Key Findings

In 1995, the international community enacted the “Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action,” a watershed UN resolution affirming the global commitment to gender equality. Yet, nearly three decades later, gender inequality remains an intractable problem in the media sector. Women journalists are outnumbered by their male counterparts, and few women break through the glass ceiling to management positions. Pay inequality and harassment of women journalists is pervasive around the world. And, advertisers, funders, and policymakers seldom analyze the media enabling environment in the context of gender equality, which limits the development of systemic solutions.

Genuine transformation will require unified efforts at all levels of the media ecosystem—from local grassroots initiatives to robust international regulatory frameworks. As a valuable resource for the media development community, students and scholars of journalism and communications, and the media industry, this study offers insights that can inspire action to combat gender inequality and promote more inclusive media practices.

-To enhance gender equality, newsrooms must provide resources, support, and accountability mechanisms that enable women journalists to reach leadership positions and address workplace grievances.

-Funding for gender equality in media development is severely lacking. When designing and implementing strategies to advance and safeguard independent journalism, donors, policymakers, and businesses must integrate a gender lens, and monitor progress against gender equality indicators.

-Local, regional, and international actors must spearhead a coordinated movement for gender equality at normative, policy, and implementation levels. A key facet of this will be leveraging regulatory and self-regulatory mechanisms to protect women journalists and enhance gender inclusion in media while safeguarding editorial autonomy and media freedom.

Introduction

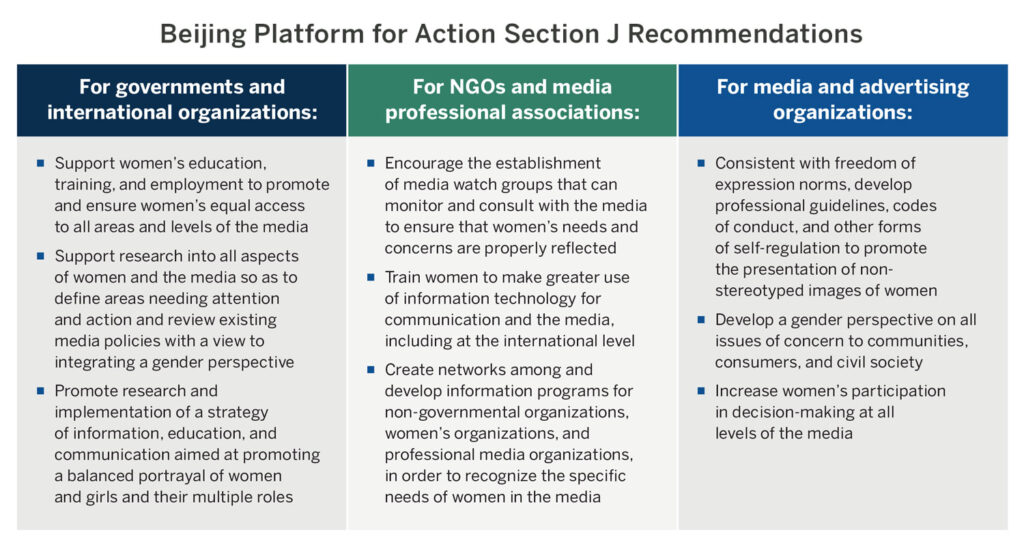

In 1995, the Beijing Platform for Action—the most comprehensive blueprint for closing the gender gap in news media—was adopted unanimously by 189 countries at the United Nation’s Fourth World Conference on Women. Yet, despite these international commitments, advancing gender equality in the media sector has been slow. While progress has been made, it has been piecemeal. More needs to be done: a systemic approach across sectors and levels of society is needed to move the needle in the struggle for gender equality in news and information systems.

News play a critical role in shaping societal attitudes toward gender equality, whether by spotlighting persistent inequalities and pushing for change, or by reinforcing existing biases. While the international development community often emphasizes media as an important tool for advancing gender equality, as laid out in the Beijing Platform for Action and other transnational policy frameworks, more work needs to be done to advance gender equality within the journalism sector itself.

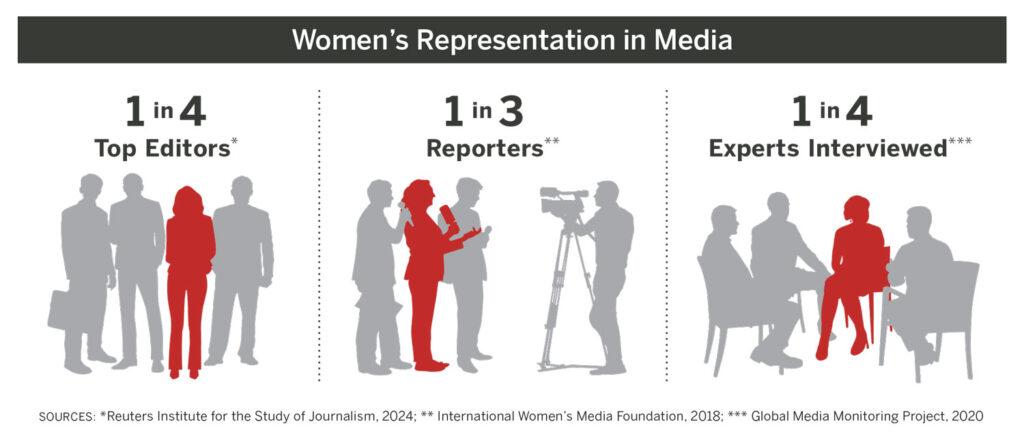

Male journalists outnumber women journalists in most countries. Globally, women are largely shut out of newsroom leadership, making up only about a quarter of top management positions.1 In news content, women constitute only a quarter of sources and subjects in news stories across traditional media around the world. 2 Without women in top jobs to advocate for junior staff, women are unlikely to feel welcome in the profession. Without women journalists, fewer women’s stories will be told. Without a meaningful voice in news coverage, women will not be able to fully participate in public life or exert pressure on their representatives to address the challenges they face in society.3

Newsrooms often lack policies to protect their women employees from the risks they face on the job. Women in many countries face cultural barriers to working as journalists, and these patriarchal attitudes oftentimes seep into the media workplace and newsrooms. National gender equality policies are rarely applied in the media sector and the self-regulatory sphere doesn’t appear to have a well-developed set of norms and standards when it comes to ensuring gender equality in the news media.

The sheer lack of data tracking the sector’s performance on gender equality drives home the urgent need for more meaningful commitments to address this issue. The gender dynamics of the media industry should not be a niche issue. Women’s representation in the public eye, women’s access to the information they need for everyday life, women’s ability to tell their own stories—these are all key considerations in promoting good governance. Yet, there is a lack of consistent global data on the gender distribution of newsroom staff and the number of women who own or manage media outlets. The Global Media Monitoring Project, which looks at gender representation in news content and is updated every five years, is an excellent start, but more data are needed on gender equality indicators in news production. Without having all the relevant data at hand, it is no surprise that progress on gender equality in news media has not advanced as much as it has in other professional sectors.4

A global study by the Fojo Media Institute found that international agreements and national policies committing countries to advancing gender equality rarely manifest in regulations governing the media sector. National policymaking in the media sector must find a balance between enacting regulation and upholding respect for media freedom and independence. Moreover, due to the potential risks of government interference in editorial decision-making, national policy is often not the appropriate mechanism for regulating gender equality goals in media content or media business. To that end, co-regulatory and self-regulatory models are necessary to push for the development of a more equitable media environment.5

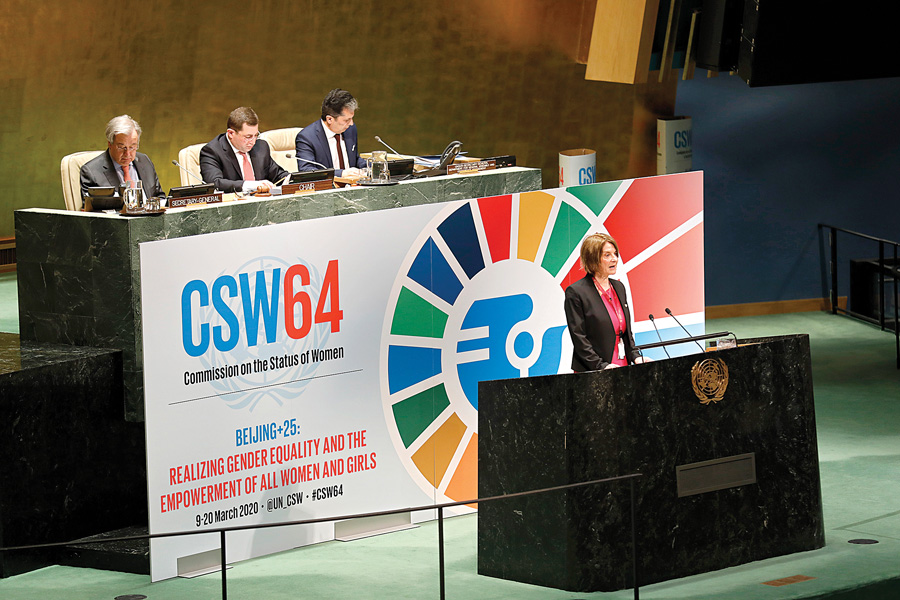

High-level panel discussion commemorating the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action. © Flickr / UN Photo/Antoine Tardy / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Media can be a powerful force for social change or a reinforcer of oppressive societal norms. To advance gender equality in the media, media development organizations, civil society, and governments must look beyond the operations of individual news outlets and focus on the enabling environment. The pursuit of gender equality must be systemic, such that it becomes the norm across all outlets, not only an exceptional few.

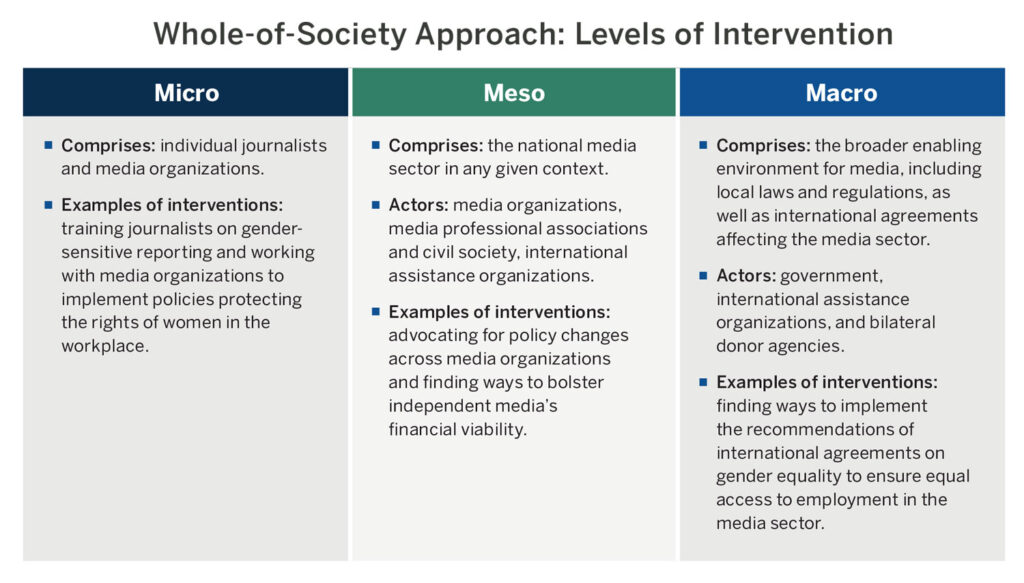

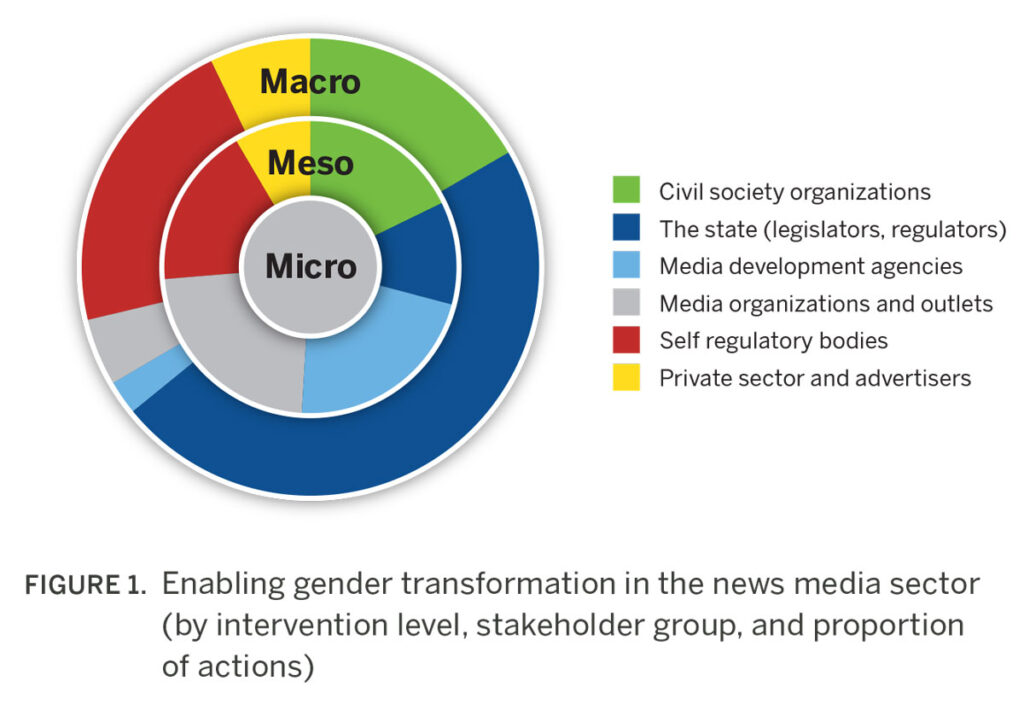

Meaningful change requires a whole-of-society approach that involves concerted effort from actors at all levels—micro, meso, and macro—including media outlets, civil society, media support organizations, governments, and the international assistance community that supports journalism. This paper reviews the status of gender equality in journalism across these levels, including through three case studies, and provides recommendations for how a gender-equal news media can be achieved.

To identify effective entry points for the development and advancement of independent gender-equal media systems, Fojo and the Center for International Media Assistance (CIMA) hosted workshops bringing together journalists, academics, media regulators, and civil society actors from around the world. The workshops focused on gender equality as it relates to three areas of media development: media ownership and management, media regulation, and media market dynamics.

The Micro Level: Media Ownership and Management

Within the news industry, media outlets and civil society organizations that support media have made insufficient progress with respect to advancing gender equality. The media sector remains a hostile profession for women journalists in many countries.6

Women’s representation in media will not see significant improvement until women are better represented in editorial leadership and newsroom management, and more outlets with women owners are able to survive and attract funding. Training more women journalists means little if the sector fails to retain their talent because, in addition to facing violence and harassment for working in a male-dominated field, they must contend with a glass ceiling that prevents them from reaching decision-making roles, regardless of their efforts and abilities.

A 2023 study by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism found that women make up just 22 percent of editors in leadership roles across 12 markets spanning five continents. This marks a mere 1 percent increase from 2022.7 Efforts to meaningfully improve these numbers will require more than offering to train more women journalists. To ease the way for women seeking to advance in journalistic careers, the evidence points to several promising interventions: capital investments for news startups founded by women, the adoption and implementation of equal opportunity policies in established outlets, and advocacy by journalist unions for the protection of women’s rights in the workplace.

Creating pathways with which women could ascend to leadership roles could significantly impact the journalism sector. For one, it could affect news outlets’ ability to hire and retain women. Few media outlets have policies that accommodate the needs of women employees or ensure they have the same access to career advancement opportunities as their male counterparts.8 In many contexts, women are expected to pull double duty, not only working full time but also shouldering most of the housework and child rearing responsibilities. In addition, women journalists often face harassment internally within organizations and externally in the broader environment over the course of their work, not only from managers and colleagues but also from sources.9

Newsrooms need to implement policies that provide mechanisms for redress in cases of sexual harassment. Additionally, newsrooms must establish reporting mechanisms for issues like online harassment or violent threats from potential sources or from audiences—problems that affect all journalists, but disproportionately women. In some contexts, press unions, civil society, and media support organizations should advocate for fundamental rights for women in the workplace and address unspoken biases that affect career opportunities for women journalists.

“Women are often assigned to do soft news. And later, they are considered as not good enough for leadership,” said Ethiopian journalist Melkamsew Solomon. “Media is a very serious thing. Hence, it is unthinkable to give such a big responsibility to women.”10

If news organizations are truly committed to gender equality, they need to have policies in place to ensure that women are hired and retained by creating a safe environment to work in and providing pathways to career advancement. Women must have equal access to training, receive equal wages, and be considered for promotions. This commitment must come from leadership.

News outlets that do not reflect the demographics of the societies they are meant to serve are limited in the type of content they are able to produce and audiences they can attract. A gender-equal editorial team is more likely to produce content that appeals to women and men audiences and to cover a broad range of topics that interest diverse audience segments.

In some cases, journalists have trouble getting editors’ approval to cover stories focused on women. In many newsrooms across Africa, all-male editorial teams often reject pitches from women journalists for stories they perceive to be “women’s issues.”11 While funding women journalists to report on issues that affect women in their communities is important, overemphasizing the gender dimensions of certain stories risks siloing them as women’s issues. Men also need to be trained to apply a gender lens to their reporting, and this perspective should be mainstreamed across the various topics a given outlet covers.12

The Global Media Monitoring Project’s findings from South Africa suggest a link between newsroom leadership and content. South African mainstream news media have significantly outperformed on gender equality indicators in content compared with the rest of the world, strongly correlating to near gender parity in media leadership.13

However, ensuring women are able to hold leadership positions in news outlets is not a stand-alone measure. Support systems are needed to mentor young women entering the field and to monitor progress on gender equality goals. Journalist unions have an important role to play in advocating for better working conditions for women in the sector and setting standards for responsible journalism by holding journalists accountable to codes of ethics.

Research looking at women’s representation in journalist trade unions in 13 countries found that countries with higher levels of women in journalist unions also had higher rates of women in leadership positions in news organizations.14

© Flickr / UN Women / Ryan Brown / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Unfortunately, data are distinctly lacking both on union membership by gender in many countries and the degree to which union membership can be linked to material improvements in working conditions for women journalists. Recent research suggests that women are underrepresented in both union leadership and membership in the Middle East and North Africa15 and Asia-Pacific regions.16 Some unions are taking steps to remedy this issue. For example, the Sierra Leone Association of Journalists (SLAJ) adopted a Media Gender Equality Policy that sets goals for improving gender equality in newsrooms through a monitoring program and the implementation of safety measures and parental leave policies. It also mandates that women constitute at least 30 percent of the executive members of SLAJ’s board.17

Boosting the number of women in journalist unions cannot move the needle on its own. In Europe, where women have achieved near parity in union leadership—and even surpass men in some countries— women journalists continue to face lingering issues of unequal treatment, including persistent pay gaps.18Unions need to work with civil society and women’s movements to push for newsroom policies that protect women’s interests. The progress made in South Africa, for example, emerged in part from the efforts of groups like Gender Links to hold media companies to account for their responsibility to abide by the Southern African Development Community’s policy agreements regarding gender equality in employment practices and media content.19 The fact that Gender Links’s work attracted support from a number of bilateral donors, including the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, the European Union (EU), and the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO),20 also underscores the important role of the international development community in keeping these types of media advocacy organizations alive as they work to enact meaningful change for the sector.

While there is much that still needs to be done to get more women into top jobs in the news industry, there are signs that the digital media landscape has created new opportunities for women journalists seeking to break away from the constraints of traditional media organizations. Research from SembraMedia on “digital native”21 news outlets in 12 countries found that 32 percent of all founders across the 201 companies in the study were women.22 Project Oasis, which looked at media outlets that were founded in Europe and exist only online, had similar findings: 46 percent of the over 500 organizations in their directory had at least one woman founder, and women made up 58 percent of all the founders featured in the project’s report. Project Oasis also found that organizations with male and female founders often generate more revenue than those with only male founders—€509,740 (around $550,000) in average annual gross revenue compared to €497,719 (around $536,000). While this suggests that diverse leadership can lead to improved revenue generation, the research also found that outlets with only women founders had drastically less revenue than either of the other categories: on average, €101,135 ($109,000). Possible explanations for this glaring disparity include a lack of women in decision-making roles among investors and higher levels of risk aversion toward women-led companies.23

Despite the challenges women entrepreneurs face in attracting funding, evidence from other sectors suggests a strong business case for pursuing gender equality in news media. An analysis of companies based in China and the United Kingdom (UK) encompassing a variety of sectors found a positive relationship between a gender diverse leadership and organizational innovation, with implications for firm performance and revenue.24 A 2018 analysis of data on 394 French firms spanning 10 years found a positive relationship between return on assets and equity and women directorship. When the model is controlled for attributes of women directors such as education, it yields a positive trend between market-based performance (market expectations about a firm’s further earnings) and women directorship.25 The results are consistent with numerous other studies. In Vietnam, gender diversity on boards is linked to positive company performance.26 Similarly, in Mauritius, a significant relationship exists between board diversity in publicly listed companies and short-term financial performance.27 That these studies covered a diversity of sectors—such as banking, tech, and pharmaceuticals—suggests that the relationship between company leadership and financial performance should hold true for news media companies as well.

An emerging body of evidence indicates that taking steps to cultivate women audiences would improve news outlets’ financial health. Recent research reveals how gender gaps affect the bottom line of media organizations. One study of 1,700 news providers in the United Kingdom, United States, India, China, South Africa, Kenya, and Nigeria found that men consume more news than women—both digitally and offline.28Although it may not be possible to fully close the gap, research shows that working toward that goal is in the best financial interest of news outlets around the world. Reducing the disparity by one percentage point per year starting in 2023 promises additional global revenue of $11 billion over five years and $38 billion over 10 years for the news industry.29 Cultivating the growth of women audience segments through a holistic marketing strategy would help the business side of media, in view of the social-cultural barriers and economic inequalities facing women.

Women are considered a high-value audience sector for advertisers globally. Yet, neither audiences nor advertisers will simply flock to media outlets that produce content aimed at women. To build an audience, news outlets need to develop content and marketing strategies informed by market research that respond to the needs of their target segments.30

© African Women in Media / Toun Akewale Sonaiya, Women Radio FM, Nigeria, and more

Some independent media outlets have developed new revenue streams by leveraging their brand’s reputation with regard to gender equality and collaborating with funders and advertisers. In Latin America, for instance, digital independent media supported by SembraMedia attract resources from local and international funders to support gender-oriented campaigns and produce content related to commemorative dates on human rights. Linking content to human rights days is a common strategy. A major regional, independent media organization that conducts data-driven journalism across seven countries in Africa carries content to support International Women’s Day (March 8)—not because of a new disposition toward supporting gender equality, but because publishing such content is a magnet for donor funding.31 Similarly, some news organizations in Latin America are paid to hold gender equality workshops for journalists and advertisers.32 Rappler in the Philippines and GK in Ecuador have branded content arms that work with advertisers interested in marketing products to women or highlighting social causes like gender equality to produce content aimed at women audiences.33

While the pursuit of profitability should not be the sole motivating factor for promoting gender-equal news media, it is nevertheless an important incentive for a sector that has long proven resistant to change.

CASE STUDY 1

The Financial Sustainability of Feminist News Initiatives: Khabar Lahariya and Alharaca

Though gender equality is an important consideration for all news outlets, some news organizations have found a niche by adhering to a feminist approach in their content and organizational structures. Khabar Lahariya in India and Alharaca in El Salvador are two feminist outlets carving out a space for themselves in their markets by leveraging their feminist identities to create unique content, engage with underserved audiences, and develop sustainable business models.

For both outlets, feminism is an underpinning principle that was baked into their founding. As Laura Aguirre, founder and executive director of Alharaca, noted, representing a gender perspective in content is different from operating according to feminist organizing principles.34

Khabar Lahariya grew out of a literacy project for women over 20 years ago. Empowered by the project, a group of Dalit and Adivasi women35 started producing news for underrepresented communities, including caste-oppressed groups, religious minorities, and women. Under the umbrella of an Indian NGO (Nirantar), they built a news channel that started with a printed newsletter and gradually added other formats before turning digital in 2017. All content is written, edited, produced, distributed, marketed, and managed by rural women from disadvantaged communities.

Donor funding has been crucial for both Khabar Lahariya and Alharaca. These funds are critical for the continued existence of these types of feminist news initiatives; however, it can also be difficult to rely upon donor funding, as shifts in donor priorities can result in devastating losses of funding for smaller outlets. As Aguirre pointed out, many donors are currently focused on El Salvador, which makes it easier to attract funding, but it is important to plan for a possible change in circumstances.

Unpredictable though donor funding may be, finding viable alternative revenue streams can be a challenge. Khabar Lahariya has the trust and engagement of its primary audience, but individuals in this segment do not have the means to pay for news. Additionally, since there is a massive flow of free news and information, the business case for subscription is low. Why should lower income people pay for news when they can get it for free?

With incomes in El Salvador being very low relative to the cost of living, Alharaca also found that very few people would be willing to pay for independent media. In addition, its website cannot host programmatic advertising, and it lacks the staff capacity to engage with advertisers, further limiting monetization options.

For both outlets, leveraging their local expertise into products that appeal to international audiences has been key to creating new funding opportunities that support the public service journalism they provide local audiences.

Alharaca found that specialized journalism projects opened the door to new revenue streams. Following the success of Ciudad Perdida (Lost City), an urban memory podcast chronicling the events that took place during the funeral of Monsignor Óscar Arnulfo Romero in 1980, the outlet adapted the podcast into an audio walking tour, which was well-received by donors. The project brought in a new form of income, as international organizations and foreign dignitaries paid Alharaca to host walking tours for them. The outlet now aims to create journalistic products that can be scaled up in this way.

Khabar Lahariya discovered an untapped market segment. While providing underrepresented people with news for free, Khabar Lahariya developed an English- language subscription service, KL Hatke, aimed at an urban Indian and international audiences who were looking for lesser-told and nuanced narratives from rural India on topics including development, the impact and implementation of policies and schemes, feminism, gender-based violence, caste, and the everyday lives of people. Subscribers get access to unique materials such as graphic narratives, premium articles, workshops and talks with the women of KL, and exclusive newsletters. The income from these audiences provides a financial foundation for the outlet, which also relies on for-profit partnerships with other newsrooms and NGOs.

As Laura Aguirre explained, “We want to grow together, not alone.” 36 As both outlets strive for financial independence, their feminist principles also motivate them to work with others to build skills and share resources. Khabar Lahariya trains women from other rural areas, places rarely covered by mainstream media, to become journalists and cover issues that affect their communities. Alharaca works with other journalists and news outlets to form small teams that can create a collaborative news product. These collaborations are a priority for Alharaca, both as a chance to share resources and a way to counter the stereotypical image of journalists as lone men.

The Meso Level: Media Market Dynamics

Despite the evidence that financial incentives improve gender equality in news media, surface-level change in pursuit of profit is unlikely to provide a solution to the sector’s growing financial crisis. To be clear, even when it does not translate into immediate opportunities for profit, gender equality should remain a central tenet of media development. True sectoral change requires an inclusive approach, bringing in partners from civil society, social movements, and international development actors.

Media do not exist in a vacuum. If the market is not capable of supporting independent media, whether due to a weak advertising industry or media capture by the state or private actors, advocates need to focus on improving the enabling environment for media markets, rather than changing the modes of operation of news outlets themselves.

The business model for news media in many African countries is broken. In many countries, journalists are paid through bribes, and journalism doesn’t receive much revenue from audiences or advertisers.37 In those cases, some news outlets have no reason to concern themselves with the interests of their audiences, only those of their benefactors, which, in patriarchal societies, are likely to be men.38

Meanwhile, in Ukraine, the Russian invasion caused the advertising industry to collapse. As a result, many media outlets that had once achieved financial sustainability now find themselves heavily reliant on donor funding. For example, Divoche.media, a Ukrainian outlet focusing on gender and LGBTQI+ issues that prides itself on its independence from big—and often oligarch-controlled—media conglomerates, relied mainly on advertising as its main source of revenue prior to the outbreak of COVID and the war. However, it is currently funded primarily by grants since the market is struggling. Despite this change in market conditions, the magazine’s readership has grown since the start of the war.39

Divoche.media’s case demonstrates the importance of donor funding in supporting gender equality in the media sector and keeping feminist media initiatives afloat when market conditions would not otherwise allow them to survive. In some cases, donor funding also helps outlets take on special projects related to gender equality that they could not have otherwise afforded. The Mexican feminist news service Comunicación e Información de la Mujer (CIMAC), for instance, has managed to diversify its revenue streams, conduct training, monitor content from a gender perspective, and carry out campaigns in collaboration with partners. It does, however, rely on donor funding for its work monitoring the safety of women journalists.

Short-term, project-based funding to produce media content or train women journalists can only go so far. If more women are trained as journalists but news outlets won’t hire them because their editorial teams do not see the value of representing women’s perspectives, then little has been achieved. To facilitate lasting change, donors must work with local partners to develop strategies for strengthening media markets as a whole, while mainstreaming gender within those efforts rather than siloing gender equality as a separate issue area.

International assistance actors are taking some interest in meaningfully mainstreaming gender in their work, but there is still room for improvement. While most international development organizations have a gender strategy that stresses gender mainstreaming across all programs—from the design phase through monitoring and evaluation—the degree to which this is consistently applied is unclear. Whether and how gender mainstreaming approaches are uniquely tailored to media assistance projects is also unclear.

Although development organizations that have media programs emphasize the importance of gender equality, they often take an instrumentalist view of the media, focusing on its role in combating gender-based violence, for example, or keeping women informed of their rights. More research is needed to determine the impact of both targeted initiatives to promote gender equality in media and gender mainstreaming in media development programs.

News outlets seeking funding are generally aware that gender equality is a priority area for donors. As a result, donor-dependent outlets tend to make gestures toward gender equality to attract funding. Unfortunately, these changes are often only skin-deep, such as providing special coverage on International Women’s Day. While donor support for independent media, particularly feminist media, in contexts where the market cannot sustain them is invaluable, focusing interventions on media outlets is not enough. Donors need to support standard-setting organizations like press associations and civil society organizations that are advocating for broader change and monitoring policy implementation.

Even initiatives focused on improving gender equality in news content and news outlets’ organizational structures, like the UN Women Media Compact, tend to concentrate on changing individual news outlets.40 As crucial as those commitments are, the persistence of the gender gaps in the media sector—across news content, consumption, and production—suggests that there are root causes for these imbalances that need to be strategically addressed. International assistance actors can help formulate frameworks for gender-equal media support that examine not only the performance of news outlets and media support organizations, but the other forces at play that can incentivize or hinder media from meeting those goals. Can the advertising market support independent media? If so, are advertisers demonstrating an interest in reaching women audiences? If not, what other sources of local funding are there and what are the implications for gender equality? Are there social reasons why women might have difficulty working as journalists? Are there policies in place to protect the rights of women in the workplace and are there organizations monitoring whether media outlets are implementing these policies?

The lack of funding for media support organizations can have a real impact. In Somalia, the Somali Women Journalists Organization has had success securing long-term support from various donors as they campaigned for newsrooms to adopt maternity leave policies.41 At the same time, another media support organization, the Somali Media Women Association (SOMWA), has struggled to offer training and legal support to women journalists due to a lack of funding and has had to shut down multiple times due to threats from militant groups.42

“At the moment, when a case of abuse happens, the only thing we can help our colleague with is emotional support. We can’t offer her legal support,” said Maryan Seylac, the founder and executive director of SOMWA, stressing the need for more international support.43

While donors are taking more of an interest in mainstreaming gender equality within media support, current efforts remain piecemeal rather than strategically motivated. Rather than gender equality being a core principle of media assistance, it is often viewed as a positive externality—it is great if it happens, but not the main goal of most projects. With several countries that are developing or have recently implemented feminist foreign policies, this growing diplomatic interest in advancing gender equality might prove to be a window of opportunity for media development.

The deepening financial crisis for media means that identifying sustainable business models for journalism is a priority for donors. Although definitions of media viability tend to vary across organizations, most stress the need for gender equality in media as a significant factor and are developing indicators to monitor the progress of those goals.

The International Fund for Public Interest Media (IFPIM) tracks gender equality indicators among the news outlets it funds, taking into account their content, newsroom structures, and leadership. Since IFPIM considers improving gender and diversity outcomes in media a priority, it supports outlets whose operational goals include improving their performance on those indicators.44

Similarly, in developing the Media Viability Accelerator—a web-based platform that provides news outlets with market insights to better inform their business strategies—Internews and its media partners have integrated gender equality in the platform’s analysis of media outlets’ performance across various indicators. Internews also plans to develop a pilot project to identify news outlets that prioritize gender inclusivity and building women audiences as part of its “Ads for News” program, which creates inclusion lists for advertisers seeking to support trustworthy news media. The challenge in using a whitelisting approach is striking the right balance between incentivizing news outlets to improve gender equality in their content without excluding too many news organizations.45

© Flickr / UN Women / Ryan Brown / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Gender equality is increasingly prioritized among donor agencies as well, with some countries adopting feminist foreign policies and feminist international assistance policies. After Sweden paved the way in 2014 with its now defunct feminist international assistance policy, Canada followed suit in 2017. Several countries have since adopted or announced a commitment to adopt feminist foreign policies, including Mexico, Chile, Colombia, and Liberia.46 While these policies include commitments to improve gender equality within institutions, as well as in various sectors in aid-recipient countries, gender-equal media development is rarely discussed as a priority in these initiatives.

Many feminist foreign policies prioritize improving gender equality in society at large, with a particular focus on certain issue areas, such as women’s political participation and including women in the decision- making processes on climate change or peace and security.47

For instance, to measure the implementation of its feminist international assistance policy, Canada lists a number of indicators, including improvements in health, education, and governance outcomes for women—with no direct mention of media.48

Despite the lack of focus on media in these agendas, this approach to international assistance provides an opportunity to prioritize gender equality within aid and assistance that supports independent journalism. Improving women’s representation within ministries and international assistance agencies—which is a goal for many of these policies—is a first step toward mainstreaming gender across aspects of development. These policies are also backed by funding commitments to projects that include gender equality as a primary or secondary goal. For example, Germany’s new feminist foreign policy includes a commitment to allocate 85 percent of aid funding to projects that include gender equality as a secondary goal, and 8 percent to projects that set gender equality as their main goal, by 2025.49

Media’s lack of inclusion among the indicators and outcomes of feminist foreign policies underscores the need for more attention to media development. Despite media’s utility in advancing other development goals, investment in media systems tends to be limited. Media assistance represents only 0.3 percent of total official development aid.50 For feminist foreign policies to have a noticeable impact on media systems, media itself would first need to become a bigger priority for donor agencies.

One of the key lessons from the experiences of these donors and media outlets is that gender gaps will not close through the efforts of journalists alone. Supporting a constellation of standard setters and women-oriented news media is necessary and important to keep gender-sensitive coverage alive where the market might fail to support it, and to provide a model for other outlets seeking to improve gender equality in their content and internal structures. However, it is not enough for truly transformative change.

The first step toward developing a strategic vision for gender equality in news systems is consistent monitoring and evaluation of gender equality indicators in news outlets, the media, and advertising markets, and the social and political dynamics of gender equality as they pertain to journalism. International assistance actors aiming to improve gender equality need to work with media experts, journalists, and media-based civil society to determine the context- specific pain points within the media sector and the wider political and cultural domains of a country, and identify potential allies among women’s rights groups, market regulatory authorities, and government agencies that can help advance a gender transformative vision for the media.

Case Study 2

SVT Sport—A Public Broadcaster and Leader in Gender-Equal Sports Coverage

Following government regulation mandating that all public service broadcasts reflect gender equality and diversity, Sweden’s SVT Sport became a pathbreaker in integrating gender equality in its news coverage and business model. This led to several competitive advantages, including more unique stories, an increase in live broadcasting, and a growing audience. SVT’s pioneering tactic of carrying more international women’s sports coverage also impacted market dynamics.

SVT Sport set its first gender-related production goal in 2014. Though gender equality is not mentioned in the Swedish Fundamental Law on Freedom of Expression, the government renewed the Broadcasting Permits, which stipulate that public broadcasters integrate a “gender equality and diversity perspective” in their programming.51 Patric Hamsch, who was SVT’s head of digital and sports news at that time, recalls how the work started: “We set the first target to 25 percent females featured in the coverage. More resources were allocated to cover women’s sports and the editors were tasked to count heads. We soon increased our ambition to 50/50 and in 2017 this goal was reached.”52

Since then, the overall gender balance has remained, despite yearly fluctuations based on major sports events dominated by one sex or the other. Hamsch again: “In 2014, when I was in London to meet with a major commercial sport news provider and I asked for more coverage of women soccer games, I got the response that no other actors were interested in this, only SVT Sport. Today this is a global trend and women sports are commercially viable. News agencies are scouting for more of women sports, to respond to the great demand from the public.”53

Through continually measuring content output, gradually increasing news and live events coverage, and telling stories from angles and perspectives never told in the world of sports journalism, SVT Sport has made women’s sports more visible to wider audiences. SVT Sport’s successful work has been awarded with various national, regional, and international awards, including the world’s best sports channel in 2018 and Sweden’s most significant gender equality award in 2020.

Internally at SVT Sport, a change in culture was necessary to support the gender- and diversity- related work. There was some resistance in the beginning and a belief that it would be difficult to swing the pendulum, but it turned out to be much easier than expected. As Hamsch explained, “getting to overall gender parity was not that difficult, but we gradually turned up the complexity and started to look at sub-balances; if sports like soccer and hockey were excluded, how did that affect the balance? We learned through the process and sharpened our tools.”54

SVT’s commitment to continued monitoring of its performance also highlights the role of newsroom leadership in improving performance on gender equality indicators. Swedish public service broadcasters annually report on their general performance, which includes gender equality indicators, to the Swedish Broadcasting Commission, housed within the Swedish Press and Broadcasting Authority. However, this self- reporting is not supplemented by systematic independent monitoring of media content, to see if the broadcasters live up to the stipulations of the Broadcasting Permits. In other words, this is a soft policy and it is up to the broadcasters to invest in improving on these indicators.

Overall, SVT’s success is indicative of how media regulation, coupled with dedicated newsroom leadership, can spur transformative change. What started as one outlet’s effort to adhere to a new regulation not only resulted in a lucrative opportunity for that outlet to expand its audience, but highlighted an underserved market segment that other outlets were then incentivized to cater to.

The Macro Level: Media Regulation

The norm-building, policy reform, and implementation necessary to tackle the root causes of gender inequality in journalism can only be achieved through coordinated efforts among local, regional, and international actors. This extends beyond pushing for gender equality solely at the level of media content.

Media policy, at all levels—from outlets to national to international— should aim to tackle common workplace issues that marginalize women’s participation in the journalism labor market. In the absence of national policies creating mechanisms of redress for workplace sexual harassment, for example, media associations should join with women’s rights groups to advocate for such policies. Several international agreements have established goals for gender equality in a variety of sectors, including media.

At the international level, the most notable agreement is the 1995 Beijing Platform for Action (BPfA), which is considered normatively binding for UN member states. Section J of the BPfA calls on member states to promote “women’s full and equal participation in the media, including management, programming, education, training, and research” and “a balanced and non-stereotyped portrayal of women in the news media.”55 The BPfA offers a comprehensive set of proposals laying out a roadmap for change in the media sector. Yet, even when policies and agreements are in place, implementation remains a challenge. Perhaps the best indicator of the persistent lack of progress on the goals established by the BPfA is that nearly identical language is used to call for action 27 years later in the 2022 Joint Declaration on Freedom of Expression and Gender Justice.56

This lack of progress is reflected at the national level. Even for countries that have passed legislation to promote gender equality in the workplace, the measures are rarely applied to the media sector. State involvement in the sector through regulation could be perceived as an infringement on the sector’s right to operate freely and preserve its independence.57 This tension is apparent in countries where governments seek to weaponize national policy against freedom of expression and the press.

Self-regulation comes with its own set of difficulties. Argentina has had limited success at self-regulation from the press union Sindicato de Prensa de Buenos Aires (SiPreBA), which developed a protocol against workplace violence that some media houses have adopted. However, many media organizations sign on to international commitments, like the Unstereotype Alliance of UN Women, and national ones, such as the Agreement on Commitment to Gender Policies for Journalism and Advertising, but do not follow through on implementation. They also do not develop monitoring tools, so it is very difficult to measure progress.58

The limits of self-regulation are especially apparent regarding one of the most pressing issues affecting women journalists: online violence. Efforts in different parts of the world to counter online gender-based violence are curtailed by the absence of relevant or sufficient national legislation. When the legal definition of violence is limited to hate speech, for example, the law cannot be applied to address other expressions of violence, which for women are vast and continually evolving in tandem with technology.59

Sometimes the challenge is not the lack of laws, but gaps in capacity to apply the law or to adapt existing legislation created for the offline world to the digital sphere.

As a result, despite attempts by national governments to regulate online content through legislation, social media companies are left to regulate their own platforms. Self-regulation has not proven sufficient to address the issue, with online violence against women journalists running rampant on social media. According to a global study by UNESCO, nearly three-quarters of women journalists surveyed said they had experienced some form of online violence. Online threats can, in some cases, escalate to real world attacks. Twenty percent of the women surveyed were attacked or abused offline in connection with online violence they had previously experienced. The constant exposure to violence takes a toll on journalists’ mental health and can affect the way they do their jobs going forward. Thirty-eight percent of women respondents made themselves less visible and 30 percent began self- censoring on social media.60

The continued prevalence of these attacks is indicative of a failure of international and national regulatory mechanisms. The lack of support for women journalists who are victims of online violence points to a failure of newsroom policy and journalist support organizations. Only 25 percent of women surveyed for the UNESCO study reported incidents of online violence to their employers. Most received no response at all, others were told to “toughen up,” and some were asked what they had done to provoke the attacks.61

To combat this issue, digital platforms need to adhere to due diligence requirements, as set out in emerging statutory frameworks. The EU’s Digital Services Act, which sets new obligations for online platforms, is one potential avenue for holding these organizations to account for the spread of gender-based violence online.62 A group of regional regulatory networks, including the African Communication Regulation Authorities Network, the Mediterranean Network of Regulatory Authorities, and the Platform of Ibero-American Audiovisual Regulators, among others, also expressed their support for UNESCO guidelines for the regulation of social media.63 A number of national initiatives are also underway in partnership with international organizations like the United Nations Development Programme and Council of Europe, such as the projects to combat digital violence against women in Bosnia-Herzegovina.64

Despite these challenges, successful efforts in some countries illustrate the effectiveness of collaboration to build momentum for policy initiatives that address gender inequality in the media sector. In November 2023, 33 media houses in Rwanda signed up for the Rwanda Media Anti Sexual Harassment Policy, which will be monitored by a committee of media representatives. Local media proposed the initiative so they could refer to a set of guidelines when crafting anti-sexual harassment policies. A local expert created the resulting policy, and Fojo supported both the finalization of the policy and the creation of the committee.65

This initiative is part of a larger effort in Rwanda to build a gender- sensitive media policy framework. The latest draft of the country’s national media policy includes language specifying action items for the government that would improve working conditions for women journalists. These include helping media regulators develop an anti-sexual harassment policy, ensuring equal gender representation in the senior management of public media, and launching awareness campaigns to promote gender-sensitive reporting.66

The Rwanda case highlights the role international assistance actors can play in advancing gender equality goals by working with local actors to help implement the principles of supranational agreements and guidelines, such as the BPfA. The Protecting Independent Media for Effective Development (PRIMED) program, implemented in Bangladesh, Ethiopia, and Sierra Leone, is another case in point. As part of the program, media organizations in the three countries developed business models and organizational strategies to improve gender equality in the workplace and in media content and increase engagement with diverse audiences. To track progress, Free Press Unlimited, one of the implementers of PRIMED, developed a checklist based on a set of gender indicators developed for the program, which were, in turn, based in part on UNESCO’s gender-sensitive indicators for media.67

The program found that the more committed an outlet’s leadership is to improving gender equality, the more likely it is to make progress across the various indicators, even without funding support to cover the costs of necessary changes.68 For instance, a media outlet in Bangladesh found that other outlets in the country had adopted its strategy to improve women’s representation in content. This was due to concerted efforts by the outlet’s editor, who disseminated the outlet’s new editorial guidelines to other outlets through local press clubs and discussions with the leaders of other news organizations.69

International media development donors and implementers should prioritize strategic partnerships, in addition to funding, to advance gender equality in the journalism sector. In fact, the program found that forming paid partnerships with NGOs is one of the more lucrative ways for media to put out more gender-sensitive programming and engage women audiences.70 These partnerships not only improve media revenues and incentivize media leaders to commit to improving gender equality goals, but also provide a mechanism for monitoring and holding media accountable to gender-transformative change.

Regulatory mechanisms can positively impact gender equality in media. In the UK, under the 2017 Equality Act, all companies (including media organizations) over a certain size are required to publish their pay gap data. The regulation applies to private and voluntary sector organizations with 250 or more employees. For large public service media, this has resulted in public scrutiny and pressure for action. Following the publication of its data, the BBC had to redress its gender pay gap.

The UK regulator Ofcom provides guidance for broadcast licensing on equity, diversity, and inclusion: “Broadcasters have to make arrangements to promote equality of opportunity in employment between men and women, people of different racial groups, and for disabled people. They also have to put in place measures for training and retraining. These are conditions of their Ofcom licence.”71 Ofcom monitors compliance with license conditions and tracks progress over time in a transparent and measurable way.

Keeping countries accountable to making meaningful changes in service of those goals requires cross-national and cross-sectoral collaboration to advocate for and monitor their progress. Co-regulatory frameworks present one of the strongest opportunities to advance gender equality in the media. Co-regulation can fill the gaps left by self-regulation while providing independent accountability mechanisms that can prevent state overreach. However, for co-regulation to be possible, statutory and industry regulatory frameworks need to be in place.

In Canada, for example, private broadcasters established the Canadian Broadcast Standards Council (CBSC) to oversee broadcasting standards they had developed for themselves. It has been operating since 1991 with the approval of the state broadcast regulator, the Canadian Radio-Television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC). The CBSC is a self-regulatory body independent of the CRTC, which it provides with yearly reports on its activities. Complaints against broadcasters submitted to the CBSC by viewers or listeners are adjudicated by panels composed of representatives of the broadcasting industry as well as the public. The CRTC deals with complaints against broadcasters that do not participate in the CBSC and hears what are essentially requests for appeals from broadcasters unsatisfied with CBSC decisions. The CBSC’s codes and activities are meant to balance broadcasters’ need to preserve their freedom of expression, while remaining accountable to the public they are meant to serve.72 For instance, in response to public pressure, the broadcast industry developed voluntary codes on the portrayal of gender in media content, which are overseen by the CBSC. Although these codes resulted in some progress being made in improving the issue, the CRTC made compliance with the guidelines on gender stereotyping mandatory as a licensing condition for radio and television broadcasters.73

© UN Women/ Magfuzur Rahman Shana / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

This system is by no means perfect. When the CRTC first started delegating its standard-setting responsibility to the new self-regulatory body, a study found that, since CBSC is not required to choose its members through a democratic process, self-regulation could reduce public accountability. As a result, there is no process that formally requires it to justify its choice of council members, and there are few mechanisms for cooperation with other important actors in the media ecosystem, such as civil society.74 For co-regulation to meaningfully improve gender equality in media, the system needs to be truly inclusive and provide space for multistakeholder participation beyond the media industry and government.

For co-regulatory models to be effective, they need to emerge through dialogue among a variety of stakeholders, including the state, journalists, civil society, and experts in media policy and regulation. This type of collective action for policy development is especially crucial now. Although there is increased discussion in international forums around gender equality principles, actual progress has been slow to manifest. These discussions present an opportunity to develop concrete policy frameworks for advancing gender equality, but there are parallel discourses that can stall momentum. Not only is there growing opposition to gender equality and women’s rights by anti-gender movements in many countries, there is also a tendency to acknowledge issues like gendered income inequality without grappling with the underlying systemic problems. Multistakeholder dialogues toward co-regulation are a vehicle to potentially “build a new common sense” about the provisions for gender equality in the media ecosystem.75

Case Study 3

Somalia Gender Declaration

In Somalia, 47 media houses across the country have signed the groundbreaking Gender Declaration, which was developed by the Somali Women Journalists Organization (SWJO). Signatories pledge to implement 19 concrete and actionable points ranging from equal opportunity and pay to measures against sexual harassment.

Pursuing journalism is not easy for Somali women. They must conquer numerous obstacles and face discrimination in the workplace, such as gender pay gaps, fewer career opportunities, and sexual harassment in the newsroom and the field. After years of dissatisfaction with the situation, the SWJO was formed in 2017. SWJO started a nationwide process to create an action plan with concrete steps to improve the situation. Through a series of roundtable discussions, the organization brought together women journalists and media executives from across Somalia to discuss the challenges for women media professionals for the first time in the country’s history.

Based on these roundtable discussions and stakeholder meetings, including with representatives from the smallest news outlets and cities, an action plan was set. The Gender Declaration consists of 19 concrete and actionable points, which the SWJO invites media houses in Somalia to act upon to improve the situation for women working in media. To support the implementation of the Gender Declaration, the SWJO organizes yearly workshops and roundtable discussions across the country. For example, in 2022, it organized a series of roundtable discussions focusing on sexual harassment, maternity leave, equal pay, separate washrooms and prayer rooms, and professional development.

The Gender Declaration has so far profoundly impacted media in Somalia. Through the roundtables and follow-up meetings, an entirely new space for dialogue around gender equality has been created, including around the very sensitive topic of sexual harassment in the workplace. Media houses have reported seeing a changed attitude toward women journalists, better career opportunities for women journalists, and paid maternity leave. Almost a quarter of signatory media houses have amended their human resources policies to align with the Gender Declaration. Several of the media houses now have measures against sexual harassment in place. At least two media houses have installed CCTV (closed- circuit television) cameras to provide a safer working environment for women journalists, which, in one instance, captured sexual harassment on video and led to measures being taken against the culprit.

In addition to the Gender Declaration, other important initiatives have contributed to a gender transformative process. One such factor is the leadership training offered to women journalists by another civil society organization, the Media Women Network (MWN), which has thus far empowered more than 100 women. Thanks to the program, women have developed professionally, pursued careers, and acted as role models.

Abdirizak Sheikh Mohamoud, director of Star FM, one of the outlets that has signed the Gender Declaration, describes a radical shift: “We have changed our policy because of the agreement we signed with SWJO. We have promoted four of our very competent female journalists—not just because of their gender, but their professionalism and hard work,” he said. “There has been a huge change not only among women—their professionalism, capacity, and determination—but also the media have changed in terms of empowering women and giving them participatory roles in decision-making.”76

The Somalia case illustrates how a mix of strong local ownership and collaborative efforts by different actors in the media development community has the potential to catalyze change. In the late 2010s, several international media development organizations started or intensified their work in the country. This happened in parallel with the birth of two important local actors focusing on gender equality in the media: the SWJO and the MWN. The MWN was created as the local branch of the Women in News project, a World Association of News Publishers (WAN-IFRA) project that trains women journalists in leadership skills such as career planning, team management, communication, and negotiation. Both SWJO and MWN received support from a media development program implemented by International Media Support and the Fojo Media Institute (2019-2023), in turn with support from the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency.

Recommendations

All the issues and interventions discussed throughout this report are deeply interconnected. Policies and regulations will encounter pushback if women are shut out of leadership positions and market incentives are warped, incentivizing journalists to tailor their coverage to their funders (which could include governments or local political or business elites) rather than their audiences.

Women will have trouble attaining leadership positions if there are no policies ensuring equal opportunities in hiring and advancement, or if women entrepreneurs cannot get funding from investors. Market forces will not shift without regulation and sustained advocacy from sector leaders.

Tackling these interlocking issues requires a holistic approach that brings together cross-sectoral and transnational coalitions committed to designing and implementing strategies for industry-wide change. Given the cultural nuances and sensitivities of women’s experiences and needs, supporting grassroots movements of women media professionals and women’s rights groups more broadly is integral to developing effective interventions. The international assistance community is well-positioned to provide technical support and financial resources to multistakeholder national and regional coalitions aiming to improve gender equality in the media.

© Flickr / UN Women Europe and Central Asia / Volodymyr Shuvayev / CC BY-NC 2.0

One recent example of multisectoral collaboration is the Kigali Declaration on the Elimination of Gender Violence in and through Media in Africa.77 The declaration addresses the critical issue of gender-based violence (GBV), both regarding the kinds of violence women in media experience and how media represent GBV in their content. It was collaboratively created at the African Women in Media Conference in December 2023 as a working solution that might guide media organizations, media practitioners, academics, civil society organizations, and media partners and allies in their work toward creating a safe environment in and out of the media. To date, 93 individuals and organizations have signed the declaration.78 There will be a funding mechanism, connected to the declaration, that allows for financing of initiatives and projects that are aligned, and progress will be monitored on a yearly basis.79

This type of intervention exemplifies several best practices for gender- sensitive media regulation. It highlights the need to work at multiple levels of society, with policies and regulations that apply to a broad section of the population, consistent monitoring of progress on the implementation of those policies, and individuals and organizations steadily working to put those policies into practice.

At the macro level involving the state and society, four clusters of measures were evident based on the recommendations that emerged from the workshops. These pertain to regulation (legislation and policy), performance monitoring, advocacy, and awareness. At the meso level of industry, monitoring, awareness, self-regulation, capacity-strengthening, accountability, and financing were proposed. At the micro level, concerning individual outlets and media professionals, three measures emerged regarding policy, hiring, and media content.

Macro Level: State, Society, and across All Stakeholders

The Beijing Platform for Action Section J on “Women and the Media” remains the most comprehensive normative framework for actions that should be taken to build and promote gender equality in the media sector. It is important that countries, media development agencies, industry associations, media organizations, and civil society reference the specific measures, expand them, and devise innovative strategies to enhance implementation. Mainstreaming gender equality in the mandates, policies, and programs of government- and industry- level media governance bodies is crucial.

Advocates for gender equality in media recommend a whole- of-society approach to regulation through the establishment of sustained multistakeholder dialogues that engage government, media organizations, the private sector, civil society, and researchers to find consensus points that may translate into intervention measures. This role is one that state and industry regulators should lead, ensuring equal representation of different groups of women. Such platforms can break new ground and drive the articulation of gender-sensitive national co-regulatory frameworks.

Gender-based violence online is a new frontier in threats to gender equality in the media sector. Global tech companies have gained significant ground as the main distributors of news and information, often without taking ethical or editorial responsibility on numerous issues including gender equality and women’s rights online. It is urgent that transnational regulators as well as intergovernmental and regional self-regulatory bodies define international standards and regulatory mechanisms to address online GBV and protect the rights of women and vulnerable groups in the digital space. Legislation-enactment processes can draw inspiration from existing GBV laws based on an understanding that “what is illegal offline should also be illegal online.” Transnational regulators should press and encourage digital corporations to participate in standard-setting. The next step is for national regulators and self-regulators to ensure the norms and approaches are localized to the country context, with measures to enforce compliance by platform providers and users.

Governments have a key role to play in holding media accountable for integrating a gender-balanced perspective. Policy and legislation already exist in many countries, where regulators are tasked with monitoring the performance of publicly funded and independent media operating in their jurisdictions. Governments—in collaboration with industry associations, academia, and civil society—should establish monitoring processes that can generate the evidence needed for driving compliance at the national and transnational levels.

Civil society groups—particularly those focused on women’s rights and gender equality—are responsible for gender equality gains in most societies around the world. These groups shoulder the responsibility of advocacy to build awareness and encourage the rise of a culture supportive of gender equality. Governments, media development agencies, and the private sector should offer the support needed by these groups by providing financing and technical capacity to continue, scale up, and increase the impact and sustainability of their initiatives.

What the media development community can do: Macro Level

Integrate an intersectional perspective into all interventions, while being attuned to the needs of different groups of women.

Meso Level: Industry Bodies and Media Development Agencies

Global research reveals that only a few countries have adopted gender- sensitive media codes that go beyond a simple prescription to avoid discrimination based on sex or gender. A gender equality perspective must be integrated when codes are revised, or new ones drafted, and should at a minimum also include clauses on gender stereotyping and gender-balanced news sourcing. The details may be the purview of editorial guidelines in newsrooms; however, they often follow industry guidelines. Industry bodies need to take the first step in drafting more robust gender equality standards, and should monitor and disseminate performance and compliance results.

Industry-level voluntary associations should exert their power to foster women’s participation throughout the self-regulation process, from decision-making to design and implementation. Given the authority that industry associations have over their members, they are well-suited to mobilize media outlets around shared commitments. Such bodies should agree on transparent principles regarding gender equality in industry structure and operations, enshrine the principles in ethics and practice codes, and commit to implementation.

Aid agencies that fund media development should integrate gender equality indicators in frameworks to evaluate the performance of partnerships with news outlets, media development implementers, and media-based civil society. It is important that funders incentivize standard-setting when making funding decisions. Deliberations with women media owners and entrepreneurs as well as civil society groups that support media are crucial to designing these approaches for the sector.

What the media development community can do: Meso Level

Champion and support transparency measures, such as whistleblowing functions, audit systems, and fact-checking, with integrated gender and diversity dimensions.

Micro Level: Individual Media Outlets and Media Professionals (with Support from the Media Development Community)

News organizations should take steps toward real transformation, with industry and civil society providing oversight to drive accountability. Newsrooms should mainstream gender balance across all content rather than creating a special “women’s section” in media products.

News outlets must also prioritize hiring and retaining women journalists and editors, and creating content that appeals to women audiences. Inexpensive tools can be leveraged to understand the needs and interests of different segments of the population, such as third-party data sources like market analysis and web analytics for digital platforms.

To mainstream gender equality throughout the organization, individual media outlets should adopt and implement gender policy in human resources management in areas such as recruitment, promotion, leave, and remuneration. In addition, content-related policies need to be in place, such as gender-sensitive editorial guidelines, style books, and specific guidance on how to report on GBV. Capacity in gender-sensitive reporting in general and GBV reporting in particular needs to be built among staff.

What the media development community can do: Micro Level

Support initiatives that promote ethical, gender- balanced, and diverse news production, including feminist media initiatives.

The Way Forward for Media Development Support

Gender equality is a global goal and the media are key players in its achievement. In turn, gender equality holds the potential to improve trust in media, expand high-quality coverage of underrepresented issues and communities, and strengthen media viability, especially in this ongoing time of crisis. Media assistance organizations and donor agencies should embrace the whole-of-society approach, collaborating with local actors and across sectors to strengthen media organizations and advance a pluralistic, diverse, and democratic news media sphere rooted in gender equality principles.

Yet, more research is needed to evaluate the results and impacts of gender and media development interventions so far. Ideally, a broad scope should be applied to identify what measures and tools are most impactful to help build on the theory of change of how gender equality in media can contribute to the development agenda at large. As 2025 will mark the 30th anniversary of the Beijing Platform for Action, the media development community needs to take stock of the progress the sector has made toward achieving gender equality and acknowledge that the road ahead is long and much more needs to be done.

Annex

Carolyn Byerly, “Advancing Gender Equality in Media Ownership, Management and Leadership” (Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance, October 2022), https://www.cima.ned.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Byerly-Media-Ownership-Abstract-Final.pdf.

Claudia Padovani, “Advancing Gender Equality in and through the Media through (Rethinking) Regulatory Models and Interventions” (Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance, November 2022), https://www.cima.ned.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/CPadovani_CIMA-workshop-December-2022-Final.pdf.

Rosemary Okello Orlale and Malak Monir, “Advancing Gender Equality through Media Market Dynamics” (Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance, April 2023), https://www.cima.ned.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Media-Market-Dynamics-Abstract_Final.pdf.

Cover photo credits:

Main image: © Abdirahman Abukar Omar / Sucdi Abdifitab and Fatima at Somali National University

Left Top: Shutterstock.com

Left Middle: © Flickr / UN Photo/Antoine Tardy / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Left Bottom: © Flickr / UN Women-Ryan Brown / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Footnotes

- Luba Kassova, The Missing Perspectives of Women (AKAS, November 2020), https://www.iwmf.org/wp-content/ uploads/2020/11/2020.11.19-The-Missing-Perspectives-of- Women-in-News-FINAL-REPORT.pdf.

- Sarah Macharia, ed., Who Makes the News? The Global Media Monitoring Project 2020 (Toronto: WACC, 2021), https:// whomakesthenews.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/ GMMP2020.ENG_.FINAL_.pdf.

- For the purposes of this report, the term “gender” is used to refer to the distinction between women and men. While we understand that gender is a spectrum, the specific experiences of trans and nonbinary people, as well as those of the broader LGBTQIA+ community, were not the focus of this report. This important area needs more attention and funding.

- Monika Djerf-Pierre and Maria Edström, Comparing Gender and Media Across the Globe: A Cross-National Study of the Qualities, Causes, and Consequences (Gothenburg: Nordicom, 2020). https://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1502571/ FULLTEXT02.pdf.

- Sarah Macharia and Joan Barata, Global Study: Gender Equality and Media Regulation (Kalmar: Fojo, Linnaeus University, 2022), https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record. jsf?pid=diva2%3A1734313&dswid=-909.

- See, for example: Maurice Oniang’o, “Despite Abuse and Sexism, Women Journalists in Somalia Are Fighting Back to Do Their Job,” Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, May 2, 2023, https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/news/despite- abuse-and-sexism-women-journalists-somalia-are-fighting-back-do-their-job.

- Kirsten Eddy, Amy Ross Arguedas, Mitali Mukherjee, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen, “Women and Leadership in the News Media 2023: Evidence from 12 Markets” (Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, 2023), https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/women-and-leadership-news- media-2023-evidence-12-markets.

- According to journalists and media experts who participated in “Investigating Levers of Change for Gender Equality in Media,” Zoom, 2022–2023.

- “#WomenInFront: Women in the Unions: “Commitment is Key” Says Ratna Ariyanti of AJI, Indonesia,” International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), March 7, 2019, https://www.ifj.org/media-centre/news/detail/category/gender-equality/article/ womeninfront-women-in-the-unions-commitment-is-key-says- ratna-ariyanti-of-aji-indonesia.

- Eden Geremew, “Analysts Say Ethiopia’s Media Need to Empower Female Journalists,” Voice of America, April 4, 2023, https://www.voanews.com/a/analysts-say-ethiopia-s-media- need-to-empower-female-journalists-/7036307.html.

- Participant in CIMA-Fojo workshop, “Investigating Levers of Change for Gender Equality in Media.” Workshop Part 1: Gender Equality in Media Ownership, Management and Leadership, Zoom, November 14, 2022.

- Prue Clarke in an interview with Malak Monir, March 2, 2023, as cited in Rosemary Okello Orlale and Malak Monir, “Advancing Gender Equality through Media Market Dynamics” (Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance, April 2023), https://www.cima.ned.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Media-Market-Dynamics-Abstract_Final.pdf.

- Results from the 6th Global Media Monitoring Project (GMMP) show stellar performance of South African news media, not only in Africa but globally. South Africa was ranked fourth out of 100+ nations on the Gender Equality in News Media Index score calculated from the 2020 GMMP.

- Carolyn M. Byerly and Sharifa Simon-Roberts, “Women, Journalism, and Labor Unions,” in Journalism, Gender and Power, ed. Cynthia Carter, Linda Steiner, and Stuart Allan (London: Routledge, 2019), 79-93.

- “Women Journalists Partners in Trade Union Leadership,” IFJ, 2010, https://www.ifj.org/fileadmin/images/Gender/Gender_documents/Women_Journalists_partners_in_trade_union_leadership_-_Gender_facts_sheets_-_Middle_East_and_Arab_World.pdf.

- “IFJ Women Lead,” IFJ, 2018, https://samsn.ifj.org/iwd2018/.

- “Sierra Leone: Journalists’ Union Launches New Gender Policy,” IFJ, September 14, 2023, https://www.ifj.org/media- centre/news/detail/category/gender-equality/article/sierra– leone-journalists-union-launches-new-gender-policy.

- Byerly and Simon-Roberts, “Women, Journalism, and Labor Unions.”

- Carolyn Byerly, “Advancing Gender Equality in Media Ownership, Management and Leadership” (Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance, October 2022), https://www.cima.ned.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Byerly-Media-Ownership-Abstract-Final.pdf.

- “Sponsors,” Gender Links, n.d., https://genderlinks.org.za/ about-us/partners/sponsors/, accessed February 27, 2024.

- Digital native news outlets are news organizations that were founded online, rather than through a more traditional medium like print or broadcast.

- Warner et al., “Digital Media Teams,” Inflection Point International: A Study of the Impact, Innovation, Threats, and Sustainability of Digital Media Entrepreneurs in Latin America, Southeast Asia, and Africa, (SembraMedia, 2021), https://data2021.sembramedia.org/reportes/chapter-4-digital- media-teams.

- Project Oasis: A Research Project on the Trends, Impact and Sustainability of Independent Digital Native Media in More than 40 Countries in Europe (Project Oasis Europe, 2023), https:// projectoasiseurope.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/ Project-Oasis-PDF-April-17-2023.pdf.

- Jie Wu et al., “The Performance Impact of Gender Diversity in the Top Management Team and Board of Directors: A Multiteam Systems Approach,” Human Resource Management 61, no. 2 (2022): 157-80, https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.22086.

- Moez Bennouri et al., “Female Board Directorship and Firm Performance: What Really Matters?” Journal of Banking & Finance 88, no. 88 (2018): 267-91, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jbankfin.2017.12.010.