Today is International Democracy Day: Thoughts on media’s role in democratic institutions

We’ve known for a long time that independent news media is a crucial ingredient in the mix of policies, institutions and political behaviors that make democracy work. And we’ve seen concrete examples of countries where the emergence of a strong, independent press has helped consolidate democratic institutions. Think of Poland, South Korea, Ghana, India, and, at various times in history, many others.

But as countries around the globe struggle to make democracies function more effectively, a growing body of evidence suggests that media may be more than just another optional ingredient in the democratic cake mix. It may be an essential or even causal ingredient that makes the whole thing rise or fall.

In recent years, for example, we’ve seen just how seriously the strongmen who run Russia and China take the news media. Grabbing control of the information flow and the means of distribution—broadcast, print and internet—has been a prime preoccupation in both countries, an area of huge government spending, and top-level strategic engagement by senior leadership.

Preventing the Downward Spiral

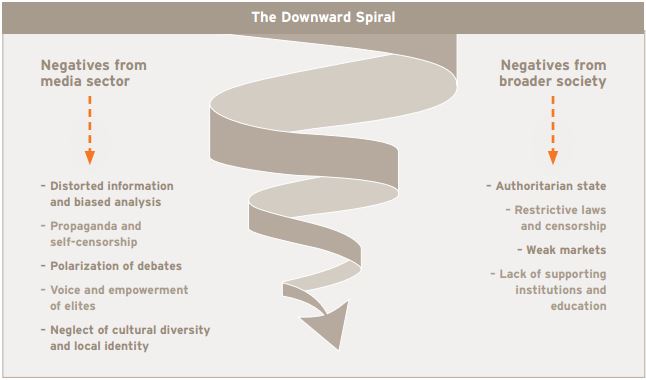

But in those countries where democracy still has a fighting chance, the media sector is often an overlooked and underfunded area of policy attention and political concern. And left to the devices of the nefarious elements of society, it can become a cancer that spreads to other areas of governance, creating a downward spiral that infects other areas of public policy, the rule of law, economic management, and political competition.

Over the past year, a partnership of CIMA and Deutsche Welle Akademie has been looking at the elements of the media environment and how these interact with broader elements of democracy and governance. In a recent paper, Considering the Dark Side of the Media, we developed a rough model that illustrates how media can magnify both positive and negative trajectories of countries, either helping them to improve governance and democracy, or in the worst cases, working against the any movement towards a functioning democratic system. The diagram above illustrates the downward spiral that my co-authors and I discuss in more detail in that publication.

CIMA and its partners are also looking at the politics of media reforms and asking what can be done to bring more attention to the media sector among parliamentarians and other decision-makers. That goes for building domestic coalitions for media reform at the country level as well as strengthening the resolve of international players to support those domestic movements.

Sleepwalking towards Capture

While non-democratic countries pursue deliberate and even violent campaigns to stifle the news media and bring it under control, other countries may be sleepwalking in the same direction through neglect and a lack of detailed knowledge about how to fashion the kind of media sector that benefits the common good. The international community—donors, the multilateral development banks, and foreign policy practitioners—should offer more help to countries are struggling to create a more effective media environment. Those countries need policy advice, and knowledge sharing about how media systems develop and about the best approaches to creating a diverse and successful media sector. Local civil society organizations and media advocacy groups need support for building stronger political movements that help people understand the importance of an open and professional media system that provides a diversity of viewpoints.

A large group of countries across the world fit into the category of emerging democracies where the media sector is woefully under supported by both domestic policy makers and by international donors. Examples include Indonesia; Romania, Ukraine and many others in Central Europe; Tunisia and Morocco; and Nigeria and many others in Africa.

This is not to say that building a strong and sustainable media sector is getting any easier these days. This process has gotten more complicated with the spread of social media, the global Internet and a traditional business model (independent news gathering funded mainly through advertising) that is faltering.

Yet the basic elements of a well-governed media system remain the same even in the emerging new media world. While freedom of expression is obviously a key factor, it requires a more complex array of public policies to ensure that the media performs in the interest of society. One of my favorite (and most concise) arguments—about the political-economy of independent media comes from Nobel prizewinning economist Joseph Stiglitz. In his 2008 article, “Fostering an Independent Media with a Diversity of Views” he lays out the basic institutional arrangements for such a media: access to information laws with an independent enforcement agency; a rigorous competition law to encourage diverse ownership arrangements and prevent monopolistic control over the media sector; laws that allow reasonable foreign entry into the media marketplace; creation of public service media; and other sector-level policies on tax, subsides and market access. The idea is that the media environment needs high quality policies that encourage a variety of players with diverse opinions.

Such a media will not only help countries create more effective economic systems, writes Stiglitz, it is “essential for the functioning of democratic political processes.”

We will be discussing these issues on September 30 at our offices in Washington, DC. RSVP.

Comments (0)

Comments are closed for this post.