Introduction

For most of its modern history, the news media in Ethiopia have been a tool for government control. But 2018 brought a wave of optimism to Africa’s second most populous nation. Anti-government protests forced the ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) to undertake major reforms to its authoritarian rule in an effort to stave off mass violence and the potential collapse of the central government.

The incumbent prime minister, Hailemariam Desalegn, was forced to resign. In his place, the EPRDF nominated Abiy Ahmed, a young and charismatic reformer from the long-marginalized Oromiya region. Overnight, protestors lifted roadblocks and popular discontent transformed into euphoria and hope for a better future.

This set the stage for one of the most remarkable attempts at media reform in sub-Saharan Africa in recent years. The Abiy government freed journalists from prison; deregulated the sector, enabling the establishment of dozens of new media houses; and put into motion a media reform process that brought government and civil society together in a shared vision for change. However, these early successes have faltered. Quick deregulation without strong enabling institutions and laws created a surge of media outlets and journalism associations that fueled polarization and conflict along ethnic fault lines.

Ethiopia’s civil society was also incapacitated by decades of authoritarian rule. International assistance actors, many of whom were not engaged in the country’s media sector prior to Abiy’s nomination, struggled to find local partners with the capacity to lead projects meant to professionalize the sector. In divided societies like Ethiopia’s, support for self-regulatory institutions and professional associations is key to promoting ethical standards and curbing hate speech and disinformation that is intended to sow discord.

Since November 2020, Abiy’s government has been consumed by a bloody civil war in Ethiopia’s northern Tigray region that has forced two million people from their homes. Tigrayan rebels, Ethiopian forces, and government-allied Amhara militia have all been accused of atrocities. In other parts of Ethiopia, the government struggles to maintain order amid outbreaks of violence among groups competing for land and other resources. As a result of this conflict, the government has retrenched on media freedom and adopted some of the repressive tactics of its predecessors.

Though the window for significant media reforms now appears closed, Ethiopia’s experience holds lessons for policymakers in other countries, as well as for international donors that can play a key role in supporting such reforms. This report, part of the Center for International Media Assistance’s “Media Reform amid Political Upheaval” series outlines the media reform process in Ethiopia since 2018, and examines the role of media assistance to advance the work of local advocates. Based on interviews with 16 media experts, this case study also explores the polarization of Ethiopia’s media and, finally, articulates key lessons from the country’s experience with media reform to date that may be applicable in the future.

Abiy’s Big Bang

In the months before Abiy Ahmed became prime minister in 2018, Ethiopia was a land in turmoil. Ethiopia’s two largest ethnic groups, the Oromo and the Amhara, had launched massive protests seeking better representation in an EPRDF government dominated since 1991 by Tigrayans, the country’s third-largest group. Helping fuel the protests were Oromo and Amhara nationalist social media groups that proved difficult for the government to censor.

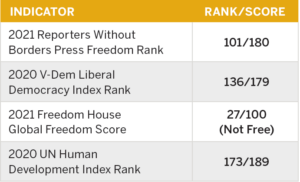

While ethnic polarization had been growing for some time, the issue was not widely covered by Ethiopia’s domestic media. Instead, the dominant broadcasters, all controlled by the state or ruling party, consistently emphasized national unity and downplayed ethnic conflict. Alternative news outlets were scarce as the government routinely jammed dissident satellite television stations as well as local language radio broadcasts by Voice of America, Deutsche Welle, and the BBC. Critical journalists and bloggers faced harassment, imprisonment, or exile for reporting on ethnic grievances, human rights abuses, or corruption. In 2017, Ethiopia ranked 150th out of 180 nations on Reporters Without Borders’ World Press Freedom Index, behind countries like Russia and South Sudan.

When Abiy, an Oromo, was elected prime minister of Ethiopia by the House of Representatives  in April 2018, it was widely seen as an effort by the EPRDF to diffuse the particularly volatile Oromo protests. But Abiy quickly showed his independence from the party’s authoritarian old guard and initiated a “big bang” of reforms.

in April 2018, it was widely seen as an effort by the EPRDF to diffuse the particularly volatile Oromo protests. But Abiy quickly showed his independence from the party’s authoritarian old guard and initiated a “big bang” of reforms.

Within weeks of taking power, he released thousands of political prisoners and journalists and apologized for the EPRDF’s past corruption and abuses of power. He warmed relations with Ethiopia’s longtime adversary, Eritrea, and exiled dissidents and rebel leaders were invited home. He moved to suspend the government’s state of emergency and lift an anti-terrorism law that had been used to prosecute journalists and opposition figures. His government dropped criminal charges against two US-based satellite news broadcasters and lifted the internet blockage of more than 260 websites. Dozens of new media outlets sprang up. Abiy’s domestic and international standing skyrocketed, and in 2019, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. By 2020, Ethiopia had jumped 51 places on the World Press Freedom Index, ranking 99th out of 180 countries.

Donor Decisions

As early as mid-2018, it was clear that an extraordinary window for media reform had opened. For media assistance actors this was a rare opportunity. Although Ethiopia was one of the world’s largest recipients of humanitarian aid under the EPRDF, the government was historically hostile to foreign media assistance and other governance- and democracy-related programs. Abiy’s reforms were so swift and unexpected that many media development organizations were caught unprepared: Few had experienced staff, ready resources, or strong local partners. As a result, despite timely commitments by international donors to support Ethiopia’s reform, there were long delays in developing and funding programs.

In part, this was due to the volatile security situation in the country. In June 2018, Abiy survived an assassination attempt at a rally, and ethnic violence returned to the Oromiya region near the capital. However, delays were also caused by media assistance actors trying to get a handle on the rapidly changing media environment. According to a representative of a media development nongovernmental organization (NGO), no fewer than 19 media sector studies and assessments were conducted in Ethiopia in 2018.1

As many media development organizations were preparing to conduct needs assessments and design and launch projects, the window for reform had already closed. By 2019, the government’s reform momentum waned as Abiy’s relations with his Tigrayan partners in the ruling party worsened. The start of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020 led to further delays, and by November of that year the government’s focus was not on political reforms but the outbreak of civil war in Tigray.

Not all media development organizations were slow to act. An initiative by Sweden’s Fojo Media Institute and Denmark’s International Media Support began capacity building for journalists’ associations in 2019, while supporting the establishment of the Editors Guild of Ethiopia and Community Radio Broadcasters Association. Similarly, Deutsche Welle Akademie and Open Society Foundations funded media projects in time for them to have an impact during the reform window. In addition, organizations including the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the Open Society Initiative for Eastern Africa, and the National Endowment for Democracy provided funding to help advance the enabling environment for the media, including legal and regulatory reform processes.

After the announcement of Abiy’s Nobel Peace Prize, a number of additional donors and international media development NGOs began work in Ethiopia. Yet there was no mechanism to coordinate the efforts of the various groups and, as a result, opportunities for synergies were lost. In November 2019, UNESCO, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, attempted to create a coordination platform for Ethiopian and international media nonprofits. Unfortunately, this effort failed to get off the ground as it did not have bottom-up support and Ethiopian media civil society lacked the capacity to participate and lead it.

This highlights another weakness in the response. During the first three years of reform, international donors made commitments to fund public interest media, legal and policy reform efforts, and the professionalization of the sector. Much of this financing focused on implementing specific projects, such as workshops for journalists. However, in Ethiopia, where the EPRDF effectively decimated independent media associations and curbed the institutional growth of media outlets, there were few local partners with the institutional capacity to manage substantial projects.

Building the capacity of core institutions should have been paramount, as low-capacity civil society groups struggle to design and implement effective programs. Civil society organizations, such as journalists’ associations, need support to develop organizational capacities and policies to manage grants and human resources. But this was largely missing in the early reform period. Two years after its founding, the Editors Guild of Ethiopia lacked both office space and staff and was fighting to stay afloat.

Reforming Laws and Policy

International donors did help catalyze some initial momentum for media reform in Ethiopia. After the initial “big bang” of reforms, Abiy’s government embarked on an ambitious intermediate-term reform process. The goals were not only to change laws that govern the justice system, the media, civil society, and other institutions of democratic governance, but to reform the state structures shaped by decades of authoritarian rule.

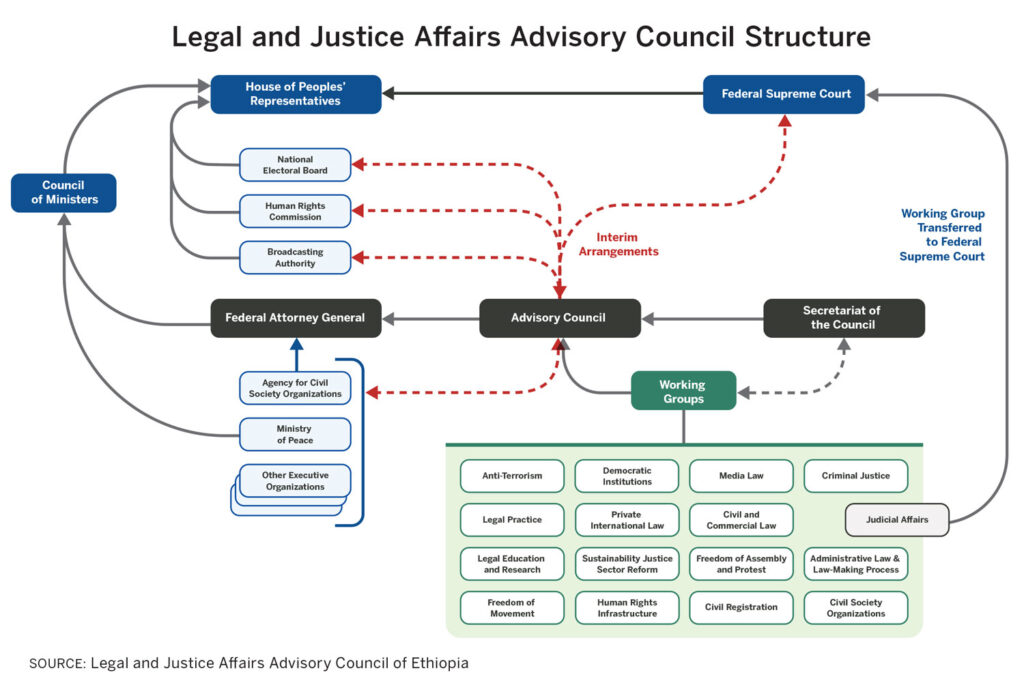

To do so, the government appointed an independent panel of high-profile lawyers, academics, and human rights advocates from outside government with a three-year mandate to develop proposed reforms. This body, known as the Legal and Justice Affairs Advisory Council (LJAAC), oversaw 14 working groups that focused on specific issues, such as media law, anti-terrorism law, and human rights infrastructure.

With funding from UNDP and other donors, working groups held stakeholder and public meetings where comments were incorporated into draft laws. After the drafts were approved by the LJAAC, proposed bills were relayed directly to Abiy’s Council of Ministers for presentation to the parliament. This bottom-up approach garnered praise for its inclusivity as well as its independence from both donors and, importantly, the Ethiopian government itself.

The LJAAC’s Media Law Working Group, a group of 14 journalists, activists, and legal scholars, used this format to make notable progress. In September 2018, the government made an unprecedented move in calling on a group of independent journalists, media managers, civil society groups, and government regulators to design a consultative assessment that would serve as a basis for the country’s first written media policy.2 Given Ethiopia’s history, it was remarkable that such a document would be produced with the input of civil society advocates and independent journalists rather than simply handed down by the government. The tone of Ethiopia’s reform process was set early: Stakeholders from outside government and state media were to be centrally involved in shaping the future of Ethiopia’s media.

This process led to the parliamentary approval of Ethiopia’s landmark Media Proclamation in February 2021. The new law came about only after the Media Law Working Group conducted 23 consultations with journalists and other stakeholders in Addis Ababa and regional towns.3 Among other provisions, the new law decriminalized defamation, banned political ownership of media, made public media accountable to parliament, gave clear mandates to an independent media regulatory agency, and provided a non-statutory framework for media to self-regulate.

Though the Media Proclamation is the most tangible success of the Media Law Working Group, the body has also laid the groundwork for reform in two other areas. Work on a new Freedom of Information Proclamation is underway, which would give existing laws teeth by creating a new enforcement mechanism to ensure government officials produce documents as legally required. Separately, the group is working to reform a 2016 Computer Crime Proclamation, which gave the government vast surveillance powers and granted prosecutors broad latitude to criminally prosecute those who “incite fear” online.4

Ethiopia’s Media Today

The rapid opening of Ethiopia’s media space had unexpected consequences. Diaspora media based in the United States and Europe, notably the Oromo Media Network (OMN) and Amhara Satellite Radio and Television (Asrat TV), were allowed to operate freely in the country and rapidly gained audiences for their ethno-nationalistic reporting. A second effect was the change in the editorial policy of outlets owned by regional governments. Rather than reinforcing messages of national unity and praise for the central government as in years past, these outlets often used their newfound independence to advance narratives particular to their ethnic group.5

This environment led to the growth of hate speech, both in broadcast and social media. An example highlighted in a recent report by the Fojo Media Institute is an OMN broadcast in which a woman interviewed during a demonstration called for Oromo men to divorce their Amhara and Tigrayan wives.6 Online, a 2019 study from Addis Ababa University found that as many as 95 percent of social media posts about ethnicity and religion in Ethiopia contained hate speech.7

This evolution has now caused the primary distinction in Ethiopian media to change. No longer is it between the government-controlled press and a relatively small number of privately held, independent media outlets, but among the ethnic identities of media outlets and mass media agencies. As noted by the Fojo Media Institute, this climate shapes how journalists work and advocate for themselves. Travel to some parts of the country is now dangerous for journalists, and many of them have organized into new ethnic journalism associations such as the Amhara Journalists Association, the Oromia Journalists Association, and the Tigray Journalists Association.

Media ownership exacerbates this situation. The majority of Ethiopia’s legacy broadcast media are owned and operated, either directly or indirectly, by the ruling party or its regional affiliates. Contending political actors control much of those remaining, leaving little space for independent media. Whether the new Media Proclamation’s restrictions on political ownership of media are meaningfully implemented remains to be seen.

The Ethiopian government’s commitment to reform has diminished and initial optimism has waned. Since the war in Tigray began in November 2020, the government’s backsliding on press freedoms has accelerated. Journalists and media workers have been arrested en masse on multiple occasions.8 In January, a reporter in Tigray was shot and killed, reportedly by Ethiopian security forces. In February, security agents ransacked the home of Lucy Kassa, a freelancer for the Los Angeles Times, and threatened her. In May, an Irish journalist who reported on government atrocities in the Tigray region for the New York Times was expelled.

Lessons for the Future

This leaves Ethiopia at a critical juncture, with highly polarized political, social, and media spheres fomenting violence, both in Tigray and in unrelated conflicts elsewhere. The government is increasingly turning to repressive measures to control the media amid a stalemated civil war. While the current outlook for reform is grim, Ethiopia’s experience holds lessons for policymakers, donors, and media development organizations operating in similar contexts.

One takeaway from Ethiopia is that donors need to be prepared in advance of reform windows so they can act quickly when they arrive. In Ethiopia’s case, too little support was provided to media reform efforts in the first 12 to 18 months after Abiy’s accession when it could have made the most impact. Further, in societies emerging from decades of authoritarian rule, donors should support core institutional capacity building for media-based civil society so that new and fledgling organizations have adequate staff, resources, and professionalism to execute and lead a media reform vision.

Second, the speed of Abiy’s early liberalization provided new space for political debate but also resulted in a media market that quickly fragmented along ethnic lines. Such reforms should be conducted in tandem with support to strengthen the regulatory and enabling environment for the media, including policies and institutions to govern and safeguard the new sector.9 Key to this is enforcement of rules limiting the political ownership of media and protections to ensure that outlets operate independently and in the public interest, rather than as cheerleaders for a particular political faction or ethnic group.

Third, the sustained engagement of independent journalists, academics, activists, lawyers, and other stakeholders from outside government in the reform effort is vital. However, such engagement needs to continue after the drafting of new media codes and directives so that enactment is not left solely to the government in a post-authoritarian state.

Finally, the absence of effective monitoring mechanisms for hate speech and misinformation were major challenges in Ethiopia, as they have been in numerous other transitional countries. This problem is particularly thorny in a post-authoritarian state like Ethiopia, where legitimate opposition figures have historically been charged with terrorism or inciting ethnic hatred. That history leads to suspicion of government efforts to curb such speech in the media. Addressing it requires a range of solutions, including the cooperation of social media platforms, improved capacity of media organizations to identify and debunk mis- and disinformation, and better understanding by government agencies of how to balance protecting peace and security with enabling free and vibrant speech and political debate.

Header Photo Credit: Str/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock

To read the working paper for this case study, as well as the synthesis report and the other country case studies, please see the project landing page here.

Footnotes

- Tewodros Negash, in an interview with the author, March 2021.

- Ethiopian Government Media Policy 2020, available at: https://www.ema.gov.et/web/guest/%E1%8B%A8%E1%88%98%E1%8C%88%E1%8A%93%E1%8A%9B-%E1%89%A5%E1%8B%99%E1%88%83%E1%8A%95-%E1%8D%96%E1%88%8A%E1%88%B2 (only in Amharic).

- Solomon Goshu, Chair of the Media Law Working Group, in an interview with the author, March 2021.

- “Ethiopia: Computer Crime Proclamation: Legal Analysis,” ARTICLE 19, July 2016, https://www.article19.org/data/files/medialibrary/38450/Ethiopia-Computer-Crime-Proclamation-Legal-Analysis-July-(1).pdf.

- Terje Skjerdal and Mulatu Alemayehu, “The Ethnification of the Ethiopian Media,” (Addis Ababa: Fojo Media Institute and International Media Support, February 2021).

- Ibid.

- Mulugeta Abrha, “Mapping Online Hate Speech among Ethiopians: The Case of Facebook, Twitter and YouTube,” (Addis Ababa: Addis Ababa University Graduate School of Journalism and Communication, June 2019), http://etd.aau.edu.et/bitstream/handle/123456789/18880/Mulugeta%20Abrha.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- “Eighteen Journalists Arrested in Ethiopia, Two Facing Possible Death Sentence,” Reporters Without Borders, June 3, 2022, https://rsf.org/en/eighteen-journalists-arrested-ethiopia-two-facing-possible-death-sentence; “RSF Decries Wave of Arrests in Ethiopia,” Reporters Without Borders, July 12, 2021, https://rsf.org/en/rsf-decries-wave-arrests-ethiopia.

- See also Mark Nelson and Heather Gilberds, “Confronting Hard Truths: Media Reform in Fragile Societies,” (Forthcoming).