By Gideon Sarpong

The rise of social media platforms provides many opportunities to the more than half a billion internet users in Africa, including increased access to information and extended social networks. However, these platforms pose new challenges to protecting the safety of journalists. In many countries, social media have become toxic online spaces where threats to journalists proliferate.

For many journalists in West Africa, social media platforms are spaces for brutal, prolific online harassment and abuse, including targeted attacks that erode the foundations of journalism by chipping away at journalists’ resolve to provide independent, critical reporting of crucial issues. According to a 2020 survey carried out by UNESCO in 15 countries, 73 percent of women report experiencing online violence. Facebook and Twitter were ranked the least safe of the top five platforms used by female journalists.

Award-winning Nigerian journalist Ruona Meyer was targeted in a campaign of extreme online harassment, which lasted almost a year following the publication of her BBC investigation into Nigeria’s cough syrup cartels. Due to her marriage to a German citizen and her association with the BBC, she was accused of being a ‘foreign agent’ by anonymous trolls.

Several leading journalists in Ghana, including Evans Mensah, Israel Laryea, and Gifty Andoh-Appiah, have also received death threats online following the December 2020 elections. A report by the Media Foundation for West Africa captures one of the threats sent directly to journalists’ personal Facebook inboxes: “We are coming for you. You[r] evil deeds that you colluded with your paymasters to perpetrate during the 2020 elections are exposed and well in the public.”

These threats often lead to physical harm. In 2017, the Committee to Protect Journalists found that in at least 40 percent of cases, journalists who were murdered had received threats, including online threats, before they were killed.

Although social media platforms are increasingly exposing journalists to online harassment, it is hard for many journalists to abandon these platforms altogether because they have become an essential part of their work. Many journalists today rely on social media for posting and promoting their content, following their favorite websites, and interacting with their readers, listeners, or viewers.

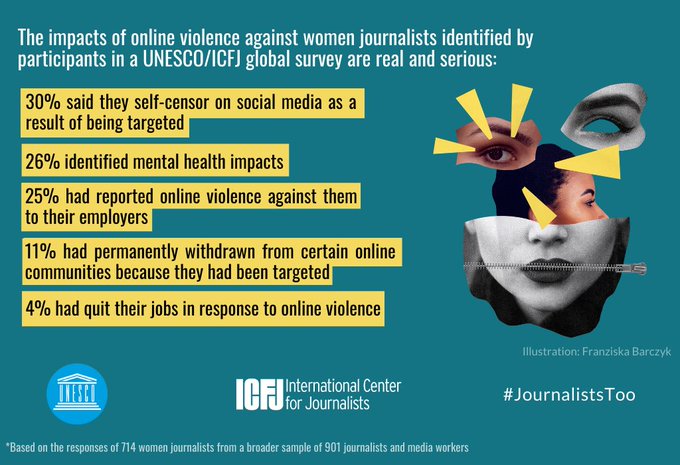

Despite these benefits, women in particular face risks online. Several studies have found that women journalists were disproportionately subject to online harassment. The repercussions of these constant attacks can be serious. The UNESCO survey found that many women journalists have had to deal with mental health issues as a result of online violence, and many others have resorted to self-censorship, complete withdrawal from all social media interaction, and avoidance of audience engagement.

Online violence poses a significant risk to the free flow of information, press freedom, and the democratic exchange of ideas. This means that newsrooms and social media companies must take urgent action to mitigate the problem. Social media companies are failing to stem online violence against journalists globally, leaving the burden on newsrooms and journalists to navigate this minefield.

A 2019 study by the International Press Institute on newsroom best practices, notes that newsrooms with online safety units—one or two designated staff members responsible for tracking cases of harassment and coordinating a response—have proven effective at pre-empting online attacks and addressing those concerns. It concludes that, “without a healthy culture of safety in the newsroom, cases of online harassment—including those that have a profound impact on journalists’ professional and personal lives—will go unreported.”

Research conducted by iWatch Africa on the safety of journalists online provides useful data and recommendations to help newsroom managers in West Africa tackle a problem that is only likely to grow.

The following key considerations are extracted from the guidelines.

- Build Digital Rights Literacy in the Newsroom

Understanding digital rights is an important step in addressing the psychological, physical, and digital safety effects of online abuse. Newsroom managers should make sure their journalists understand how human rights manifest online and how to recognize when those rights are violated. Digital rights literacy is also important in helping journalists participate in discussions about policy development. Ultimately, journalists and media organizations will need to become more involved in digital governance discussions at national, regional, and even global levels in order to truly affect change in this area.

- Create Clear Lines for Reporting Abuse

Newsroom managers must make clear that the media organization itself takes online violence and abuse very seriously. This sends two important messages. First, it helps debunk the widespread feeling among journalists that being targeted with abuse on social media is the new normal. And second, it gives journalists a sense of security that media organizations will support them.

- Conduct Risk Analyses

Newsroom managers must take steps to understand the types of risks that their staff and contributors are facing online. A thorough risk assessment is important to determine which type of support is the most appropriate in the event of an online attack. For example, a credible online threat that is likely to lead to physical harm against a journalist may require newsrooms to report the threat to the police and provide security protection for the journalist involved.

- Implement Support Mechanisms

Support mechanisms need to be put into place to ensure that journalists are able to work without fear of harm or abuse. For example, a journalist could be provided legal support if bringing legal action against an online aggressor would deter future behavior. Other support mechanisms may include psychological support, digital security support, and peer support.

- Appoint an Online Safety Coordinator

Newsroom managers should appoint an online safety coordinator to whom journalists can report incidents of online harassment. This person would also assess each case of online harassment in coordination with targeted journalists and editors and suggest the appropriate support mechanisms.

Online harassment has become a new mechanism to censor news content. By inundating journalists with a seemingly endless barrage of insults and threats, harassers hope to dissuade specific journalists and even news organizations from covering certain topics. The constant attacks can impact journalists’ quality of life and have, in some cases, affected news coverage. According to a 2017 Council of Europe study, 31 percent of journalists toned down coverage of certain subjects after being harassed, 15 percent dropped the story altogether, and 23 percent did not cover certain stories. The impact on press freedom is all the more dangerous because of the widespread nature of this new threat—it is easier than ever for social media users to deploy armies of faceless bots against their targets. A credible plan to protect journalists and effectively address online harassment is therefore critical to sustaining press freedom and, ultimately, enabling a thriving democracy.

This guide is not intended to be a one-size-fits-all set of protocols. Rather it should be adapted and modified to fit the needs of individual newsrooms. In the long run, these guidelines will require constant reassessment and updating to accommodate rapid changes in technology, social media tools, and the political landscape behind online attacks.

The complete guide can be downloaded here: https://openinternet.global/resources/guidelines-newsrooms-west-africa

Gideon Sarpong is a co-founder of iWatch Africa and a Policy Leader Fellow at the European University Institute, School of Trans-national Governance in Florence, Italy. These guidelines were put together by Gideon Sarpong during his fellowship as a 2020/21 Open Internet for Democracy Leader. Gideon is also currently a visiting scholar at the University of Oxford, United Kingdom.

Comments (0)