Digital news and social media hold increasing sway over public opinion, but as the world’s largest democracy goes to the polls, it may be time to ask: Just how important is digital media in India?

Between April 11 and May 19, more than 900 million Indians will be eligible to vote in the nation’s parliamentary elections—an exercise of democracy so large that the electorate is divided into seven phases. As a flood of information and disinformation sweeps the country of over 1.3 billion people, many are worried about how online platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp may be used to manipulate public opinion and undermine the democratic process.

But while the digital news market is clearly booming, it is still the traditional media that reach the vast majority of Indians.

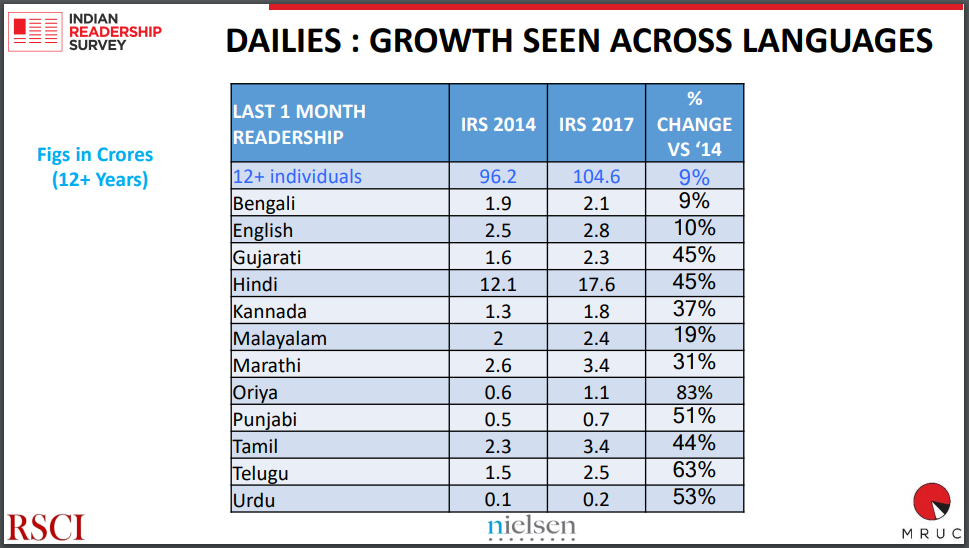

One report found a 60 percent increase in newspaper circulation from 2006 to 2016; another tracked an increase of 110 million readers of daily newspapers from 2014 to 2017. International attention is largely focused on the digital audience, and real-time numbers for anything else are hard to come by. But experts agree: newspapers and traditional media remain the leading source of information in India, and with them comes a substantial portion of the voting population often left out of the conversation.

The Online Electorate

Building off research from their annual Digital News Report, in March 2019 the Reuters Institute released a deep-dive report on the Indian media space. With elections now underway, how and where audiences access news in India is of critical importance. Yet, as the report emphasizes, the survey was conducted entirely online and in English. As a result it is “skewed towards male, affluent, and educated respondents”—a small, though important, segment of the massive and diverse population.

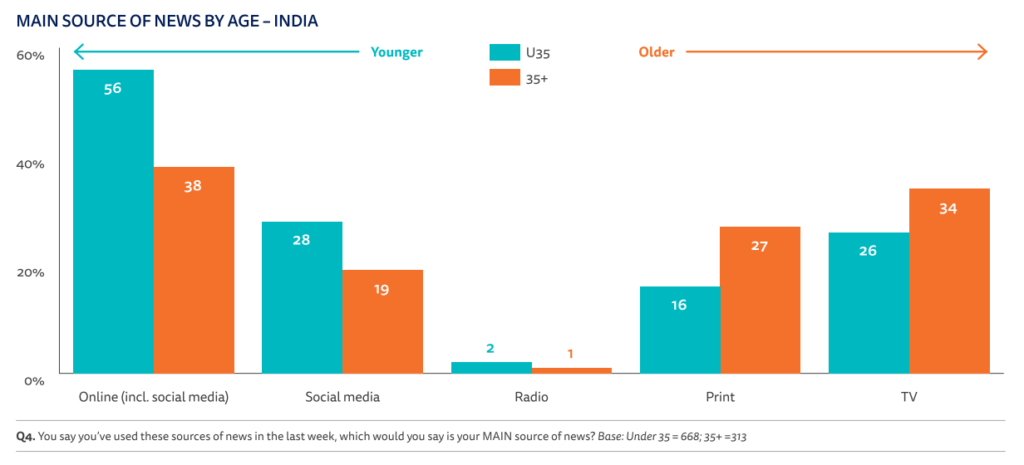

According to the Reuters Institute survey, those audiences are hugely mobile-first. Fully 68 percent of these respondents identify smartphones as their main device for online news, far surpassing similar cohorts in other developing markets like Brazil and Turkey. Online sources are now outpacing legacy media among respondents under 35, and these trends are expected to continue as literacy and internet access increase across the country.

As the report also highlights, internet access in India has grown at rapid pace, surpassing an estimated 500 million users by June 2018; 340 million of them make it Facebook’s largest country portfolio. Social network sharing, especially over messenger platforms like WhatsApp and Facebook, undoubtedly warrants the attention it’s been given—but those 500 million internet users represent just 30 percent of the country. And in the realm of likely voters, Reuters Institute respondents, while insightful, are even less representative.

…Everyone Else

Even as the report takes a deep dive into online news audiences, there is evidence throughout that “digital and print still supplement rather than supplant each other for many users in India.” Several leading English-language Indian newspapers, for instance, show a wider offline reach than online, in stark contrast to most other markets covered by the Digital News Report. Similarly, The Atlantic’s recent look at misinformation shared over WhatsApp briefly pauses to concede, “traditional media continue to be the dominant source of information for Indians.” According to the 2016 study they cite, “among those aged 15 to 34, 57 percent watch TV news a few days a week, 53 percent read newspapers at the same frequency, and about 18 percent consume their news on the internet.”

The 2017 Indian Readership Survey offers a more comprehensive look at the still-booming traditional media market. In 2017, the survey reported 407 million readers of daily newspapers across the country, having grown by 110 million in just three years. Over 60 percent of that increase is from rural audiences, with regional language consumption growing in leaps and bounds. As literacy rates expand, the market for news in regional languages grows with it. The simultaneous increase of internet access promises more change to come, but in the meantime, one article declared, “the future of India’s newspapers lies in the hinterlands.”

Despite the size of India’s traditional media, the high level of concern regarding the impact of online platforms on the elections is undoubtedly warranted. The dangers of mis- and disinformation have been highlighted in elections across the globe, and in India and in neighboring countries even in times of relative stability. And disinformation shared on social media is often picked up by the other players in the media space. If anything, however, these cases stress the need to better understand and adapt to the local context in combatting disinformation and supporting independent, trustworthy news outlets. That includes traditional and regional media, both frequently difficult to track.

Rural areas lead not just in a growing newspaper industry, but also in voter turnout and representation. In fact, urban turnout is consistently around 10 percent lower than the national average and only 18 percent of the electorate itself is urban, making the rural, often lower class voter an immensely important one. Indeed, roughly 70 percent of the population is neither urban nor online, and they are likely to exercise their right to vote over the next several weeks. The growth of traditional media, especially in rural areas, shows an audience hungry for news. Those concerned about the quality of public dialogue would be wise to factor in the often overlooked and incredibly important role of traditional media outlets throughout the country.

Kate Musgrave is the Assistant Research and Outreach Officer at the Center for International Media Assistance. Find her on Twitter at @kate_musgrave.

Comments (0)