Key Findings

Strategic lawsuits against public participation, or SLAPPs, are lawsuits taken against media organizations or activists with the sole purpose of silencing them. They typically involve a huge disparity in resources and the claimant’s tactic is to use the lawsuit, or threat of a lawsuit, to divert a journalist or media organization’s resources. Cases are reported in increasing numbers across Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Americas. The damage done by SLAPPs is far-reaching and curbing it is an imperative for media freedom.

In many countries, law reform is critical but not the only response. This report discusses tactics that journalists, activists, and defense lawyers can use to defang SLAPPs, including setting up mutual insurance mechanisms, pooling resources, and advocating for changes to court rules. These measures strengthen the resilience of independent media outlets and, as a carefully targeted package, they can do much to alleviate the burden of defending SLAPPs.

– Legal reform is a difficult process that can often take years to achieve. There are several short-term measures available to minimize the damage SLAPPs can inflict upon journalists, from pre-publication vetting to innovative lawyering .

– Media development donors can support these initiatives through more than just direct funding. Supporting the development of media defense coalitions and facilitating the creation of peer learning spaces for the communities of public interest lawyers who take on SLAPPs cases are crucial to fighting these frivolous lawsuits.

– There is no silver bullet to respond to SLAPPs. A contextually-tailored package of measures should be implemented to boost a media outlet’s resilience in the face of legal harassment.

The Issue

Strategic lawsuits against public participation, or SLAPPs, are lawsuits taken against media organizations or activists with the sole purpose of silencing them. This purpose can be achieved effectively by tying up a journalist or an activist in lengthy and therefore costly legal proceedings, requiring them to invest time and money in their legal defense. In SLAPP cases, there is often a huge disparity in resources. The claimant is usually a large company, politician, or businessperson with access to significant resources, while the defendant typically has far fewer resources. For the claimant, the cost of launching a case is comparatively small, whereas for the defendant the cost of hiring lawyers and the risk of having to pay the claimant’s legal costs means their livelihood may be on the line. Consider this, from a notorious and very wealthy SLAPP claimant, about a journalist he sued:

“I spent a couple of bucks on legal fees and they spent a whole lot more. I did it to make his life miserable, which I’m happy about.”1

The term SLAPP was coined in the 1980s by academics who researched lawsuits against nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and citizen associations in the United States.2 Since then, the phenomenon has gone global. Wealthy claimants have discovered that the law can be a powerful tool to silence their opponents. To achieve this purpose, a claimant doesn’t even need to win a case: Keeping a defendant tied up in court can be enough to divert all of their resources. And if a claim is dismissed, a new one is easily filed.

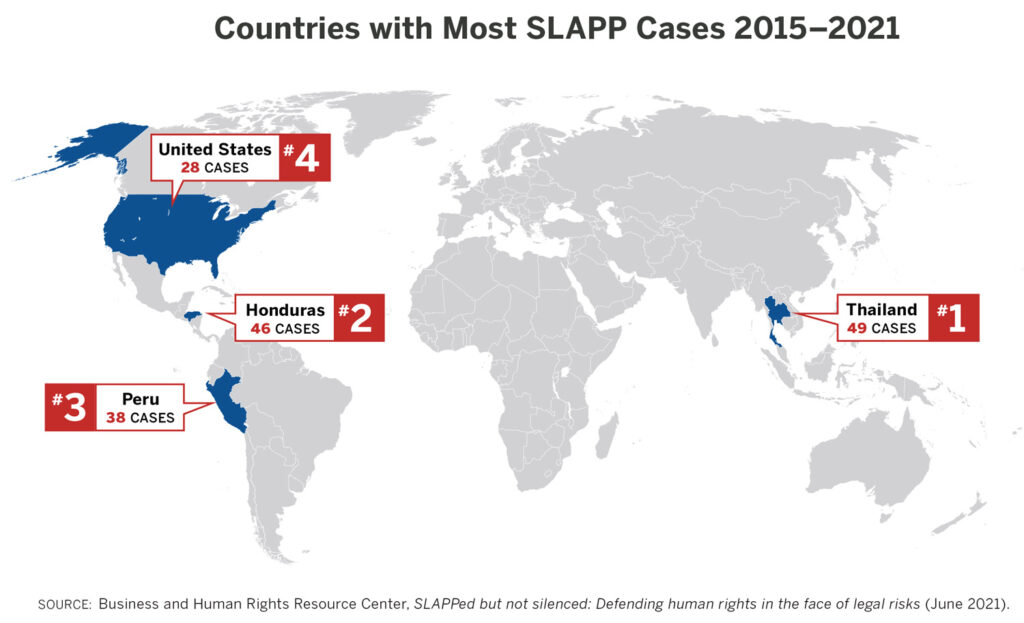

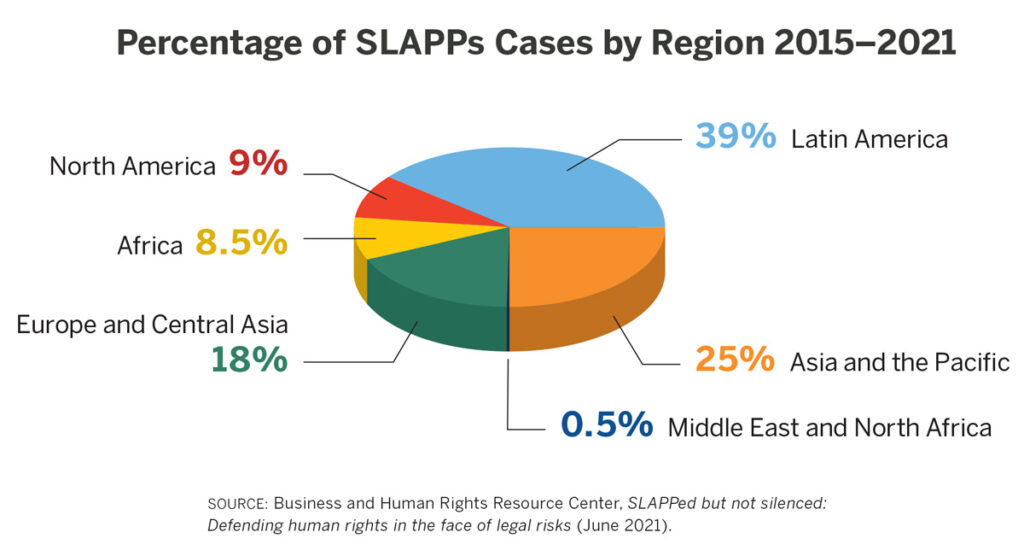

Cases are reported in increasing numbers across Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Americas. There are no official statistics—save for a few countries, the term SLAPP is not defined in law—but anecdotal evidence from media outlets and NGOs suggests the number is growing. The Business & Human Rights Resource Centre reported 355 cases against human rights defenders from 2015 to 2021, with most cases brought in Latin America, followed by Asia and the Pacific.3 This is likely just the tip of a sizeable iceberg. European human rights and media freedom organizations have reported hundreds of cases across the continent in the last few years alone.4

Media Defence, an NGO that specializes in providing legal defense to independent media outlets and journalists, reported that during 2020-2022 it provided legal support in 202 SLAPP cases in dozens of countries, accounting for 45 percent of its overall caseload.5 Snezana Green, senior legal counsel at the Media Development Investment Fund, which invests in independent media, says:

“The practice of abusing legal systems by those in power to silence critics has reached global proportions. Its damage is far-reaching and curbing it is an imperative for democracy and maintaining peace.”6

SLAPP suits typically target independent media outlets as well as academics and civil society organizations. The claimants aim to silence reporting that is critical of them, using whatever law—criminal or civil—is most convenient.7 Not all cases go to court. The burden of defending a case means that just threatening litigation can be enough for a media outlet to withdraw a report or issue an apology. As freedom-of-expression NGO ARTICLE 19 notes:

“Several law firms, most notably in the UK [United Kingdom] but also in other countries, have developed very aggressive tactics to essentially bully journalists and media outlets into self-censorship, usually on behalf of wealthy clients.”8

The majority of SLAPP cases concern defamation, which is an area of law that is easily exploited by claimants. Generally, the only requirement for a claimant to bring a defamation case is to assert that something that has been published harms their reputation. The burden then shifts to the defendant to mount a defense. In practice, this places a significant burden on journalists because defamation law is complex and technical, and the evidentiary threshold is high.

There may also be practical issues that make defending a case difficult. A journalist may be sued hundreds of miles from where they live or even in another country, forcing them to travel and hire lawyers in a foreign place. In some countries, defendants are required to pay a surety into court or even have their bank accounts frozen.9 But it’s not just defamation laws: SLAPP claimants have also abused laws on privacy, data protection, copyright, and tax.10 The legal procedure in many of these cases means that a claimant is often able to drag out a case over months or years, requiring the journalist to invest in their legal defense over a prolonged period.11

The true costs of SLAPPs are difficult to estimate. Beyond legal fees, journalists and media outlets might have to pay for discovery costs and for travel to and from the country where the suit was brought. Paul Radu, co-founder of the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), was sued for reporting on a large-scale money laundering scheme in Azerbaijan. Radu, who is based in Romania, was sued for defamation in London by the implicated politician. As part of the discovery process, Radu had to pay around $40,000 to have his computers and phones searched. Before the case was eventually settled, the OCCRP had spent around $500,000 on travel and other fees, despite having had pro bono legal support.12 Journalists often have to deal with more than one such lawsuit at a time, which can be a massive drain on their time and resources. At the time of her death, Maltese journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia had more than 40 lawsuits against her, several of which were still ongoing posthumously.13 Similarly, as of December 2021, Serbian investigative news outlet KRIK was subject to 10 lawsuits seeking total damages of almost $1 million—three times KRIK’s annual budget.14 These threats can have a chilling effect on journalists. According to a survey of 63 journalists across 41 countries developed by the Foreign Policy Centre, 73 percent of journalists were threatened with legal action. As a result of the threats they faced, 70 percent of respondents indicated that they had self-censored to some degree.15

The true costs of SLAPPs are difficult to estimate. Beyond legal fees, journalists and media outlets might have to pay for discovery costs and for travel to and from the country where the suit was brought. Paul Radu, co-founder of the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), was sued for reporting on a large-scale money laundering scheme in Azerbaijan. Radu, who is based in Romania, was sued for defamation in London by the implicated politician. As part of the discovery process, Radu had to pay around $40,000 to have his computers and phones searched. Before the case was eventually settled, the OCCRP had spent around $500,000 on travel and other fees, despite having had pro bono legal support.12 Journalists often have to deal with more than one such lawsuit at a time, which can be a massive drain on their time and resources. At the time of her death, Maltese journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia had more than 40 lawsuits against her, several of which were still ongoing posthumously.13 Similarly, as of December 2021, Serbian investigative news outlet KRIK was subject to 10 lawsuits seeking total damages of almost $1 million—three times KRIK’s annual budget.14 These threats can have a chilling effect on journalists. According to a survey of 63 journalists across 41 countries developed by the Foreign Policy Centre, 73 percent of journalists were threatened with legal action. As a result of the threats they faced, 70 percent of respondents indicated that they had self-censored to some degree.15

Supporting journalists and media organizations targeted by SLAPPs can be complicated. In many of the countries where SLAPPs are an issue, the underlying legislation is a fundamental part of the problem that law reform is required to definitively solve. However, such reform processes are often time consuming and politically sensitive, requiring long-term investments from advocates on the ground, as well as the international community. At the same time, media development organizations cannot simply cover the costs for journalists facing these lawsuits. For one, covering the costs does not address practical issues involved in resolving the case, such as the inconveniences of being forced to travel to the country where the suit was brought or having a bank account frozen. This tactic could also encourage claimants to keep bringing onerous suits to drain money from donors.

Alongside advocating for law reform, other tactics journalists, activists, and defense lawyers can use to defang SLAPPs include setting up mutual insurance mechanisms, pooling resources, and advocating for changes to court rules to empower SLAPP defendants. These strategies are aimed at strengthening the resilience of independent news outlets and ensuring that court procedures are not abused to restrict rights. They require the support and cooperation of several stakeholders, including media development donors and lawyers, as well as journalists and activists.

What Can Be Done?

The burden of defending cases is a fundamental part of the problem posed by SLAPPs. Journalists and editors have spoken about the toll these lawsuits take. Journalists can sometimes be forced to spend more time on their legal defense than on their journalism. They also must spend huge sums of money on legal fees, and they struggle with the potential reputational damage a lawsuit can cause.16 The emotional toll is also exhausting. All of this, more than winning the case, is precisely what a SLAPP claimant aims to achieve. For that reason, alleviating the burden of defending SLAPPs is key to diminishing the threat they pose.

Resourcing the Media to Resist SLAPPs

Covering the Cost: Insurance and Legal Defense Funds17

The financial cost of defending a SLAPP can be huge. Lawyers are expensive and defending several cases simultaneously can cause costs to skyrocket.

A systematic way of covering legal costs is through insurance. Large media outlets and even some NGOs have defamation insurance. Drew Sullivan, co-founder and publisher of the OCCRP, has been sued for defamation dozens of times and credits having insurance as the primary reason that the OCCRP has been able to fend off these claims. However, for smaller outlets, the cost of insurance is itself prohibitively expensive. There are other drawbacks as well. Premiums are high, the deductible can be tens of thousands of dollars, and insurance companies sometimes stop covering outlets that have been sued or raise their premiums to an unaffordable level. In many countries, insurance is simply not available.

To remedy this, the United States Agency for International Development announced in June 2022 that they would provide in $9 million in seed funding for Reporters Shield—a defense fund that journalists and activists around the world can use to protect themselves against SLAPPs and other bogus lawsuits.18 The fund, which is being developed by the OCCRP and the Cyrus R. Vance Center for International Justice of the New York City Bar Association, aims to become a viable, self-sustaining nonprofit entity and is set to launch in 2023. The fund would sustain itself through membership fees from participating media organizations. However, since it will be run as a not-for-profit, it will be far cheaper than for-profit insurance, making it a potential game-changer for independent media.19

To remedy this, the United States Agency for International Development announced in June 2022 that they would provide in $9 million in seed funding for Reporters Shield—a defense fund that journalists and activists around the world can use to protect themselves against SLAPPs and other bogus lawsuits.18 The fund, which is being developed by the OCCRP and the Cyrus R. Vance Center for International Justice of the New York City Bar Association, aims to become a viable, self-sustaining nonprofit entity and is set to launch in 2023. The fund would sustain itself through membership fees from participating media organizations. However, since it will be run as a not-for-profit, it will be far cheaper than for-profit insurance, making it a potential game-changer for independent media.19

Another way of ensuring the availability of low-cost or even free defense lawyers is through legal defense funds, or the in-house lawyers of journalists’ associations. Legal defense funds are a well-known vehicle used to defend legal costs in many countries, often in aid of the less privileged in society, and can be used to pay for legal costs, bail, court fees, and even fines.20 The global Legal Network for Journalists at Risk coordinates support from various organizations that provide funding separately,21 including London-based NGO Media Defence, which operates a global legal defense fund for independent media alongside its legal training, capacity building, and strategic litigation work.22 This is a promising development, but it should be noted that even the combined capacity of these defense funds is limited, and journalists are not always aware of them. Although there are no statistics, anecdotal evidence indicates that the demand for legal assistance outstrips the capacity of defense funds and NGOs to support it.

Pre-publication Vetting; Pooling Resources

Pre-publication vetting identifies potential legal weaknesses in an article. Good pre-publication vetting requires a partnership between a lawyer and journalist, with the lawyer understanding the article that the journalist seeks to publish and the journalist seeing the lawyer as a partner.23 While for some journalists this may be reminiscent of the “bad old days” of government censorship, pre-publication vetting is highly recommended for investigative reporting, as well as for any articles on individuals or corporations known to be litigious. Although vetting does not guarantee that a journalist will not get sued, it means that, if they do, they will be well prepared to mount a strong legal defense. For this reason, many insurance schemes, including the Reporters Mutual, require articles to be vetted to be eligible for coverage.

Unfortunately, as with insurance, many journalists and media outlets lack the resources to have reports vetted. In such cases, not-for-profit or pro bono pre-publication vetting initiatives can provide a solution. Organizations in some countries already do this. For example, the US Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press provides pro bono pre-publication vetting for investigative reporters and local journalists. Vaša prava BiH in Bosnia provides several legal services, including pre-publication vetting, and in Malta, the Daphne Caruana Galizia Foundation has engaged one of the country’s foremost media lawyers to provide pre-publication vetting to independent media at no cost.24 University law clinics can also help with the work being done under the supervision of a qualified lawyer. In the United States, a nationwide coalition of law school clinics provides legal advice, and launches and follows up on access-to-information requests on behalf of journalists.25 Similarly, in 2015, the Croatian Journalists’ Association set up the Center for the Protection of Freedom of Expression, which offers legal defense for journalists targeted by SLAPPs, as well as legal counseling and educational resources from local lawyers and law school staff.26

Unfortunately, as with insurance, many journalists and media outlets lack the resources to have reports vetted. In such cases, not-for-profit or pro bono pre-publication vetting initiatives can provide a solution. Organizations in some countries already do this. For example, the US Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press provides pro bono pre-publication vetting for investigative reporters and local journalists. Vaša prava BiH in Bosnia provides several legal services, including pre-publication vetting, and in Malta, the Daphne Caruana Galizia Foundation has engaged one of the country’s foremost media lawyers to provide pre-publication vetting to independent media at no cost.24 University law clinics can also help with the work being done under the supervision of a qualified lawyer. In the United States, a nationwide coalition of law school clinics provides legal advice, and launches and follows up on access-to-information requests on behalf of journalists.25 Similarly, in 2015, the Croatian Journalists’ Association set up the Center for the Protection of Freedom of Expression, which offers legal defense for journalists targeted by SLAPPs, as well as legal counseling and educational resources from local lawyers and law school staff.26

Pooling legal resources is another option. With the increase in collaborative journalism projects, media outlets are already sharing resources more frequently, including administrative resources and digital services. This could extend to legal services. There are some examples of such collaborations: the Southern African Investigative Journalism Hub provides shared resources to its members including access to legal advice.27 Using the same group of lawyers has the additional benefit that these lawyers build expertise in the area of media law, which, in many countries, is not a distinct field of practice. But there are drawbacks as well. If only a few lawyers take all media cases, this may lead to real or perceived conflicts of interest for those lawyers.

Supporting Innovative Lawyering

Successfully forging a new defense out of constitutional or international rights protections is a particularly powerful way of resisting a SLAPP lawsuit. A single positive judgment can introduce a new legal defense or provide for summary dismissal for an entire class of cases, benefiting not just the journalist or outlet in the case, but a country’s entire media. The Mineral Sands case in South Africa is a great example. This concerned a SLAPP brought by an Australian mining company and its local subsidiary against environmental and community activists who had criticized the mining operations. The companies sued for an apology or damages of R14.25 million (nearly $1 million). The defendants claimed that this was a typical SLAPP case and constituted an “abuse of process.” There is no specific anti-SLAPP law in South Africa, but the legal team grounded their arguments in common law—a body of law rooted in the ancient English legal system that can be developed by courts without the need for legislation. The South African Constitutional Court agreed, stating that in SLAPP cases,

“the court process is not being used to resolve a genuine dispute, but rather is employed to achieve a result that undermines the rights in the Constitution . . . If the case ultimately succeeds, the court would not be ensuring that justice is done as the overriding principle, but would instead be the means to an end that is likely to gravely harm fundamental rights. This the court cannot allow. Courts have the power to prevent this type of abuse.”28

The Court noted the absence of a legal framework to challenge SLAPPs in South Africa, but was convinced by arguments brought by lawyers for the activists that the existing common law defense of ‘abuse of process’ can accommodate a SLAPP defense. The Court emphasized that this was important to “ensure that the law serves its primary purpose, to see that justice is done, and not to be abused for odious, ulterior purposes.”29

While the case was novel in South Africa, it built on arguments that have been accepted by courts in other countries. One of the features of common law is that courts are open to hearing arguments and developments from other common law jurisdictions. The South African court surveyed a large body of US and Canadian law. At an earlier stage in the same proceedings, the Western Cape High Court had similarly agreed that a SLAPP defense could be fashioned from the common law and had cited a 2006 UK House of Lords judgment, in which one the judges said:

“The power wielded by the major multi-national corporations is enormous and growing. The freedom to criticise them may be at least as important in a democratic society as the freedom to criticise the government.”30

International human rights law provides another route through which innovative legal defenses can be developed, especially at courts that sit at the apex of the regional human rights systems: the European Court of Human Rights, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights, and the regional courts of the East and West African economic communities, which have some jurisdiction over human rights cases. Each of these courts delivers judgments that are binding on states and they frequently cite each other, thus building a common international set of norms in human rights cases, including on the right to freedom of expression.31

For example, the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights’ 2015 judgment in the defamation case of Konaté v. Burkina Faso has been influential in striking down criminal defamation laws and abolishing imprisonment for defamation across Africa. The court overturned the conviction of Lohé Issa Konaté, a journalist who faced criminal penalties for a series of articles alleging that a state prosecutor engaged in corruption. A case study of the judgment conducted by Media Defence, whose lawyers represented Konaté before the African Court, found that the judgment had not only changed the law in Burkina Faso—it had informed the judiciary worldwide through its inclusion in international curricula and influenced several later judgments.32

The European Court of Human Rights’ free speech jurisprudence has been similarly influential. It has handed down dozens of judgments in defamation cases highlighting the importance of freedom of expression. Recently, the court explicitly mentioned the need to act against SLAPP claimants, holding that a defamation lawsuit brought by a Russian regional government body against the independent media outlet Caucasian Knot for its reporting on a local budget conflict “did not pursue any . . . legitimate aims.” The judgment, which cites the Council of Europe human rights commissioner, who said it’s “time to take action against SLAPPs,”33 can be expected to be influential in other cases and before other courts.34

The media development community can support innovative lawyering directly as well as indirectly. UNESCO’s Global Media Defence Fund, for example, provides financial support for structures that foster strategic litigation to protect media in contexts “that are conducive to an independent, free and pluralistic media ecosystem.” It has funded litigation efforts in several countries.35 Cases such as Mineral Sands can be defended by media outlets only when they are sufficiently stable financially, and when their owners, investors, and donors support them in decisions to stand by their reporting and go to court instead of issuing an apology or retraction when faced with a legal demand. Donors can also provide support for tools such as case law databases and lawyers’ networks.36

The media development community can support innovative lawyering directly as well as indirectly. UNESCO’s Global Media Defence Fund, for example, provides financial support for structures that foster strategic litigation to protect media in contexts “that are conducive to an independent, free and pluralistic media ecosystem.” It has funded litigation efforts in several countries.35 Cases such as Mineral Sands can be defended by media outlets only when they are sufficiently stable financially, and when their owners, investors, and donors support them in decisions to stand by their reporting and go to court instead of issuing an apology or retraction when faced with a legal demand. Donors can also provide support for tools such as case law databases and lawyers’ networks.36

There are also a number of international, regional, and local organizations researching SLAPPs and effective countermeasures. The High Level Panel of Legal Experts on Media Freedom, an independent group of lawyers and judges convened by the governments of the United Kingdom and Canada in 2019 as part of the Media Freedom Coalition to provide advice and recommendations to governments to prevent and reverse abuses of media freedom. As part of its work, it is putting together a series of briefings reviewing the laws that are most frequently used to target media freedom and providing guidance on how these laws might be amended to comply with international human rights standards. These reports can then be used by legislators, but also by lawyers, in crafting innovative legal arguments. Specialist legal groups exist in several countries. Media Defence provides funding and works in partnership with a network of 14 organizations across Africa, Asia, the Americas, and Europe, all of which engage in media defense litigation at the national level, as well as before regional human rights courts. Fostering strategic litigation for media freedom and ensuring access to legal defense for journalists are among the priorities of UNESCO’s Global Media Defence Fund. In May 2022, it announced a $1.4 million funding round for projects that pursued either of these goals, or that supported investigative journalism.37 In Turkey, the Media and Law Studies Association, which provides pro bono legal support to journalists and activists, has been sounding the alarm on the weaponization of SLAPPs against journalists.38

A final form of innovative lawyering is lawyers not taking cases. When a client asks a law firm to threaten or initiate a lawsuit that would constitute a SLAPP, the firm could refuse to take the case. There is precedent for this. In the UK, long the “home of libel,” there is increasing discussion about the ethics of taking SLAPPs, and the Solicitors Regulation Authority has updated its guidance urging lawyers not to represent clients in SLAPP suits and to report any lawyers who do.39 In the United States, lawyers who are members of the Media Law Resource Center voluntarily pledge not to represent claimants in defamation, privacy, and related lawsuits or claimants who threaten such lawsuits.40 A more ethical stance by lawyers approached by would-be SLAPP claimants would be welcome in other countries as well.

Sunlight Is the Best Disinfectant: Speaking Out, Solidarity, and Profiling SLAPP Claimants

For many journalists, getting sued is a nerve-wracking and frightening experience. The bullying tactics used by claimant lawyers are designed to silence them, including about the fact that they are under threat. Letters threatening a lawsuit are usually phrased in harsh terms and are marked “private and confidential,” seemingly prohibiting journalists from publishing them. They are designed to intimidate. Calling the lawyers’ bluff and publishing the letter alongside reasons the media outlet intends not to comply can be a powerful tactic of resistance. Examples of journalists doing this successfully include Maltese media outlet The Shift, which called out a threatened lawsuit by the notorious litigant Henley & Partners; and South Africa’s Daily Maverick, which publishes threat letters alongside editorials defending its stance.41 As long as their work is good, journalists should not fear going public about the threat of a lawsuit. As Estonian journalist Anna Pihl, who was sued in relation to her work on organized crime, says: “You don’t have to be worried that you can’t write your stories if you’ve done everything correctly. If your work is of a high standard, in the end the journalist will win.”42 However, when a journalist decides to do this, they should first seek advice from their own lawyers. As with pre-publication vetting, the journalist-lawyer partnership is key to success.

Speaking out also creates greater solidarity. It can result in better access to financial resources or pro bono support, and eases the emotional toll of defending SLAPP suits (the psychological toll of defending SLAPP suits can be particularly heavy). The activists who fought the Mineral Sands case in South Africa came together in the “Asina Loyiko” campaign (an isiXhosa phrase that means “we have no fear”), which has since its launch grown into an international campaign against “corporate bullying” and provides resources to victims of SLAPP lawsuits.43 The Coalition against SLAPPs in Europe (CASE) and, in the United States, Protect the Protest are similar examples of how to build power through solidarity.44

Profiling companies that repeatedly bring SLAPP suits against journalists and activists can be a powerful way of shining a light on those who seek to abuse the legal system for their own gain. By documenting previous lawsuits and threats brought by a given company, news outlets and civil society organizations can demonstrate a pattern of abuse by claimants. This strategy played an important part in the “abuse of process” defense used in the Mineral Sands case in South Africa and has been suggested in other countries as well.45 The defendants in the Mineral Sands case argued that the intention of the claimant was to silence them, as evidenced by the “pattern of conduct by the mining companies in which they seek to bring defamation actions for these purposes.”46

Regulatory Reform

Changing defamation or privacy laws is usually a lengthy and controversial process. Changing court rules or introducing secondary legislation can be done far more quickly. This can include measures such as capping the cost of legal defense, instituting early dismissal provisions, or expanding the availability of legal aid.

In some countries, access to legal aid can be a relatively simple and powerful way of alleviating the impact of SLAPPs. Kosovo recently became the first European country to expressly include “journalists, independent journalists, photojournalists, cameramen and editors” as eligible for legal aid, for the defense of cases against them, as well as for legal advice relevant to their work.47 Legal aid is not a panacea, however. In some countries, it may be insufficient to cover all the costs for legal defense. Legal aid budgets may simply not be large enough to cover all who need it, and eligibility requirements may rule out some defendants.48

The sheer length of many SLAPP proceedings is another issue that contributes to the huge financial and emotional burden of defending SLAPPs. Reforming court procedure so that SLAPPs can be dismissed at an early stage would be a powerful regulatory move. Such early dismissal provisions are a key feature of anti-SLAPP laws in several US states, as well as in Canada, either disallowing lawsuits filed for an improper purpose or creating a protected class of cases arising from the exercise of the right to freedom of expression on issues of public interest.49 In the UK, following urgent consultation to take action against SLAPPs, the Ministry of Justice in July 2022 proposed introducing a three-part test to determine whether a case can be thrown out early.50 For this solution to be impactful, it is important that the claimant should have the burden to prove that their case is not a SLAPP. If there is a high burden of proof on the defendant that a case against them is a SLAPP, they will still be required to invest significant resources in their legal defense, which runs counter to the aim of alleviating the burden on defendants.

There is precedent for similar procedures outside of Europe and North America as well. In the Philippines, for example, the Supreme Court Rules of Procedure were amended in 2010 to allow for early dismissal of SLAPP cases against environmental rights activists as well as journalists reporting on environmental rights issues.51 The International Center for Not-for-Profit Law reported a decline in the number of SLAPP cases after this provision was introduced.52 In Thailand, the Criminal Procedure Code was amended in 2019 to require the dismissal of private criminal cases meant to harass or take advantage of a defendant.53

Another regulatory reform to reduce costs is to cap the costs in proceedings. This limits the amount of costs that a winning party can recover from the losing side in the litigation, diminishing the financial pressure that a claimant can put on a defendant in a SLAPP (a claimant is free to spend more on their legal team but will not be able to recover the additional costs should they win). Cost capping orders are usually made by a judge. This, too, has been announced as among the package of procedural reforms in the UK. It can be introduced without the need to change legislation, meaning it can be done fairly quickly.54 It has also been suggested that many defamation cases could be heard as fast track cases or small claims cases, which could make them quicker and far cheaper to defend.55

Another regulatory reform to reduce costs is to cap the costs in proceedings. This limits the amount of costs that a winning party can recover from the losing side in the litigation, diminishing the financial pressure that a claimant can put on a defendant in a SLAPP (a claimant is free to spend more on their legal team but will not be able to recover the additional costs should they win). Cost capping orders are usually made by a judge. This, too, has been announced as among the package of procedural reforms in the UK. It can be introduced without the need to change legislation, meaning it can be done fairly quickly.54 It has also been suggested that many defamation cases could be heard as fast track cases or small claims cases, which could make them quicker and far cheaper to defend.55

A final proceedings-related measure is awarding costs to successful defendants, and even imposing punitive awards against unsuccessful claimants. There is precedent for this in various countries.56 The drawback of these measures is that, while they will help a successful SLAPP defendant once the case has been won, they offer no help during the proceedings, which, as noted, can drag on for years. It is also questionable whether a punitive cost award really is a deterrent for a wealthy claimant, especially when they still achieve their objective of disrupting the work of a journalist or an activist over a long period.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The global SLAPP crisis is posing a serious threat to the work of many journalists, activists, and independent media outlets. To alleviate the burden these suits place on independent media, lawyers and media support organizations must pursue pragmatic solutions alongside or as a short-term alternative to reforming defamation and other laws. Although such reform is necessary, the reality is that achieving it is a long, arduous, and unpredictable process.

There is no silver bullet to the problem of SLAPPs. In every country, the situation needs to be carefully analyzed and a package of measures tailored to the country situation should be pursued. It may well be that in some countries none or only some of these short-term measures will work. For example, where the judiciary is not independent and the outcome of a trial is a foregone conclusion, cost-capping or a media insurance policy will not help. However, in many countries there is scope for introducing the tactics and strategies discussed in this report and if several of these solutions are implemented alongside one another, as a package of measures, there is no doubt that this will make news outlets and journalists far more resilient in the face of SLAPPs.

There is no silver bullet to the problem of SLAPPs. In every country, the situation needs to be carefully analyzed and a package of measures tailored to the country situation should be pursued. It may well be that in some countries none or only some of these short-term measures will work. For example, where the judiciary is not independent and the outcome of a trial is a foregone conclusion, cost-capping or a media insurance policy will not help. However, in many countries there is scope for introducing the tactics and strategies discussed in this report and if several of these solutions are implemented alongside one another, as a package of measures, there is no doubt that this will make news outlets and journalists far more resilient in the face of SLAPPs.

A media outlet that has had their reports vetted prior to publication by a specialist media lawyer, and that can call on insurance or a similar initiative to provide them with specialist lawyers at a low cost, is immeasurably better equipped to resist a SLAPP, or even just a letter threatening a lawsuit, than an outlet or a journalist who faces the prospect of defending the case on their own.

To enable SLAPP defendants to make use of these options, media support organizations and international donors have a role to play. In addition to advocating for legal reform, media development stakeholders can provide resources and facilitate partnerships that would allow journalists and media organizations to resist these attempts to disrupt their work.

First and foremost, news outlets, journalists, and activists should be empowered to invest in their own resilience. Strong partnerships between lawyers and journalists are crucial in the pre-publication stage as well as in the defense of any SLAPP litigation but require resourcing. To the extent that the media currently lack the means for this, donors can step in to provide that support. Crucial infrastructure mechanisms such as mutual insurance mechanisms should also be supported. In countries where insurance is not available or not accessible, legal defense funds can play a crucial role and should be supported, alongside pro bono initiatives.

Second, solidarity among media, journalists, activists, and other SLAPP victims can be game-changing. Through their combined powers, coalitions of media organizations can provide resources. They can also provide important emotional support to ease the psychological burden of defending SLAPPs. They can even be a deterrent in themselves. As the Coalition against SLAPPs in Europe has stated: “The very existence of coalitions can act as a deterrent.”57 Such solidarity is important in any country, regardless of the legal system—it is arguably even more important in countries where the political and legal system is more repressive.

Third, media development donors should support legal defense campaigns. The lawyers defending SLAPP cases are often part of a small community of lawyers willing to take public interest cases. In some countries, this can be just a handful of lawyers; in larger countries, the number can be higher. They are often willing to work pro bono, but this is not always realistically possible, particularly in countries outside of North America and Western Europe. Some donor support is therefore required. This support should extend to spaces where lawyers and journalists can exchange experiences and discuss legal developments such as the abuse of process defense outlined in the Mineral Sands example. Traditionally, such strategies were possible only in common law countries, where higher courts are comfortable with the concept of developing the law through their judgments. However, especially with the rising prominence of the European, African, and inter-American human rights mechanisms, courts in other countries are increasingly receptive to rights-based arguments, opening the door for lawyers to devise innovative strategies that defend the right to freedom of expression of the media.

Finally, the focus of anti-SLAPP campaigns should not be just on reforming defamation or similar laws. In many countries, a lot can be achieved by advocating for measures at the level of secondary legislation or court procedure, such as instituting early dismissal provisions, cost-capping cases, and broadening eligibility for legal aid requirements. Individually, none of these measures is a panacea. But as a carefully targeted package, they can do much to alleviate the burden on journalists straining under the weight of these frivolous lawsuits.

Acknowledgments

The author expresses his sincere thanks to Alinda Vermeer at Media Defence; Avani Singh and Dario Milo at Webber Wentzel; Drew Sullivan from the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project; Gill Phillips at the Guardian; and Matthew Caruana Galizia, director of the Daphne Caruana Galizia Foundation, for sharing their experiences and insights, which helped shape this paper.

Footnotes

- Donald Trump, as quoted in Paul Farhi, “What Really Gets under Trump’s Skin? A Reporter Questioning His Net Worth,” The Washington Post, March 8, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/that-time-trump-sued-over-the-size-of-hiswallet/2016/03/08/785dee3e-e4c2-11e5-b0fd-073d5930a7b7_story.html. In court, Trump lost the case comprehensively, illustrating that it was never about winning the case—it was about bringing the claim just to burden the journalist: Trump v. O’Brien, Time Warner Book Group, Inc., and Warner Books, Superior Court of New Jersey, Appellate Division, September 7, 2011.

- Penelope Canan and George W. Pring, “Strategic Lawsuits against Public Participation,” Social Problems 35, no. 5 (December 1988): 506-519.

- SLAPPed but Not Silenced: Defending Human Rights in the Face of Legal Risks (London: Business & Human Rights Resource Centre, 2022), https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/from-us/briefings/slapped-but-not-silenced-defending-human-rights-in-the-face-of-legal-risks/.

- See, for example, Shutting Out Criticism: How SLAPPs Threaten European Democracy (Coalition against SLAPPs in Europe, March 2022), https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5f2901e7c623033e2122f326/t/6231bde2b87111480858c6aa/1647427074081/CASE+Report+on+SLAPPs+in+Europe.pdf.

- Information provided by email from Media Defence Chief Executive Officer Alinda Vermeer, June 30, 2022 (on file with the author).

- Snezana Green, “SLAPPs and Legal Harassment: A Scourge that Must Be Stopped,” Media Development Investment Fund, December 3, 2021, https://www.mdif.org/slapps-and-legal-harassment-a-scourge-that-must-be-stopped/.

- As reported by, among others, the European Parliament: The Use of SLAPPs to Silence Journalists, NGOs and Civil Society, PE 694.782 (Brussels: Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs, Directorate-General for Internal Policies, European Parliament, June 2021).

- SLAPPs against Journalists across Europe: Media Freedom Rapid Response (London: ARTICLE 19, March 2022), https://www.article19.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/A19-SLAPPs-against-journalists-across-Europe-Regional-Report.pdf.

- As detailed in, among others, SLAPPs against Journalists across Europe, ARTICLE 19.

- As detailed in, for example, the European Commission working document on SLAPPs: Commission Staff Working Document, SWD (2022) 117 Final (Brussels: European Commission, April 27, 2022), https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52022SC0117&from=EN.

- Italian journalist Antonella Napoli has been defending a single defamation case for more than 20 years: Paola Rosà and Claudia Pierobon, “Croatia and Italy: The Chilling Effect of Strategic Lawsuits,” Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso Transeuropa, October 29, 2019, https://www.balcanicaucaso.org/eng/Areas/Croatia/Croatia-and-Italy-the-chilling-effect-of-strategic-lawsuits-197339.

- “Breaking the Silence: Countering the Effect of SLAPPs on Independent Media” (Washington, DC: National Endowment for Democracy, March 23, 2022). Recording of Center for International Media Assistance event on countering SLAPPs, featuring OCCRP Co-founder Drew Sullivan, among others, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DpzVZ0smjH0.

- Carmela Caruso, “How Strategic Lawsuits Are Used to Silence Journalism,” Voice of America, November 24, 2021, https://www.voanews.com/a/how-strategic-lawsuits-are-used-to-silence-journalism/6326626.html.

- “Cascade of Frivolous Lawsuits Endangers Top Serbian Investigative Journalism Outlet KRIK,” OCCRP, December 7, 2021, https://www.occrp.org/en/40-press-releases/presss-releases/15619-cascade-of-frivolous-lawsuits-endangers-top-serbian-investigative-journalism-outlet-krik.

- Susan Coughtrie and Poppy Ogier, Unsafe for Scrutiny: Examining the Pressures Faced by Journalists Uncovering Financial Crime and Corruption around the World (United Kingdom: The Foreign Policy Centre, November 2020), https://fpc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Unsafe-for-Scrutiny-November-2020.pdf.

- For example, Polish newspaper Gazeta Wyborcza and Guatemalan newspaper El Periodico are each defending several dozen cases (referenced by Snezana Green, note 6); Brazilian journalist João Paulo Cuenca is defending more than 140 lawsuits filed all over the country by pastors from a church that he tweeted about (as reported by Media Defence: “Over 140 Lawsuits Filed against Journalist João Paulo Cuenca in Brazil,” Media Defence, February 26, 2021, https://www.mediadefence.org/news/over-140-lawsuits-filed-against-journalist-joao-paulo-cuenca-in-brazil/); Cameroonian journalist Nestor Nga Etoga has made nearly 100 court appearances since 2016, spent US$35,400 on legal fees, and had to close his media outlet, as reported by the Global Investigative Journalism Network: Jared Schroeder, “SLAPP Fight: How Journalists Are Pushing Back on Nuisance Lawsuits,” Global Investigative Journalism Network, September 14, 2021, https://gijn.org/2021/09/14/slapp-fight/.

- Although there are successful examples, crowdfunding is not feasible in most cases and so is not discussed here.

- As announced in “Reinventing the Playbook to Strengthen Global Democracy,” US Agency for International Development, June 2022, https://www.usaid.gov/news-information/press-releases/jun-7-2022-administrator-power-calls-reinventing-playbook-strengthen.

- Marigo Farr, “Launching a Legal Defense Fund for Journalists,” Nieman Reports, December 12, 2022, https://niemanreports.org/articles/slappoccrp-drew-sullivan/.

- See, for example, Best Practices Guide to Setting Up a Legal Defense Fund (US National Lawyers Guild, July 2018), https://www.nlg.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/NBFN-NLG-Legal-Defense-Fund-Guide-FINAL.pdf.

- See the website for the Legal Network for Journalists at Risk at https://www.medialegalhelp.org/, accessed September 23, 2022.

- See “What We Do,” Media Defence, n.d., https://www.mediadefence.org/what-we-do/, accessed November 23, 2022.

- Some law firms—for example, the UK law firm Reviewed & Cleared (https://reviewedandcleared.com/)—specialize in this work.

- See “Pre-publication Review,” Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, n.d., https://www.rcfp.org/pre-publication-review/, accessed September 23, 2022; the website for Vaša prava BiH at https://pravnapomoc.app/ba, accessed September 23, 2022; and the website for the Daphne Caruana Galizia Foundation at https://www.daphne.foundation/en/, accessed September 23, 2022.

- See “About FELN,” Free Expression Legal Network, n.d., https://freeexpression.law/about-feln/, accessed September 23, 2022.

- “Freedom of Speech of Expression Center,” Center for the Protection of Freedom of Expression, n.d., http://hnd.hr/eng/freedom-of-speech-of-expression-center1, accessed October 26, 2022.

- For example, through the shared services resource center set up between investigative journalism centers in Southern Africa. See the website for IJ Hub at https://ijhub.org, accessed September 23, 2022.

- Mineral Sands Resources (Pty) Ltd and Others v Reddell and Others (2022) ZACC 37, paras. 94-95.

- Ibid., par. 100.

- Jameel & Ors v. Wall Street Journal Europe Sprl, October 11, 2006, (2006) UKHL 44, par. 158.

- As described in Peter Noorlander, “International, Regional, and National Approaches to the Protection of Reputation and Freedom of Expression,” in Regardless of Frontiers: Global Freedom of Expression in a Troubled World, ed. Agnes Callamard and Lee Bollinger (New York: Columbia University Press, 2021).

- As per 2019 Learning Report (London: Media Defence, 2020), https://www.mediadefence.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/2019-learning-report-FINAL.pdf. The direct impact of the judgment on cases has been tracked by Columbia University’s Global Freedom of Expression Program. See “Lohé Issa Konaté v. The Republic of Burkina Faso,” Global Freedom of Expression Program, Columbia University, n.d., https://globalfreedomofexpression.columbia.edu/cases/lohe-issa-konate-v-the-republic-of-burkina-faso/, accessed November 23, 2022.

- “Time to Take Action against SLAPPs,” Council of Europe, October 27, 2020, https://www.coe.int/en/web/commissioner/-/time-to-take-action-against-slapps.

- OOO Memo v. Russia, Application no. 2840/10, March 15, 2022. The judgment is considered a key case in the hierarchy of the court’s case law.

- The work of the fund along with some of its beneficiaries is described here: “Global Media Defence Fund,” UNESCO, n.d., https://en.unesco.org/global-media-defence-fund, accessed September 26, 2022.

- For example, Columbia University’s Global Freedom of Expression Project, which includes a case database with comment and analysis and organizes regular conferences. See the project’s website at https://globalfreedomofexpression.columbia.edu/, accessed September 26, 2022.

- UNESCO announces 2022 Call for Partnerships of the Global Media Defence Fund, https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/unesco-announces-2022-call-partnerships-global-media-defence-fund, accessed November 23, 2022.

- Barış Altıntaş, “SLAPP Lawsuits: Power vs. Pen, Justice for Journalists,” March 7, 2022, https://jfj.fund/slapp-lawsuits-power-vs-pen/.

- See “Conduct in Disputes,” Solicitors Regulation Authority, March 4, 2022, https://www.sra.org.uk/solicitors/guidance/conduct-disputes/.

- See the Media Law Resource Center’s website at https://medialaw.org/why-join-mlrc/, accessed September 23, 2022.

- “Henley and Partners Threatens Legal Action against The Shift,” The Shift, December 24, 2017, https://theshiftnews.com/2017/12/24/henley-and-partners-threatens-legal-action-against-the-shift/; “No Threatening Letters Can Stop Daily Maverick from Reporting the Truth,” Daily Maverick, August 20, 2021, https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-08-10-no-threatening-letters-can-stop-daily-maverick-from-reporting-the-truth/.

- As quoted in “Slapped Down: Six Journalists on the Legal Efforts to Silence Them,” Index on Censorship, December 2, 2020, https://www.indexoncensorship.org/campaigns/slapped_down_report_efforts_to_silence_journalists/.

- See “About Us,” Asina Loyiko, n.d., https://asinaloyiko.org.za/about, accessed September 23, 2022.

- See the website for the Coalition against SLAPPs in Europe at https://www.the-case.eu/, accessed September 23, 2022, and the website for Protect the Protest at https://protecttheprotest.org/, accessed September 23, 2022.

- The Business & Human Rights Resource Centre has made the same recommendation in the context of SLAPPs against human rights defenders in Southeast Asia: See Strategic Lawsuits against Public Participation: Southeast Asia Cases & Recommendations for Governments, Businesses, & Civil Society (London: Business & Human Rights Resource Centre, March 2020), https://media.business-humanrights.org/media/documents/SLAPPs_in_SEA_2020_Final_TRddA8a.pdf.

- Note 33, paragraph 18.

- “Law No. 08/L-035 on Amending and Supplementing Law No. 04/L-017 for Free Legal Assistance,” Official Gazette of the Republic of Kosovo, no. 8 (February 25, 2022).

- In the context of Southeast Asia, it has been remarked that legal aid is rarely sufficient. See Strategic Lawsuits against Public Participation, Business & Human Rights Resource Centre, 8.

- See, for example, the relevant codes in New York, Washington, Minnesota, Ontario, and British Columbia, as discussed in Nikhil Dutta, Protecting Activists from Abusive Litigation: SLAPPs in the Global South and How to Respond (International Center for Not-for-Profit Law, July 2020), https://www.icnl.org/wp-content/uploads/SLAPPs-in-the-Global-South-vf.pdf, 20-23.

- “Crackdown on Corrupt Elites Abusing UK Legal System to Silence Critics,” UK Ministry of Justice, July 20, 2022, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/crackdown-on-corrupt-elites-abusing-uk-legal-system-to-silence-critics.

- Rules of Procedure for Environmental Cases, A.M. No. 09-6-8-SC, Rule 6, https://www.lawphil.net/courts/supreme/am/am_09-6-8-sc_2010.html. The accompanying rationale, a 58-page document that includes a substantial chapter on SLAPPs, is also worth reading. See Rationale to the Rules of Procedure for Environmental Cases (Manila: Philippine Judicial Academy, 2010), https://philja.judiciary.gov.ph/files/learning_materials/A.m.No.09-6-8-SC_rationale.pdf.

- Dutta, Protecting Activists from Abusive Litigation.

- Thailand Code of Criminal Procedure, Articles 161/1 and 165/2.

- “Crackdown on Corrupt Elites Abusing UK Legal System to Silence Critics,” UK Ministry of Justice.

- Robert Sharp, “Malkiewicz v United Kingdom: Time for the County Courts to Hear Defamation Cases?” International Forum for Responsible Media Blog, December 14, 2021, https://inforrm.org/2021/12/14/malkiewicz-v-united-kingdom-time-for-the-county-courts-to-hear-defamation-cases-robert-sharp/.

- A number of examples are summarized in Dutta, Protecting Activists from Abusive Litigation, 20-23.

- Shutting Out Criticism: How SLAPPs Threaten European Democracy (Coalition against SLAPPs in Europe, March 2022), https://www.the-case.eu/s/CASE-report-SLAPPs-Europe.pdf.