The election June 7 in Turkey dealt a significant blow to President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s plans to transform Turkey’s government into a presidential system—which would have significantly strengthened his political dominance over Turkish politics. Turkish voters may have also provided an opening for independent media to regain its footing in an environment that was crumbling under the weight of Erdogan’s political ambitions.

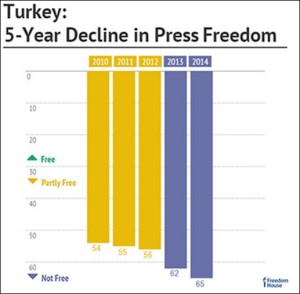

Under Erdogan’s stewardship as prime minister, and for the past 10 months as president, Turkey’s independent media has been under siege. Independent news outlets, and especially those associated with U.S.-based Fethullah Gülen, have been raided, journalists have been arrested at an alarming rate over dubious charges, and the much-criticized and long-standing anti-terrorism law continues to be wielded by authorities as a weapon against dissent.

According to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), Turkey had 40 journalists in prison as of December 1, 2013, making it the world’s leading jailer of journalists for the second consecutive year.

Given the dire state of media freedom in the country, the election of June 7 was welcome news, to say the least. As Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) lost its majority in the Turkish parliament for the first time in 13 years, the election’s biggest winners, the Republican People’s Party (CHP) and the pro-Kurdish People’s Democratic Party (HDP), could help re-establish Turkey as a beacon of media freedom in an otherwise repressive region. In particular, these parties look likely to seek reversal of some of Erdogan’s most draconian media laws. For instance, the CHP has already identified the 2014 Internet Law, which amended previous legislation to allow Turkey’s telecommunications authority (TIB) to block websites without first obtaining a court order, as priority legislative targets in their campaign to reverse the AKP’s assault on the Turkish media sector.

Perhaps the most interesting development from the June 7 election, however, is the surprise success of the pro-Kurdish HDP, which has entered parliament for the first time with 79 seats. Traditionally focused narrowly on Kurdish issues, the HDP was often undermined nationally by its connections to the Kurdish separatist group the PKK. However, the party successfully broadened its appeal by reaching out to independent candidates across the country and targeting disaffected AKP supporters by espousing a left-wing agenda, with particular focus on the rights of women, minorities, and those in the LGBT community

The HDP’s progressive, secular political agenda should play well for independent media in Turkey. Elsewhere in the world, the emergence of left-wing parties and coalitions has proved to be watershed moments for improvements in the political and legal environment for media. A 2014 post on CIMA’s blog about the success of media reform in Uruguay outlined how the emergence of such a coalition helped eventually pass landmark media reform legislation and helped transform Uruguay into a regional leader in media freedom. In that instance, the left-wing coalition had no particular agenda but surged to electoral success on a pro-human rights platform, not unlike the HDP’s strategy in the Turkish election.

If the HDP is serious about a progressive human rights agenda, the media should be central to its efforts to effect change in the country and become a force for progressive politics in a country that badly needs a reboot.

Comments (0)

Comments are closed for this post.