The Philippines is Asia’s first democracy. A country where freedom of expression and of the press are constitutional rights.

Although the Philippines is not a war-torn country, with 77 journalists killed in the last 20 years, it is the world’s third-deadliest country for journalists, behind Iraq and Syria, and worse than even Russia. Such a baffling paradox for a democratic country.

Worst attack against journalists

This month marked the start of the filing of Certificate of Candidacy for next year’s national elections in the Philippines. A time reminiscent of a horrendous incident six years ago when 32 defenseless journalists were massacred.

In November 2009, Esmael Mangudadatu, gubernatorial candidate from the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, sent a convoy that included his wife, lawyers, and some relatives to file his certificate of candidacy in Sultan Kudarat. Journalists joined them to cover the story.

The convoy was stopped at a hilltop in the town of Ampatuan in Maguindanao by more than a hundred armed men. All 57 people, including the 32 journalists, in the convoy were brutally killed. Some were beheaded, and the women were reportedly raped. A state-owned backhoe was used to bury bullet-riddled corpses, in an attempt to clean up the crime scene.

The rival political clan of Ampatuans was believed to have plotted the ambush. The clan’s patriarch Andal Ampatuan Sr. was the incumbent governor. His son, Andal Jr, was running against Mangudadatu at the time. Both were declared prime suspects.

The carnage in Maguindanao was the most horrific election-related violence in the history of the Philippines, and also the world’s worst-recorded attack against journalists.

Flawed Democracy

The Maguindanao massacre changed the landscape of freedom of the press in the Philippines. It also exposed the many flaws in Philippine democracy, which become even more evident during elections.

In the Philippines, especially in the rural regions, local governments are disguised feudal systems. Political families have been ruling towns and provinces for decades. Government seats are their family’s heirloom. The government’s money is their clan’s wealth.

These political families splurge on luxury while the greater population suffers poverty.

Local journalists who investigate and expose corruption in the government suffer a wide range of harassment. Worse yet, many of the hard-hitting journalists were killed.

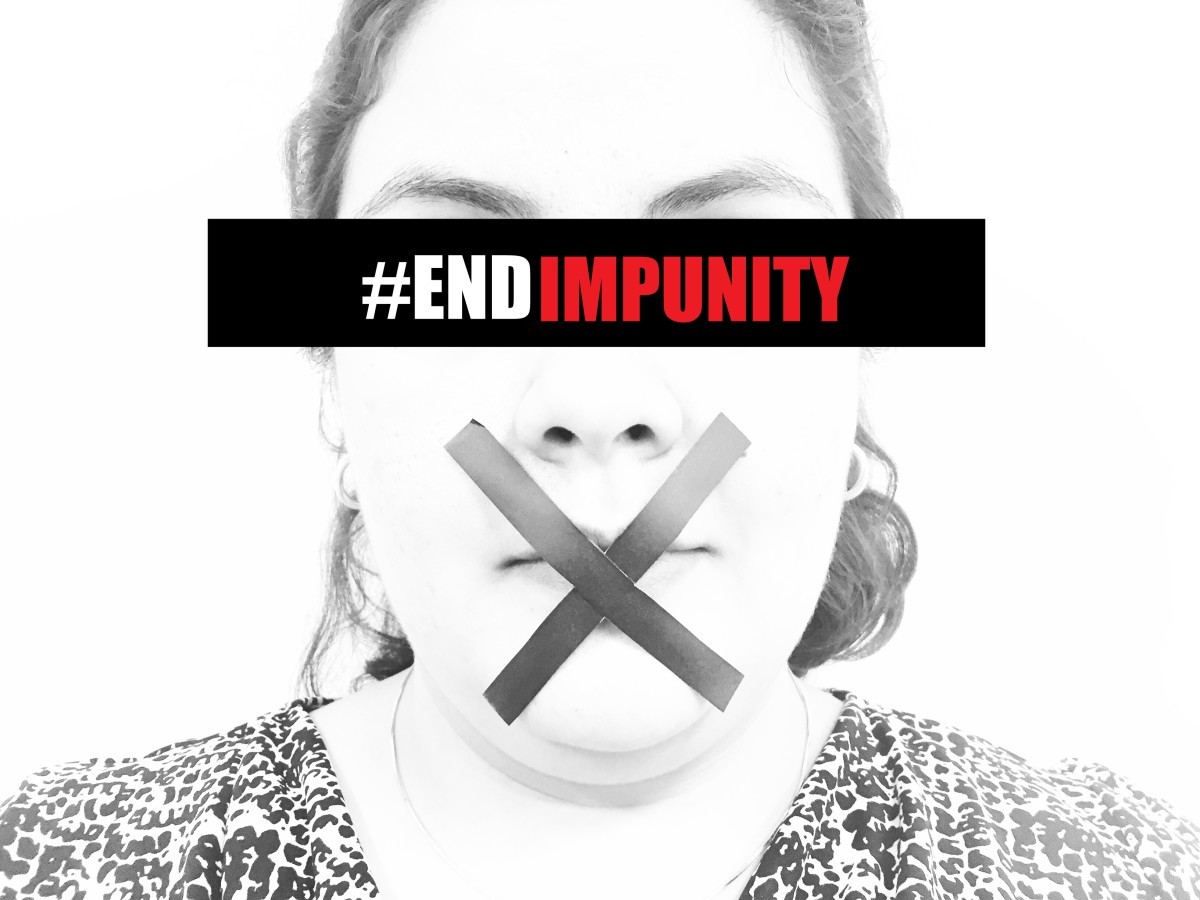

Culture of impunity

According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, 68 of the 77 murder cases of Filipino journalists remain unresolved. Those reporting on politics and corruption accounted forthe highest number of death.

For years, perpetrators of crimes against journalists enjoy shameful impunity in the Philippines.

In the six years that have passed since the Maguindanao massacre, none of the more than 100 suspects has been convicted. A number of witnesses and loved ones of the victims were bribed into silence. Several witnesses were killed.

One of the witnesses, Dennis Sakal, a former driver of Andal Ampatuan Jr, was killed in an attack on his way to meet a prosecutor in November last year.

The prosecution is inching its way through the Philippine judicial system. To date, the case is still in the bail petitions phase. Families of the victims and civil society organizations have continually criticized the government for the slow process of justice.

Several families of the murdered journalists reported threats and intimidation. Many were also suffering financially, as most of those killed were breadwinners.

In March, Sajid Islam Ampatuan, one of the suspects, also son of Andal Sr., was ordered temporarily release after posting a whopping PHP11.6-million ($250,000) bail. Now, he is back in politics, running for mayor of town Sharif Aguak in Maguindanao. Sajid Islam is running against his cousin and sister-in-law.

Andal Ampatuan Sr. died of a heart attack in July, asserting his innocence until he slipped into a coma, according to his lawyer.

Despite the massive outrage, Ampatuans still enjoy high positions of power.

Getting away with murder

Philippine media is among the most progressive in the world. Backed up by a nation known as a social media powerhouse, the media in the Philippines is also among the most innovative.

Despite all this, it is baffling that Filipino journalists remain among the most vulnerable to threats and violence.

A close analysis of these murders reveals that most of those killed are working in rural regions. This also exposes the gap between the national media and the community-based media in the Philippines. A system where the national media, especially the celebrity presenters, are much glamorized, popular, and highly paid, while those working in rural communities are paid less but subjected to more threats and violence, and have marginalized access to training and other opportunities.

The combination of a very slow justice system, poor forensic technology, and a predominantly feudal system of local governments equates to an alarming culture of impunity–where for perpetrators of crimes against journalists, getting away with murder is child’s play.

Makoi Popioco is a journalist and the current Hurford Youth Fellow with the World Movement for Democracy at the National Endowment for Democracy

Comments (0)

Comments are closed for this post.