Key Findings

In July 2018, the government of Uganda implemented a tax on individual users of social media platforms. In the first three months following the introduction of the tax in the country, internet penetration dropped from 47 percent to 35 percent. Given that a significant amount of news circulation now happens via social media and messaging apps, how might this new tax impact the news media ecosystem? The negative effects on news media are less direct and arguably more pernicious than might be expected.

• Internet penetration in Uganda dropped from 47 percent to 35 percent in the first three months after social media tax introduction.

• Journalists noted a significant decline in the level of engagement with readers and sources via social media platforms.

• Traffic to new sites has been only minimally impacted, indicating that sites were not reliant on social media to begin with and/or that many individuals have turned to VPNs to avoid the tax.

Introduction

Does restricting access to social media by taxing individuals actually improve the quality of news and information circulating in a society? Far-fetched as such a proposition may be, policymakers in Uganda are making such a claim.

Does restricting access to social media by taxing individuals actually improve the quality of news and information circulating in a society? Far-fetched as such a proposition may be, policymakers in Uganda are making such a claim.

On May 31, 2018, the Ugandan parliament passed a law that instituted a “social media tax” users would have to pay to access social networking and messaging apps like WhatsApp, Facebook, and Twitter. This new excise duty went into effect on July 1, 2018, and now users of these platforms and other over-the-top (OTT) media services must pay 200 Ugandan shillings (approximately 5 US cents) per day to access these sites. In addition to potentially raising revenue for government outlays, longtime Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni claimed that this tax on individuals would also help the country cope with olugambo, or gossip, online.1 However, freedom of expression advocates immediately condemned the new tax as part of a broader government effort to quell political dissent by stifling people’s ability to express themselves and access news and information.2

While much of the outcry against the social media tax has focused on how it might curtail political speech online, far less attention has been paid to the potential impact on the circulation and production of independent news. Given that worldwide citizens are increasingly accessing news content via social media, this policy also has seemingly direct consequences for what types of news stories citizens are able to access. Moreover, as journalists have started to rely on social networks for reporting, sourcing stories, and engaging with audiences, the implications are broader than just distributing news content. The tax also impacts the ability of journalists to report on topics of public interest and reach sources who use media to communicate.

In Uganda, almost a year after this first-of-its-kind social media tax was implemented, we are beginning to finally see what the actual consequences of such a policy are. It turns out that the negative effects on news media are less direct and arguably more pernicious than you might expect.

The Ugandan case is just the latest example of how governments are trying to assert more influence over social media platforms and the circulation of news. Indeed, right now a handful of other countries in sub-Saharan Africa are also considering enacting similar social media taxes on their citizens. Thus, understanding the impacts of this policy on media development in Uganda serves to highlight the consequences and costs of efforts to regulate the internet in this way.

The Current Media Landscape

To understand the potential impact of the social media tax on news in Uganda, it is first important to review the broader media landscape. Uganda’s media sector was liberalized 3 in 1993, but to date the state still runs key outlets such as the Vision Group, which publishes the country’s highest circulating daily newspapers including New Vision (in English) and Bukedde (in Luganda). The group also publishes the only regional newspapers and owns six radio stations and three television channels. It nonetheless faces competition from privately owned entities including the Daily Monitor and NTV of the Nation Media Group, NBS of the Next Media Group, and hundreds of FM radio stations around the country.

In recent years, there has been a proliferation of independent content creators online who through social media, blogs, independent news sites, and podcasts have bridged a gap between traditional media formats and Ugandan digital media consumers. These platforms have also contributed significantly to traditional media platforms by increasing journalists’ proximity to the source of news stories and plugging them into issues and conversations of interest to the public, as highlighted by social media. More recent movements in civic technology, open data, and other similarly sophisticated applications of internet technology have deepened interest in transparency, accountability, and the character of news content and its dissemination.

The growth in online content was spurred first by the opening up of the telecommunications sector in 2007 4 following which mobile phones became the primary means by which Ugandans access the internet. The total mobile phone subscription rate by the end of June 2017 stood at 23.6 million, 5 representing a tele-density of 57 percent for Uganda’s population of 41.3 million.

Initially, the government took a progressive approach to this growth toward a more connected world. Indeed, the state mirrored widespread interest in the use of the internet as an engagement channel by, for example, developing social media guidelines 6 for ministries, departments, and agencies to support the principles of open government, and seeking “public collaboration in finding solutions to problems.”

However, this evolution has been accompanied by an increasingly vocal citizenry—one that is readily using technology to demand accountability and transparency, and push back against oppression. This has not been as enthusiastically received by the state, which in February 2011 interrupted the flow of communications by blocking SMS messages that included a range of preselected words 7 including “Egypt,” “people power,” and “dictator” ahead of the elections. This was the first documented incident of digital communications being censored during elections in the country.

Five years later, the election in 2016 revealed that the state was willing to go even further in terms of curtailing access to content online. Even though this election was the first in which both the incumbent, Museveni, and opposition leaders aggressively used social media to appeal to younger voters as part of their electioneering campaigns, the state ordered two social media shutdowns in the space of three months 8 to reportedly maintain public order and protect national security. In general, the state’s attitude toward online engagement seems to have taken a negative turn. Since 2013, the government has spoken of introducing a social media monitoring center “to weed out those who use it to damage the government and people’s reputations.”9

The Dawn of Taxation on Social Media Access

The Uganda Communications Commission (UCC), the government regulatory body of the communications sector, first called for regulation of social media platforms in 2016 with the executive director of the authority stating that “self-regulation is not sufficient and additional regulatory tools such as public supervision, legislations or even administrative measures are required.”10 Two years later, in July 2018, the UCC published a notice calling for online content providers including online publishers, news platforms, and radio and television operators to “apply and obtain authorization” for the provision of these services—potentially threatening access to information and free speech.11 The notice also stated that as of April 2, 2018, it would embark on enforcement activities against all non-compliant providers of online data communication services, and this would entail directing internet service providers to block access to such websites and/or streams. To date, there has been little action taken against online sites. Instead, the government changed tack in its approach to taxation. Rather than taxing the profitable foreign-based social media platforms or even local digital media publishers, a decision was made to tax individual users.

The Uganda Communications Commission (UCC), the government regulatory body of the communications sector, first called for regulation of social media platforms in 2016 with the executive director of the authority stating that “self-regulation is not sufficient and additional regulatory tools such as public supervision, legislations or even administrative measures are required.”10 Two years later, in July 2018, the UCC published a notice calling for online content providers including online publishers, news platforms, and radio and television operators to “apply and obtain authorization” for the provision of these services—potentially threatening access to information and free speech.11 The notice also stated that as of April 2, 2018, it would embark on enforcement activities against all non-compliant providers of online data communication services, and this would entail directing internet service providers to block access to such websites and/or streams. To date, there has been little action taken against online sites. Instead, the government changed tack in its approach to taxation. Rather than taxing the profitable foreign-based social media platforms or even local digital media publishers, a decision was made to tax individual users.

On July 1, 2018, the government introduced a tax on Over-The-Top (OTT) services, such as social media platforms, and added additional fees for mobile money transactions as part of the Excise Duty (Amendment) Act 2018.12 The amendment introduced a daily levy of 200 Ugandan shillings (about 5 US cents) on all users of social media platforms (e.g., Twitter, Facebook, Instagram) and a host of other voice and text message applications that transmit over the internet. It also introduced a 1 percent tax (later readjusted to 0.5 percent of the transaction value) on mobile money payments, transfers, and withdrawals. The act also increased the excise duty on mobile money fees from 10 to 15 percent. The new taxes marked a shift in the use of social media platforms, virtual private networks (VPNs), and mobile money for millions of Ugandan citizens.

Reactions to the Tax

Introducing the taxes led to widespread concern about the impact of these additional costs on financial and digital inclusion, data affordability, and access to information in the country. Meanwhile, members of civil society raised concerns about the impact of the taxes on freedom of expression and access to information.

Research ICT Solutions, an information technology think tank, released a study projecting that the taxes would cost the Ugandan economy up to 2.8 trillion Ugandan shillings (US$778 million) in forgone gross domestic product growth and 400 billion Ugandan shillings (US$10 million) in taxes per year, while also slowing down the country’s development.13 The study further noted that by imposing multiple taxation layers on a sector that is meant to be a growth engine, the state was instead penalizing the sector.

User reactions to the tax included immediately rejecting it, with many questioning its legitimacy. Following the introduction of the social media tax, a review of Facebook posts and Twitter entries revealed that many users were using virtual private networks to avoid paying. By first connecting to a VPN based outside of Uganda, users were then able to connect to social media sites without paying the tax. A January 2019 study revealed that although 56 percent of respondents paid the tax, 38 percent chose to use VPNs, and 3.7 percent resorted to accessing the internet only where free WiFi was available.14 Meanwhile, according to data released by the Uganda Communications Commission in January, in the first three months after the social media tax was implemented, only 50 percent of internet users in the country paid the daily levy, which suggested that the other half had either turned to VPNs or simply stopped connecting to those sites.15

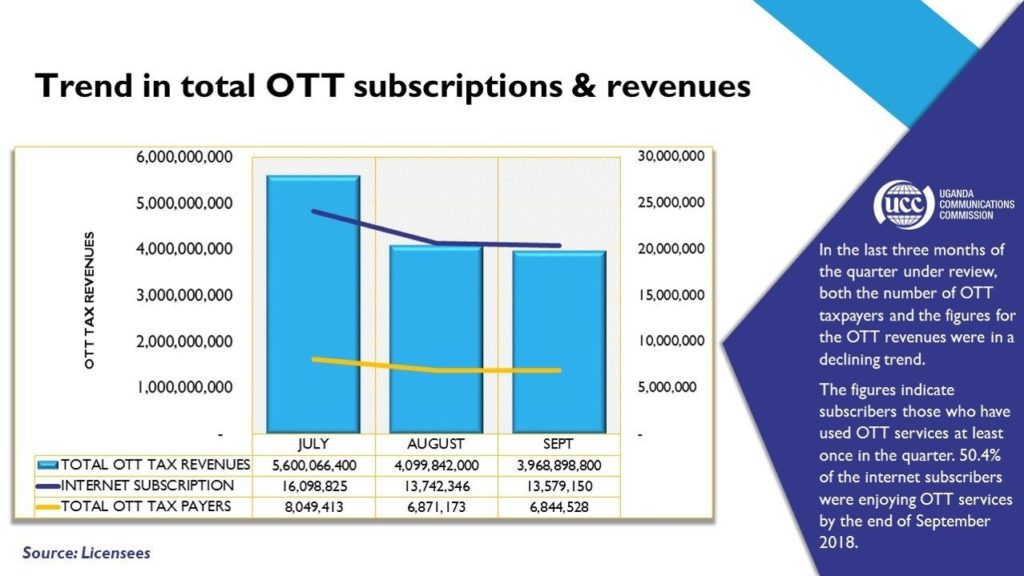

UCC slide representing drop in internet users and in revenues collected since the introduction of the social media tax in July 2018. Source: Uganda Communications Commission, Twitter post, January 25, 2019, https://twitter.com/UCC_Official/status/1088826901702078466.

The Uganda Communications Commission also released figures indicating that the state had lost revenue as a result of the drop in internet subscribers. In the first three months following the introduction of the tax in Uganda, internet penetration dropped from 47 percent to 35 percent according to data from the national communications regulator.16 This could be due to the rise in VPN subscriptions, which many users turned to in a bid to avoid paying the tax.17

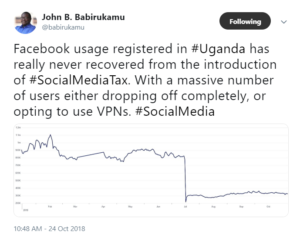

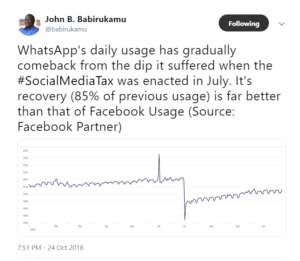

Ugandan social media, however, had already noticed this trend in declining internet activity. John Babirukamu, a digital communications manager at Uganda’s largest telecom, MTN Uganda, shared tweets in October 2018 depicting drops in the use of Facebook and WhatsApp. He noted that WhatsApp usage recovered more quickly than that of Facebook. This echoed the sentiment of a journalist interviewed as part of this research who noted that in the various media/journalist WhatsApp groups that she is in there had been a marked drop in the amount of “noise” in the initial days following the introduction of the tax. This drop in social media activity could have contributed to a slight increase in how long it takes to develop news content, which relies on information shared individually or through various social media platforms openly or in social media groups.

Uganda Is Not Alone

Over the course of 2018, a series of regulations were introduced in various African countries aimed at regulating online content including news and social media—ultimately aiming to shrink the space for online discourse. In April 2018, Tanzania issued online content regulations that oblige bloggers, owners of discussion forums, and radio and television streaming services to register with the communications regulator and pay hefty licensing and annual fees.18 In July, Egypt introduced a law to regulate social media that treats social media accounts with more than 5,000 followers as media outlets and thus opens Twitter and Facebook users to state prosecution for posted content.19

Over the course of 2018, a series of regulations were introduced in various African countries aimed at regulating online content including news and social media—ultimately aiming to shrink the space for online discourse. In April 2018, Tanzania issued online content regulations that oblige bloggers, owners of discussion forums, and radio and television streaming services to register with the communications regulator and pay hefty licensing and annual fees.18 In July, Egypt introduced a law to regulate social media that treats social media accounts with more than 5,000 followers as media outlets and thus opens Twitter and Facebook users to state prosecution for posted content.19

Meanwhile, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, a June 2018 decree gave all media houses (both online and offline) one month to comply with new rules, which included registering with the authorities, complying with a 1996 law on freedom of the press, and having advertisements approved by relevant authorities.20 In early July, Zambia’s government announced plans to enforce new rules to regulate social media with harsh penalties for noncompliance.

The Impact of the Tax and Regulations on News Media

Although legacy news media distribution still dominates Uganda’s media space, online content is slowly starting to take off.21 Social media have grown to serve as the entry point to the greater web by many novice internet users. However, instituting financial restrictions on social media access does little to promote an inclusive and affordable internet where users can interact “freely, safely and without fear.”22

Although legacy news media distribution still dominates Uganda’s media space, online content is slowly starting to take off.21 Social media have grown to serve as the entry point to the greater web by many novice internet users. However, instituting financial restrictions on social media access does little to promote an inclusive and affordable internet where users can interact “freely, safely and without fear.”22

While the tax has impacted the flow of communications on social media platforms, it appears to have had only minimal impact on the consumption of news content—at least news available on media house websites—including on the traffic to news sites.

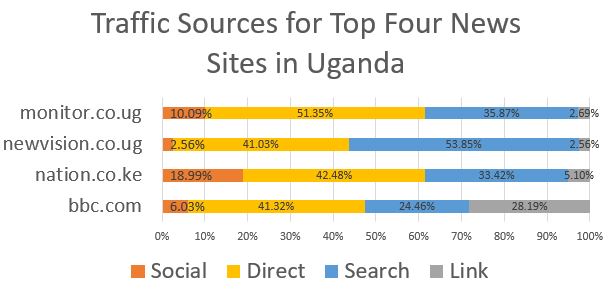

Social media referrals are not the primary driver of traffic to popular news sites visited by Ugandans according to Alexa Internet, a website ranking site. In fact, an analysis of popular news sites in Uganda revealed that traffic from social media was actually often behind both search referrals and direct traffic to websites as a referral mechanism. This was true for the top two Ugandan news sites, the Daily Monitor and New Vision. Of the four websites assessed, the Daily Nation newspaper in Kenya, which is one of the top visited news sites in Uganda, received the highest amount (19%) of traffic though social media.

Sales of the print edition of both papers did not significantly change either. The Audit Bureau of Circulations of South Africa, a nonprofit that tracks circulation of news outlets, reported that Daily Monitor circulation remained consistent from July to September 2018, with a circulation of 17,608, which was slightly higher than the previous reporting period with a circulation of 17,436.

Journalists noted that in the early days following the introduction of the taxes, there was a drop in the level of engagement that readers had with social media posts. Ruth Nasejje, a journalist with New Vision, noted a drop in the number of people reacting to or commenting on some of the news posts shared on the news sites’ social media platforms.

Clare Muhindo, a social media specialist with Daily Monitor, also noted a similar drop in online engagement on social media, but no discernible change in traffic to the daily’s website. Muhindo further noted that the news site has a large audience in the Ugandan diaspora, which may influence figures on who is accessing the website. In addition, she suggested that there was a slower feedback loop in the story development process with some content creators taking longer to source and verify content.

Meanwhile, Giles Muhame, editor of the news site Chimp Reports, said, “We have seen an increase in traffic to our website. We weren’t affected by the social media taxes.” He added: “Some media houses have hundreds of thousands of followers on social media but very little click through traffic. We have grown our social media traffic organically and weren’t even affected by the social media clean-up.” His last statement was in reference to a purge of fake accounts conducted by Twitter last year that reduced social media metrics for some outlets.23

Similarly, the Uganda Radio Network has also seen a rise in traffic to its site. Chief Editor Sylvia Nankya noted that the tax did not affect the network’s traffic. She added that this could be due to the audience it targets as it is a subscription-based independent news agency.

Prudence Nyamishana, a blogger and contributor to Stories for Human Rights and Social Inclusion, said that it was difficult to tell whether distribution of the stories on the site had been significantly affected by the tax even though it relies on social media to drive readers to its stories. She noted, “analytics cannot adequately tell whether taxes are to blame for low user content. Some stories simply attract more readers or engagement than others. Sometimes a story may attract more readers from outside Uganda even though it’s a Ugandan issue.”

Kampala Express, an independent online photo newspaper platform run by veteran journalist Timothy Kalyegira, doesn’t appear to have been affected either as no dramatic drop in the level of engagement on the page has been registered.24 Only on Facebook, Kampala Express has been run as an alternative to traditional media formats since 2014. Kalyegira, who was arrested in 2011 due to his critical content about the state,25 is in favor of the taxes and had hoped that there would be a more valuable narrative taking place online as opposed to the “fluff” commonly posted on social media. He noted that his news page had not been affected by the taxes and added that the taxes were “the right idea, right concept but the wrong government.” He added, “If the taxes were higher, that would maybe be better. We need people who can engage online, not simply read a headline and make baseless comments. While the internet has allowed for more people to post content, not everyone will uphold journalistic values in their narration, and thus threaten the nature of content found online.” He added that the taxes have done little to change the nature of content shared online.

Kampala Express, an independent online photo newspaper platform run by veteran journalist Timothy Kalyegira, doesn’t appear to have been affected either as no dramatic drop in the level of engagement on the page has been registered.24 Only on Facebook, Kampala Express has been run as an alternative to traditional media formats since 2014. Kalyegira, who was arrested in 2011 due to his critical content about the state,25 is in favor of the taxes and had hoped that there would be a more valuable narrative taking place online as opposed to the “fluff” commonly posted on social media. He noted that his news page had not been affected by the taxes and added that the taxes were “the right idea, right concept but the wrong government.” He added, “If the taxes were higher, that would maybe be better. We need people who can engage online, not simply read a headline and make baseless comments. While the internet has allowed for more people to post content, not everyone will uphold journalistic values in their narration, and thus threaten the nature of content found online.” He added that the taxes have done little to change the nature of content shared online.

He further argued that the tax is a “voluntary tax” in that it has no penalties, such as arrest, associated with it and that it was “priced rightly, being cheaper than a taxi ride or even mineral water.” Further, he stated that the tax could have the potential to make dramatic improvements to the lives of people—if it were used correctly—such as through improving basic public health services and other amenities. “It is not an ‘internet tax’; it’s a portion of the internet. Think beyond the current landscape—in the hands of the right government,” he added.

The Political Timing of the Social Media Tax

According to a 2016/17 Afrobarometer survey, 39 percent of Ugandans believe that the government “should have the right to prevent the media from publishing things that it considers harmful to society.” Attitudes in favor of state control of content are even more prevalent in Tanzania and Kenya.26 In these contexts where citizens are not already strongly predisposed to defend free expression, sweeping censorship actions, such as the social media tax, can normalize state control over content more easily than elsewhere. Some citizens get accustomed to suppressing their own online expression. They are less likely to defend the content of bloggers, social media commentators, and even traditional news outlets.

According to a 2016/17 Afrobarometer survey, 39 percent of Ugandans believe that the government “should have the right to prevent the media from publishing things that it considers harmful to society.” Attitudes in favor of state control of content are even more prevalent in Tanzania and Kenya.26 In these contexts where citizens are not already strongly predisposed to defend free expression, sweeping censorship actions, such as the social media tax, can normalize state control over content more easily than elsewhere. Some citizens get accustomed to suppressing their own online expression. They are less likely to defend the content of bloggers, social media commentators, and even traditional news outlets.

“When social media platforms emerged, they significantly changed the dynamics of journalism and traditional media. The platforms gave power to every user to communicate and inform. The idea that everyone wherever they are can post about happenings which the rest didn’t know about was revolutionary,” noted journalist Paul Ampurire in an opinion piece.27 On top of empowering them to do citizen journalism on their own, social media have enabled ordinary people to monitor professional journalists and have a say in how citizens are represented in the news. As Daniel K. Kalinaki, general manager of editorial at the Nation Media Group, stated in his keynote address to the 2016 Uganda Social Media Conference, “Tools such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, WhatsApp, Snapchat, and so on are spaces in which network effects are formed, bringing together producers and consumers of information and often blurring the lines in a constant feedback loop. Social media platforms are at once building blocks of a new relational dynamic and sledgehammers for dismantling established power structures around the flow and dissemination of information and the accruing power thereof as seen in traditional media.”28 Transforming Uganda’s Political and Social Landscape,” African Centre for Media Excellence, July 20, 2016, https://acme-ug.org/2016/07/20/how-social-media-are-transforming-ugandas-political-and-social-landscape/.’]

Kalinaki’s comments reinforce how regulations that push citizens off social media re-entrenches the old, undemocratic power dynamics around information flow. The most excluded will be women, rural community members, and low-income earners who were already disadvantaged due to prevailing socioeconomic inequalities. Excluding voices and input from these groups does not serve anyone any good, be it the readers, journalists, or even a nation that has stated intentions for democratic reform.

The taxes were introduced at a time when the political character of the country was being tested. Opposition party leader Robert Kyagulanyi—an increasing favorite among the country’s young population29—had faced repeated affronts including detention and treason charges.30 Kyagulanyi, who is also a musician, has been critical of the state in many of his songs. Over the course of 2018, he was denied the opportunity to perform and meet with constituents, and often took to his Facebook page to narrate his experiences. To many onlookers, the implementation of the social media tax at the very same time that the media-savvy opposition leader was being targeted seems like more than a coincidence. Indeed, this timing plays into the idea that the social media tax was intended to quell dissent.

Conclusion

Ugandan citizens have taken the new social media tax in stride. While some are paying it outright, more people than expected have discovered nimble ways to circumvent the barrier, primarily through the use of virtual private networks. While the Ugandan Communications Commission has registered an overall decrease in internet use, this drop has not necessarily translated into a corresponding fall in online news consumption. Web traffic to news websites has remained steady, which means that citizens continue to access news via the internet. However, journalists have noted that there has been less “noise” on social media, which has led to a slower feedback loop in terms of identifying emerging stories of interest to readers. Similarly, the dip in social media use has increased the time it can take to source and verify reporting for news stories as communicating with some sources has become more difficult.

Ugandan citizens have taken the new social media tax in stride. While some are paying it outright, more people than expected have discovered nimble ways to circumvent the barrier, primarily through the use of virtual private networks. While the Ugandan Communications Commission has registered an overall decrease in internet use, this drop has not necessarily translated into a corresponding fall in online news consumption. Web traffic to news websites has remained steady, which means that citizens continue to access news via the internet. However, journalists have noted that there has been less “noise” on social media, which has led to a slower feedback loop in terms of identifying emerging stories of interest to readers. Similarly, the dip in social media use has increased the time it can take to source and verify reporting for news stories as communicating with some sources has become more difficult.

While the impact of the social media tax specifically on news websites may not have been as detrimental as some had initially feared, it is also clear that there has been no demonstrable upside for journalists or the news media. In Uganda, the internet and access to social media have broadened the media ecosystem in Uganda and created multiple avenues for information sourcing and exchange in the country. From this perspective, the tax is a step in the wrong direction. That other governments in sub-Saharan Africa are implementing similar taxes is a worrying sign. Far from an attempt to improve the quality of the media ecosystem, they appear to be limiting access to news and information in highly unproductive ways.

Footnotes

- “Uganda Imposes WhatsApp and Facebook Tax ‘to Stop Gossip,’” BBC News, May 31, 2018, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-44315675.

- Emily Dreyfuss, “Uganda’s Regressive Social Media Tax Stays, at Least for Now,” Wired, July 19, 2018, https://www.wired.com/story/uganda-social-media-tax-stays-for-now/.

- Communication on government achievements, http://gcic.gou.go.ug/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Letter-HE-COMMUNICATING-GOVERNMENT-ACHIEVEMENTS.pdf

- “Communications in Uganda: A Look at One of Africa’s Fastest Growing Markets,” ITU News, July-August 2009, https://www.itu.int/net/itunews/issues/2009/06/31.aspx.

- Uganda Communications Commission, Postal, Broadcasting and Telecommunications Annual Market & Industry Report 2016/17, 2017, https://www.ucc.co.ug/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Annual-Market-Industry-Report-2016-17-FY.pdf.

- National Information Technology Authority – Uganda, Government of Uganda Social Media Guide, July 2013, https://www.nita.go.ug/publication/government-uganda-social-media-guide.

- Elias Biryaberema, “Uganda Bans SMS Texting of Key Words During Poll,” Reuters, February 17, 2011, https://www.reuters.com/article/ozatp-uganda-election-telecoms-idAFJOE71G0M520110217.

- Juliet Nanfuka, “Uganda Again Blocks Social Media to Stifle Anti-Museveni Protests,” Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa, May 12, 2016, https://cipesa.org/2016/05/uganda-again-blocks-social-media-to-stifle-anti-museveni-protests/.

- “Uganda’s Assurances on Social Media Monitoring Ring Hollow,” Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa, June 10, 2013, https://cipesa.org/2013/06/ugandas-assurances-on-social-media-monitoring-ring-hollow/.

- Techjaja Staff, “UCC Boss Calls for the Regulation of Social Media in Uganda,” Techjaja, June 22, 2016, https://www.techjaja.com/ucc-boss-calls-regulation-social-media-uganda/.

- Daniel Mwesigwa, “Uganda Moves to Register Online Content Providers,” Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa, March 25, 2018, https://cipesa.org/2018/03/uganda-moves-to-register-online-content-providers/.

- Godfrey Mwesigye, “The Excise Duty (Amendment) Act, 2018: A Progress for Uganda’s Economy or an Impediment to Telecommunication?” Parliament Watch, 2018, http://parliamentwatch.ug/the-excise-duty-amendment-act-2018-a-progress-for-ugandas-economy-or-an-impediment-to-telecommunication/#.XG6uCegzZPY.

- “ICT Sector Taxes in Uganda – Unleash, Not Squeeze, the ICT Sector,” Research ICT Solutions, August 24, 2018, https://researchictsolutions.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Unleash-not-squeeze-the-ICT-sector-in-Uganda.pdf.

- Policy, Offline and Out of Pocket: The Impact of the Social Media Tax in Uganda on Access, Usage, Income and Productivity, January 2019, http://pollicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Offline-and-Out-of-Pocket.pdf.

- Uganda Communications Commission, Third Quarter Communication Industry Report, 2018.

- Ibid.

- Frank Kisakye, “Ugandans Again Run to VPN as Social Media Tax Starts to Bite,” The Observer, July 1, 2018, https://observer.ug/news/headlines/58064-ugandans-again-run-to-vpn-as-social-media-tax-starts-to-bite.html.

- Ashnah Kalemera, “Tanzania Issues Regressive Online Content Regulations,” Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa, April 12, 2018, https://cipesa.org/2018/04/tanzania-enacts-regressive-online-content-regulations/.

- Marwan Shalaby, “Egyptian Parliament Passes Law to Regulate Social Media Users with over 5000 Followers,” Egyptian Streets, June 12, 2018, https://egyptianstreets.com/2018/06/12/egyptian-parliament-passes-law-to-regulate-social-media-users-with-over-5000-followers/.

- AFP, “Media Curbs in DRC Raise Fears ahead of Presidential Vote,” New Vision, July 14, 2018, https://www.newvision.co.ug/new_vision/news/1481431/media-curbs-drc-raise-fears-ahead-presidential-vote.

- “Digital Inclusion in Uganda,” DW, October 4, 2018, https://www.dw.com/en/digital-inclusion-in-uganda/a-45758739.

- Ian Sample, “Tim Berners-Lee Launches Campaign to Save the Web from Abuse,” The Guardian, November 5, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/nov/05/tim-berners-lee-launches-campaign-to-save-the-web-from-abuse.

- Emily Stewart, “Twitter’s Wiping Tens of Millions of Accounts from Its Platform, Vox, July 11, 2018, https://www.vox.com/2018/7/11/17561610/trump-fake-twitter-followers-bot-accounts.

- Kampala Express, Facebook page, https://web.facebook.com/TheKampalaExpress/.

- “Ugandan Online Editor Arrested for Publishing Op-Eds,” Biz-Community, June 2, 2011, https://www.bizcommunity.ug/Article/220/466/60163.html.

- “Do East Africans Still Want a Free Media? Afrobarometer Finds Weakening Popular Support,” Afrobarometer, May 21, 2018, http://afrobarometer.org/press/do-east-africans-still-want-free-media-afrobarometer-finds-weakening-popular-support.

- “Opinion: Social Media Tax – Citizen Journalism Is Probably the Biggest Loser,” SoftPower News, July 9, 2018, https://www.softpower.ug/opinion-social-media-tax-citizen-journalism-is-probably-the-biggest-loser/.

- ’“How

- “Bobi Wine Re-arrested, Charged with Treason,” The Observer, August 23, 2018, https://observer.ug/news/headlines/58504-state-drops-charges-against-bobi-wine.html.