By Andrea Vega Yudico

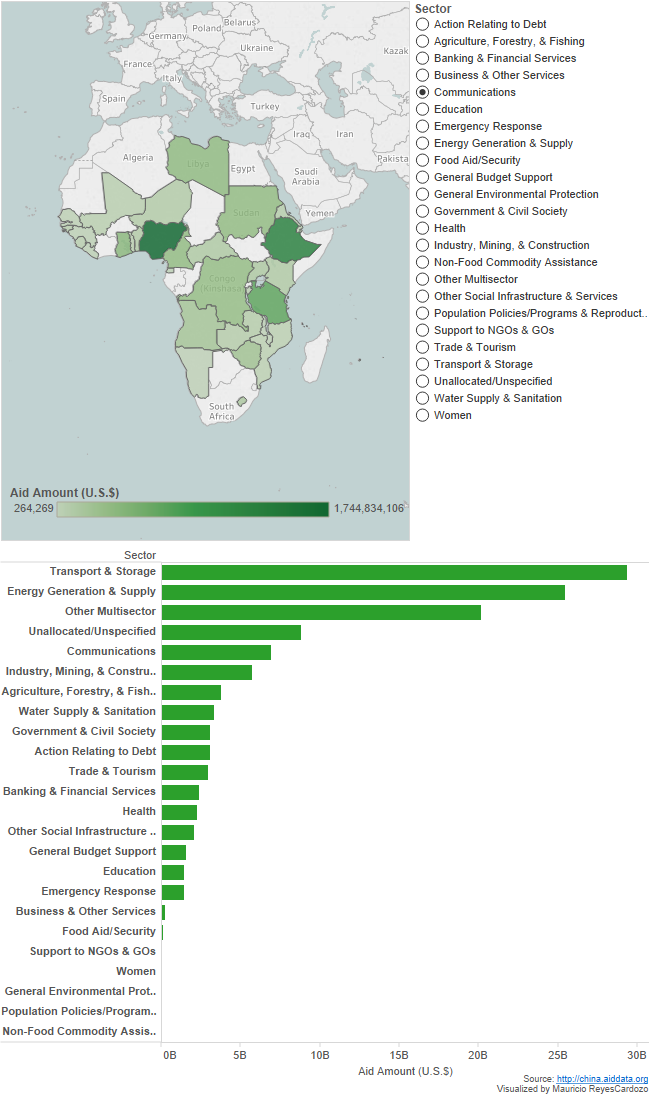

The Chinese government is making significant investments in telecommunications infrastructure across Africa. According to the Tracking Chinese Development Finance project at AidData, between 2000 and 2013, 38 African countries received $1.7 billion in combined Chinese investment. Of that total, the communications sector is the fifth largest sector to receive investment. Other estimates of Chinese investment are much higher, and it is impossible to know the true amount as the Chinese government does not publish these statistics.

In any case, these outlays are having an impact on perceptions of the Chinese government on the continent. According to a 2016 report by Afrobarometer, investments in infrastructure and business development contribute to popular perception by Africans that China is a “somewhat” or “very” positive influence in their countries. While investments in telecommunication infrastructure are much needed in many parts of Africa, African societies should be aware that Chinese technology and technical assistance may pose a long-term threat to individual privacy and media freedom. In the end, the Chinese development model is unlikely to help foster a thriving and independent media ecosystem – something countries need in order to enable long-term, sustainable and equitable growth.

Chinese Aid to African Countries by Sector, 2000-2013

The Digital Switch – Chinese Content to the Fore

One of China’s most common development investments in Africa has been to fund the digitalization of television. Chinese infrastructure providers have taken over provision of high quality and accessible television content in small rural towns where digital technology was once unattainable. The China Africa Development Fund and the China Development Bank have offered hundreds of millions of dollars in loans to fund the transition from analogue to digital. For example, in 2012, China loaned $30.6 million specifically to the Nigerian state of Kaduna in order to fund the shift from analogue to digital broadcasting. The larger objective was to strengthen the working capacity of the state television station, which is a distinct difference in approach from the broader media development field, which tends to favor supporting local, pluralistic, and independent voices. Indeed, in circumstances where media development donors and implementers do seek to strengthen the national public service broadcasters, they retain a strong commitment to editorial independence rather than strengthening the “state mouthpiece” model of state television.

In another instance, StarTimes, a private Beijing media enterprise with Chinese-government backing that operates in Kenya, South Africa, Nigeria, and Tanzania, is undertaking the transition to digital television with affordable television packages for only $4 a month that broadcast a mix of African and Chinese channels. However, as with any Chinese supported programming, state-directed editorial controls ensure that no material sensitive to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is included, while promoting material that favors the Chinese government’s strategic interests.

“Our aim is to enable every African household to afford digital TV, watch good digital TV and enjoy the digital life,” StarTimes Vice Chairman Guo Ziqi told China’s official New China News Agency in December. However, access in their television packages to international news channels such as BBC and Al-Jazeera cost more than what the average African can afford. Thus, while funding the transition to digital television on the continent, the Chinese government is also making sure that it increases access to China-approved media outlets.

Chinese Infrastructure Enables Surveillance and Censorship

China’s rapidly globalizing telecommunications investments also pose a threat to consumers’ privacy. As telecommunication systems grow in African countries courtesy of Chinese funds, it has been easier to identify threats posed to the media ecosystem on the continent. Reports by news outlet Zambian Watchdog conclude that China’s Huawei Technologies had installed email hacking devices on all ISPs in Zambia. Following an order from former president Sata authorizing the interception of telephone and Internet communications, the Zambian government contracted Chinese experts to install Internet surveillance and censorship equipment to monitor, censor and mine data from digital communications, according to Zambian Watchdog.

Huawei, an equipment manufacturer, is one of the largest contributors to Africa’s digital and mobile industry through smartphone distribution and network development. In 2012, a U.S. House of Representatives intelligence committee labeled the media giant Huawei a national security threat. Michael Chertoff, former U.S. secretary of homeland security, suggested that Huawei has potentially significant control and surveillance of African information networks via technological “backdoors.”

“There’s a great deal of concern about Huawei acting to advance the interests of the Chinese government in a strategic sense, which includes not only traditional espionage but as a vehicle for economic espionage,” former Department of Homeland Security secretary Michael Chertoff told Foreign Policy.

“If you build the network on which all the data flows, you’re in a perfect position to populate it with backdoors or vulnerabilities that only you know about, you’re upgrading it, each time you upgrade the network or service it, that’s an opportunity” to install spyware.

Huawei’s competitor in the African telecommunications industry is the Chinese telecom giant ZTE, whose equipment the Ethiopian government uses to monitor mobile technology. The Ethiopian government has used mobile surveillance to target ethnic populations, opposition activities and journalists, according to a report by Human Rights Watch.

Conclusion

Chinese-funded telecommunications investments have upgraded infrastructure and provided access to digital technologies in rural areas. However, there are critical surveillance-related and freedom of expression-related implications of Chinese assistance, particularly in countries where governments are eager for Chinese censorship and surveillance technologies. Civil society groups must remain vigilant, as these investments will shape the future of the media systems in which they live and operate – for better or for worse.

Andrea Vega Yudico is a third-year Journalism and International Studies student at Indiana University who has interned for publications in both China and Uganda.

Comments (0)

Comments are closed for this post.