Key Findings

Independent media around the world are in crisis. Failing market conditions, the loss of advertising revenue to big tech, and autocratic encroachment in the media sector have made it difficult for even the best news outlets to protect their editorial independence and remain financially resilient. In countries with high levels of government control in the media, independent journalism is in an even worse state. Given the immense challenges independent journalism is facing, greater engagement of the private sector is critical to help save it. The business community also has much to gain as a healthy information space can strengthen markets and protect brand integrity.

Case studies in Czechia, Romania, and Serbia show that the private sector can and does play a role in protecting information integrity. While most initiatives are modest in scope, they provide inspiration for engaging the private sector to help combat information disorder and solve the myriad challenges independent media in the region face.

– Despite a growing awareness that a healthy information space is essential for business to thrive, many private sector actors are hesitant to support independent journalism out of lingering mistrust and fear of government retaliation.

– The private sector’s contribution to protecting information integrity in Central Europe has been strikingly modest. Understanding what motivates the business community and designing new models of support are crucial for incentivizing private sector support.

– There is no single, universally applicable model for unlocking private capital and enhancing the role the private sector can play in supporting a healthy information space. The particularities of the private sector, as well as the local political and economic context, greatly influence the forms of engagement and levels of support businesses can provide.

Overview: Why Should the Private Sector Care?

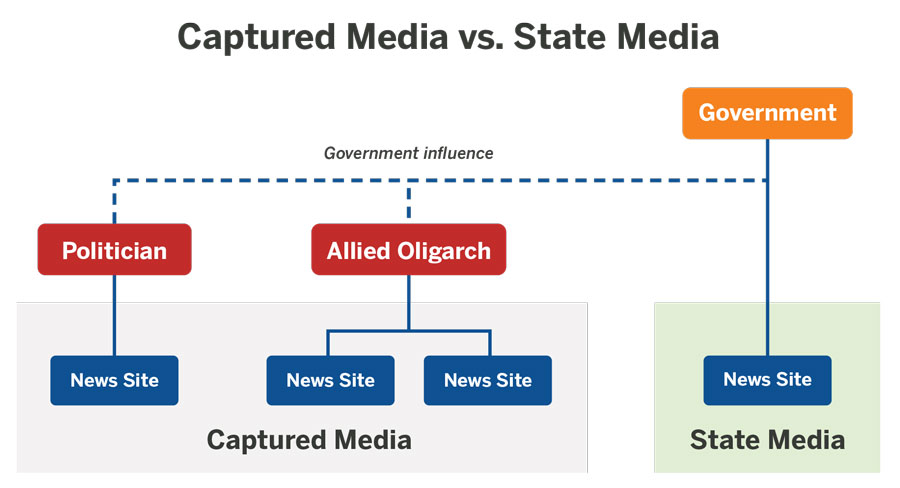

Independent media around the world are in crisis. Failing market conditions, the loss of advertising revenue to big tech, and autocratic encroachment in the media sector leading to financial strangulation and policies meant to muzzle a free press have made it difficult for even the best news outlets to protect their editorial independence and remain financially resilient. In countries with high levels of government control in the media, independent journalism is in an even worse state. Besides the official state-controlled media, the government has rapidly extended its influence over large swathes of the private media sphere, pushing independent journalism to the fringes. In such captured environments,1 the space for independent media is dramatically shrinking, affecting the quality of information that people have access to.

In Central and Eastern Europe, oligarchic takeover of the media sphere and a flood of mis- and disinformation are further eroding the region’s information space. Donor funding through official development assistance to the media has not kept pace with these challenges, stagnating at around 0.3 percent of all official development assistance between 2010 and 2019.2

To date, the private sector has not been a prominent actor in protecting information integrity and supporting independent media in developing countries and democracies under threat. Yet, given the immense challenges these countries face, their role is crucial for safeguarding independent media and addressing threats to the information space.

This report builds off research conducted in Czechia, Romania, and Serbia by an international team of media experts. The research aimed to identify inspiring and impactful ways that the private sector in these countries is engaging in efforts to counter disinformation and bolster independent journalism. It sought to draw out what motivates the business community to meaningfully support information integrity, and what prevents greater involvement of this group (see Methodology in the Annex).

The media sectors in the three countries share much, including a similar trajectory of reform following the fall of communism in the region, but also the challenges media capture has wrought on media independence and freedom over the past decade. Serbia is an extreme example of media capture, with special interest groups close to populist President Aleksandar Vučić controlling a vast number of media companies in the country. In Romania, state control is weaker than in other Central and Eastern European nations, yet its media market is a farrago of competing political interests, some of them linked to state authorities, that heavily affect journalistic independence. With arguably the most vibrant media market in the region, Czechia has experienced a steep decline in media freedom and independence since 2014, when oligarchs, many of them linked to political parties and political interests, took over numerous independent outlets. The rising media capture in the country has eroded editorial independence, causing journalists to leave news organizations and start their own journalistic projects and outlets. These initiatives provide a foundation to reclaim the media space from oligarchic control, but many of them are small and unsustainable.

Who's Afraid of Independent Journalism

“Without independent journalism, we won’t know who we depend on,”3 warned František Dostálek, a veteran entrepreneur who cofounded the Czech branch of the global auditing giant KPMG. Dostálek and other business leaders were concerned about the growing politicization of news media ownership in Czechia, discussing the issue at length during informal meetings at the Prague Business Club.4 In 2016, they decided to wield their power to wrestle independent journalism from political and oligarchic control, and in August 2016, established the Endowment Fund for Independent Journalism (Nadační fond nezávislé žurnalistiky, NFNŽ) in Czechia.

The fund aimed to redress the growing problem of media capture in the country. The issue was so widespread that a popular joke circulated among Czech journalists at the time: one morning, the wife of Andrej Babiš, a wealthy business owner, sends him out to buy her a newspaper. When he returns 10 minutes later, a radiantly smiling Babiš tells his wife: “Sweetheart, I bought you not one, but two newspapers.”

At the root of the joke was Babiš’s 2013 purchase of Mafra, a leading publisher running Mladá fronta Dnes (Youth Front Today) and Lidové noviny (The People’s Newspaper), two major newspapers in Czechia. The deal sent a ripple of unease through the country’s journalistic community. Babiš was one of the richest business owners in Czechia with an estimated net worth in excess of $2 billion. His political influence was also on the rise. In 2014, less than two years after founding his own political party, Babiš became minister of finance and deputy prime minister.

Following Mafra’s purchase, Babiš promised he would not interfere with the editorial agenda of the newspapers he acquired. But independent journalists and advocates were skeptical. Their worst predictions came true. The following year, several journalists at the Babiš-owned media outlets left amid allegations of editorial freedom violations.5

Babiš’s entry in the media provided inspiration to other Czech oligarchs. Between 2013 and 2015, two powerful financial groups took over Czech News Center, publisher of the tabloid daily Blesk, and Vltava Labe Media, the largest regional press publisher in the country. Together, Mafra, Czech News Center, and Vltava Labe Media captured 88 percent of newspaper readership in Czechia.6 Combined with a rising wave of disinformation, the oligarchic influence in Czechia led to a severe deterioration of the country’s information space.

Mafra’s takeover raised widespread concerns about press freedom and independence—even outside of the journalism community. As more media houses were bought by oligarchs, an increasing number of Czech businesspeople began to worry about the impact that the shrinking space for independent journalism would have on the nation’s democracy, which indirectly threatened their own businesses. This concern led Dostálek and others to join forces to help save independent journalism.

Since its establishment, the NFNŽ has made a significant impact. Without its support, a series of investigations could not have been carried out and several newly established news outlets would not have survived. As more businesses joined in, the endowment became a key source of funding for independent journalism. Since its establishment, it has doled out over €1.25 million ($1.34 million), a significant amount for local standards, in the form of direct support to more than 110 media projects, such as investigative journalism initiatives.

The fund’s long-term strategy and the active involvement of journalists in running it have ensured the endowment’s success and impact. Another important factor was the buy-in from a significant number of business actors who understood the fund’s role in staving off the negative effects of propaganda and disinformation, safeguarding the overall health of the country’s infosphere, and, ultimately, protecting democracy in their country.

“From an entrepreneurial point of view, we need a stable democratic society for business development,” said Václav Muchna, owner of Y Soft, a Czech software manufacturer.7 “If we go Hungary’s way, that means the end of our business in the long term. We either develop a stable business environment or relocate the company,” added Muchna, also an NFNŽ cofounder, alluding to the highly captured media environment in Hungary, where a sizable chunk of the media sector is controlled by the autocratic government of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán.

At a time when the space for independent journalism is rapidly shrinking, support from private businesses is crucial for the media sector. In the same vein, a healthy media ecosystem is an indispensable condition for ethical businesses to thrive. The two need one another. But mutual distrust, and a lack of knowledge between journalists and corporate actors, has limited collaboration.

The Private Sector and Journalism: An Inseparable Couple?

Independent media across the globe are in financial distress. Particularly in countries with weak market conditions and poor safeguards for media freedom and independence, the news media are increasingly unable to fulfill their public interest mandate. A vibrant, independent media sector is no longer possible in many countries without the financial support of a broad range of private sector actors. But, other than a few exceptions, private corporations are largely apathetic to their role in promoting a healthy information space. In illiberal countries, and those where politics and business are intertwined, the business community largely avoids the media sector altogether, fearful of retribution that could come from openly supporting oppositional news outlets. Starved of support, those outlets are left vulnerable to capture or are eventually forced to shut their doors.

The catastrophic state of independent media is due to several interlinking factors. Media outlets worldwide experienced dramatic income losses resulting from a series of economic crises that began in 2007.8 Dwindling ad spending prompted media players to slash their costs and trim their operations, resulting in significant job losses in the industry.9 Some media companies never recovered from these shocks.10 Shifts in digital technologies, which predated the 2007 economic crisis, radically reshaped the media ecosystem and the logic of news distribution.11 Rapidly growing tech companies attracted billions of people to their platforms, allowing them to cement their dominance in the advertising market, a trend that further eroded the profitability of the news industry.12

The catastrophic state of independent media is due to several interlinking factors. Media outlets worldwide experienced dramatic income losses resulting from a series of economic crises that began in 2007.8 Dwindling ad spending prompted media players to slash their costs and trim their operations, resulting in significant job losses in the industry.9 Some media companies never recovered from these shocks.10 Shifts in digital technologies, which predated the 2007 economic crisis, radically reshaped the media ecosystem and the logic of news distribution.11 Rapidly growing tech companies attracted billions of people to their platforms, allowing them to cement their dominance in the advertising market, a trend that further eroded the profitability of the news industry.12

At the same time, governments that are intolerant of a free press have been able to exploit this challenging environment. They have stepped up their influence in the media, channeling hefty amounts of public funds to both state and private media in the form of advertising or government subsidies as a way to control their editorial coverage.13 And, in a growing number of countries, governments use politically aligned businesses to take over entire media operations. Excessively strong government intervention in the media, often through economic means, has a baleful effect on editorial independence and distorts market competition, with dire consequences for media sustainability. It discourages investments in the media and reduces the impact of donor organizations, which have far fewer resources than governments.14 Very often, these trends lead to “economic censorship,” where journalists avoid certain topics or even change their editorial coverage to satisfy direct or implicit requests from advertisers or owners.15

Finally, a culture of not paying for news content proliferates as people either refuse to pay for news under the impression that the internet brims with free content or, in less affluent societies, cannot afford to buy a news service subscription.16 In countries where the government lavishly sponsors free content, people have no incentive to pay for news products, even though most of the freely available content is propaganda. Particularly in developing and democratizing countries, a combination of challenging market conditions, rudimentary or absent market regulations, weak or nonexistent safeguards for independent journalism, and very low purchasing power prevents independent media from becoming financially viable.17

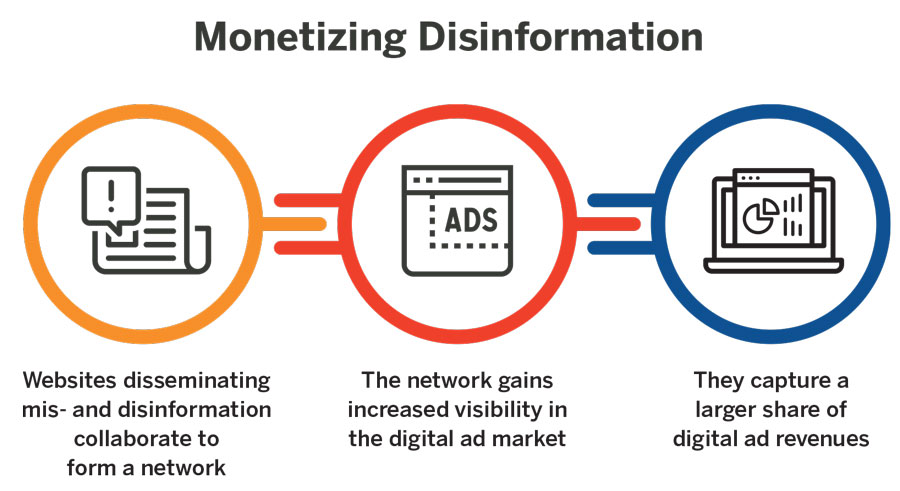

The digital transformations and economic downturns that have challenged the financial sustainability of the media sector are not the only factors threatening the information space in Central and Eastern Europe. The rapid and staggering spread of disinformation has dampened public trust18 in news and damaged the business side of the industry. Unethical media outlets spreading disinformation increasingly compete for audiences and funding with trustworthy, independent news outlets, a trend that compounds the economic pains news media are experiencing. For example, advertising is known to be one of the primary sources of revenue for most misinformation websites19 in Central and Eastern Europe. These platforms attract large audiences, and advertisers take notice of where ad placements can reach the most eyes. “Advertising is such a major source of cash for misinformation channels that in Romania and Hungary, some of these websites are difficult to navigate due to the overabundance of ads,” according to a study covering misinformation in the region.20

In Romania, networks of misinformation websites have been created at a frantic pace as a strategy to attract more revenue by boosting the advertising power of individual sites. Such networks allow cross-posting and cross-advertising, which in the end leads to increased distribution of content to a larger audience. “Recycling content and monetizing it to the maximum is the ultimate form of turning information into a commodity,” says Dumitrița Holdiș, who researches misinformation in Romania.21

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, a small Balkan nation of 3.5 million people, most misinformation websites that have emerged in recent years are primarily profit-oriented, the bulk of their funds being generated through AdSense—the ad sale program owned by the tech giant Google.22

While such market incentives enable the spread of unethical content, there is still potential to change them, and some private sector actors have signaled their concern. An increasing number of companies are working to dissociate23 themselves from websites known to spread disinformation and propaganda, which is a major step forward.24

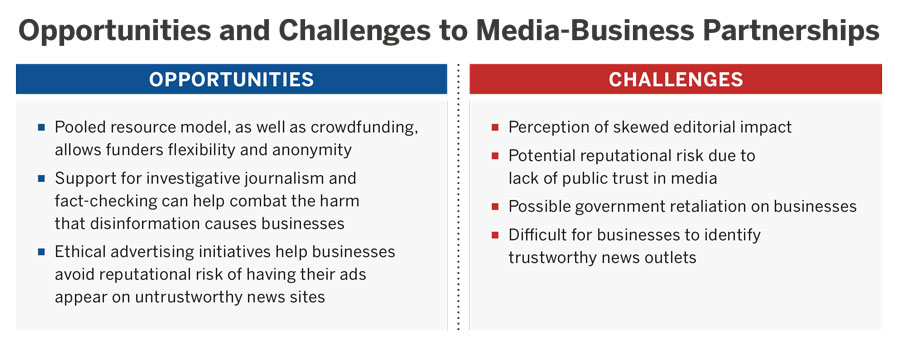

Those in the business community who have stepped up to support information integrity have a variety of reasons for doing so. First, in spite of still limited awareness of the impact of disinformation among private sector actors, there is growing recognition that a healthy information space is essential for good governance, which in turn helps markets thrive by promoting accountability and transparency, curbing corruption, and promoting a vibrant civil society. Second, an uninformed or badly informed society is hardly a propitious environment for businesses to thrive. “We have a deep belief in the need for independent journalism […] because if we as citizens do not have the best possible information, then we will also make bad decisions in elections and in other situations,” said Martin Vohánka, owner of Eurowag, a Czech transportation provider that has invested in the news outlet Deník N (Diary of N).25 Third, to navigate the local political and economic context, businesses need access to independently produced news and information. “We can commission market studies and expert reports to boost our competitive edge, but we can only thrive in a healthy business environment, and that can only exist in a society served by varied independent sources of information,” said a manager working for a telco with operations across Eastern Europe.26 Finally, disinformation can harm a company’s brand, and recent studies show that advertising in trusted media can boost brand integrity.27 In media markets where information is weaponized and mis- and disinformation are rampant, businesses find it extremely difficult to protect their brands, names, and reputations.

Despite the threat that a compromised information space poses to corporate brands, supporting independent journalism in environments with captured business and media markets, where news is often entwined with political interests, can be extremely challenging for private companies. In these environments, independent media compete with government-supported businesses that benefit from a series of incentives, a situation that distorts the competitive playing field. They also struggle with galloping regulatory costs, which can increase if the government finds a news outlet to be acting against its interests. In such environments, supporting independent journalism, which is usually critical of the regime, is most likely to have negative repercussions for businesses.

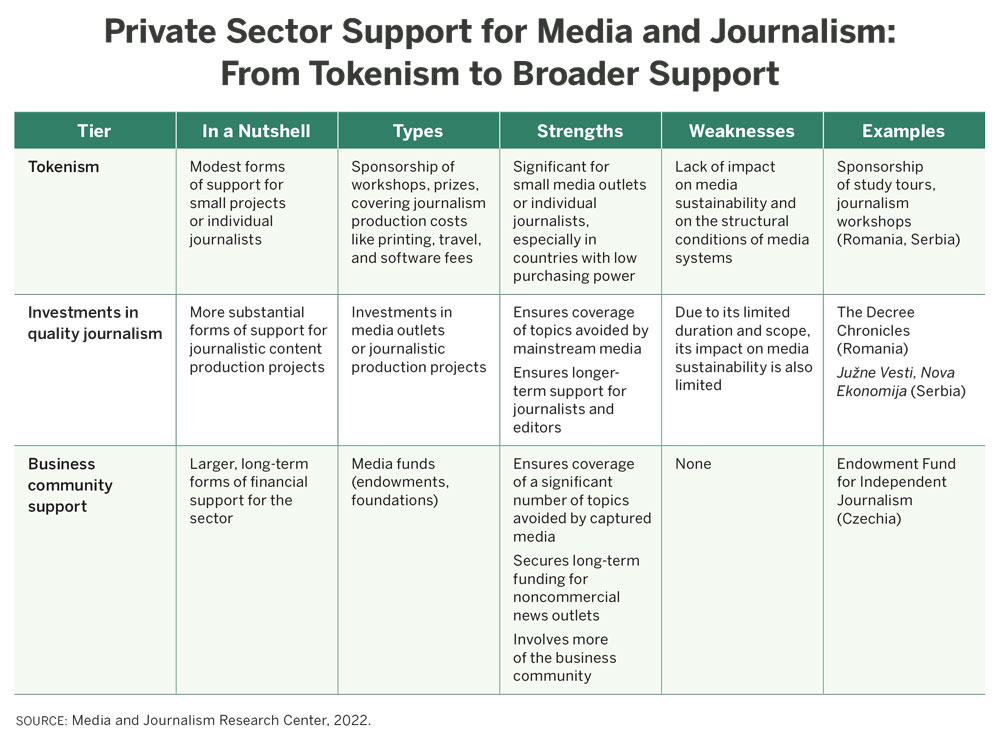

For these reasons, companies operating in such contexts adjust by either playing into the government’s hands or staying under the radar. In Czechia, Romania, and Serbia, there are business leaders and companies that are dedicated to supporting information integrity in their countries. Some of them sponsor trustworthy journalism through philanthropy, while others direct some of their ad budgets to independent, public interest journalism projects and outlets. However, most of them are providing modest forms of charitable support that benefit a small group of journalists or reporting on specific topics. A rare few are exploring broader sector-level approaches that could have a longer-term and more-significant impact. The research aimed to map such initiatives with a view to identifying avenues for private sector investment in countering disinformation and supporting independent journalism, the incentives driving such engagement, and the barriers limiting it.

What Works and What Doesn’t, and Why

Advertising remains the main form of spending by private sector companies in the media.28 Private businesses allocate advertising budgets according to an internal marketing strategy that includes rules on identifying the right news outlets and the returns expected. The decision-making process to identify where corporations spend their marketing budgets is driven exclusively by commercial purposes, and companies choose news outlets based on the reach and demographics of their audiences.29 Usually, editorial independence and journalism quality are not considerations in this process, nor is the rationale to support media freedom and independence. Some companies do, in fact, choose advertising placements to channel cash to the media outlets they want to support for their journalistic independence, according to corporate representatives interviewed for this project. Yet, such examples are rare as companies fear that funding critical media outlets could trigger unwanted consequences. When it does happen, much discretion is involved, making such cases almost impossible to document.

Research into such initiatives in Romania, Serbia, and Czechia reveals several key insights about private sector engagement in the information space, and the norms and incentives that constrain wider participation of the business community in supporting high-quality journalism. First, investment in independent media from private sector actors tends to follow three tiers of support. The bottom tier represents “tokenistic” support—modest levels of financing, usually in the form of awards targeted to specific events or individuals. The middle tier encompasses larger investments that sponsor journalistic content production on specific themes. And the top tier represents funding that is allocated at a wider sectoral level, where businesses mobilize to support the journalistic field in a more substantial way for a longer period.

Second, in the three countries studied, private actors mainly fund content production, largely through philanthropy, and professionalization, primarily in the form of technical assistance, such as sponsoring training workshops. Private companies have been slow to support other types of organizations working on combating disinformation, such as fact-checkers, or more robust forms of support, such as loans or investment capital.

Finally, the research captured an emerging debate among media experts and practitioners about the need to revamp the advertising spending architecture, including through a critical analysis of the incentive structures, to gin up support for independent media outlets through commercial channels, which remain the industry’s key source of income.

Support for Content Production

Support for content production is an important form of private business engagement with independent journalism. In highly captured media environments, where large parts of the private sector are known to be associated with or controlled by the government, ethical companies tend to be reluctant to sponsor journalistic content, which can be highly mistrusted. Moreover, in such places, private companies that are willing to fund independent media avoid being affiliated in any way with independent media outlets, which are usually highly critical of authorities. This allows them to avoid government attacks, direct or indirect, that could be bad for business, such as restrictive or punitive regulatory measures or barriers to participation in public tenders.

Despite these challenges, there are some examples, albeit limited, in the countries of focus where support for content production has led to prominent journalism initiatives. This form of engagement is usually topic driven, where companies choose to work with a media outlet to produce content on a topic of interest and importance. In some cases, the interest is spurred by a business leader’s personal experience. For example, in Romania, The Decree Chronicles30 (Jurnalul Decretului) is a journalistic project that documented stories about victims of abortion bans. The project was spawned by Mihai Matei, a Romanian information technology (IT) entrepreneur. Matei was deeply concerned by the issue because of his mother, who faced substantial hurdles in accessing a safe abortion during the communist regime, when abortion was punishable with prison time. His passion for the issue was based on this experience, and he invested in an initiative aimed at producing journalism documenting such cases and their impact on women and society. By hiring a Bucharest-based nongovernmental organization (NGO) and a team of journalists from a local news outfit, The Decree Chronicles published 14 pieces of long-form multimedia content by its completion in 2021.31

In other cases, support for journalistic production was part of brand building, where the topic matches the values of the company or what the company believes is valued by its customer base. For example, the Romanian Development Bank (Banca Română pentru Dezvoltare, BRD), which is run by the French-owned Société Générale Group, launched a micro-publishing hub consisting of three niche publications, one dedicated to youth culture (Scena932), one to education (Școala933), and one to science and technology (Mindcraft Stories34), to advance the bank’s development strategy. In BRD’s view, culture, education, and technology, the foci of its newly established publications, are key development pillars. For the bank, the launch of this publishing initiative was seen as a form of investing the bank’s brand into publications that the company considers to be important for society, rather than as a corporate social responsibility project.

In other cases, support for journalistic production was part of brand building, where the topic matches the values of the company or what the company believes is valued by its customer base. For example, the Romanian Development Bank (Banca Română pentru Dezvoltare, BRD), which is run by the French-owned Société Générale Group, launched a micro-publishing hub consisting of three niche publications, one dedicated to youth culture (Scena932), one to education (Școala933), and one to science and technology (Mindcraft Stories34), to advance the bank’s development strategy. In BRD’s view, culture, education, and technology, the foci of its newly established publications, are key development pillars. For the bank, the launch of this publishing initiative was seen as a form of investing the bank’s brand into publications that the company considers to be important for society, rather than as a corporate social responsibility project.

There are also examples of private sector support for news content production that are not topic driven and aim to fill a void of independent journalism. Južne Vesti (Southern News) is a Serbian news portal founded by Simplicity, an IT company, in 2010 as a response to the lack of a serious source of local news in the city of Niš. Simplicity almost entirely covers the portal’s costs, using cash from its profit-making business. Similarly, Business Info Group, a privately owned company specializing in public relations, set up the online portal Nova Ekonomija (New Economy) as a response to the scarcity of independent reporting in Serbia.

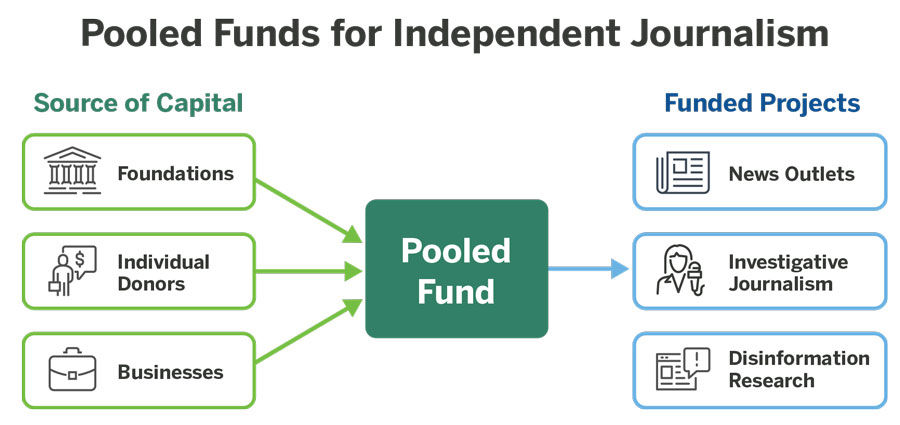

These forms of support can be powerful. They are obviously beneficial for the recipients of funds, and can provide a lifeline for independent media outlets and the journalists running them. They also raise public attention to issues that other media outlets are not covering. However, there are significant limitations. These relationships often provide short-term funding but contribute very little to the long-term sustainability of a news outlet or the broader independent media sector. Second, such projects, especially those that are topic-led, are typically very limited in scope, covering only small niche issues and audiences. Finally, they are unilateral investments made by one businessperson or one company, lacking the traction and impact that a sector-wide initiative would have. The one-sided nature of these investments can also make the news outlet adherent to the views of business actor, which can compromise true editorial independence. These shortcomings can be solved when more businesses join forces to create mechanisms that provide coordinated, robust, and holistic financial support for the independent journalism sector, such as pooled funds.

Pooled Funds

The research identified one promising example of a pooled fund created to support independent journalism—the Endowment Fund for Independent Journalism (NFNŽ) in Czechia. Established in 2016 by 12 businessmen who were all part of a local business club, the NFNŽ emerged as a reaction to the negative impact that oligarchization of the Czech media had begun to exert on the country’s democracy, a common concern of all its founders. The declared goal of the endowment’s founders is to maintain media pluralism and independence in Czechia, which they view as a key condition for meaningful political deliberation.35

The endowment has played a key role both in the philanthropic and journalistic communities in Czechia. A set of internal governance mechanisms ensures transparency of the fund’s actions and accountability of its decisions. As a result of the rigorous procedures, the NFNŽ has attracted financial contributions from around 200 small business donors. The endowment has played a central role in strengthening the health of the local journalistic culture by financing 110 journalistic initiatives to date that received a combined CZK 31 million ($1.4 million).36 Its projects aim to improve the work of various media outlets, such as the launch of a podcast section by Deník N.37 The fund also promotes independent journalism in the country. Since 2018, the endowment has organized the Journalist Forum, an annual event that has become the go-to networking venue for many of the country’s journalists. The endowment also raises important media-related topics to the public. For example, in cooperation with a local activist organization, the NFNŽ has been active in raising awareness of the politicization of the councils that govern Czech public media.

The endowment has played a key role both in the philanthropic and journalistic communities in Czechia. A set of internal governance mechanisms ensures transparency of the fund’s actions and accountability of its decisions. As a result of the rigorous procedures, the NFNŽ has attracted financial contributions from around 200 small business donors. The endowment has played a central role in strengthening the health of the local journalistic culture by financing 110 journalistic initiatives to date that received a combined CZK 31 million ($1.4 million).36 Its projects aim to improve the work of various media outlets, such as the launch of a podcast section by Deník N.37 The fund also promotes independent journalism in the country. Since 2018, the endowment has organized the Journalist Forum, an annual event that has become the go-to networking venue for many of the country’s journalists. The endowment also raises important media-related topics to the public. For example, in cooperation with a local activist organization, the NFNŽ has been active in raising awareness of the politicization of the councils that govern Czech public media.

The NFNŽ has proven to be an effective mechanism channeling locally sourced financial support from corporations and business leaders to independent journalism. Its multilayered governance system, which involves independent experts and journalists in selecting and approving grants, has secured the fund’s reputation in the country’s media field. The funding structure, which allows any type of funder to contribute finances to the endowment, enables both small and large contributors to participate, while ensuring donors’ anonymity. This has functioned well, insulating both donors and journalists from pressure. Unlike larger foreign donors that have complicated and time-consuming application procedures, the NFNŽ has simplified the bureaucracy surrounding applications to allow as many submissions as possible. The fund invites applications from media outlets or groups of journalists for direct financial support for any journalistic initiative. Its expert staff of experienced journalists commission research and use their knowledge of the Czech media industry to identify good projects that need funding.

The local journalism community has critiqued the NFNŽ for a lack of strategic alignment between the fund’s grants and the financing decisions of individual companies. For instance, some journalists claim that companies stopped financing them directly because they contribute to the fund, highlighting a lack of strategic coordination on the part of private companies that support it. Despite this, the journalistic community in Czechia and international observers are overwhelmingly positive about the NFNŽ, considering it a powerful mechanism that helps media outlets and journalists achieve greater financial viability while avoiding capture by business and political interests.

However, not all countries would be able to implement a similar pooled fund approach. A vibrant civil society and a culture of philanthropy are required for such a facility to effectively support independent journalism. Czechia has both. No other similar, currently operational models were identified in the countries of study.

ASMEDI in Serbia is another pooled funding mechanism, though quite distinct from the NFNŽ in its form and structure. ASMEDI is an association of independent media outlets that provides funding for journalistic projects by pooling money generated through membership fees collected from its 37 members. Members include media companies such as publisher Ringier Axel Springer and the Belgrade-focused weekly NIN,38 and private companies, such as Banca Intesa and the advertising behemoth I&F McCann Group, which contribute funds as associate members. While ASMEDI is a joint mechanism set up and run by media businesses to attract funding from private companies, it has nonetheless become one of the few channels available to local businesses in Serbia that want to support the independent media sector. Its impact has been limited, and it has struggled to continue securing donations from members as a result of COVID-19’s detrimental effect on local businesses.

Sponsorship and Support for Professional Development

Private companies use sponsorship to support the professional development of journalists; yet, while this form of support can boost brand exposure for a company, it is less widespread than expected. Moreover, support for training and formal education for journalists, and for civil society associations supporting the professionalization of the sector, is particularly hard to map as much of it is not documented.

Only two awards consisting of cash prizes for journalists were identified in the three countries, with only one that is organized with financial support from a private company—an American drink manufacturer. Although such prizes are generally important for journalists as they add to their prestige, the prizes’ general impact on the media sector remains limited. Journalists prefer financial support for professional development, as most would be unable to afford paying for such training. Programs sponsored by private companies targeting journalism students to intern in media outlets, or specialized investigative journalism workshops, seminars, and study tours, have been found in Serbia and Romania.

Generally, sponsorship and support for journalists’ professional development has limited impact. It is piecemeal and erratic. Companies award sponsorship for professional development based on their finances in a given year and their relationships with local media. As such, sponsorships have limited, if any, impact on the overall financial situation or quality of the media. Another limitation of this form of support is that it can affect the editorial independence of the media outlets accepting it. Even when editorial independence is not compromised, the public is likely to perceive such support as a way of undermining the integrity of a media outlet or journalist who accepts it. For instance, a mining company operating in Romania sponsored a study tour for 14 Romanian journalists to travel to New Zealand. The tour was met with harsh public criticism, even though there was no hard evidence that the company was using the trip to gain favorable reporting about its projects.

Support for Fact-Checking Initiatives

There are few to no examples of private enterprises supporting initiatives aimed at countering disinformation in the countries covered by this study. The primary reason for this lack of engagement by the private sector has to do with an overall absence of awareness of the risk that disinformation poses to companies’ wellbeing. Although more studies are needed to fill the gap in researching the impact of disinformation on private corporations, there are several existing studies concluding that misleading information can have a profound effect on business.39 Disinformation campaigns, for instance, negatively impact the business and financial industries, among other sectors.40 A key purpose of disinformation in the business sector is to tarnish the reputation and brand of a targeted company through baseless criticism or by associating businesses with negative trends or actions, such as breaking the law, engaging in corruption, or hurting the environment.41

Only when concern about disinformation becomes part of the main public narrative as a result of its visibility in the news or other public fora are companies likely to pay attention. Yet, even then, they rarely provide funding for civil society organizations that work on fighting disinformation. They engage with these groups only when they see palpable benefits for the company, such as accessing data and information about sources of disinformation or advisory services about how to handle related public relations crises.

For example, in Czechia, NELEŽ (meaning “don’t lie” in Czech), is a fact-checking NGO that has established partnerships with more than 200 organizations made up mostly of private companies including tech firms and online ad providers. It has experienced declining interest in its work from partners that have not received concrete services from the organization. NELEŽ was launched by a team of public relations experts in 2020 with financial support from mobile service provider T-Mobile with a mission to raise awareness about the harm that disinformation can inflict on a company’s brand or operations. At that time, telecom providers were struggling to fix problems that arose during the rollout of fifth-generation (5G) technology in the Czech market because of a disinformation campaign linking the electromagnetic fields from 5G networks to various health issues, including the COVID-19 pandemic.42 Websites peddling disinformation were able to take advantage of the general public’s lack of awareness of how the technology works to churn out content pushing alarmist conspiracy theories. “Of course, it’s about attention, because it means clicks and thus more profit from ads,” said Petr Nutil, a Czech journalist who specializes in disinformation, in an interview with a Czech news outlet. “As always, fear attracts attention and generates money.”43

For example, in Czechia, NELEŽ (meaning “don’t lie” in Czech), is a fact-checking NGO that has established partnerships with more than 200 organizations made up mostly of private companies including tech firms and online ad providers. It has experienced declining interest in its work from partners that have not received concrete services from the organization. NELEŽ was launched by a team of public relations experts in 2020 with financial support from mobile service provider T-Mobile with a mission to raise awareness about the harm that disinformation can inflict on a company’s brand or operations. At that time, telecom providers were struggling to fix problems that arose during the rollout of fifth-generation (5G) technology in the Czech market because of a disinformation campaign linking the electromagnetic fields from 5G networks to various health issues, including the COVID-19 pandemic.42 Websites peddling disinformation were able to take advantage of the general public’s lack of awareness of how the technology works to churn out content pushing alarmist conspiracy theories. “Of course, it’s about attention, because it means clicks and thus more profit from ads,” said Petr Nutil, a Czech journalist who specializes in disinformation, in an interview with a Czech news outlet. “As always, fear attracts attention and generates money.”43

As most of the websites spreading disinformation and conspiracy theories in Czechia are funded through advertising revenues (in 2020, the largest websites disseminating disinformation in Czechia earned up to CZK 190,000 [$8,600] a month from advertising sales44), NELEŽ aims to identify such cases and advise private companies to withdraw their ads from those sites.45

Within a year of its founding, NELEŽ established partnerships with organizations committed to following its recommendations on where not to advertise, and the companies rewarded the service with funding or in-kind support.

Private sector support for fact-checking organizations or projects remains marginal. In the countries of focus, most of them receive funding through consultancy fees or grants from philanthropic organizations. For example, the most renowned fact-checking group in Czechia, Demagog.cz, receives some support from private companies, yet its core funding comes from consultancy contracts. In Serbia, a country flooded by disinformation from foreign sources and dominated by propaganda-focused, government-funded media outlets, the fact-checking market is still in its infancy, which is arguably a reason why private businesses have not shown interest in the topic. The most prominent fact-checking organization in the country, Istinomer, which operates across the Balkan region, funds itself exclusively through consultancy contracts and grants from foreign donors.

Yet, despite the lack of appetite among private businesses to fund fact-checking work, growing disinformation and foreign influence in recent years appear to be prompting some companies to take heed. In Czechia, where such influence has been on the rise, T-Mobile46 and O247 have begun investing in media literacy initiatives as part of their philanthropic activities, a trend seen among telcos operating across Central and Eastern Europe.

Advertising Revenue

Although commercial advertising remains a key source of funding for the media industry, private companies in the countries studied do not widely use this channel to support independent journalism. A primary reason for this has to do with the dominant commercial logic that guides the advertising market. Private businesses engage solely with media buyers that possess solid audience data to identify the media outfits that can bring them the size and type of consumers they need for their products and services. It is important to note that independent journalism is not fully excluded from this market: Independent media outlets are also included in the advertisers’ spending plans, depending on the types of audiences they serve.48 Yet, under competition-related pressures, private companies do not earmark ad funds to channel specifically to independent journalism, preferring instead to stick to the commercial logic that defines their spending strategies.

An unhealthy ad market can also pose significant limitations to private businesses’ engagement with media and journalism initiatives, especially during periods of economic recession. For instance, the decline of the Romanian ad market, which never fully recovered after a massive economic crisis–induced slump in 2009, has been forcing media outlets to increasingly resort to unethical negotiations to land ad contracts, including placing editorial content in exchange for cash. Such practices encourage companies to invest in content-related deals instead of supporting media outlets where they do not have any influence over the editorial line.

Above all, the primary obstacle to greater and more systematic financing of independent journalism through the advertising industry is the existing model of ad revenue distribution, which is not conducive to promoting high-quality reporting. A seasoned media analyst from Romania, Dragoș Stanca, says that the system of ad distribution in the country “sucks the marrow out of the very media system.”49 Much of the ad spend in Romania, as elsewhere, is allocated based on quantitative criteria, hence going to large tech platforms, such as Google and Facebook. This logic creates a self-replicating consumption pattern: the more people who watch untrustworthy or sensationalist content, the more ad money that is directed to it, encouraging creators to focus solely on producing that type of content. “It is difficult, we are fighting against human nature,” Stanca said, warning that people will always be attracted by easy-to-grasp content that confirms their biases rather than serious, critical news. We should not aim to change that, Stanca warned. Instead, a solution would be to create an “ethical advertising” mechanism by rejigging the current ad spend distribution system to divert part of the ad expenditure to quality journalism. Yet, rewriting the logic of private sector ad spend in this way would require sustained effort and solid incentives to secure the buy-in of the industry.

Private Sector Support for Independent Journalism: Limitations and Barriers

Systemic Problems

Government interference in the media is by far the biggest hurdle to private companies’ engagement with journalistic initiatives. The more captured a media environment becomes, the less receptive private businesses are to engage with independent news outlets. Corporations in these settings are fearful of clashing with the interests of media outlets controlled by authorities and of being connected with media players known to be critical of the government. Excessive government control in the media is a particularly strong deterrent for private sector investments in quality journalism and encourages private companies to limit themselves to small, tokenistic, and often anonymous forms of support. In countries where the government, in addition to controlling the media field, also steps up its attacks on independent media, private companies steer away from engaging with critical outlets as a way to avoid similar attacks.

In Serbia, for example, independent media outlets and organizations associated with them commonly face unannounced tax audits as a punitive measure, which can badly disrupt the operation of a media house and last several months. An even more distressing tactic to harass the media is when government bodies blacklist journalists under accusations of money laundering or aiding terrorists, which also deters private companies from associating themselves with media outlets employing those journalists. Even if such allegations are eventually proven baseless, they have dire consequences for the outlets run by blacklisted people. The situation is even worse in small towns, where businesspeople and companies refrain from funding independent media altogether to avoid being harassed by the local government.

Among the three country cases analyzed for this report, Serbia stands out in terms of its high level of government control of the media, which has been cemented through a botched, lengthy, corruption-laden privatization process for the formerly state-owned media outlets in the country, leaving little room for genuinely independent journalism. During this process, a slew of media outlets were propped up by private investors with funds from the government, a strategy aimed at preserving the government’s control of those media.50

In Romania, collusion among media, politics, and business, rather than state control of the media, presents an insurmountable obstacle to private businesses supporting independent media and information. Collusion can take many forms, including direct pressure by media owners on journalists to influence their reporting, but also indirect interventions in journalists’ work to ensure the “protection” of various politicians or government officials supportive of, supported by, or close to the media owners. A similar situation can be seen in the private media sector in Serbia, which is excessively concentrated in the hands of a few influential people, often linked with powerful politicians, usually from the largest political party in Serbia,51 President Aleksandar Vučić’s Serbian Progressive Party (Srpska napredna stranka, SNS).

In contexts characterized by complicity among media outlets, political actors, and the business sector, all forms of private sector engagement with independent journalism face insurmountable challenges. Investment in journalism production happens, yet private businesses tend to support outlets close to them or to their political allies. Tokenistic support is therefore the easiest approach to funding independent media, but this can swiftly turn into yet another mechanism of control (for example, by paying for journalists to take trips or participate in training) or shed a bad light on media outlets benefiting from it (for example, when a journalistic award is sponsored by a company known to be associated with certain political groups).

Lack of Experimentation

A major barrier to private sector support for journalism is related to the scarcity of investment channels and mechanisms. Countries where the media sector has experimented with a larger variety of funding models52 offer more opportunities for donors to support journalism. In contrast, countries with less innovative approaches to media business models, and less developed economies, present limited opportunities for support.

For instance, crowdfunding, which has been tested for more than a decade in many parts of the world,53 has developed at a snail’s pace in Serbia for two reasons. First, there are few legal provisions for copyright that are suitable for the digital era, which leads to a thriving copy-paste journalism culture where articles are shared across most media portals, discouraging financial donations. Second, there is an enduring public perception that crowdfunding is a form of charity that is totally inappropriate for the media sector. This perception has caused some outlets, like Nova Ekonomija, to avoid crowdfunding altogether to avoid cannibalizing its fundraising efforts. (See more in Private Sector Support for Independent Journalism: Opportunities)

Sectoral Problems

A major factor that limits private sector support for journalism is a lack of effective communication and shared knowledge of the operating logic between the two sectors. The business community is not proactive in looking for media or journalistic projects to invest in, sticking instead to their internal marketing strategies, anchored by the annual cycle of advertising in media outlets. Private businesses do not understand how journalism works, and journalists do not see much value in helping companies understand how they work. To some journalists, especially in environments with highly corrupt media, engaging with the private sector at all could be considered unethical, so they avoid engagement to ensure the integrity of their reporting.

Businesses interested in supporting independent journalism, on the other hand, do not have a clear mechanism for identifying outlets or projects worth supporting. As a result, when cooperation does happen, it is up to individual business leaders or staff working in companies to come up with ideas for news initiatives, and then partner with journalists to implement them. Matei, the entrepreneur who financed The Decree Chronicles initiative in Romania, started the project by posting a call on his Facebook page for stories on the topic he chose for the project. He then reached out to local journalists to design and launch the initiative. Improved communication between the two sectors would open new potential avenues for engagement and offer private businesses more options for support.

As a response to this need, several media development organizations have created tools54 for private businesses to identify trustworthy media outlets or projects worth supporting. However, in Central and Eastern Europe, there is currently no single approach in place to collect and disseminate data on the trustworthiness of different news outlets that businesses could use to guide their investment decisions.

Private Sector Support for Independent Journalism: Opportunities

The barriers to enlisting greater private sector support for independent media are daunting, especially in highly captured business and media environments. But several examples identified in this research hold promise, and could potentially be replicated in other contexts.

The pooled resource model—such as the Czech endowment—is a resilient and effective form of support because it insulates private companies from government attacks and provides more systemic and enduring support for the independent media sector. This approach allows companies to contribute their funds anonymously and to deploy capital in a strategic and coherent manner, rather than making one-off donations to individual media outlets or projects. Compared with funding from foreign donors or philanthropists, which can create stigma for the media outlets that accept it, a pooled local resource model with funding disbursed by independent and neutral experts can be more context-driven and less vulnerable to criticism of foreign control. However, as the Czech example shows, such locally sourced endowments work only in countries with a healthy civil society and strong philanthropic culture where many business actors openly show their ideological commitments to democracy. Moreover, creating a journalism endowment takes significant effort, including sustained advocacy and networking, and requires solid systems or tools to identify credible outlets that are worth investing in.

Harnessing the appetite of private companies to support journalistic and fact-checking initiatives is another important opportunity. Even in the most state-controlled markets, where the majority of media outlets are in the hands of the government or politically affiliated oligarchs, some corporate actors recognize the critical importance of a healthy infosphere. Many of these businesspeople, concerned about the consequences that a captured media environment and high levels of disinformation can have on their businesses and on broader economic conditions, are interested in establishing neutral financial vehicles, such as funds or endowments, that enable them to fund independent media. Private businesses are also constantly looking for data that can serve their businesses. As media outlets can provide such data, that provides a potential win-win opportunity.

Experimenting with new forms of funding and fundraising in the media sector presents another important opportunity, particularly in Central and Eastern Europe, where adoption of such models has been slow. Company representatives indicate that crowdfunding in various forms can encourage and inspire businesses to support independent journalism, as it offers anonymity, is easy to scale up or down, and requires relatively low maintenance costs and little bureaucracy, which can be an important incentive.

Finally, the potential of remodeling the advertising infrastructure to divert part of the ad spending toward independent journalism needs to be explored. The advertising industry’s current logic largely promotes poor-quality content and audience quantity over high-quality, trustworthy journalism. Advertising associations and networks can be incentivized to create a roadmap for establishing a system of ethical advertising to support independent journalism. Stanca, the Romanian advertising expert, explains that advertisers would like to have more control over selecting the targets of their spending, which they currently lack because ads are distributed automatically through integrated online systems such as Google Display Network. “I talked to people in the business sector [in Romania], smart and competent people, and they had no idea how the advertising market functions. They had no idea that they are actually funding the very kind of content they, as media consumers, complain about,” Stanca said.55 He envisions a system allowing advertisers to voluntarily divert a small proportion of their marketing budgets, up to 3 percent, for example, to “social content that serves the greater good”—ad lingo for public interest journalism.

For such a system to work, private businesses need solid incentives. Giving them more control over their ad placements is one motivator. Second, they need to better understand the media outlets or initiatives that would benefit from ethical advertising expenditure, which requires a consistent and transparent mechanism for assessing and documenting the registration, performance, and professionalism of news outlets. As the global debate around the need to revamp the ad spending architecture heats up, some promising approaches provide important insights. Ads for News, an initiative of a nonprofit coalition of industry leaders and experts, is working toward providing private companies with a “free, global inclusion list of trusted local news media.”56 Another example is NewsGuard, a journalism and tech company founded in 2018 by two American media experts that rates the credibility of news portals using a set of journalistic criteria. Through one of its services, BrandGuard, the company works with advertisers to help them create curated lists of news outlets to include or exclude from ad placement. Other ad checking services in place include the Global Disinformation Index, a digital platform providing independent data that can be used by business leaders to combat disinformation,57 and Check My Ads, an independent watchdog organization working to make the advertising marketplace more transparent.58

Such initiatives are a significant step forward, yet, as most of the ad spending decisions are made at national market levels, depositories of media knowledge to serve interested advertisers need to be localized. An innovative initiative is PressHub Market in Romania, a project launched in 2019 by Freedom House and PressHub, a network of 27 Romanian media outlets, to support local and independent media in the country.59 Over 20 media outlets, mostly local, joined PressHub Market, which is organized as an online shop featuring editorial products offered by the media outlets to potential advertisers.60 Another one is Konšpirátori, an initiative established by key publishers and marketing experts in Slovakia to create a database of problematic websites (i.e., those disseminating mis- and disinformation) that advertisers should avoid.61

Conclusions: Upgrading to More Meaningful Investment

At a time when the space for independent journalism is rapidly shrinking, private businesses can play a much bigger role in supporting a healthy news media environment. Yet, the engagement of this sector remains modest. There are very few examples where the business community is leaning in to help solve the broader sustainability challenges the media sector is facing. Nonetheless, the cases identified have implications and can provide inspiration for strengthening the relationship between the private sector and independent media.

In supporting independent journalism, private businesses swing from tokenism to investments in quality journalism, yet very rarely do they venture into mobilizing the business community to support the whole journalistic sector in a way that could enable the proliferation of quality journalism and enhance media sustainability. This is often due to the difficult environments in which businesses and independent media operate in developing countries, new democracies, and democracies under threat. Modest sponsorship of events or training for journalists is an easy form of involvement that does not jeopardize businesses’ relationships with authorities or their allies. From time to time, some of them “upgrade” to investing in journalistic projects, a decision often triggered by the relevance of a project to the company’s values or by the personal interests of a company’s owners or managers.

Very rarely, businesses climb to the third tier of engagement, galvanizing the private sector to support the journalistic sector in a strategic and systematic way. As the Endowment Fund for Independent Journalism (NFNŽ) demonstrates, such mechanisms of support need a strong local philanthropic culture and a vibrant civil society, which Czechia has, to be successful. But despite these contextual limitations, the example of the NFNŽ, due to its structure and operation and the industry’s buy-in, provides rich inspiration for the business community to move from tokenistic, small support to a more sectoral, impact-driven approach. Even so, when efforts are made to rally the business community around larger, long-term mechanisms of support, it cannot be taken for granted that corporations value independent journalism. The NFNŽ is an exceptional case because the underlying motivation for it was related to supporting democracy and countering extreme oligarchization of the media.

Yet, in most cases, business leaders are keen to see concrete benefits for their companies when they support a project. Understanding these motivations and finding modes of incentivization are crucial in attracting private sector support. As media companies are grappling with dwindling revenues, attacks from the government, and the public’s reluctance to pay for journalistic content, the private sector can play a major role in supporting an independent information ecosystem. So far, the private sector’s contribution to protecting independent journalism has been strikingly modest. More sustained, long-term, strategic engagement through new, more advanced forms of support is needed. “Romanian companies should grow a spine and invest in media projects on sensitive issues that are avoided by mainstream media,” said Matei, the Romanian investor.62 For many companies, that is an existential decision.

Looking Ahead: Recommendations for a Stronger Private Sector–Journalism Relationship

There is no universal recipe for private businesses willing to support initiatives that contribute to a healthy infosphere. The local context, including the economic conditions, cultural norms, level of technological advancement, political circumstances, and particularities of the private sector, greatly influence the relationship between private companies and the media. Businesses and media have always interacted in a variety of ways, but examples of business leaders and groups championing initiatives to support independent journalism are rare. Moreover, the ones that do exist typically lack long-term vision and most fail to make a significant impact on the broader information space. To help galvanize greater engagement, and investment, of the business community in supporting information integrity, concrete steps in three areas need to be made.

Research

Evidence of the impact of private business support for independent journalism and of the benefits that such support brings to private companies remains scarce. Donor organizations and industry groups should commission research into the following:

– The impact of existing initiatives of private businesses to support independent journalism (e.g., the impact of the NFNŽ on media sustainability in Czechia)

– The benefits that private businesses can gain by supporting independent journalism (e.g., mapping the size and demographics of the audiences consuming independent journalism, or the social impact of independent journalism projects on the reputation of companies that offer support)

– The harm inflicted by disinformation on companies’ performance and prestige (e.g., negative consequences of disinformation on brand reputation, sales, and public perception)

Advocacy

Private sector actors have limited awareness of and exposure to issues related to the democratic role of independent journalism and the importance of supporting it.

There is a need for greater advocacy at the national, regional, and global levels to raise the following issues:

– The detrimental effect of information disorder on the performance and prestige of companies

– The role of independent media in protecting the information space and mitigating the harmful effects of disinformation and propaganda, and the structural challenges the sector faces

Business Engagement

Private business engagement with the journalism sector is isolated and localized. Such engagement is often limited to one-off interventions or time-bound projects. Much of this engagement in different countries and regions remains undocumented. Donor organizations and NGOs working with private businesses should focus on promoting existing good practices and facilitating exchanges aimed at developing new mechanisms of support. These efforts could involve the following:

– Identify business leaders, corporations, and private sector networks with a genuine commitment to democratic principles

– Support successful projects (e.g., the NFNŽ) to seed their ideas with their peers in other countries

– Work with media experts to design impactful income-generating and trust rating tools targeted to the private sector (e.g., PressHub Market in Romania, Newsguard, Ads for News, or Konšpirátori in Slovakia)

– Prepare a journalism support toolkit for ethical businesses to serve as a guide for private businesses interested in supporting independent journalism

– Develop more extensive guidelines on how information space ethics can fit into environmental, social, and corporate governance/corporate sustainability frameworks

– Establish a global forum of media experts consisting of thinkers and practitioners with experience in media and advertising to design a prototype of an ethical advertising distribution system focused on promoting independent journalistic content that could be replicated in different contexts

This research highlights existing examples of the private sector rising to the challenge of information disorder in several countries, and green shoots likely exist elsewhere. Media development actors can look to these locally driven efforts as a foundation for building stronger solidarity with the private sector in a shared vision for protecting information integrity. The private sector’s best efforts to countering mis- and disinformation and supporting independent journalism should be empowered to continue growing and similar efforts should be seeded elsewhere. Where such initiatives are lacking, existing tokenistic efforts should be expanded into more meaningful partnerships between business and independent media.

Improving the dire state of independent media and stymieing the rising tide of disinformation globally requires new approaches, partnerships, and financial resources. There is good reason to believe that this is possible. But unlocking this catalytic potential requires more concentrated collaboration between the business community and the media sector, and new mechanisms to draw in private capital.

Methodology

The research project “Investing in Facts: How the Business Community Can Support a Healthy Infosphere” was carried out between November 2021 and June 2022 by a team of eight researchers under the leadership of Marius Dragomir, director of the Media and Journalism Research Center.

The project was based on data and information collected through secondary research and 57 interviews.

The main research goal was to identify ethical models of business engagement that support independent media, journalistic initiatives, and groups working on combating disinformation. The secondary goal of the project was to analyze the main barriers to and opportunities for private business engagement with such initiatives. The research covered only independent initiatives (i.e., those without links to the government or other groups of interests) that engage with privately owned companies.

The project was conducted in two phases:

Phase 1: Global scanning (November 2021-January 2022)

A team of six researchers conducted secondary research and interviews in 61 countries to identify examples of private business engagement with journalism and fact-checking initiatives. The research covered articles in the media and a study of corporate policies and documents, including reports focused on environmental, social, and corporate governance and corporate social responsibility; academic papers; and NGO reports. A total of 36 interviews with experts in business practices and media, media development specialists, and journalists were conducted. The countries covered by the research were selected based on a set of criteria that included geographic diversity, type of political and media system, democratic record, and economic and technological development. They included 16 countries in Latin America, 12 countries in Eurasia, 11 countries in Central and Eastern Europe, 10 countries in the Middle East/North Africa region, eight countries in sub-Saharan Africa, and four countries in Asia.

The research in Phase 1 helped the team gain a better understanding of the relationship between private companies and media outlets/fact-checking groups.

Phase 2: Country case studies (January 2022-May 2022)

Based on the findings from the project’s first phase, Czechia, Romania, and Serbia were selected as in-depth country case studies. Using the same methodological mix as in the first phase (secondary research and interviews), researchers in the three countries collected data and information about cases of engagement between private companies and journalistic/fact-checking initiatives.

The research covered articles in the media and a study of corporate policies and documents, including academic papers, NGO reports, and local trade registries. A total of 21 interviews were conducted across the three countries analyzed in this phase.

The country researchers followed a research template made up of a series of research questions and research methods. Their findings were presented in three individual country reports, accessible at the following links: Czechia, Romania, and Serbia.

Acknowledgements

An international team of experts conducted research and interviews for this report: Ioana Avadani, Binod Bhattarai, Luis Miguel Carriedo, Giorgi Jangiani, Nevena Krivokapić, John Masuku, Petar Radosavljev, Jonáš Syrovátka, and Bouziane Zaid.

This report is the result of a joint initiative between the Center for International Media Assistance and the Center for International Private Enterprise.

About the Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE)

The Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE) is a global organization that works to strengthen democracy and build competitive markets in many of the world’s most challenging environments. Working alongside local partners and tomorrow’s leaders, CIPE advances the voice of business in policy making, promotes opportunity, and develops resilient and inclusive economies. CIPE is a core institute of the National Endowment for Democracy and a non-profit affiliate of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. Visit cipe.org, LinkedIn, Facebook, or Twitter to learn more about CIPE.

Footnotes

- For more information on media capture, see Anya Schiffrin, ed., In the Service of Power: Media Capture and the Threat to Democracy (Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance, 2017), https://www.cima.ned.org/resource/service-power-media-capture-threat-democracy/.

- Mary Myers, Defending Independent Media: A Comprehensive Analysis of Aid Flows (2010–2019) (Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance, forthcoming).

- “Why We Were Established,” NFNŽ, n.d., https://www.nfnz.cz/o-fondu/proc-jsme-vznikli/, accessed July 15, 2022.

- Marius Dragomir, Media Influence Matrix: Czech Republic (Budapest: Center for Media, Data and Society, September 2018), https://cmds.ceu.edu/sites/cmcs.ceu.hu/files/attachment/basicpage/1396/mimfundingczech_2.pdf.

- Lenka Waschková Císařová and Johana Kotišová, “Crumbled Autonomy: Czech Journalists Leaving the Prime Minister’s Newspapers,” European Journal of Communication 37, no. 5 (2022): 529–544, https://doi.org/10.1177/02673231221082242.

- Michal Klíma, Media Capture in the Czech Republic: Lessons Learnt from the Babiš Era and How to Rebuild Defences against Media Capture (Vienna: International Press Institute, 2022), https://ipi.media/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Media-Capture-in-the-czech-Republic.pdf.

- Ivo MinarřÍk, “Když půjdeme cestou Maďarska, skončíme tady, říká šéf Y Softu Muchna” (“If We Go Hungary’s Way, We End There, Says Y Soft’s Boss Muchna”), Svet Chytre, September 4, 2020, https://svetchytre.cz/a/p7ShM/kdyz-pujdeme-cestou-madarska-skoncime-tady-rika-sef-y-softu-muchna.

- Rosario de Mateo, Laura Bergés, and Anna Garnatxe, “Crisis, What Crisis? The Media: Business and Journalism in Times of Crisis,” tripleC 8, no. 2 (2010).

- Jeff Kaye and Stephen Quinn, Funding Journalism in the Digital Age: Business Models, Strategies, Issues and Trends (New York: Peter Lang, 2010), 185 pp.

- Rasmus Kleis Nielsen and David A.L. Levy, “The Changing Business of Journalism and Its Implications for Democracy” in The Changing Business of Journalism and Its Implications for Democracy, eds. Rasmus Kleis Nielsen and David A.L. Levy (Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, 2010), 3–15.

- Elliot King, Free for All: The Internet’s Transformation of Journalism (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2010).

- James R. Compton and Paul Benedetti, “Labour, New Media and the Institutional Restructuring of Journalism,” Journalism Studies 11, no. 4 (2010): 487–499.

- Marius Dragomir, “Control the Money, Control the Media: How Government Uses Funding to Keep Media in Line,” Journalism 19, no. 8 (2017), 1131–1148, https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884917724621.

- Marius Dragomir, Media Capture in Europe (New York: Media Development Investment Fund, 2019), https://www.mdif.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/MDIF-Report-Media-Capture-in-Europe.pdf.

- Jef I. Richards and John H. Murphy II, “Economic Censorship and Free Speech: The Circle of Communication between Advertisers, Media, and Consumers,” Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising 18, no. 1 (1996): 21–34, DOI: 10.1080/10641734.1996.10505037.

- Nic Newman and David A.L. Levy, eds., Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2013 (Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, 2013).

- Adil Nussipov and Marius Dragomir, Media Influence Matrix: Kazakhstan. Funding Journalism (Budapest: Center for Media, Data and Society, June 2019).

- An Ipsos poll carried out in 27 countries worldwide in 2019 found that in most countries, “trust is more often perceived to have decreased over the last five years than to have increased.” (“Trust in the Media,” Ipsos Global Advisor, 2019, https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/publication/documents/2019-08/ipsos_global_advisor_-_trust_in_the_media.pdf); another poll, conducted in 2022 by Gallup, found that Americans’ confidence in newspapers and television news had dived to “all-time low points.” (Megan Brenan, “Media Confidence Ratings at Record Lows,” Gallup, July 18, 2022, https://news.gallup.com/poll/394817/media-confidence-ratings-record-lows.aspx); a separate study from Reuters Institute, an Oxford-based research outfit, found that 38 percent of people tend to avoid news, an increase from 29 percent in 2017 (See Helen Coster, “More People Are Avoiding the News, and Trusting It Less, Report Says,” Reuters, June 15, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/business/media-telecom/more-people-are-avoiding-news-trusting-it-less-report-says-2022-06-14/).

- Defined as websites that peddle false information while purporting to be legitimate sources of news and information.

- Judit Szakács, Trends in the Business of Misinformation in Six Eastern European Countries: An Overview (Budapest: Center for Media, Data and Society, May 2020), https://cmds.ceu.edu/business-misinformation-slovakia-snake-oil-spills-web.

- Dumitrita Holdis, “Monetizing Dacians and the Apocalypse” in The Business of Misinformation research series (Budapest: Center for Media, Data and Society, February 2020).

- Semir Dzebo, “Lying for Profit” in The Business of Misinformation research series (Budapest: Center for Media, Data and Society, August 2019).

- Tristan Bove, “‘There Is a Risk Our Advertising Would Appear Next to the Wrong Messages.’ Companies Are Already Pulling Ads off Twitter because of Hate Speech Concerns,” Fortune, November 9, 2022, https://fortune.com/2022/11/09/twitter-hate-speech-companies-pulling-ads/.

- Kristína Šefčíková, Alena Zikmundová, and Roman Číhalík, Disinformation and Brand Safety: The Approach of the Czech Private Sector (Prague: Prague Securities Study Institute, March 2022), https://www.pssi.cz/download//docs/9646_disinformation-and-brand-safety-en.pdf.

- Robert Brestan, “Miliardář Martin Vohánka: Potřebujeme tu kamiony i nezávislou žurnalistiku” (“We Need the Trucks and Independent Journalism”), Hlidaci pes, July 29, 2019, https://hlidacipes.org/miliardar-martin-vohanka-potrebujeme-tu-kamiony-i-nezavislou-zurnalistiku/.

- Manager of Eastern European telco company, in an interview with the author, March 1, 2022.

- The News Trust Halo: How Advertising in News Benefits Brands (New York: IAB, October 2020), https://www.iab.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/IAB-Research-Report_Value-of-News_102720Final1.pdf.

- Marius Dragomir, State Financial Support for Print Media: Council of Europe Standards and European Practices, (Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe, November 2021), https://rm.coe.int/file-2-marius-report-eng/1680a4d519.

- Based on information obtained through interviews carried out in this project.

- “Home,” The Decree Chronicles, Center for Independent Journalism, 2021, https://decreechronicles.com/.

- Ioana Avadani, It’s All about People: Supporting Journalism in Romania (Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance, March 2023).

- See more at https://www.scena9.ro/, accessed May 9, 2022.

- See more at https://www.scoala9.ro/, accessed May 9, 2022.

- See more at https://mindcraftstories.ro/, accessed May 9, 2022.

- “Why We Were Established,” NFNŽ, n.d., https://www.nfnz.cz/o-fondu/proc-jsme-vznikli/, accessed July 15, 2022.