By Justin Kosslyn

Official donors from around the world spend upwards of $650 million a year on media development. They are spending their money with the expectation that it will meet a technical challenge: training writers to craft good stories, providing equipment, coaching managers on business skills, and so on. But at the Eighth Assembly of the World Movement for Democracy, in Seoul, South Korea, last week, following the second highest year for journalist arrests on record and just before the release of prominent Egyptian journalist Bahgat, it became clear that such techniques, while necessary, are not sufficient.

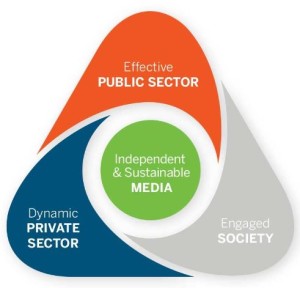

Media does not exist in a vacuum. Successful media development requires building the will and structures to sustain independent media—including legal reforms, civil society engagement, and business community support.The development community should consider broadening its focus.

The organizations that are working so hard to create the supply of good media might help unleash the demand for it. An ecosystem will grow, as long as it’s allowed to. It is past time, in other words, to develop media in the context of real societies.

Over the past several years in Ecuador, for example, the public has expressed discontent about the uneven quality of the media. According to the Eighth Assembly (as all cases offered for consideration in this article are), the government has channeled that frustration into new censorship legislation and enforcement actions against independent media—much of it aimed at discourse control, not quality control. For example, the government has imposed large fines for the publication of satire. The media has lost control of its own narrative.

Uruguay is a positive counterexample. Its far-sighted government took the initiative to pursue pro-media legislation guaranteeing freedom of expression, and community and business groups created consortia to advance the cause independently. A very broad and deep coalition, with diverse perspectives and constituencies, came together in a classic political movement to work towards one of the most important reforms of a major media market in Latin America. But it perhaps would not have been possible without the political DNA contributed to the movement by the government itself.

In both cases, however, the outcome was not determined by how much money was thrown at media outlets, but by the context in which journalists were publishing their content.

This is true in Southeast Asia as well as in Latin America, although the current state of media affairs varies greatly from one to the other. The tradition of organizing politically is only beginning in Southeast Asia. Before 1998, there were no independent media organizations in the region that would fight for media freedom, just international groups like the Committee to Protect Journalists. In the last couple decades, though, groups like the Southeast Asia Press Alliance have stepped forward, spreading to Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines to help advance media development beyond technical support.

Nepal illustrates the limitations of a traditional media development approach. The country has enjoyed legal freedom of media since 1990. But advertising revenue has concentrated on print media (which is mostly controlled by a single publisher), rather than the country’s more than 500 radio stations, most of which are run independently. International development money ends up funding those stations, but is earmarked for traditional content production. So the political media landscape has remained monopolar, and public advocacy still has room to develop. But here, too, the point is not that there is a need for funding, but also that there is a need for funding in a society that will let politically critical media outlets receive it.

One approach can be to leverage South-South learning. Successful reformers like Uruguay can help other countries where reforms are less advanced, and to put pressure on governments that are reluctant to take reforms forward.

Another approach—one suggested by the Center for International Media Assistance—is to focus on laws, regulations and other enabling factors that ensure that media is allowed—and encouraged—to play a constructive role in society. This means getting comfortable with funding journalism that informs people about the issues critical to their lives and holds governments and other powerful forces to account for their actions.

Finally, there is power in uniting the spectrum of stakeholders in each country to create coalitions across constituencies. Convening media and civil society to discuss these dynamics is a good first step, as the World Bank has shown.

Media exists in a context. Countries providing that context can learn from one another. Civil society must be developed to encourage and protect and consume a free and independent media. None of this is necessarily novel. But the media development community is not always doing this, or not doing enough of it. Civil societies need to be developed along with media. The one cannot exist without the other. And though it is not new, it needs to be considered in how we help foster news.

Justin Kosslyn is an Adjunct Fellow at New America’s Open Technology Institute.

This piece was also published in New America’s digital magazine, The New America Weekly. Sign up to get it delivered to your inbox each Thursday here, and follow @New America on Twitter.

Comments (0)

Comments are closed for this post.