to identify and contextualize likely instances of disinformation. Facebook also spearheaded an online media literacy campaign, encouraging audiences to consider specific elements of any news story before accepting it as a fact. Those tips were published as full-page ads in local newspapers.4 Major publications also occasionally published articles debunking disinformation and misinformation online.

Raising awareness of the issue, among both news consumers and local journalists is key to countering disinformation. Facebook’s public campaign on misinformation was a novel initiative, but the extent of its impact is yet to be seen. Khuhro, the journalist at Dawn, recommended that news organizations consider establishing a dedicated fact-checking resource to counter disinformation.5 Sadaf Khan of Media Matters for Democracy argued that a more effective way to counter disinformation would be to invest in improving the quality of journalism overall.6

The Pakistani government has launched its own effort to counter disinformation. In October 2018, the Pakistani Information Ministry set up a Twitter account called “Fake News Buster” to debunk online disinformation. The initiative has been met with mixed response, lauded by some as proactive while others are wary of the government stepping in to debunking fake news and fearing its politicization.

Conclusion

As elsewhere, there is no quick fix solution to countering disinformation in Pakistan. Adding to the challenge in Pakistan is the fact that all of the relevant stakeholders appear to be working within their own silos. Government responses seem to suggest that it’s Twitter-based Fake News Buster and a new criminal law will resolve the issue. Facebook and other social media platforms prefer self-regulation, although they are struggling to determine how aggressive to be in moderating content. Some journalists advocate fact-checking efforts as the best approach to countering disinformation, while others argue that population-wide media and digital literacy programs are what is needed most. In short, there is no consensus about what needs to be done. Moreover, each stakeholder is skeptical of the others’ role and questions each other’s commitment to countering disinformation.

As elsewhere, there is no quick fix solution to countering disinformation in Pakistan. Adding to the challenge in Pakistan is the fact that all of the relevant stakeholders appear to be working within their own silos. Government responses seem to suggest that it’s Twitter-based Fake News Buster and a new criminal law will resolve the issue. Facebook and other social media platforms prefer self-regulation, although they are struggling to determine how aggressive to be in moderating content. Some journalists advocate fact-checking efforts as the best approach to countering disinformation, while others argue that population-wide media and digital literacy programs are what is needed most. In short, there is no consensus about what needs to be done. Moreover, each stakeholder is skeptical of the others’ role and questions each other’s commitment to countering disinformation.

For true progress to be made on countering disinformation, all stakeholders in Pakistan need to work together toward a deeper understanding of the problem and come up with a multi-pronged, collaborative response. Components of such an initiative could include social media public awareness campaigns, workshops for journalists and social media influencers, and recommendations for school and college curriculums. Additionally, sponsoring independent research to assess the impact of disinformation and study the efficacy of proposed solutions would save time and resources and ensure widespread public ownership in the collective efforts to address disinformation.

Disincentivizing the production of disinformation in the first place and identifying ways to diminish its distribution once created will be key to addressing the problem. First, greater pressure on the actors who deliberately create and disseminate misleading content can help stop disinformation in the first place. Second, social media companies must become more responsible for monitoring content that appears on their platforms. Currently, salacious content drives social media engagement and thus is profitable to social media companies, which make money through advertising. Successful disinformation efforts need to upend this perverse incentive structure that can inflict real social harm by ensuring that algorithms of social media platforms do not amplify the spread of salacious content.

In countries like Pakistan, the internet has the potential to be a driver of development and progress. However, this will only happen when citizens have confidence that the information they find online is factual and trustworthy. Otherwise, the decisions individuals make, including voting, will be skewed. Disinformation distorts the public sphere, aggravates social fractures, and undermines the legitimacy of elections. Although journalists and news organizations have an important role to play in combating disinformation, they cannot solve the problem alone. Meaningful solutions will require a broader effort by all sectors of society. Unchecked, the poisonous effects of disinformation will only be more potent in future Pakistani elections.

Footnotes

- Kunwar Khuldune Shahid (correspondent for the Diplomat), interview with the author, September 30, 2018.

- Zarar Khuhro (veteran journalist), personal communication with the author, September 18, 2018; Sadaf Khan (cofounder and director of Media Matters for Democracy), personal communication with the author, September

- Zarar Khuhro, personal communication with the author, September 18, 2018.

- Sarim Aziz (Facebook Public Policy Manager), email communication, September 26, 2018.

- Zarar Khuhro, personal communication, September 18, 2018.

- Sadaf Khan, personal communication, September 20, 2018.