Key Findings

As policymakers around the world consider how to rebalance the relationship between Big Tech and the news industry, it is imperative that they take a global view and consider the implications for independent news outlets in developing and low-income countries. Pioneering laws and policies like Australia’s 2021 News Media Bargaining Code and the European Union’s 2021 Digital Copyright Directive, which compel platforms to pay for the news they use, have inspired publishers globally and spurred other countries to pursue similar policies. This report examines three types of policy interventions: taxing digital advertising, empowering news media to collectively bargain with Big Tech, and requiring tech platforms to pay licensing fees for using news content. It finds that implementing any of these approaches is not just about political will, but also about institutional design, legitimacy, and trust.

– Facebook and Google have a duopoly on the digital ad market, leaving news outlets struggling to generate revenue from online content.

– To effectively design policies monetizing digital news content, more research is needed on the link between referral traffic and news site revenues.

– Successfully implementing similar policies in developing economies requires strong institutions and professional associations that can represent media outlets, facilitate bargaining, and independently manage and monitor distribution of revenues.

Introduction

As more people get their news online, journalism has become more dispersed and untethered from the institutions that produce it, the advertisers that fund it, and the public that needs it. Meanwhile, as tech companies have gotten bigger, wealthier, and more integrated into every aspect of daily life, journalism has struggled to adapt to shrinking newsrooms and budgets, leading many to wonder if Big Tech should subsidize the news they use.

The tenuous sustainability of news media outlets, especially in developing economies and emerging democracies, is not new. But the COVID-19 pandemic and democratic backsliding worldwide have made governments acutely aware of the vital need for local, fact-based journalism1 and energized a global conversation about how public policy can be used to support independent media.2 Widespread recognition that news media are operating on an uneven playing field has prompted countries around the world to consider redistributing some of the tech industry’s profits to the news industry.

Over the past year, journalists and publishers globally have been inspired by bold new initiatives in developed economies to compel platforms to pay for the news they use. With the impetus provided by Australia’s 2021 News Media Bargaining Code and the European Union’s (EU’s) 2021 Digital Copyright Directive, there is an opportunity to learn from these approaches and consider how they can be used to support independent media, particularly in developing countries and emerging democracies. These two laws have been pioneering in their efforts to force Big Tech to pay for news, and have created an opening for other countries to do the same. Press groups in Brazil, India, Indonesia, and southern Africa have launched campaigns to implement similar frameworks in their own countries.

Over the past year, journalists and publishers globally have been inspired by bold new initiatives in developed economies to compel platforms to pay for the news they use. With the impetus provided by Australia’s 2021 News Media Bargaining Code and the European Union’s (EU’s) 2021 Digital Copyright Directive, there is an opportunity to learn from these approaches and consider how they can be used to support independent media, particularly in developing countries and emerging democracies. These two laws have been pioneering in their efforts to force Big Tech to pay for news, and have created an opening for other countries to do the same. Press groups in Brazil, India, Indonesia, and southern Africa have launched campaigns to implement similar frameworks in their own countries.

The debate over what role tech companies should play in addressing imbalances in news marketplaces is wide-ranging but tends to focus on developed Western countries with large economies and regulatory expertise. These discussions seldom consider the constrained choices media face in countries around the world that are still struggling to transition to the digital age, particularly in developing countries.3 “They [media in developing countries] have not really even had a chance to develop online businesses because Facebook came in and took it all before they even got a chance to get there,” said Prue Clarke, executive director of the media development organization New Narratives.4 Clarke works with media in Liberia, where internet penetration remains stubbornly low and commercially viable independent news media are rare.

Currently, regulators and media globally are exploring how to renegotiate the relationship between tech platforms and the news industry given their roles in the information ecosystem and their inverse financial trajectories.5 In these media-focused discussions the term Big Tech typically refers to Alphabet (which owns YouTube and dominates search) and Meta (which owns Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp), though the term is used as shorthand to also refer to other Silicon Valley companies that dominate the digital public sphere such as Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, and Twitter.

Efforts to rebalance the relationships between journalism and Big Tech are focused primarily within three distinct, yet at times overlapping, policy areas: digital taxation, competition policy (also referred to as antitrust), and intellectual property. In all three cases the goal is to generate revenue or subsidies for news outlets to help sustain independent journalism. This report analyzes the evidence and justification for these various policies and examines the implications for news media in low-income and developing countries. It identifies the particular challenges that countries with small markets, weak currencies, less stability, and less press freedom face in pursuing the policies outlined in this report, underscoring the importance of a coordinated global approach.

Journalism's AdTech Problem

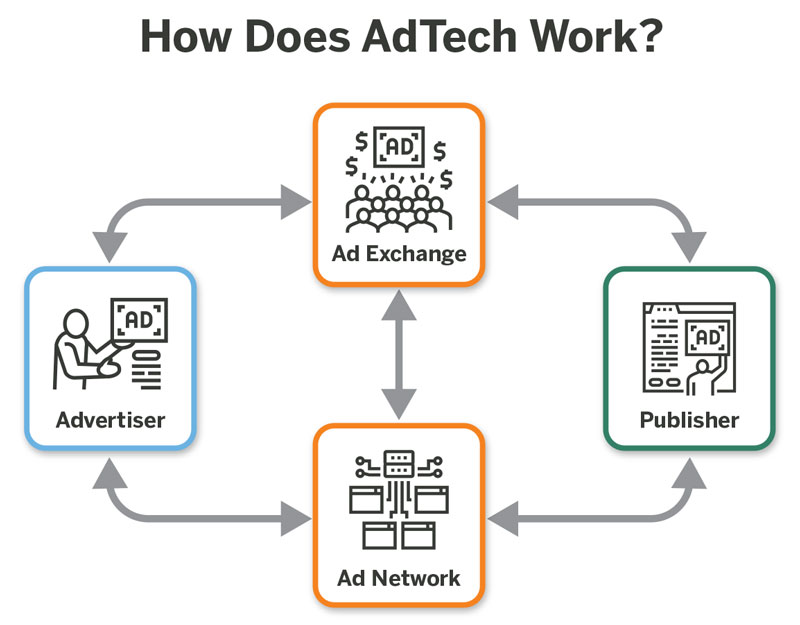

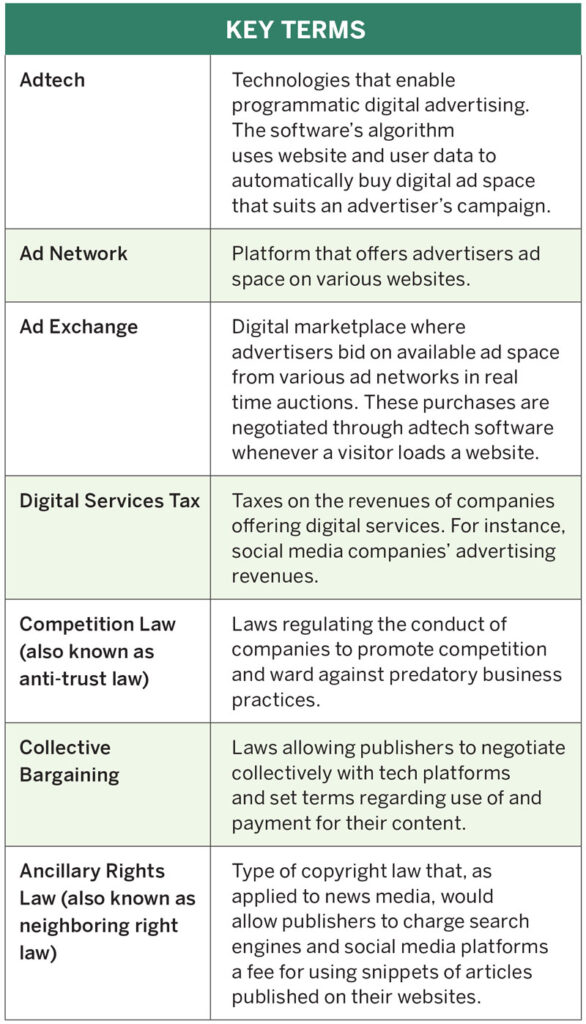

The decline of advertising revenue, the rise of “AdTech,” and the tenuous sustainability of most independent news organizations have led to a decoupling of advertising and journalism that threatens the very foundation of a commercial news model. AdTech refers to the automated technologies and methods of buying and placing digital ads that enable programmatic advertising and microtargeting by advertisers and agencies that create, run, manage, and measure online advertising campaigns.6 Currently, the global digital advertising and publishing ecosystem is dominated by Google and Meta, which capture more than 60 percent of digital advertising revenue.7 These two companies now sit between publishers and advertisers, and have created a complex and opaque digital advertising system.8 Advertising revenue that once went directly to publishers and was used to support journalism now flows to the coffers of Big Tech.

The decline of advertising revenue, the rise of “AdTech,” and the tenuous sustainability of most independent news organizations have led to a decoupling of advertising and journalism that threatens the very foundation of a commercial news model. AdTech refers to the automated technologies and methods of buying and placing digital ads that enable programmatic advertising and microtargeting by advertisers and agencies that create, run, manage, and measure online advertising campaigns.6 Currently, the global digital advertising and publishing ecosystem is dominated by Google and Meta, which capture more than 60 percent of digital advertising revenue.7 These two companies now sit between publishers and advertisers, and have created a complex and opaque digital advertising system.8 Advertising revenue that once went directly to publishers and was used to support journalism now flows to the coffers of Big Tech.

In individual countries, the dominance of Google and Meta may be even greater. For example, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission found that Google and Facebook (now Meta) accounted for more than 80 percent of the country’s digital advertising market.9 In India, experts estimate that small publishers give upwards of 25 percent of ad revenue to Alphabet alone, though it’s hard to know since the platform is not required to share revenue or data with publishers.10

“Since Google is the majority stakeholder in the digital advertising space, they unilaterally decide the amount to be paid to the publishers for the content created by them [and] also the terms on which the amount has to be paid. The publisher does not even get paid for the snippets Google uses from their platform,” said Sujata Gupta, secretary general of the Digital News Publishers Association.11 Similarly, when advertising generates a quarter of a media organization’s revenue, which is the case for independent digital media in Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia,12 diverting already limited advertising revenue compounds media sustainability challenges.

The complexity of the AdTech system also makes it exceedingly difficult for publishers to successfully navigate. It is so complex that it often requires publishers to hire dedicated technical teams to negotiate the system in order to take advantage of the programmatic advertising that does exist.13 This is why many outlets in developing countries use Google AdSense, which is less complex than other advertising exchanges, though also a less lucrative advertising option for publishers.14

According to Wesley Gibbings, general secretary of the Association of Caribbean MediaWorkers, the revenue problem the new AdTech system has caused for publishers is especially acute “where you already have thin journalistic resources, and the material is basically just stolen and redistributed without any acknowledgement, without any kind of benefit to the creators.”15 Any change in the system that makes it harder for news outlets to pay the bills is going to be more deeply felt in places where news media are already under severe financial stress.

In addition to the dominance of the duopoly, a labyrinth of data management platforms and exchanges means that publishers receive a significantly reduced portion of the money spent by advertisers. The lack of data and traceability in the AdTech system makes it difficult to know where the money goes, though a handful of efforts suggest that greater competition as well as transparency could help remedy this challenge. A benchmark study found that United Kingdom (UK) publishers received an average of just 51 percent of advertiser spend, with the remainder going to various intermediaries in the supply chain, with a third of this unaccounted for.16 The UK’s regulator estimated that, on average, at least 35 percent of the value of advertising went to intermediaries rather than publishers.

In short, the rise of the digital AdTech system has resulted in a new advertising ecosystem that has effectively redirected ad revenue that in the past went directly to publishers.17 Big Tech now dominates the digital advertising market and controls the infrastructure and market for digital advertising. The implications for news outlets around the world have been nothing short of dire as they seek to maintain revenue streams that can support journalism. This is why publishers and policymakers in many countries are now examining novel ways to fund independent journalism in a market that has been transformed by Big Tech.

Rebalancing the Relationship between News Media and Big Tech: Three Policy Options

At present, there are three policy areas put forward as mechanisms to rebalance the relationship between news producers and Big Tech: digital taxation, competition policy (also referred to as antitrust), and intellectual property. Understanding the policy proposals is crucial to being able to evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of pursuing them in different country contexts.

Taxing Digital Advertising to Support Journalism

Given that the digital advertising system has generated record-breaking profits for companies like Google and Meta and that many people use these platforms to access news content produced by publishers, the idea of taxing digital advertising has been gaining interest in recent years among publishers and policymakers.18 It should be noted that there are also broader proposals to tax digital services gaining steam internationally, but these are not primarily aimed at supporting the news media. For example, Canada, the EU, India, Israel, and South Africa have proposed or adopted revenue-based taxes on digital advertising; however, the news industry is not a beneficiary of these plans.19 For the purposes of the media development sector, however, interest is greatest in the proposals that would channel taxation revenues to journalism.

In 2021, the National Association of Journalists in Brazil launched a campaign calling for taxes on digital platforms and the creation of a National Fund for the Support and Promotion of Journalism (Funajor).20 The proposal would impose a graduated tax of up to 5 percent on large digital platforms based on gross revenue.21 US-based Free Press has proposed that revenue generated from a new 3 percent tax on targeted advertising in the United States could be used to fund a public interest media system comprising diverse, local, independent, and noncommercial journalism, and news-distribution models that don’t rely on data harvesting.22 There would be a certain threshold imposed so that for-profit journalism outlets would not be affected, and an independent endowment could use grantmaking to distribute funding.

Creating an independent endowment to distribute tax revenues to media presents its own challenges. Few emerging democracies have instructive experience in this area.23 South Africa’s Media Development and Diversity Agency—established by parliament to provide direct funding to community media—has been hampered by operational challenges and low resourcing.24 Some countries also have prohibitions against assigning tax revenue to a specific issue area and would be prevented from using digital taxes to support media. In Chile, for example, there was chatter in the journalism and digital rights communities about adopting such a policy, but it would have required a constitutional amendment to allow tax revenue to be directly funneled to the news.25

Furthermore, a lack of data and independent research into the effects of advertising approaches on traffic and revenue among media in different contexts means there is limited evidence to inform public policy. At this point it is unclear to what extent news content is actually driving advertising revenue. Improving transparency of this notoriously opaque market as well as competitiveness would help level the playing field and give the media a fighting chance to reclaim a share of the advertising pie. That’s where competition policy and intellectual property regulations come in as well.

Leveling the Playing Field: Increasing News Media Bargaining Power

Even as publishers struggle to make ends meet in the tech-dominated advertising era, they are also faced with the fact that much of their content appears on those same platforms without compensation or permission. On the one hand, the headlines, photos, and snippets that show up in search results, social media feeds, and news aggregators may drive some traffic to publisher websites and potentially generate revenue. This is considered referral traffic, as opposed to direct or organic traffic. On the other hand, news improves the quality of content on tech platforms whose aim is to keep users in their walled gardens for as long as possible. Making platforms pay for the news they use could become a more attractive option than taxing digital advertising by forcing the companies to negotiate directly with publishers rather than putting the government in the middle.

Australia made headlines in 2021 when it passed legislation requiring Facebook and Google to share algorithmic information with and pay licensing fees to news organizations. The News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code26 was enacted after a landmark report by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC). The report highlighted that Big Tech platforms were benefiting from news content27 without paying for it while controlling much of the advertising market that the news industry relies on.28 The ACCC based its decision in part on the intrinsic value news provides to the platforms.29

Australia made headlines in 2021 when it passed legislation requiring Facebook and Google to share algorithmic information with and pay licensing fees to news organizations. The News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code26 was enacted after a landmark report by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC). The report highlighted that Big Tech platforms were benefiting from news content27 without paying for it while controlling much of the advertising market that the news industry relies on.28 The ACCC based its decision in part on the intrinsic value news provides to the platforms.29

Google and Facebook threatened to pull their services from the Australian market to stave off the law,30 a threat that Facebook made good on when it shut down its service for nearly a week in 2021, just as the government was rolling out the COVID-19 vaccine. The shutdown had an outsized effect on small, nonprofit, regional, community, and rural media outlets, cutting them off from audiences that rely on social media for local news.31 “Never has our media been more vital than during a global pandemic,” said Dot West, chair of First Nations Media Australia, underscoring the need to differentiate between commercial and community media. “[We] should not be negatively impacted by an industry-wide response to corporate interests.”32

The platforms and publishers eventually came to a compromise that included secret multimillion dollar deals with the country’s largest publishers while local news outlets got about $20,000 to $40,000 a year.33 Other media outlets, including specialty news and a public service broadcaster, were denied deals and left wondering why they didn’t end up benefitting from the new framework, although they are lobbying the government to redress this inequity. “While deals have been made with media outlets owned by millionaires, true community publishers have been completely overlooked and ignored,” said Graeme Watson, co-owner of OUTinPerth.34

“Facebook has not provided us with clarity as to their rationale for not entering into an arrangement with us. We’ve attempted to elicit a response from Facebook about their rationale. We’re still a little in the dark,” James Taylor, managing director of public broadcaster SBS, told a parliamentary committee.35

The new legislation also recognized the massive financial and editorial impacts that major tweaks to platform algorithms or priorities can have on news organizations, including closures and layoffs.36 For example, when Facebook decided to prioritize video in 2015, publishers pivoted to video, only to find out later that the company had inflated its metrics, according to a lawsuit.37 When it decided in 2018 to de-prioritize professionally produced media content in favor of so-called meaningful content from friends, news organizations suffered.38 Australia mandated that tech platforms tell news publishers about algorithmic changes likely to significantly impact referral traffic or ranking.39

Australia’s bargaining code legislation has inspired news media around the world to consider whether they could pursue a similar strategy in their own countries. For example, a media sustainability task force organized by the Press Council and other media organizations in Indonesia has drafted legislation modeled on Australia’s that would create a mechanism for news media and tech platforms to negotiate licensing fees and provide greater algorithmic transparency.40 In Indonesia, however, they are mindful of how bargaining code laws can privilege big media conglomerates. This perception has dogged the Australian law and helped to scuttle the Brazilian law.41 As such, Indonesia will provide an important test case of whether a bargaining code policy can also benefit smaller, local outlets.

In southern Africa, Alvin Ntibinyane, managing partner of the INK Centre for Investigative Journalism in Botswana, is trying to get support from the media development community to lobby regional policymakers to take a similar approach in the Southern African Development Community region. This approach doesn’t yet have traction and Ntibinyane cites the lack of technical expertise on both technology and tax policy as limiting its efficacy.42 In Latin America, media are taking a “wait and see approach, but also waiting for an opportunity to jump in,” according to Juan Carlos Lara of Derechos Digitales.43

In southern Africa, Alvin Ntibinyane, managing partner of the INK Centre for Investigative Journalism in Botswana, is trying to get support from the media development community to lobby regional policymakers to take a similar approach in the Southern African Development Community region. This approach doesn’t yet have traction and Ntibinyane cites the lack of technical expertise on both technology and tax policy as limiting its efficacy.42 In Latin America, media are taking a “wait and see approach, but also waiting for an opportunity to jump in,” according to Juan Carlos Lara of Derechos Digitales.43

India is one of a handful of countries in the Global South that has both the expertise, user base, and regulatory influence to pursue the Australian strategy. In January 2022, publishers filed a complaint with India’s competition authority claiming that Google unfairly dominates the news aggregator business and does not allow publishers to competitively earn revenue on ads due to a “lack of transparency and information asymmetry.”44 The investigation into whether Google’s use of snippets is a result of imbalanced bargaining power hinges on whether the referral traffic to news publisher websites is affected, and then whether this impacts publishers’ ability to make money. But the Digital News Publishers Association, which filed the suit, has been reticent to discuss the complaint and it has gotten little media coverage.45

Rethinking Intellectual Property Rights: Copyright and Licensing for Publishers

Lawmakers have also turned to intellectual property rights as they try to give publishers a leg up in the digital age. Search engines, timelines, and news aggregators are filled with news snippets and images that are culled from publishers and authors without permission or payment. The “fair use” exception in copyright law typically permits the use of small amounts of copyrighted material under certain conditions without prior permission of the copyright holder, but the question of whether this applies to online platforms, particularly when they are for-profit, remains unsettled. Currently, search engines and social media sites use headlines and short descriptions of websites, including news articles, on their platforms, but many publishers argue that this use allows Big Tech to profit from news content produced by others without having to pay for it.

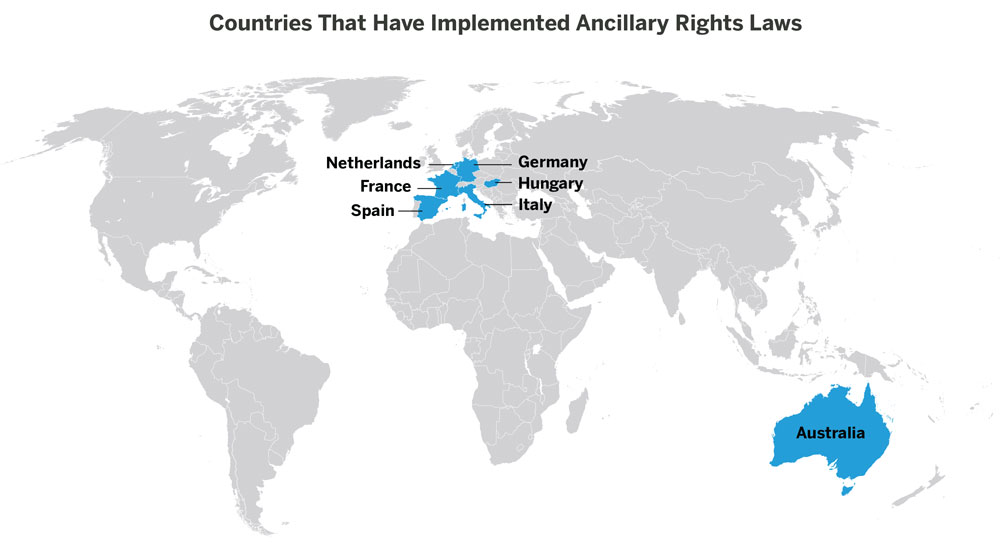

In Europe, regulators have tried to renegotiate power dynamics to allow news outlets to be remunerated when online service providers use their content—even just headlines and news snippets—by applying the concept of “ancillary copyright” to news content. In practice, the adoption of ancillary copyright, sometimes referred to as “neighboring rights,” for news content could mean that some platforms and aggregators would need to pay publishers a fee anytime they posted a news headline or snippet.

The 2021 EU Digital Copyright Directive created a right for press publishers, not just authors, to claim copyright.46 This approach emerged from experiments in Germany, Spain, and other European countries over the past decade, with mixed results. It creates a framework for negotiating licensing fees and distributing those back to publishers. Requiring each entity to negotiate and collect rights and payments is not feasible, so collective management organizations are needed to implement this type of approach. This requires digital rights management systems and collecting agencies to negotiate, monitor, collect, and distribute the licensing fees to copyright holders without requiring advance permission.47 It also requires a significant degree of trust in addition to technical expertise.

Not everyone in the journalism sector is on board with this strategy. Some worry about the lack of transparency in commercial deals negotiated between publishers and platforms and that small outlets will get left out of deals negotiated between large publishing conglomerates and Big Tech. There is also a concern that journalists will not actually benefit from this arrangement and will be left behind. Other observers warn that imposing a “link tax” would undermine the free flow of information online. The directive could provide a global template like those established by other major European digital legislation.48

In 2013, after extensive lobbying by Axel Springer, Germany’s largest publishing group, and other major German news outlets, Germany’s Copyright Act was amended to include an “ancillary right” that gives press publishers the exclusive right to commercially exploit their content for one year unless a third party obtained a license.49 Publishers then sued Google for failing to negotiate payments for use of news snippets. In response, Google stopped using snippets unless a publisher opted in to the Google News aggregator. A number of German publishers opted in to the Google News aggregator without charging Google a licensing fee. However, Axel Springer refused to sign a free licensing deal and saw a 40 percent drop in traffic from search results and an 80 percent drop from Google News referrals.50 After just two weeks, Axel Springer gave in and joined the other German news organizations in licensing its content for free rather than giving up referral traffic.51

The following year, Spain adopted a new copyright law that similarly required news aggregators like Google to pay publishers for including snippets and headlines, but also tried to make sure that publishers wouldn’t be compelled to let platforms use their content for free. Unlike in Germany, publishers were required to receive compensation and were prohibited from refusing the use of “non-significant fragments” of their articles.52 By making compensation compulsory it foreclosed the option to opt out53 but ended up splitting the publishing community.54 The largest Spanish newspaper association and several digital-only publishers initially supported the law, but ultimately joined forces with Google and the main local news aggregator, Menéame, to lobby against it.

Before the law came into effect in 2014, Google News decided to shut down in Spain. Although a handful of empirical studies showed a general decline in traffic, the timeframes, types of traffic, and impact on different-size publishers varied,55 and a longer-term study by Spanish publishers and a news industry group found that this reduction in traffic was low and temporary and offset by increased higher-quality organic traffic.56

The Spanish law seemed to be a failed experiment in revenue generation until 2017, when Spain’s professional association for authors and publishers, CEDRO, proposed a rate of five cents per active user per day.57 Upday, a news aggregator that comes pre-installed on most Samsung phones in many European countries, agreed to pay the licensing fees.58 Owned by Axel Springer, Upday became the first, and only, publishing group to ink a deal with a news aggregator and in doing so it legitimized CEDRO’s proposed rate and set a precedent for future agreements.59 But in 2020, CEDRO unsuccessfully sued Google claiming that its Discover mobile service amounted to an aggregator and was therefore owed millions in unpaid licensing fees; it was instead forced to pay the tech behemoth’s legal costs.60

The Spanish law seemed to be a failed experiment in revenue generation until 2017, when Spain’s professional association for authors and publishers, CEDRO, proposed a rate of five cents per active user per day.57 Upday, a news aggregator that comes pre-installed on most Samsung phones in many European countries, agreed to pay the licensing fees.58 Owned by Axel Springer, Upday became the first, and only, publishing group to ink a deal with a news aggregator and in doing so it legitimized CEDRO’s proposed rate and set a precedent for future agreements.59 But in 2020, CEDRO unsuccessfully sued Google claiming that its Discover mobile service amounted to an aggregator and was therefore owed millions in unpaid licensing fees; it was instead forced to pay the tech behemoth’s legal costs.60

Google News only reopened in Spain on June 22, 2022, after the country dropped the mandatory collective licensing fee and implemented the EU’s copyright directive. The new legislation still requires Google to negotiate with directly with publishers, but it simply allows for licensing fees without requiring them.61 While the deal with Upday demonstrated a glimmer of hope, Spain’s experiment with mandated licensing fees ended before it could gain much traction. Any country seeking to implement similar measures will need to be prepared to meet steep resistance from tech giants.

The Link between Traffic and Revenue

A key assumption underpinning changes to existing intellectual property and competition law is the idea that platforms derive a benefit from news content and that publishers are not adequately compensated for use of their content. Search and social media are the main ways that people come across news if they don’t go directly to the outlet’s webpage, and relatively few people use news aggregators.62 Direct traffic to a news website lets publishers collect revenue and data directly from their news consumers while improving brand recognition and potentially turning visitors into subscribers.

The German and Spanish cases demonstrate that the link between referral traffic and revenue is not quite so clear cut. Making aggregators pay to feature publishers’ content may create a new source of revenue, but it could also lead to less direct traffic to news sites and thus less brand recognition for publishers. This loss of visibility would be particularly problematic for smaller, less established news outlets. Even in cases where outlets receive more traffic from aggregators, visitors are more likely to be directed to individual article pages than a high-revenue landing page. At the same time, having a publisher’s content removed from aggregators does not guarantee an increase in direct visits that would offset the loss of potentially less lucrative referral traffic. It is thus difficult to gauge the true impact of these laws on news outlets’ bottom lines.

A core problem is that referral traffic doesn’t necessarily translate into revenue. Google claimed in 2013 that it sent more than 10 billion visits to news publishers around the world, with publishers receiving more than $9 billion through AdSense alone.63 This rose to 24 billion visits to news websites each month in 2022, according to the company.64 Amid this scale of volume, AdSense is indeed a leading source of advertising revenue for news sites, but the returns are often small. Despite claims by the tech companies, studies show that publishers are making less money even when traffic remains the same.65 In other words, despite getting more visitors from tech platforms, news outlets are not necessarily earning more money.

A core problem is that referral traffic doesn’t necessarily translate into revenue. Google claimed in 2013 that it sent more than 10 billion visits to news publishers around the world, with publishers receiving more than $9 billion through AdSense alone.63 This rose to 24 billion visits to news websites each month in 2022, according to the company.64 Amid this scale of volume, AdSense is indeed a leading source of advertising revenue for news sites, but the returns are often small. Despite claims by the tech companies, studies show that publishers are making less money even when traffic remains the same.65 In other words, despite getting more visitors from tech platforms, news outlets are not necessarily earning more money.

At present, the research on the effects of news aggregators on news publishers is inconclusive.66 An earlier study commissioned by Google estimated that referrals accounted for about 4 percent of publisher revenues in Europe.67 Facebook claimed Australian news media received “free” referrals from traffic generated on the platform that were worth $350 million in 2020.68 But independent research is needed to understand the medium- and long-term links between referral traffic and revenue, and how these links vary in different markets and countries. A better understanding of how referral versus organic traffic affects news publishers in terms of discoverability, visibility, and revenue generation would improve regulatory policy.

Nonetheless, the EU Digital Copyright Directive creates a common framework to harmonize regulation across Europe and could create a precedent that countries around the world will look to. But implementing this approach requires that specific institutions be in place to function properly. A designated third party must collect and distribute the licensing fees. Rights holders must be plugged into this system, and trust the collecting organizations, to benefit. But the question of who benefits and how to distribute fees to small publishers as well as to the journalists who actually author stories is a challenge even in advanced economies.

Spanish professional association CEDRO, which represents more than 30,000 authors and publishers, was mandated to collect the fees but was besieged by questions about how it would distribute to small rights holders, like blogs.69 The International Federation of Journalists and its national members have argued that journalists should receive some remuneration as well as the actual creators of the copyright-protected works.70

Spanish professional association CEDRO, which represents more than 30,000 authors and publishers, was mandated to collect the fees but was besieged by questions about how it would distribute to small rights holders, like blogs.69 The International Federation of Journalists and its national members have argued that journalists should receive some remuneration as well as the actual creators of the copyright-protected works.70

“The fear is that a lot of small publications will lose out because they don’t have that commercial clout to do a deal, so it reinforces the big media companies,” said Jeremy Dear, deputy general secretary of the International Federation of Journalists, which represents journalist unions and associations in more than 140 countries.71 “The problem we have with the copyright directive, and also the Australian [News Media Bargaining Code] where you have these kind of closed commercial deals, is there is a lack of transparency for the creator to know how much money the company is making.”

Discussion and Recommendations: Overarching Challenges to Redressing Regulatory Disparity

Developing countries typically lack the influence, market share, and regulatory capacity to realistically impose new requirements on global technology firms. By and large, developed countries are at the forefront of creating new frameworks to address imbalances between the news media and Big Tech. Moreover, implementing any of these approaches is not just about political will and standing up to Big Tech, but also about institutional design, legitimacy, and trust. As news media policymakers and advocates work to address this challenge in their own countries, it is important to examine the key elements that must be in place for any of these proposals to be effective.

Institutional design is a deciding factor influencing the likely success of pursuing any of these policies. A strong competition authority could pursue collective bargaining and licensing approaches; however, without a publishers’ association with the legitimacy and trust to engage in collective bargaining on behalf of the news outlets in a country, this model will fail, or risk being captured by the government. Similarly, implementing a licensing or copyright model will require industry associations and collecting agencies that could implement a monitoring and payment distribution system, which requires transparency and trust to function. Even where there are adequate publishers’ associations and existing royalty rights management organizations, there must be authorities with the competence and capacity to monitor and enforce compliance. Competition and copyright approaches require trust in the government and relevant regulators to determine who is protected, who benefits, and how that is decided in order for the system to operate effectively and fairly.

Institutional design is a deciding factor influencing the likely success of pursuing any of these policies. A strong competition authority could pursue collective bargaining and licensing approaches; however, without a publishers’ association with the legitimacy and trust to engage in collective bargaining on behalf of the news outlets in a country, this model will fail, or risk being captured by the government. Similarly, implementing a licensing or copyright model will require industry associations and collecting agencies that could implement a monitoring and payment distribution system, which requires transparency and trust to function. Even where there are adequate publishers’ associations and existing royalty rights management organizations, there must be authorities with the competence and capacity to monitor and enforce compliance. Competition and copyright approaches require trust in the government and relevant regulators to determine who is protected, who benefits, and how that is decided in order for the system to operate effectively and fairly.

All of the countries that have pursued the policies outlined in this report have a robust ecosystem of existing legal frameworks, digital rights management entities, and organized civil societies that include independent professional associations, digital rights groups, and public interest lawyers. This “is very different from a developing country where there are individuals interested in these topics but who are not connected,” said Joon-Nie Lau, director of the World Association of News Publishers (WAN-IFRA) Asia.72 Without solidarity and a collective approach, publishers cannot gain power in relation to tech platforms.

Intellectual property law is dominated by the United States and Europe, and in many cases developing countries have designed their intellectual property standards and regulations to respond to international trade agreement requirements.73 But their copyright systems are often underdeveloped or focused on other priorities.74 In many countries, the institutions needed to implement these policies may not even exist, which could pose governance challenges.

Technical training for lawmakers is needed in many countries.75 A recent United Nations report on the digital economy noted that the “lack of appropriate skill sets in government directly results in insufficient representation of technical and analytical expertise in legislative and regulatory framework development processes.”76 Furthermore, a lack of trust in authorities to regulate tech platforms can impede the adoption of new legislation.77

Technical training for lawmakers is needed in many countries.75 A recent United Nations report on the digital economy noted that the “lack of appropriate skill sets in government directly results in insufficient representation of technical and analytical expertise in legislative and regulatory framework development processes.”76 Furthermore, a lack of trust in authorities to regulate tech platforms can impede the adoption of new legislation.77

Policymakers also need better research on the effects of existing regulatory frameworks as well as how platform policies impact traffic, revenue generation, and the independence of media outlets. For example, although critics of the Australian and EU approaches have pointed to the potential negative impacts on media pluralism, information quality, and cultural diversity, there have been no empirical studies to determine whether these concerns have been borne out. Likewise, addressing the inequities in the AdTech market requires better data and research. However, the low levels of traffic and revenue generated by many news media in less developed countries mean that taxing AdTech may bring only limited benefits in these contexts.

♦ Policymakers should require the tech industry to provide more traffic data as well as how they relate to revenue and monetization for news content. Greater transparency would serve a broad range of goals including those related to strengthening media sustainability.78

♦ Media outlets need to improve their data collection and analysis so that they can better understand the links between traffic, advertising, and content monetization.

♦ Google should consider offering higher Google AdSense payments, which could lead to more immediate and meaningful support to smaller, less trafficked media, since it is far easier to use but less lucrative.79

♦ Policymakers and the donor community should support small media to “combine forces or join existing media marketplaces that aggregate traffic from multiple media companies.” This type of publisher-led news aggregator could similarly aid revenue growth without expecting them to develop the expertise or hire dedicated staff.80

♦ Direct unilateral support to media outlets by tech platforms should not be a replacement for legal regulatory frameworks that seek to create a level playing field and support independent media.

Policymaking that fails to recognize the broader economic context is bound to fail. Less developed countries face underlying economic conditions that limit access to AdTech infrastructure and pose obstacles to creating collective management organizations that can track, collect, and distribute economic gains to rights holders.

The financial disruption to the journalism sector caused by transnational tech companies and their failure to pay taxes is of growing concern to media development advocates. Amid a slew of ad hoc approaches,81 the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and Group of Twenty (G20) have agreed to impose a global minimum corporate tax on the biggest multinational platforms that’s aimed squarely at Big Tech.82 Some smaller countries are concerned, however, that the rules set to go into effect in 2023 would disproportionately benefit large countries.83 While details aren’t yet fully agreed and momentum on this proposal seems to have stalled, national-level advocacy for specific digital taxes is picking up steam in many countries.”

Governments should commit to diverting a part of any new tax revenue to support news media and public interest journalism. The news industry and publishers should vocally advocate that a portion of revenue from any new global taxation framework go to support independent and public interest journalism. Revenue-based national taxes should not be levied on individual consumers or citizens as they could negatively impact news consumption and connectivity more broadly.84 Rather they should be imposed on the companies that profit from targeted advertising. These national taxes should also contain specific carve-outs for commercial journalism outlets since they also generate revenue from digital advertising, but would face an undue financial burden given the precarious state many news outlets find themselves in. And any scheme for subsidizing journalism through state tax revenue would require considerable support and attention for the design of an independent endowment or other democratically governed mechanism for distributing those resources.

Unfortunately, many governments have a long track record of using their budgetary influence—via taxation, subsidies, grants, and advertising—to unduly influence independent media or even media capture.85 “Our headline issue in this pandemic era is the threat of media capture,” said Gibbings from the Association of Caribbean MediaWorkers. He noted that the threat was particularly acute in the Caribbean and microstates with small economic bases and thus a limited number of advertisers to complement governmental advertising.86 As a result, it is imperative to create mechanisms to ensure that the funds reach their intended beneficiaries in a way that preserves editorial independence and minimizes influence peddling.87

Addressing the media sustainability challenge in the digital era is a paramount issue with worldwide implications. As the developed economies of the West consider how to rebalance the relationship between Big Tech and the news industry, it is imperative that they take a global view and consider the implications for independent news outlets based outside of Western power centers. Ultimately, implementing any of these approaches is not just about political will, but also about institutional design, legitimacy, and trust.

Corrections

An earlier version of this report mistakenly described the US-registered New Narratives as an Australian media development organization. The report also erroneously stated that New Narratives had worked with media in South Sudan. New Narratives has worked in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Gambia, and the Pacific, but has never done work in South Sudan.

Footnotes

- Sarah Repucci and Amy Slipowitz, “Freedom in the World 2022: The Global Expansion of Authoritarian Rule,” (Washington, DC: Freedom House, February 2022), https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/2022-02/FIW_2022_PDF_Booklet_Digital_Final_Web.pdf.

- Anya Schiffrin, “Saving Journalism: A Vision for the Post-Covid World,” (Washington, DC: Konrad Adenauer Stiftng Foundation, January 11, 2022), https://www.kas.de/en/web/usa/single-title/-/content/saving-journalism; UNESCO, “Journalism Is a Public Good: World Trends in Freedom of Expression and Media Development: Global Report,” (Paris: UNESCO, 2021), https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000379826.

- Ethan Zuckerman, “The Case for Digital Public Infrastructure: The Tech Giants, Monopoly Power, and Public Discourse,” (New York: Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University, 2020), https://s3.amazonaws.com/kfai-documents/documents/7f5fdaa8d0/Zuckerman-1.17.19-FINAL-.pdf; Timothy Karr and Craig Aaron, “Beyond Fixing Facebook: How the Multibillion-Dollar Business behind Online Advertising Could Reinvent Public Media, Revitalize Journalism and Strengthen Democracy,” (Free Press, February 2019), https://www.freepress.net/sites/default/files/2019-02/Beyond-Fixing-Facebook-Final_0.pdf; Erik Martin, “Should We Tax Big Tech Companies to Pay for Local Journalism?” Protego Press (blog), 2019, https://www.protegopress.com/should-we-tax-big-tech-companies-to-pay-for-local-journalism/.

- Interview with Prue Clarke, Executive Director, New Narratives. Zoom, November 10, 2021.

- Julie Posetti, Emily Bell, and Pete Brown, “Journalism and the Pandemic: A Global Snapshot of Impacts,” (ICFJ and The Tow Center for Journalism, 2020); The Editorial Board, “Big Tech’s Reckoning over Paying for News,” Financial Times, January 27, 2021, https://www.ft.com/content/989f2837-16cb-4614-aa75-183eacd88fa6; Fernando N. Van der Vlist and Anne Helmond, “How Partners Mediate Platform Power: Mapping Business and Data Partnerships in the Social Media Ecosystem,” Big Data & Society 8, no. 1 (January 1, 2021): 20539517211025060, https://doi.org/10.1177/20539517211025061; Alex Webb, “Can Google Fix the $108 Billion News Industry It Helped Break?” Bloomberg, January 18, 2021, sec. Technology & Ideas, https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2021-01-18/can-google-facebook-fix-the-108-billion-news-industry-it-helped-break.

- Julian Thomas, “Programming, Filtering, Adblocking: Advertising and Media Automation,” Media International Australia 166, no. 1 (February 2018): 34–43, https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X17738787. See also Bernard Marr, “What Is MarTech and AdTech—and What’s the Difference?” LinkedIn, February 10, 2021, https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/what-martech-adtech-whats-difference-bernard-marr/.

- Ethan Cramer-Flood, “Duopoly Still Rules the Global Digital Ad Market, but Alibaba and Amazon Are on the Prowl,” eMarketer, Insider Intelligence, May 10, 2021, https://www.emarketer.com/content/duopoly-still-rules-global-digital-ad-market-alibaba-amazon-on-prowl.

- Google dominates the search advertising market, capturing 90 percent of search advertising revenues and charging significantly higher prices than its competitors, while Facebook accounts for more than half of all display advertising revenues and similarly earns higher revenues per user than its competitors. Together, they dominate 60 percent of all digital ad revenue, with digital advertising making up more than 55 percent of advertiser budgets, leaving the rest of the internet ecosystem to compete for the remaining 40 percent based on a market logic determined by the duopoly. Staff, “Big Tech Says Publishers Keep Majority of Ad Revenue, but Experience Suggests Otherwise,” News Media Alliance, November 16, 2020, https://www.newsmediaalliance.org/google-ad-revenue-op-ed-70-percent/.

- Amanda Meade, “Google, Facebook and YouTube Found to Make up More than 80% of Australian Digital Advertising,” The Guardian, October 23, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/media/2020/oct/23/google-facebook-and-youtube-found-to-make-up-more-than-80-of-australian-digital-advertising.

- Quoted in Imran Fazal, “Digital Publishers vs. Google,” Impact, January 25, 2022, https://www.impactonnet.com/amp/cover-story/digital-publishers-vs-google-7772.html.

- Quoted in Fazal, “Digital Publishers vs. Google.”

- For example, a survey of about 200 independent digital media found that advertising made up about a fifth of revenues amounting to about $28,000 per year. See SembraMedia, “Inflection Point International: A Study of the Impact, Innovation, Threats, and Sustainability of Digital Media Entrepreneurs in Latin America, Southeast Asia, and Africa,” (SembraMedia, November 2021); see also J.J. Robinson, Kristen Grennan, and Anya Schiffrin, “Publishing for Peanuts: Innovation and the Journalism Startup,” (New York: Columbia University, School of International and Public Affairs, 2015).

- SembraMedia, “Inflection Point International.”

- Interview with Prue Clarke, Executive Director, New Narratives. Video conference, November 10, 2021; SembraMedia, “Inflection Point International;” Robinson et al. “Publishing for Peanuts.”

- Interview with Wesley Gibbings, General Secretary, Association of Caribbean MediaWorkers, November 12, 2021.

- PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP and Incorporated Society of British Advertisers, “ISBA Programmatic Supply Chain Transparency Study,” (London: PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP and Incorporated Society of British Advertisers, May 2020), https://www.isba.org.uk/system/files/media/documents/2020-12/executive-summary-programmatic-supply-chain-transparency-study.pdf.

- United Kingdom Competition and Markets Authority, “Online Platforms and Digital Advertising: Market Study Final Report,” (London: Competition and Markets Authority, July 1, 2020), https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5efc57ed3a6f4023d242ed56/Final_report_1_July_2020_.pdf; Committee for the Study of Digital Platforms, Market Structure and Antitrust Subcommittee, “Protecting Journalism in the Age of Digital Platforms,” (Chicago: George J. Stigler Center for the Study of the Economy and the State, University of Chicago Booth School of Business, July 1, 2019), https://research.chicagobooth.edu/-/media/research/stigler/pdfs/market-structure-report.pdf?la=en&hash=E08C7C9AA7367F2D612DE24F814074BA43CAED8C; Augustine Fou, “Marketers and Publishers Are Making More Money by Using Less AdTech,” Forbes, August 7, 2020, sec. CMO Network, https://www.forbes.com/sites/augustinefou/2020/08/07/marketers-and-publishers-are-making-more-money-by-using-less-adtech/.

- United Kingdom Competition and Markets Authority, “Online Platforms and Digital Advertising”; Nic Newman, “Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2021,” (Oxford, United Kingdom: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, 2021), https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2021-06/Digital_News_Report_2021_FINAL.pdf.

- Richard Asquith, “Digital Services Tax DST Global Tracker,” VATlive, Oct 29, 2020, https://www.avalara.com/vatlive/en/vat-news/digital-services-tax-dst-global-tracker.html; Nana Ama Sarfo, “Digital Services Taxes May Be Difficult to Remove,” Forbes, March 22, 2021, sec. Tax Notes, https://www.forbes.com/sites/taxnotes/2021/03/22/digital-services-taxes-may-be-difficult-to-remove/.

- FENAJ, “FENAJ lança campanha pela taxação de grandes plataformas digitais,” FENAJ (blog), February 8, 2022, https://fenaj.org.br/fenaj-lanca-campanha-pela-taxacao-de-grandes-plataformas-digitais/.

- FENAJ, “FENAJ defende taxação de até 5% para grandes plataformas digitais,” FENAJ (blog), July 29, 2021, https://fenaj.org.br/fenaj-defende-taxacao-de-ate-5-para-grandes-plataformas-digitais/.

- Karr and Aaron, “Beyond Fixing Facebook.”

- Anya Schiffrin, Emily Bell, Julie Posetti, and Francesca Edgerton, “Finding the funds for journalism to thrive: Policy options to support media viability.” UNESCO, 2022.

- Tanja Bosch, “Lofty ideals but a failing mission. The Media Development and Diversity Agency,” in Media Diversity in South Africa: New Concepts from the Global South, ed. Julie Reid (Routledge, 2021).

- Interview with Juan Carlos Lara, Executive Director, Derechos Digitales, October 26, 2021.

- Australian Treasury, “Treasury Laws Amendment (News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code) Act 2021,” (Canberra: Australian Treasury, 2021), https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2021A00021/Html/Text, http://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2021A00021.

- News media websites often appear in Google’s “Top Stories” results, which are triggered by between 8 and 14 percent of Google searches. Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC), “ACCC Digital Platforms Inquiry: Preliminary Report,” (Canberra: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, 2018), 6, 8.

- ACCC, “ACCC Digital Platforms Inquiry.”

- Celina Ribeiro, “Can Australia Force Google and Facebook to Pay for News?” Wired, August 30, 2020, https://www.wired.com/story/can-australia-force-google-facebook-pay-news/.

- James Clayton, “Google Threatens to Withdraw Search Engine from Australia,” BBC News, January 22, 2021, sec. Australia, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-55760673.

- Melissa Clarke, Jeremy Story Carter, and staff, “Facebook Ban Potentially ‘Dangerous’ for Indigenous Vaccine Rollout,” ABC News, February 18, 2021, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-02-18/facebook-ban-feared-dangerous-for-indigenous-vaccine-rollout/13166658; “Community Broadcasting Sector News Disproportionately Impacted by Facebook’s Decision,” Radioinfo, February 18, 2021, https://radioinfo.com.au/news/community-broadcasting-sector-news-disproportionately-impacted-facebooks-decision/.

- IndigenousX, “Public Statement – First Nations Voices Restricted by Facebook – James Saunders,” February 18, 2021, https://indigenousx.com.au/public-statement-first-nations-voices-restricted-by-facebook/.

- Bill Grueskin, “Millions of Dollars for News, Shrouded in Mysterious Deals,” (Chippendale, Australia: The Judith Neilson Institute, March 10, 2022), https://jninstitute.org/news/millions-of-dollars-for-news-shrouded-in-mysterious-deals/.

- “Public-Interest Publishers Band Together to Seek Deal with Google and Facebook,” Australian Rural & Regional News,” November 23, 2021, https://arr.news/2021/11/23/public-interest-publishers-band-together-to-seek-deal-with-google-and-facebook/.

- Grueskin, “Millions of Dollars for News, Shrouded in Mysterious Deals.”

- Lucia Moses, “Uh-Oh, Some Publishers See a Drop in Facebook Traffic,” Digiday, April 8, 2016, https://digiday.com/media/publishers-just-saw-decline-facebook-traffic/; Anthony Ha, “LittleThings Blames Its Shutdown on Facebook Algorithm Change,” TechCrunch, February 28, 2018, https://social.techcrunch.com/2018/02/28/littlethings-shutdown/; Max Willens, “Hope Springs Eternal for Publishers Trying Yet Again with Facebook News,” Digiday, October 24, 2019, http://ec2-34-225-151-148.compute-1.amazonaws.com/media/more-long-term-commitment-hope-springs-eternal-for-news-publishers-on-the-eve-of-facebook-news-launch/.

- Kelsey Sutton, “Facebook Video Ad Metric Lawsuit Prompts Publishers to Revisit the ‘Pivot to Video,’” Ad Week, October 19, 2018, https://www.adweek.com/performance-marketing/facebook-video-ad-metric-lawsuit-prompts-publishers-to-revisit-the-pivot-to-video/; Will Oremus, “The Big Lie behind the ‘Pivot to Video,’” Slate, October 18, 2018, https://slate.com/technology/2018/10/facebook-online-video-pivot-metrics-false.html; Alexis C. Meyer and Robinson Madrigal, “How Facebook’s Chaotic Push into Video Cost Hundreds of Journalists Their Jobs,” The Atlantic, October 18, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2018/10/facebook-driven-video-push-may-have-cost-483-journalists-their-jobs/573403/.

- Mark Zuckerberg, “One of our big focus areas for 2018 is making sure the time we all spend on Facebook is time well spent,” Facebook, January 11, 2018, accessed February 23, 2022, https://www.facebook.com/zuck/posts/10104413015393571; Kevin Tran, “Publishers Are Trying to Navigate Facebook’s Algorithm Change,” Business Insider, June 27, 2018, https://www.businessinsider.com/publishers-navigate-facebooks-algorithm-change-2018-6.

- Treasury Laws Amendment (News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code) Act 2021, Pub. L. No. 21, 62 (2021), https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2021A00021.

- Agustinus Beo Da Costa and Stanley Widianto, “Indonesia Mulls Media Bill Seeking Fairer Share from Big Tech,” Reuters, November 23, 2021, sec. Technology, https://www.reuters.com/technology/indonesia-mulls-media-bill-seeking-fairer-share-big-tech-2021-11-23/.

- Conversation with Brazilian journalist Patricia Mello Campo, Falho de S. Paulo, at the 2022 International Journalism Festival, Perugia, Italy. See also Patricia Campos Mello, “An Unholy Coalition Torpedoes Social Media Reform Legislation in Brazil,” Poynter, May 17, 2022, https://www.poynter.org/business-work/2022/an-unholy-coalition-torpedoes-social-media-reform-legislation-in-brazil/.

- Interview with Alvin Ntibinyane, Managing Partner, INK Centre for Investigative Journalism, Botswana. Video conference, January 24, 2022.

- Interview with Juan Carlos Lara, Executive Director, Derechos Digitales, October 26, 2021.

- Shrimi Choudhary, “Competition Commission of India Orders Google Inquiry after News Publishers Complain,” The Economic Times, January 7, 2022, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/media/entertainment/media/competition-commission-of-india-orders-google-inquiry-after-news-publishers-complain/articleshow/88762265.cms.

- Several attempts to contact the Digital News Publishers Association via its website, email, and direct outreach to members were unsuccessful.

- This gives publishers the right to exploit and enforce copyright based on the rights transferred to them by authors. Giuseppe Colangelo and Valerio Torti, “Copyright, Online News Publishing and Aggregators: A Law and Economics Analysis of the EU Reform,” International Journal of Law and Information Technology 27, no. 1 (March 1, 2019): 75–90, https://doi.org/10.1093/ijlit/eay019.

- As the World Intellectual Property Organization explains: “Managing copyright and related rights individually may not always be realistic. An author, performer or producer, for instance, cannot contact every single radio station to negotiate licenses and remuneration for the use of their songs. On the other side, it is not practical for a radio station to seek specific permission from every author, performer and producer for the use of each song. CMOs (Collective Management Organization) facilitate rights clearance in the interest of both parties and economic reward for rights holders.” See “Collective Management of Copyright and Related Rights,” World Intellectual Property Organization, https://www.wipo.int/copyright/en/management/, accessed March 31, 2022.

- Such as the Global Data Protection Regulation or the so-called Right to Be Forgotten.

- Eleonora Rosati, “Neighbouring Rights for Publishers: Are National and (Possible) EU Initiatives Lawful?” IIC – International Review of Intellectual Property and Competition Law 47, no. 5 (August 1, 2016): 569–94, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40319-016-0495-4.

- “Germany’s Top Publisher Bows to Google in News Licensing Row,” Reuters, November 5, 2014, sec. Technology News, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-google-axel-sprngr-idUSKBN0IP1YT20141105; Michael Filtz, “Major German News Sites Stay in Google News, despite Protesting against It.” ZDNet, August 2, 2013, sec. The German View, https://www.zdnet.com/article/major-german-news-sites-stay-in-google-news-despite-protesting-against-it/.

- The European Court of Justice determined in 2019 that the German law was invalid due to a procedural error. See Tom Hirshe, “ECJ Rules German Ancillary Copyright for Press Publishers to Be Ineffective!” IGEL – Initiative against an Ancillary Copyright, December 9, 2019, https://ancillarycopyright.eu/news/2019-09-12/ecj-rules-german-ancillary-copyright-press-publishers-be-ineffective.

- “Argumentación económica sobre la propuesta de modificación de la LPI en lo relativo a la agregación de contenidos informativos,” (Madrid: Coalition Prointernet, July 2014); Glyn Moody, “Spain’s Ill-Conceived ‘Google Tax’ Law Likely to Cause Immense Damage to Digital Commons and Open Access,” Techdirt, August 12, 2014, https://www.techdirt.com/articles/20140811/05564728172/spains-ill-conceived-google-tax-law-likely-to-cause-immense-damage-to-digital-commons-open-access.shtml.

- The Spanish approach also undermined Creative Commons licensing and imposed fines on infringing websites.

- María González, “PRISA Dice Que Renuncia a Cobrar El Canon AEDE… Que, Por Cierto, Es Irrenunciable,” Genbeta (blog), July 6, 2015, https://www.genbeta.com/actualidad/prisa-dice-que-renuncia-a-cobrar-el-canon-aede-que-por-cierto-es-irrenunciable.

- “Nace la Coalición Pro Internet,” Coalición Pro Internet, https://www.coalicionprointernet.com/?page_id=7#APOYOS, accessed January 20, 2022; gallir, “Posicionamiento de Menéame sobre la ‘tasa a agregadores’ de la nueva Ley de Propiedad Intelectual,” Menéame (blog), February 16, 2014, https://blog.meneame.net/2014/02/16/posicionamiento-de-meneame-sobre-la-tasa-a-agregadores-de-la-nueva-ley-de-propiedad-intelectual/; Alberto Gutiérrez García and Hugo Hernández Cobos, “Impacto del Nuevo Artículo 32.2 de la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual: Informe para la Asociación Española de Editoriales de Publicaciones Periódicas (AEEPP),” (Madrid: NERA Economic Consulting, July 9, 2015); Susan Athey, Markus Mobius, and Jeno Pal, “The Impact of Aggregators on Internet News Consumption,” (Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, April 2021), https://doi.org/10.3386/w28746.

- News Media Alliance, “The Effects of the Ancillary Right for News Publishers in Spain and the Resulting Google News Closure,” (Arlington, VA: News Media Alliance, November 2019), https://www.newsmediaalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Final-Revised-Spain-Report_11-7-19.pdf.

- María González, “CEDRO Ya Negocia Con Agregadores Las Tarifas Del Canon AEDE: Si Tienen 10.000 Visitas Diarias, Pagarán 185.000€ Anuales,” Xataka (blog), February 7, 2017, https://www.xataka.com/legislacion-y-derechos/cedro-ya-negocia-con-algunos-agregadores-las-tarifas-del-canon-aede-0-05044854eu-por-usuario-activo-al-dia; Manuel Ángel Méndez, “Nuevo intento de imponer el canon AEDE: piden a Menéame 2,5 millones de euros al año,” elconfidencial.com, February 7, 2017, sec. Tecnología, https://www.elconfidencial.com/tecnologia/2017-02-07/canon-aede-meneame-internet-facebook-agregadores_1327333/.

- Sergio Agudo, “Así Es Upday, El Agregador de Noticias Para Móviles Samsung Que Sí Pagará El Canon AEDE,” Genbeta, February 16, 2017, https://www.genbeta.com/a-fondo/asi-es-upday-el-agregador-de-noticias-para-moviles-samsung-que-si-pagara-el-canon-aede; Sergio Agudo, “Los Editores Se Pagan La ‘Tasa Google’ a Sí Mismos Para Legitimar El Canon AEDE,” Genbeta (blog), June 29, 2017, https://www.genbeta.com/actualidad/los-editores-se-pagan-la-tasa-google-a-si-mismos-para-legitimar-el-canon-aede.

- Méndez, “Nuevo intento de imponer el canon AEDE”; González, “CEDRO Ya Negocia Con Agregadores Las Tarifas Del Canon AEDE.”

- Marcos Merino, “Los editores españoles demandan a Google por el impago de 1,1 millones de euros del canon que debe abonar por su servicio Discover,” Genbeta, November 11, 2020, https://www.genbeta.com/actualidad/editores-espanoles-demandan-a-google-impago-1-1-millones-euros-canon-que-debe-abonar-su-servicio-discover; Marcos Merino, “Google Discover No Tendrá Que Abonar El Canon AEDE, Mientras Que CEDRO Deberá Pagar En Costas La Mitad de Lo Que Ingresó Por Éste En 2020,” Genbeta, January 5, 2022, https://www.genbeta.com/actualidad/google-discover-no-tendra-que-abonar-canon-aede-cedro-debera-pagar-costas-mitad-que-ingreso-este-2020.

- Laura Hazard Owen, “After 8 years, Google News Returns to Spain,” Nieman Lab, June 22, 2022, https://www.niemanlab.org/2022/06/after-8-years-google-news-returns-to-spain/.

- Newman, “Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2021.”

- Luis Collado, “Google y los editores,” Blog Oficial de Google España (blog), February 28, 2014, https://espana.googleblog.com/2014/02/google-y-los-editores.html.

- Sundar Pitchai, “Our $1 Billion Investment in Partnerships with News Publishers,” Google: Google News Initiative (blog), October 1, 2020, https://blog.google/outreach-initiatives/google-news-initiative/google-news-showcase/.

- PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP and Incorporated Society of British Advertisers, “ISBA Programmatic Supply Chain Transparency Study”; Staff, “Big Tech Says Publishers Keep Majority of Ad Revenue, but Experience Suggests Otherwise,” News Media Alliance, November 16, 2020, https://www.newsmediaalliance.org/google-ad-revenue-op-ed-70-percent/.

- Athey et al., “The Impact of Aggregators on Internet News Consumption”; Rosati, “Neighbouring Rights for Publishers”; Colangelo and Torti, “Copyright, Online News Publishing and Aggregators”; Lesley Chiou and Catherine Tucker, “Content Aggregation by Platforms: The Case of News Media,” (Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2015), http://www.nber.org/papers/w21404.pdf; P. Madsen and J. Andsager, “Aggregating Agendas: Online News Aggregators as Agenda Setters,” Paper presented to the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication Annual Conference, 2012, http://www.mapor.org/confdocs/absandpaps/2011/2011_papers/1a1Madsen.pdf; M. Calin, C. Dellarocas, E. Palme, and J. Sutanto, “Attention Allocation in Information-Rich Environments: The Case of News Aggregators,” (Boston: Boston University School of Management, 2013), http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2225359.

- Deloitte, “The Impact of Web Traffic on Revenues of Traditional Newspaper Publishers: A Study for France, Germany, Spain, and the UK,” (UK: Deloitte LLP, March 2016).

- Richard Waters, Hannah Murphy, and Alex Barker, “Big Tech versus Journalism: Publishers Watch Australia Fight with Bated Breath,” Financial Times, February 18, 2021, http://www.proquest.com/docview/2503121052/citation/A65CB21A0FD945D4PQ/1.

- María González, “‘Tasa Google’: Si tienes un blog también te afecta, solo que otros la cobrarán por ti,” Genbeta (blog), February 16, 2014, https://www.genbeta.com/actualidad/tasa-google-si-tienes-un-blog-tambien-te-afecta-solo-que-otros-la-cobraran-por-ti.

- US Copyright Office, “Publishers’ Protection Study: Notice and Request for Public Comment: National Writers Union,” (Washington, DC: Regulations.gov, December 2, 2021), https://www.regulations.gov/comment/COLC-2021-0006-0020.

- Interview with Jeremy Dear, Deputy General Secretary, International Federation of Journalists. Zoom, January 31, 2022.

- Interview with Joon-Nie Lau, Director, World Association of News Publishers (WAN-IFRA) Asia, October 28, 2021.

- There are also a range of counter hegemonic and anti-colonialist critiques related to this fact, which is particularly relevant with respect to new technology given that US firms occupy nine of the top 10 positions. See Mariana G. Valente, “Digital Technologies and Copyright: International Trends and Implications for Developing Countries,” Digital Pathways Paper Series, (Oxford, United Kingdom: Pathways for Prosperity Commission, March 2020), https://pathwayscommission.bsg.ox.ac.uk/Mariana-Valente-digital-technologies-and-copyright; Anu Bradford, Adam Chilton, Katerina Linos, and Alexander Weaver, “The Global Dominance of European Competition Law over American Antitrust Law,” Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 16, no. 4 (2019): 731–66, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/emplest16&i=736; Jade Kouletakis, “Decolonising Copyright: Reconsidering Copyright Exclusivity and the Role of the Public Interest in International Intellectual Property Frameworks,” GRUR International 71, no. 1 (January 1, 2022): 24–33, https://doi.org/10.1093/grurint/ikab099; Emmanuel Hassan, Ohid Yaqub, and Stephanie Diepeveen, “Intellectual Property and Developing Countries: A Review of the Literature,” (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2010).

- Many developing countries have focused on building intellectual property capacity to address public health, pharmaceuticals, and technology transfer, among other topics, and to meet commitments outlined in the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, which did not have much to say about the platform economy and did not cover ancillary/neighboring rights or publisher licensing. See Jean-Frédéric Morin and Jenny Surbeck, “Mapping the New Frontier of International IP Law: Introducing a TRIPs-Plus Dataset,” World Trade Review 19, no. 1 (January 2020): 109–22, http://dx.doi.org.proxyau.wrlc.org/10.1017/S1474745618000460; Michael Blakeney and Getachew Mengistie, “Intellectual Property Policy Formulation in LDCs in sub-Saharan Africa,” African Journal of International and Comparative Law 19, no. 1 (2011): 66–98, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/afjincol19&i=66; Interview with Elena Perotti, Executive Director, Public Affairs and Media Policy, World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers. Video conference, October 28, 2021.

- Interview with Alvin Ntibinyane, Managing Partner, INK Centre for Investigative Journalism, Botswana. Video conference, January 24, 2022.

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), “Digital Economy Report 2021,” (Geneva: UNCTAD, 2021), xxi.

- Akintola Olaniyan and Ufuoma Akpojivi, “Transforming Communication, Social Media, Counter-Hegemony and the Struggle for the Soul of Nigeria,” Information, Communication & Society 24, no. 3 (February 17, 2021): 422–37, https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1804983.

- Self-reporting and internal research is inadequate given the limited access to platform data, the lack of transparency and accountability with respect to the company’s own research, their retaliation against employees who seek to share research findings, and the overreliance on whistleblowers and investigative journalists to find out what companies know. See Karen Hao, “The Fight to Reclaim AI,” MIT Technology Review, August 7, 2021, https://proxyau.wrlc.org/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=150884598&site=ehost-live&scope=site; Queenie Wong, “Facebook Disables Accounts Tied to NYU’s Research into Political Ads,” CNET, August 4, 2021, https://www.cnet.com/news/facebook-disables-accounts-tied-to-nyus-research-into-political-ads/; Craig Silverman, Ryan Mac, and Pranav Dixit, “‘I Have Blood on My Hands’: A Whistleblower Says Facebook Ignored Global Political Manipulation,” BuzzFeed News, September 14, 2020, https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/craigsilverman/facebook-ignore-political-manipulation-whistleblower-memo; Susan Benesch, “Nobody Can See into Facebook,” The Atlantic, October 30, 2021, sec. Ideas, https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/10/facebook-oversight-data-independent-research/620557/.

- Interview with Prue Clarke, Executive Director, New Narratives. Video conference, November 10, 2021; Tania Lucía Cobos, “Las percepciones y experiencias sobre Google News de los editores de medios noticiosos latinoamericanos indexados en las ediciones de Colombia y México,” Estudios Sobre el Mensaje Periodistico 24, no. 2 (2018): 1183–98, http://dx.doi.org.proxyau.wrlc.org/10.5209/ESMP.62208; However, the unintended consequence of focusing on Google AdSense could end up reorienting journalism toward more traffic-generating coverage and fuel disinformation and junk news. Joshua A. Braun and Jessica L. Eklund, “Fake News, Real Money: Ad Tech Platforms, Profit-Driven Hoaxes, and the Business of Journalism,” Digital Journalism 7, no. 1 (January 2, 2019): 1–21, https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2018.1556314; Olaniyan and Akpojivi, “Transforming Communication, Social Media, Counter-Hegemony and the Struggle for the Soul of Nigeria”; Interview with Janine Warner, Executive Director, SembraMedia. In person, April 10, 2022.

- SembraMedia, “Inflection Point International.”

- Countries around the world have imposed digital service taxes on foreign tech services and online advertising that are designed to improve competition and fairness but which the United States has labeled as discriminatory. See Asquith, “Digital Services Tax DST Global Tracker;” Sarfo, “Digital Services Taxes May Be Difficult to Remove;” KPMG, “U.S. Findings from Investigations of Digital Services Taxes in India, Italy, Turkey,” (Washington, DC: KPMG, January 7, 2021), https://home.kpmg/us/en/home/insights/2021/01/tnf-us-findings-investigations-digital-services-tax-india-italy-turkey.html.

- Richard Partington, “OECD Deal Imposes Global Minimum Corporate Tax of 15%,” The Guardian, October 8, 2021, sec. Business, https://www.theguardian.com/business/2021/oct/08/oecd-deal-imposes-global-minimum-corporate-tax-of-15.

- Alex Cobham, “A Corporate Tax Reset by the G7 Will Only Work If It Delivers for Poorer Nations Too,” The Guardian, June 3, 2021, sec. Opinion, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/jun/03/corporate-tax-reset-g7-poorer-nations.

- Juliet Nanfuka, “How Social Media Taxes Can Burden News Outlets: The Case of Uganda,” CIMA Digital Report, (Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance, May 14, 2019), https://www.cima.ned.org/publication/how-social-media-taxes-can-burden-news-outlets-the-case-of-uganda/.

- Anya Schiffrin, Center for International Media Assistance, National Endowment for Democracy (U.S.), Columbia University, and Nadia Diuk Collection (Library of Congress), eds, “In the Service of Power: Media Capture and the Threat to Democracy,” (Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance, 2017).

- Interview with Wesley Gibbings, Association of Caribbean MediaWorkers. Video conference, November 12, 2021.

- For example, in countries where government advertising is allocated to reward and punish journalism, defining beneficiaries of any new tax would be susceptible to similar dynamics. Marius Dragomir, “Control the Money, Control the Media: How Government Uses Funding to Keep Media in Line,” Journalism 19, no. 8 (August 2018): 1131–48, https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884917724621; Servet Yanatma, “Media Capture and Advertising in Turkey: The Impact of the State on News,” Journalist Fellows’ Papers, (Oxford, United Kingdom: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, 2016), https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/our-research/media-capture-and-advertising-turkey-impact-state-news.