This post originally appeared on softcensorship.org.

WAN-IFRA

Don Podesta, manager and editor at the Center for International Media Assistance (CIMA) based within the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) in Washington D.C., published ‘Soft Censorship: How governments around the globe use money to manipulate the media’ in 2009. Today, he believes that governments are increasingly using soft censorship, and evermore sophisticated economic pressures and forms of intimidation, to silence critical reporting and reward positive coverage.

As a partner in WAN-IFRA’s on-going Soft Censorship research, Don spoke to Mariona Sanz about some of his concerns regarding the development of one of the least acknowledged, but arguably most pernicious forms of modern censorship.

WAN-IFRA: You started researching soft censorship in 2008. What did you uncover?

Don Podesta: I identified three main forms of indirect government censorship. The first was manipulating government budgets to reward media that are compliant with local or national governments and punish critical media. The second form, if not directly using government money, was pressuring businesses to advertise in some media and not in others. In China, Hong Kong or Taiwan, for example, I found that the government put pressure on big state companies, airlines and banks to withdraw their advertising from independent publications, so it was not the government itself but its pressure on commercial entities. The third version, which blends into corruption, is paying journalists directly to write a story. Why buy an advertisement if you can buy a story? This form is particularly prevalent in Ukraine where they have this phenomenon called “jeansa” [term for the blue jeans that journalists typically wear]. This practice can become two-way blackmail, as the journalist can also collect money for not writing something.

How has soft censorship evolved since then? Are there new practices you are identifying?

In my view, the definition of soft censorship has broadened to include new forms of economic pressures. An example would be Venezuela right now, where, because of the lack of foreign exchange, there are restrictions on the importation of newsprint. Independent newspapers do not have enough newsprint to produce their newspapers, and some are even borrowing paper from neighbouring countries like Colombia and Brazil.

There is also another prevalent form, perhaps closer to direct censorship, related to the licensing of broadcasters. If the government does not renew your broadcasting license, you are out of business.

Finally, we are seeing forms of online indirect censorship promoted by countries that traditionally had hard censorship. So-called “trolls” or government-supported people make nasty comments online to intimidate journalists. Russian trolls, for example, are commenting about the conflict with Ukraine and make a lot of noise on the Internet to silence journalists.

Can such forms of intimidation, like trolling for example, really be considered soft censorship?

They are pretty harsh, but indirect. For me hard or direct censorship is the old notion of “if you publish this we are going to close down your organisation,” or pre-censoring. By intimidating reporters by saying nasty things no one is stopping the journalist, who can still write and the article will be posted on the newspaper’s webpage, but s/he might think twice before writing again on the topic if people are going to accuse her of being a prostitute or an idiot. Intimidation is a form of censorship.

In fact, how can we distinguish clearly between soft and hard censorship?

There’s a spectrum from the hardest to the softest censorship practices, and in between it is a matter of judgment whether we call them hard or soft. If they are related to economic or regulatory pressures, I call them indirect or soft. Physical attacks, direct censorship or withdrawing licenses would be rather hard forms. In other words, if the pressure prevents the article or the media from going out, it is hard censorship. Something that inconveniences the media or causes economic damage is indirect censorship. In fact, self-censorship is one of the major consequences of soft censorship.

And governments are increasingly using these indirect forms?

Yes, governments are much more sophisticated right now. They do not send soldiers to a radio station to take possession of it. Now they use money or place the regulatory burden on organisations with regulations, tax audits and requirements for more documentation. As most information can be found on the Internet, and they cannot close it down, they have discovered other ways to influence content. It’s disheartening that there are so many forms; we are finding new soft censorship practices all the time.

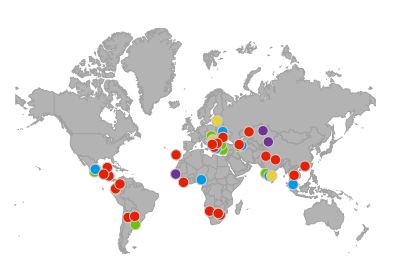

Have you identified regional trends?

Every country is different. Some of the threats that are common, and across regions is what we call “brown envelope” journalism, taking money to do stories. You see a lot of this in Africa or Asia, where it is called “red envelope” journalism.

In South America, from a study of seven countries conducted in the region, it came out that the pressures from city, regional and even national governments were very similar across borders. But inside countries you find local phenomena, as for example in Colombia, where radio reporters in provincial cities like Cartagena pay station owners for air time and cover the expense by selling advertising to the same government officials they cover. Essentially, this means interviewing officials in the morning for a news report and contacting them in the afternoon to solicit advertising. I have not seen this phenomenon in Asia or Europe. Some characteristics are unique to certain places.

What are the effects of soft censorship for journalism?

Soft censorship is very deleterious for journalism. It makes it difficult for newspapers to speak truth to power, to do investigative reporting. It takes away some of the watchdog function of a news organisation because outlets are not going to bite the hand that feeds them. This means the public does not get the information that they should be getting.

From our monitoring, we see that soft censorship happens also in countries with apparently no press freedom related problems.

Yes, in fact, when I wrote my paper I turned it into an op-ed for the Washington Post, where I mentioned that the Illinois governor at the time reportedly threatened to withhold state assistance from a deal involving the sale of Wrigley Field, owned by the Tribune Co., if the paper did not fire members of the editorial board whom he viewed as highly critical of him. Even in the United States a governor of a large state can use his power over state funds to punish a big institution. Soft censorship happens everywhere.

Why should people care about soft censorship?

First of all, because it is taxpayers’ money and it must be distributed equally. This process has to be transparent and there should be an oversight body, which is not politically appointed, to ensure that the standards are being upheld. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression and several think tanks have produced recommendations on that score. If the government is going to advertise, it should also be responsible for measuring the audience to ensure the citizens are getting the proper value for the tax money that is being spent on it. Audience measurement is important, as well as audience appropriateness. For example, what sense does it make to have advertising for tourism in a local paper? If people come to Patagonia to see the wonders of that area, and you put the advertising in the local paper of that same province, it makes no sense.

Are international legal instruments that attempt to regulate government advertising useful?

They would be useful models if they were followed, but much like for other freedom of expression clauses, all countries sign on but then their presidents and ruling people define and redefine them in the way they want. Venezuela for example is a signatory of the conventions concerning freedom of expression, but the government is not behaving in that way. Which are the enforcement mechanisms for international conventions? The goals are clear, but the execution is different from country to country.

Why do you think that soft censorship does not generate greater international outcry and interest?

The obvious reason is that there is so much spectacular violence against journalists right now, including beheadings, assassinations, imprisonments, that indirect censorship is not very visual and not as exciting compared to the drama of a journalist being put in prison or killed.

The second reason is that soft censorship happens in the world of commercial and monetary transactions, and that publishers are the ones who care the most about this. I was on the board of directors of the Inter American Press Association for about a year and a half and went to a couple of their conventions. Soft censorship was on the top of their list.

Comments (0)

Comments are closed for this post.