Introduction

When global media brands and digital social media platforms enter markets, especially markets with little indigenous media capacity, they can greatly expand the amount of news and entertainment for citizens. The entire market for media expands—but not without a cost. National and local news is increasingly a casualty of globalized media markets.

Al-Jazeera’s international expansion, Facebook’s growing importance to citizens in the Global South, Disney Channel Worldwide’s farreaching distribution network: these platforms and others have brought audiences around the world more content than ever. But these platforms also bring with them a restructuring of advertising markets that can favor government-funded state media or entertainment platforms over smaller outlets offering national and local news. Simultaneously, the ubiquity of mobile platforms has made them key vectors for transmitting news in real time using social media. In countries with otherwise limited media channels, mobile plays a dominant role. 1 Facebook, WeChat, and others are leading channels for distributing news, user-created content, and commentary. While this has many positive outcomes, it also facilitates the spread of pro-government messaging, propaganda, misdirection, and hate speech. 2 Moreover, when independent news content appears on social media platforms, it is often the platform that harvests the revenue, not the content provider, further eroding the financial base for local and national reporting.

Often vulnerable are the independent news media operating in restrictive environments, along borders of closed countries, or in exile. Similarly, they are often the least-resourced news providers and exist outside of mainstream advertising marketplaces. Internally, they frequently lack the data to make good decisions about matching content to audiences and—focused on their social missions—may lack the will or motivation to do so. Yet the failure to engage with broad audiences on a regular basis shuts them off from sources of revenue.

Thus, in a world where people can feast on an unlimited buffet of media choices, there is an increasing famine of credible, thorough, and independent nationally-focused news reporting. The former masks the latter as people worldwide now have access to an unlimited amount of entertainment through a wide variety of channels and as governments exert more comprehensive and nuanced control over media. Better connected globally, but less informed locally, citizens living in these media environments may not recognize when their rights to be informed about their government and their society are being compromised.

This report looks at ten factors that have altered the media marketplace and that pose challenges to national and local news producers and their sources of revenue. They include ways in which governments interfere in media markets; changes in the structure of news distribution and audience behavior; and the way these changes have transformed how advertising media is bought, sold, and distributed. It then examines the key engagement metrics taken from a sampling of media development partner organizations to offer thoughts on how well these news producers are prepared to compete for audiences and revenue. Finally, it offers thoughts about the implications of these issues for media development organizations.

Ten Factors Affecting Independent News Media

Factor #1: Independent media are captured and replaced with entertainment

Around the world, there has been a marked deterioration in press freedoms in recent years, threatening the survival of independent news coverage in some areas. Reporters Without Borders cites a number of risks to press freedom in the most recent World Press Freedom Index, some old and some new. Journalists continue to be attacked and murdered for their work and charged for spurious crimes such as “insulting the president” or “blasphemy,” while several governments have reasserted controls on state-owned media. Armed conflict, the spread of ideologies hostile towards journalism, and deteriorating security situations in numerous countries have also threatened the ability of journalists to perform their professional duties. 3

Simultaneously, independent journalism faces more sophisticated techniques of suppression. Taking advantage of the challenge to journalistic business models created by digital media, authoritarian states are building new, modern-day propaganda machines. Meanwhile, “throughout the world, ‘oligarchs’ are buying up media outlets and are exercising pressure that compounds the pressure already coming from governments.”4 These combined forces lead to a capture of media that distorts the entire media landscape “where political leaders and media owners work together in a symbiotic but mutually corrupting relationship.” 5

Captured media does not have the same complexion as Soviet-style censorship; on the contrary, captured media often dazzle audiences with high-quality entertainment and even with glossy news productions—but with an emphasis on the sensational and scandalous, and without the critical content citizens need to hold their governments to account.

Unfortunately, there are many examples.

In Serbia, the recent privatization process resulted in the capture and consolidation of more media. It fueled the rise of entertainment and reality programming at the expense of journalism. Minority and independent provincial media became starved for revenue. B92, the bold independent radio station known for its opposition to Slobodan Milošević, retreated from its critical position and changed to an entertainment format. The media sector in 2015 was “characterized by the collapse of law, ethics, professionalism, and social norms.” 6

In Turkey, dramatic changes in the ownership of media organizations have all but eliminated senior figures in the news industry who are willing to publish stories critical of the ruling government. The results of this capture was laid bare in October 2011, when then Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan (now President) summoned a group of 35 senior media figures to orchestrate the censorship of news about a cross-border attack by the Kurdistan Workers Party from Iraq. The attendees obliged the request without any resistance, according to an account of the gathering that was later published by one of the few openly critical newspapers. 7

Both China and Russia have actively limited access to journalism (whether by censorship or economic pressure) while serving up a vast assortment of politically encoded entertainment media that has high-quality production values and compelling content.

In February 2016, Chinese President Xi Jinping toured the country’s major newsrooms telling reporters and editors in no uncertain terms that their job, first and foremost, is to serve the Party. A subsequent editorial in Xinhua noted “according to Xi, managing journalism and publicity is ‘crucial for the Party’s path, the implementation of Party theories and policies, the development of various Party and state causes, the unity of the Party, the country and people of all ethnic groups, as well as the future and fate of the Party and the country.’” 8

And now both China and Russia are making efforts to extend their influence over media outside their borders.

For example, the Chinese government has made tremendous efforts to influence global media through a combination of market-oriented mechanisms, propaganda and pressure tactics. 9 Chunwan, the annual program celebrating the eve of the Spring Festival, reaches an estimated 900 million viewers worldwide. China Central Television (CCTV) has built a vast and well-funded news network around the world with more than 70 international bureaus, including major global offices in Beijing, Nairobi and Washington, DC. Broadcasting in local languages as well as Chinese, CCTV has hired reputable journalists to provide independent coverage, but with editorial limits imposed on stories with political relevance to China. 10

In the Russian language space, Kremlin-aligned media, including those owned by commercial entities, dominate. Their Moscow-centric programming offers high production values, prolific choices, narratives that evoke nostalgia for the Soviet past, and anti-Western viewpoints. Talk shows and reality shows feature wildly popular stars. Shows focusing on Russia’s role and perceived victimization during World War II are common. More than 850 sitcom series (not individual shows, but entire multiepisode series) were produced during 2015. 11

In aggregate, these moves both limit audience access to national and local news reporting while concealing the absence with an abundance of other content. Ross Settles, an expert on digital media and consultant for the Media Development Investment Fund (MDIF), worries that audiences in these environments “may not be able to distinguish between quality journalism and good production values.” 12

Factor #2: Many audiences have switched to digital, especially on mobile

These ramped-up efforts by governments to promote self-serving agendas and limit access to independent and factual reporting are occurring at the same time that major secular changes are reshaping how audiences consume media, and how journalism is funded—with the continued viability of advertising as the key source of revenue for news media coming into question.

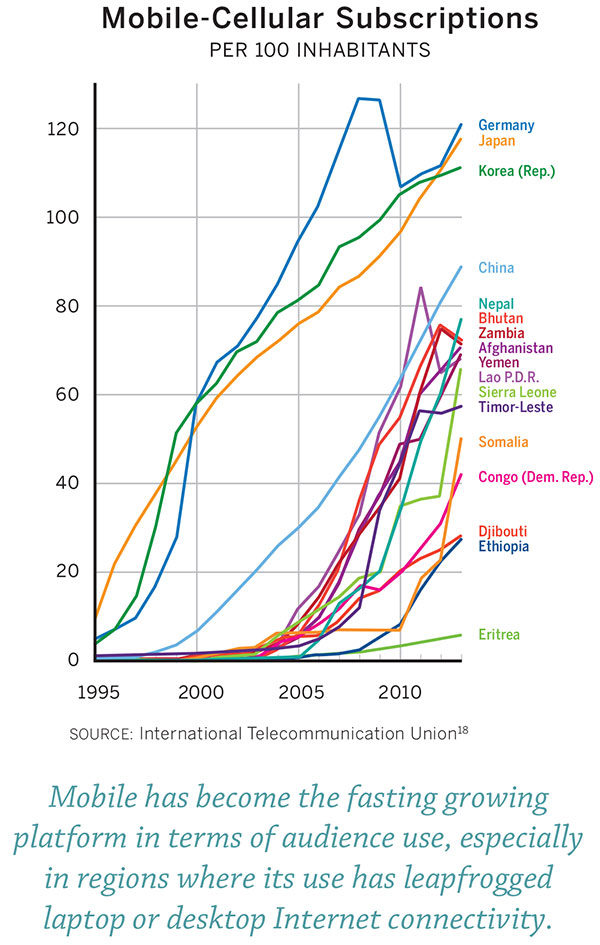

Most significant in the growth of digital media is the near ubiquitous presence of mobile, even in countries that otherwise have limited Internet access. Mobile has become the fasting growing platform in terms of audience use, especially in regions where its use has leapfrogged laptop or desktop Internet connectivity. There is ample evidence of how, where, and when audiences use media, including the rise of social media as a preferred news channel.

Pew’s State of the News Media 2016 takes an in-depth look at audience behavior in the United States. 13 Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism produces its annual Digital News Report that examines current issues affecting news media. 14 Mary Meeker’s annual report on Internet trends provides powerful insights into the trends surrounding digital media. 15 GSMA, an organization representing the interests of mobile operators worldwide, shares deep data on mobile use and the relative connectivity of countries through its GMSA Intelligence site. 16

The International Telecommunication Union (ITU), the United Nations’ agency dedicated to gathering data on information and communication issues, reports that seven billion people, or 95 percent of the world’s population, live in an area covered by one or more mobile networks and that more than half of the world’s population has a mobile phone. Even in least developed countries, which still lag their more developed counterparts, mobile penetration has grown rapidly during the last five years. 17

Factor #3: Mobile penetration is setting the conditions for an even greater shift

That said, mobile phone penetration is not a proxy for Internet penetration, but it is often its forerunner, and the potential for an even greater shift by audiences to digital is enormous.

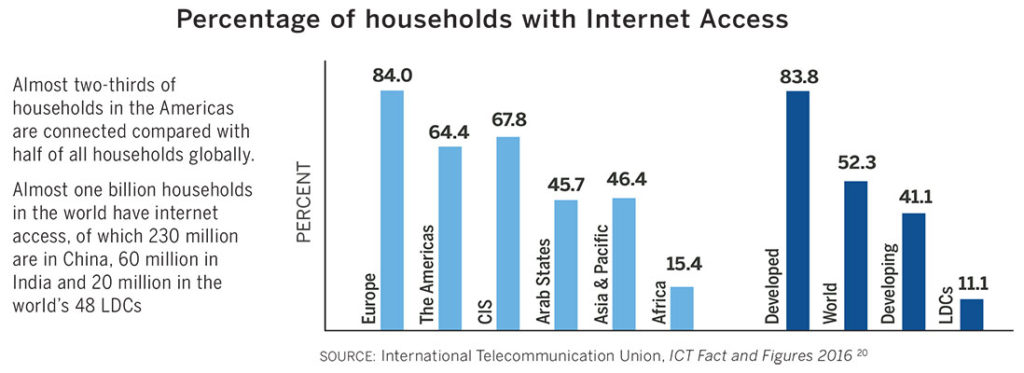

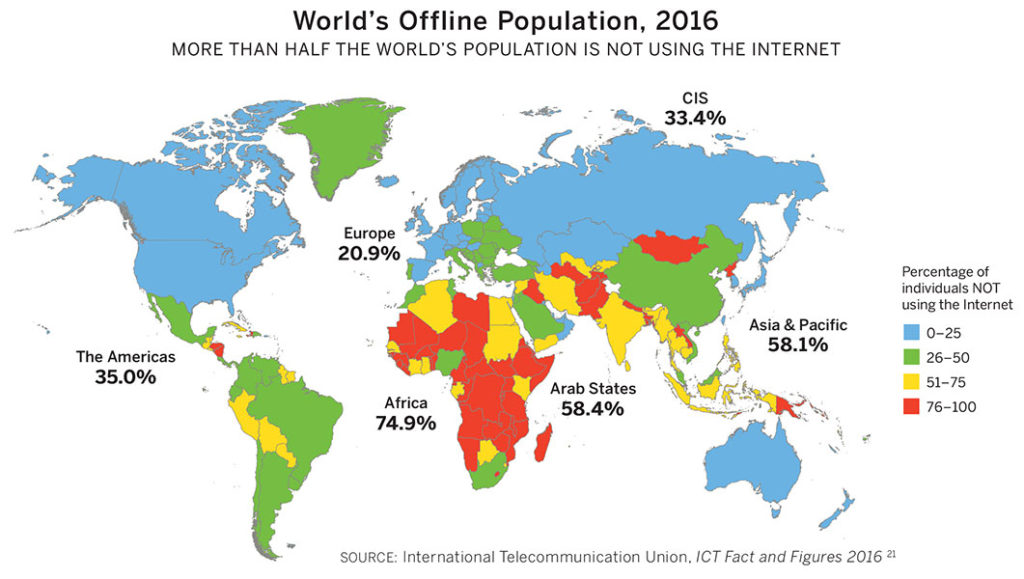

ITU’s data show that “by the end of 2016, more than half of the world’s population—3.9 billion people—will not yet be using the Internet. Figures for household access reveal the extent to which this digital divide remains geographical: 84 percent of households are connected in Europe, compared with 15.4 percent in the African region.” 18

When mapped, the differences in Internet access between the Global North and South are apparent. But while such inequalities in Internet penetration are indeed a reminder that the trends highlighted in this report have occurred unevenly, the remaining inequalities can also be viewed as the potential for these trends to spread and intensify. The Free Basics program currently being piloted in Nigeria by Facebook suggests that the Internet giant, for one, sees the digital divide as more of an opportunity than an obstacle. Free Basics aims to be a Facebook-centric, stripped down version of the Internet made available at no charge through partnerships with mobile service providers. The Free Basics service has been criticized elsewhere for providing a platform that could be easily controlled by authoritarian governments, 19 but if initiatives such as Free Basics succeed in expediting the shift to digital media in these areas, local news producers may merely be suppressed by the dynamics of the digital advertising market.

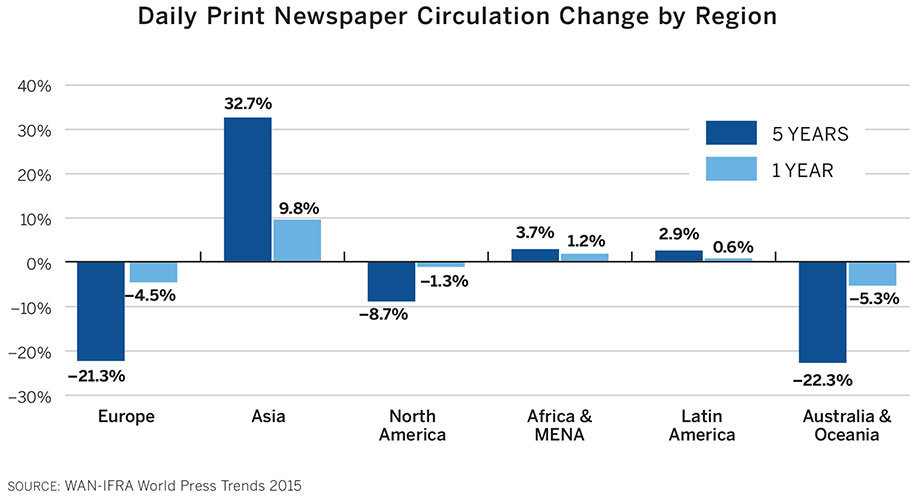

It is an often overlooked fact that in areas where Internet access is limited, or where newspapers exist in vernacular languages, newspaper circulation has increased in recent years. The largest gains have occurred in Asia, primarily in India and China, followed by more modest increases in Africa and Latin America. WAN-IFRA succinctly summarizes its data with the declaration that “Print circulation rises in East, sets in West,” and notes that increased literacy and economic growth in those areas have fueled its expansion. 20 Whether these bright spots of growth in national and local news media can be sustained, however, may depend on whether media houses are prepared for, or somehow protected from, the disruptive effects of the shift to digital and mobile.

Factor #4: Advertising revenues have followed audiences

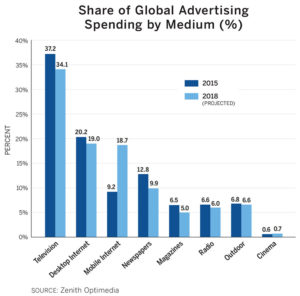

While television has long been the primary advertising vehicle worldwide, Zenith Optimedia, which tracks annual global and regional advertising spending by medium, forecasts that Internet advertising revenue (desktop plus mobile combined) is expected to surpass the amount spent on television during 2017.

Of total global advertising expenditures of $579 billion in 2016, Internet advertising was the main source of growth. Internet advertising, on desktops and mobile devices, is growing three times faster than advertising on other media channels, increasing 15.7 percent in 2016 fueled by increases in social media (31.9 percent), online video (22.4 percent), and paid search (15.7 percent).

Mobile advertising (which can include all three of these as well as traditional display advertising) is the fastest-growing component of internet advertising. It is expected to achieve a phenomenal growth rate of 32 percent per year between 2015 and 2018. 21

These increases in internet advertising, whether on mobile or desktop platforms, have come at the expense of print, which has experienced audience declines in many parts of the world. While internet advertising has grown from 6% to 29% of global ad spend between 2005–2015, newspapers’ share has fallen from 29% to 13%, and magazines’ share has declined from 13% to 6%. 22

This fast rate of change in ad spending will likely accelerate. Currently, ad spending has yet to catch up to “eyeballs,” meaning that there is a lag time between where ad budgets are allocated and where audiences are active. Once the advertising infrastructure is fully aligned to deliver more and better advertising into the digital environment, expect the shape of these spending patterns to alter significantly.

What these data fail to fully show, however, is the synergistic relationship between some of these different platforms. Television’s losses in share of advertising (even as television advertising revenue grows, it is expected to receive a lower percentage of overall advertising) will be driven by increases in paid search advertising, for instance; one is a brand awareness medium, the other a direct marketing channel, and they are powerful when combined in well-coordinated campaigns. And audiovisual advertising, when looked at as a whole (television plus online advertising), is growing rapidly. 23 Conversely, stand-alone platforms, those that lack synergies with the other parts of the advertising environment, are at risk of being excluded.

Factor #5: Fewer, bigger players are capturing a huge part of the pie… and there is one dominant player

What do these changes look like when viewed through the lens of where the money is going?

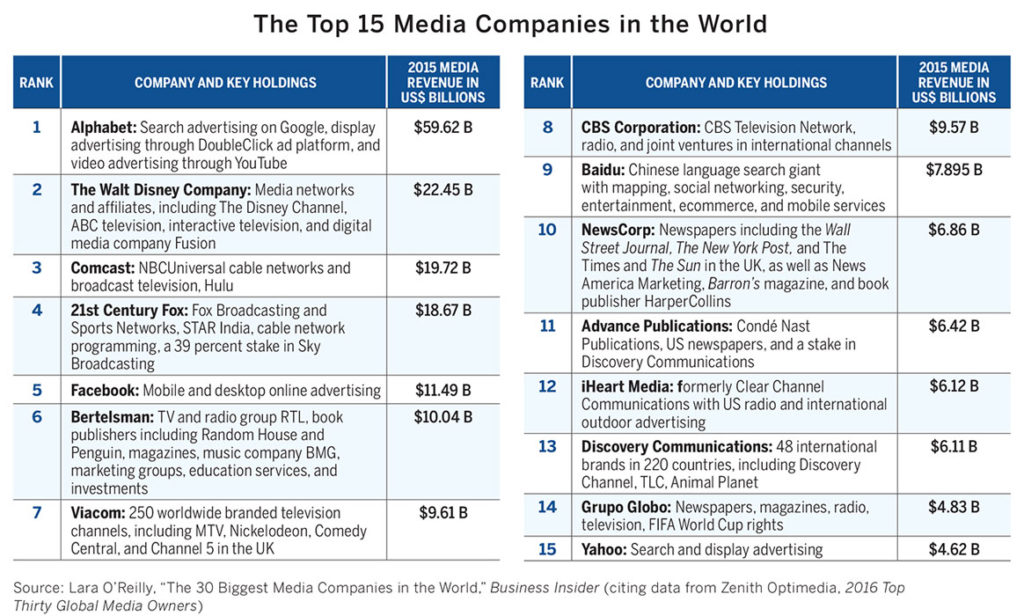

A review of publicly-traded companies shows that 30 companies are generating $257.12 billion in media-derived revenue, according to Zenith Optimedia’s 2016 “Top Thirty Global Media Owners” report. 24 These revenues are not directly comparable to the amount of global advertising spending, as they include other income such as newspaper and magazine subscriptions, but they clearly show that digital giants and diversified media companies now dominate the global advertising market.

Notably, Internet media have come to the fore, with Alphabet (the parent company of Google) having become the largest media company in the world—and by a large margin. In 2015, so-called “pure-play” digital platforms gained momentum: Google, Facebook, Baidu, Yahoo, and Microsoft together captured 19 percent of total advertising flowing through all forms of media. Moreover, most of the major content producing companies have global distribution strategies. They have consolidated under a number of powerful players with holdings in diverse areas that allow them to cross-market and leverage their holdings. Readily available branded media content now crosses borders, and brings global and regional advertising with it.

For example, Disney Channels Worldwide has a global footprint that brings the Disney brand to more than 600 million viewers. Its portfolio of entertainment channels and/or channel feeds that allow users to livestream content is available in 163 countries and territories, produced in 34 languages, and distributed across six platform brands (Disney Channel, Disney Junior, Disney XD, Disney Cinemagic, Hungama, and Radio Disney). It uses cable, satellite, and digital terrestrial television channels to distribute content, has multiple mobile strategies, offers subscription video-ondemand, and has produced content-rich broadband websites. 25

ESPN, the global sports powerhouse (and 80 percent owned by ABC, a subsidiary of The Walt Disney Company), reaches more than 61 countries and territories around the world. It is present on all seven continents and operates entities that are involved in television, radio, print, Internet, broadband, wireless, merchandising, and events.

The high-production-value content from these media giants is deeply appealing to audiences and often outshines national and local offerings. And their distribution channels also offer major brands powerful and efficient ways to connect with potential consumers. Local audiences prefer them; local media find it difficult to compete with them.

Factor #6: Ubiquitous, high-quality media compete for attention in an expanding world media market

While news media companies lament the diminishing advertising revenues in legacy media and insufficient growth of revenues online, global advertising is expanding, and rapidly. This is driven by major companies offering branded content—and the ability of audiences nearly everywhere to get that content in digital formats and real time.

McKinsey & Company, in its annual review of the larger media industry ecosystem, estimates that global spending on all media will rise at a compound rate of 5.1 percent between 2014 and 2019, reaching $2.1 trillion during that time. The estimate takes into account not only digital and legacy advertising, but also spending on broadband and mobile Internet, in-home entertainment, audio entertainment, cinema, video games, books, and educational publishing. They see the total media market expanding because of the growth in digital and the economic expansion of emerging markets. 26 McKinsey also observes that all media, not just news media, are shifting towards digital delivery.

“By 2019, we believe digital spending will account for more than 50 percent of all media spend…. This rapid digital shift is being driven in part by the growing number of connected consumers, the expansion of mobile telephony, and elevated mobile broadband adoption. As it continues, it will not only expand the digital share of the media wallet, but have a structural effect on almost all media sub-sectors, redefining business models. For example, we see a growing move away from ‘bundled’ media, such as that offered by traditional cable TV, to what might be termed ‘self-service re-bundling’—consumers picking and choosing from a variety of online streaming services to create their own, more streamlined personal programming bundles.” 27

Factor #7: As advertisers follow audiences to digital, the advertising industry’s architecture has been reshaped

Collectively, these trends and business strategies have fundamentally altered how advertising is bought and sold. They have fueled the rise of consolidated advertising placement, which is now organized and managed by major ad agencies and facilitated by a wide number of intermediaries.

In that environment, the world’s largest advertising agencies have consolidated and deepened their ability to deliver advertising across these diverse platforms, with holdings that deliver creative services, digital marketing, media placement, marketing and data services, and public relations. They have strong representation in mature and emerging markets and can deliver integrated marketing services to their clients.

These huge omnibus marketing groups have enormous clout across many fields. For example, WPP, the world’s largest marketing holding company, recently purchased the research firm comScore in order to improve the metrics associated with digital and mobile marketing. It owns a vast assortment of well-known brands in research, creative, and marketing services. The company seeks not just vertical integration in these areas, but horizontal integration across the marketing spectrum. Geographically, it has forged alliances and made acquisitions in national and regional markets throughout the emerging world to capture market share as those countries open, and their economies expand.

WPP and the other major marketing groups thus quickly inject best practices into the markets they enter and bring them into the global advertising ecosystem.

These types of changes make consolidated ad buying easier on the one hand, and more effective on the other. The changes also open avenues for global and regional advertisers, allowing them to participate in new and growing markets. Locally, it brings enhanced credibility and market power to the local partners of these huge firms.

However, what it does not bring is a commitment to supporting media plurality within local communities. Or ad buys. As a result, the consolidation of marketing expertise among global players does not typically benefit independent local news providers. Since ad targeting can be done at an individual level in digital media, national or other geographic boundaries lose some relevance. Agencies can place buys in “spillover markets,” where the media from a larger country flows into a neighboring one, obviating the need to purchase local market advertising.

Too often, the smaller independent news organizations are also simply invisible within this system. They are amateurs. If a local media house lacks data, does not have a compelling message about its audience, or fails to dominate in one or more segments, it is unlikely to be included in a significant media buy. Moreover, many of brand advertisers actively seek to avoid controversial news media. They prefer messages be presented in “brand neutral” environments and particularly seek to avoid associating with photos of conflict, dead bodies, violence, or catastrophe.

The global advertising industry is concentrated among a small number of key players with vast horizontal holdings delivering creative services, digital marketing, media placement, marketing and data services, and public relations. Smaller independent media houses are often non-players in this growing ecosystem.

Factor #8: Advertising placement is driven by data, not deals

Data drives marketing strategy—huge amounts of data. The CEO of the marketing giant WPP, Sir Martin Sorrell, acknowledged this reality as he predicted the company’s decision to acquire more data capacity.

“… Our business will become more scientific and data-driven. It’s certainly getting easier to define the target market, to know who’s watching or listening or responding to whatever messages you’re sending, and to measure the effectiveness. We invested in a company with 2,700 software engineers in Latin America. Ten years ago, if you had predicted we’d do that, I’d have said you needed your head examined. Research, plus direct marketing and digital—well over half of our business is scientific or science-related. The rest is what you might call pure art and big ideas. Our competitive set is no longer Omnicom and IPG and Publicis. It is Nielsen and GFK. It’s the data companies.” 28

This is changing the overall professionalism of advertising and marketing. The clients investing in marketing communications demand proof that their messages are reaching the right people, the right way, and having impact. It also brings international standards to bear on smaller markets that may be unfamiliar with those practices; for example, using big data to guide strategy, requiring proof of performance reporting, and using engagement and response metrics to evaluate campaign success.

These practices challenge media organizations that primarily operate as newsrooms rather than business institutions, and often lack data. It also challenges media that have relied on one-off agreements, price discounting, and “special deals” to close sales.

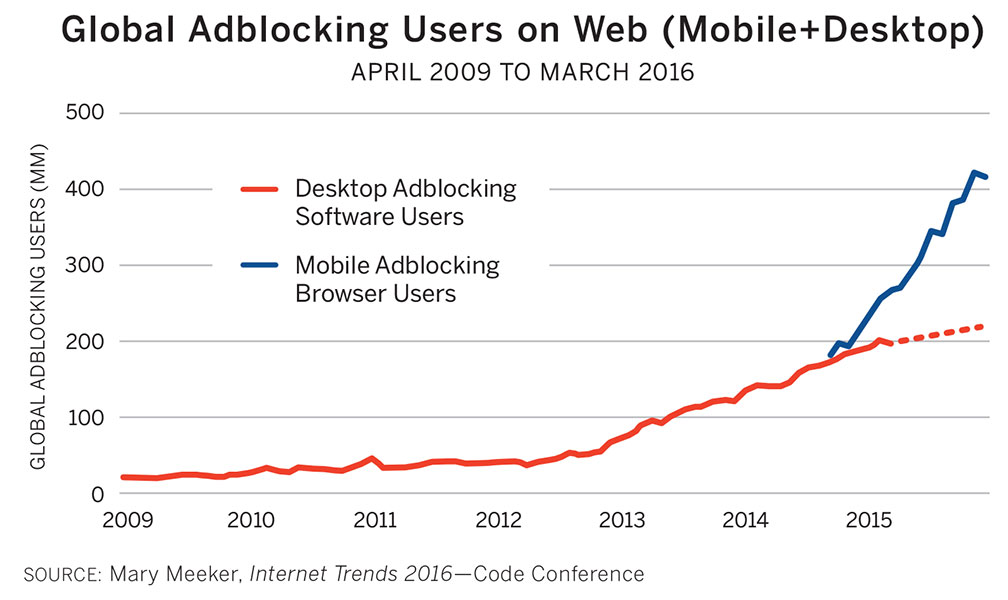

Factor #9: Mobile ad blockers shut out revenue

Consumers, desiring fast load times and uninterrupted access to content, can now download ad-blocking software. Its adoption rate has been running at between 10 percent (Japan) and 38 percent (Poland) to date, but its use is highest among young adults and those who consume news the most. 29 Moreover, it is now baked into the iPhone’s DNA, which last year enabled ad-blocking extensions to work in Safari iOS9. In the absence of user-paid content, or royalties for content use paid by other platforms, publishers find it deeply worrying that access to ad revenues will also be blocked.

In fact, publishers are irate. And they are even more angered since Adblock Plus, one of the largest ad-blockers, developed “Acceptable Ad” criteria setting standards for non-intrusive mobile advertising. It allows advertisers and publishers who have agreed to publish ads that abide by its criteria to be “whitelisted.” For that privilege, media companies pay Adblock Plus to release ads to their sites that advertisers had otherwise paid to deliver. Many view this as being taken hostage and forced to pay ransom. Adblock Plus, on its website, positions it more altruistically.

It posits the Acceptable Ad program is “beneficial in two ways: We hope that the initiative encourages the ad industry to pursue less intrusive ad formats and thus have a positive impact on the Internet as a whole. [And] it provides us with a viable source of revenue, which we need to be able to administer the Acceptable Ads program and continue development of a free product.” 30

Despite these fundamentally different viewpoints, the bottom line is that this is something consumers embrace. Ad-blockers are especially popular in emerging markets where users rely on expensive data plans. Ads that interrupt their experience, or cause content to load more slowly, or chew up their data use, are not tolerated. 31

Factor #10: And then there is Facebook

Derek Thompson, a senior editor at The Atlantic, has observed that “digital is eating legacy media, mobile is eating digital, and two companies, Facebook and Google, are eating mobile.” 32 Facebook currently has more than 1.7 billion users, or more than the combined populations of China and the United States.

And Facebook’s financial performance is sky-rocketing: in July 2016 Facebook announced its second-quarter profit exceeded two billion dollars, only six months after it reached the one-billion-dollar milestone. More than 90 percent of its users were on mobile phones and 84 percent of its sales during that quarter came from mobile advertising. 33 During the same period its live-video product, Facebook Live, took off, blurring the line between professional reporting and individual observation. “Live” received heightened visibility after its use in recording high-profile scenes, including a sniper attack on police in Dallas and a Minnesota woman’s footage of police shooting her boyfriend during a traffic stop. It also figured in the 2016 Presidential debates, when candidate Donald Trump’s campaign hosted a pre- and post-debate “broadcast” that initially reached an audience of 200,000, but ultimately reached more than 8.6 million Facebook viewers. 34

Facebook also owns two leading messaging apps that have almost supplanted SMS messaging and may even threaten email: WhatsApp and Messenger, each with more than a billion users. They keep people inside the mobile environment and, specifically, inside the Facebook environment. In a recent call with analysts, Mark Zuckerberg mentioned that the combination of Facebook and its Instagram and Messenger platforms (exclusive of WhatsApp) in total claim 50 minutes a day, on average, of users’ time—which is equivalent to roughly ten percent of non-working hours. And Facebook’s algorithm continues to evolve in order to capture even more time per day, more clicks per session, more time inside the platform. 35

With these compelling and overwhelming numbers, Facebook is no longer just a social media platform, it has become a dominant advertising environment in the mobile space, just as mobile becomes the dominant global advertising platform. It has the power to dictate terms and change the rules at will.

Yet Facebook has not, in the past, been a content creator. That fact has been central to its growth in profits: it is a cost-efficient business, more so than Google. Facebook has only recently begun commissioning content from other sources. In June 2016 Facebook began paying for a variety of media companies, celebrities, and others to produce videos that could be live streamed. That initiative was positioned as a test so that the company could learn more about that environment and compete more effectively with Snapchat and others. It was not, however, an altruistic way to share revenues with content creators.

For the most part, Facebook has always retained as much advertising revenue as it can. The more clicks it gets, the greater its audience engagement, the more revenue it makes from advertising. Thus, content producers view Facebook as a two-edged sword. They can build brand and exposure to their content by having it posted on the platform. They can engage audiences that might not otherwise see their work. And they can monetize that exposure by placing content fragments on their own Facebook pages and then harvest revenue when viewers link to the original websites.

The enormous downside? None of the original viewing of that content in the Facebook environment delivered revenue back to its creators. Enter Instant Articles, another two-edged sword.

During 2016, Facebook launched Instant Articles to bring stories from content producers into its own tent. That is, branded content from news organizations would appear in users’ News Feeds on their mobile devices and, when clicked, would open instantly, reportedly ten times faster than the process of referring users to websites outside the Facebook environment. The logic was that faster load times provide a much better user experience and allow people, in aggregate, to then access more content. The other rationale was that articles would potentially reach a vast mobile audience, far larger than those reached by individual publishers through their own distribution channels.

Again: more clicks, more money. And it would keep audiences inside the Facebook environment. The net effect, however, was that content creators would lose the initial social referrals sending users to their own websites where they could monetize the audience and have the opportunity to engage them more deeply in other content on their own sites.

The program launched formally in April 2016 and, from a starting list of invited participants, it was opened later to all publishers. To diffuse concerns about lost revenues from social referrals, Facebook set up terms allowing publishers to sell and serve their own ads in Instant Articles, retaining 100 percent of the revenue, and monetizing unsold inventory by displaying ads from Facebook’s Audience Network.

To date, Instant Articles (and its counterparts, Google Accelerated Mobile Pages and Apple’s Apple News, respectively) has been met with both guarded enthusiasm and caution on the part of large media organizations. Some promote an “all in” approach since Facebook now controls the worlds’ largest audience. They are pleased with the speed and experience users have with their content, and with the ability to expand their reach to the large universe reached by Facebook.

Others are concerned about losing control of their distribution channels and, with that, control over their own fate in terms of advertising and revenue generation. They worry that Facebook’s values of putting customer experience first could lead it to make decisions that downgrade the position of publishers within the platform and, thus, their own revenue. And they worry that they are incurring the hard costs of reporting, production, and brand development while Facebook retains the majority share of the revenues.

Those worries were underscored in June 2016, when shortly after opening Instant Articles to all publishers, Facebook announced a change to its algorithm that ranked stories from users’ families and friends over posts by publishers and brands on individuals’ News Feeds, its primary product. Publishers, angered that their referrals from Facebook had dropped following the switch to Instant Articles, also took umbrage that they frequently needed to pay Facebook to “sponsor” their stories and have them appear higher in the News Feed. 36

Note: This article focuses on Facebook more than Google, since data cited below—in conjunction with anecdotal reporting—show it plays a dominant role as a social media referrer to the types of news organizations supported by the media development community.

How News Outlets Are Performing in the Digital Advertising Market

The ten factors above contribute to a market environment that is arguably inhospitable to independent news outlets seeking national and local audiences—that is, unless those news outlets prepare for the new digital advertising environment, and that begins with data metrics.

Ross Settles of MDIF calls data metrics the “secret sauce of success” for media organizations in the new advertising environment, allowing them to track their audience’s preferences and respond in real time. And indeed, two of the most successful independent, on-line news sources operating—Rappler (http://www.rappler.com/) in the Philippines and Scroll (http://scroll.in/) in India—deeply engage with their metrics and adjust their content do the best job of expanding and engaging audiences.

Unfortunately, they are the exception. It has been difficult (and often impossible) to look at audience data across a wide number of the media organizations supported by the media development community. They typically do not participate in syndicated research studies or ratings surveys, nor do most have the financial resources to invest in routine proprietary research. Yet with the capabilities provided by Google Analytics, there is the possibility to both look at the audience metrics of individual sites, as well as to aggregate their data to analyze larger trends and establish benchmarks of performance.

The following section provides an analysis how media outlets are performing with digital and mobile audiences, based on one of one of the few sources of data available for such organizations. The conclusion from this analysis, in brief, is that they are not performing well. But this assessment should not be seen as definitive; on the contrary, it is the first step towards improving performance. After looking at the particular weaknesses of the outlets in the data set, this report makes some recommendations for how media producers and the organizations that support them can adapt to the rising tide of digital advertising.

Parsing the Available Data: Towards a Baseline of Audience Reach and Engagement

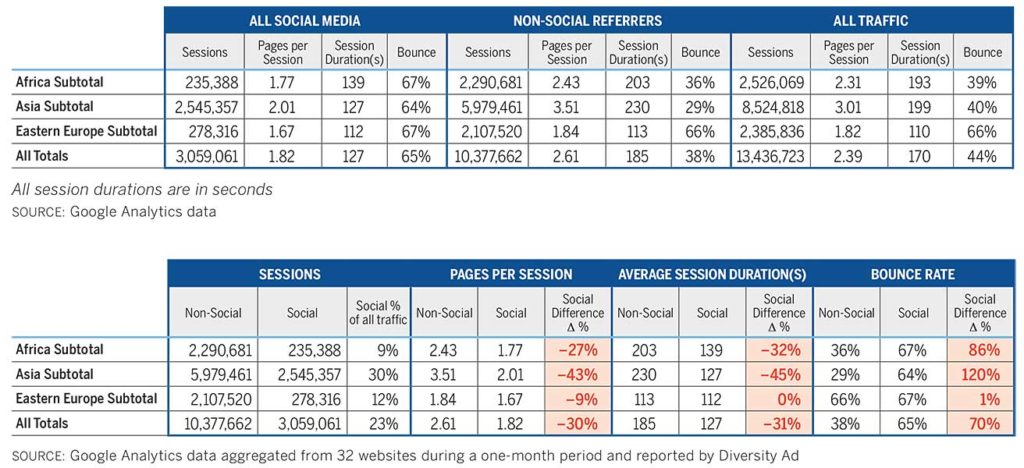

Diversity Ad, based in Copenhagen, represents independent news producers that are typically supported by the international community and are operating in more than 30 countries. Diversity’s network delivers more than 200 million paid ads per month to its partner sites. As such, it privately shares audience data and engagement metrics with potential advertisers. That also puts it in a unique position to take a fledgling look at online audience behavior by aggregating Google Analytics data from a wide range of those clients. Managing Director of Diversity Ad, Jason Lambert, provided such anonymous Google Analytics audience data for this report. 37

Although these data do not provide a complete look at the entire universe of independent news organizations served by the media development community, they do provide an initial, directional look at how typical partners perform.

Three areas were examined:

1. Where benchmarking data were available, how well did partners perform in comparison to other regional news sites?

2. What differences were observed in the engagement levels between people who visited websites directly versus those who came via social referral?

3. What were the primary channels of social referral?

The analysis produced the following findings.

■ Overall, traffic levels relative to in-country population sizes were low. Some of this is understandable in countries where Internet access is limited; where journalism-media compete with state actors; where their content is blocked and attacked; and where audiences— or the news organization—exist in exile. Other contributing factors, however, are more operational. A lack of technological prowess, an internal focus on news reporting without an equal focus on audience development, content that is negative or politicized, and websites that don’t function well in search engines, are reasons often cited by media development practitioners.

■ Social referrals yielded low engagement. Social users—those visiting a site because they followed a link from Facebook, Twitter or some other social media site—are notoriously unreliable. Once users click through, they often visit only the content they were directed to before backing out and closing the window. We found this to be equally true of the social users from our sample of sites, where engagement levels from social users were much lower than experienced from other non-social referrers (which included direct, referral, organic search, and other non-social media sources). In particular, the bounce rate was significantly higher. 38 High bounce rates, the percentage of single-page visits to a site where the user then backs out without going deeper into its pages, have important implications for a website publisher. Search engines rank pages and sites higher if they engage viewers to follow links and explore more content. When stories rank high in search engine results, they are exposed to more prospective viewers. If the website is trying to monetize its audience, luring its audiences to view multiple pieces of content —and also click through on advertising—is essential.

■ Fewer social referrals overall may limit audience growth. One distinctive finding was that in less developed areas, social referrals were not as significant a factor in driving traffic to partner websites as they are typically in more developed areas. Why would social referrals be less powerful? There are various, interlocking hypotheses. First, as noted above, there is a digital divide in terms of access to the Internet. Some of that is country-specific, in that an entire country may have low access. There can also be a digital divide between rural and urban populations (as in Kenya), 39 or between genders: ITU notes that there is a 31 percent gender gap in access to Internet in the least developed countries. 40 Other factors are at play, as well. In some of the poorest countries there is a lack of social networks operating in indigenous languages. Even when those exist, real-user name registration for both mobile devices and various social platforms has a chilling effect since they make individuals both visible and trackable. [footnote text=’GMSA has identified that prepaid SIM card registration linked to a personal registration is currently mandated in 90 countries, usually on the pretext that having a named individual associated with each mobile connection is an essential element of reducing criminal and anti-social behaviors. However, it has also found no empirical evidence showing a direct link between SIM card registration and crime reduction. Mandatory ‘Real Name’ Registration by Prepaid SIM Card Users: Considerations for Policymakers, GMSA website, http://www.gsma.com/ newsroom/blog/mandatory-real-name-registration-prepaidsim-card-users-considerations-policymakers/.’ And in countries where incomes are severely limited, mobile data costs can effectively undermine sharing.

■ Facebook is the near-universal leading source of social referral. The single exception to that was in Russian-language markets where Vkontakte (VK) dominated.

Hidden Metrics: The Consequence of Relying on a Social Media Platforms

However, these data are only part of a larger story.

A factor contributing to the low volume of referrals from social media to owned websites may be that organizations also use Facebook and other social media as primary distribution platforms: that’s where the audience is. For small operations focused on journalism, and lacking the resources, tools, and/or desire to operate a digital operation, posting to a social media platform can be a solution. It avoids the burden of building the platform and developing the audience; the newsrooms merely has to create the content.

Jane McElhone, an independent consultant and media analyst formerly with the Open Society Foundations (OSF), recently mapped the Burma media landscape. She observed that Facebook is the leading social referral source; sites such as The Irrawaddy and the regional media house Dawei Watch in Burma’s Tanintharyi Region typically post a short portion of an article on Facebook and then link back to their own sites. Yet page load times on owned websites in Burma are poor, frustrating users and eating up data charges.

Perhaps more importantly, given the recent explosion in mobile penetration, Facebook serves as the most vital source of breaking news and rapidly evolving events. During the dramatic 2016 elections, news posted directly to Facebook was the go-to source for coverage. It has quickly become a dynamic (and sometimes violently divisive) platform for commenting. Moreover, since audiences cannot use search engines such as Google in Burmese, unless people know English they go to Facebook first since they can post and comment in their own language.

In fact, McElhone observes, some people using Facebook aren’t aware it is part of the Internet as the country has leapfrogged desktop/laptop computing directly to mobile. They believe it is the Internet.

Yet despite its popularity in similar markets, it is not easy for publishers to monetize their Facebook content. In the case of highly political events, publishers do not typically sacrifice a large amount of revenue since advertisers avoid them, especially in independent media, so posting stories without harvesting revenue is a non-issue. For more typical content, some media houses operating in more obscure languages have embedded sponsored content into their news feed in violation of the Facebook Terms of Service agreement. And some are using Facebook’s Instant Articles.

Responding to publishers’ concerns, Facebook announced during the second half of 2016 that it is increasing the number of ways publishers can monetize their content directly within the Facebook environment.

■ It is offering larger and different types of ads that publishers can use within the Instant Article environment on mobile devices, allowing them greater flexibility in the ads sold directly to customers. Publishers retain 100 percent of the revenue from the ads they sell directly.

■ Sponsored content is now accepted under guidelines requiring that sponsors be tagged and identified. Again, publishers retain the revenue from these placements.

■ For companies allowing Facebook’s Audience Network to place ads within their Instant Articles, Facebook now supports two high-performing formats: video and carousel ads. Publishers will receive their usual share of the revenue— generally 30 percent— from this arrangement.

Even with these changes, publishers remain concerned about distributing their content in a platform they cannot control and where the rules frequently change.

Charting a Course: How Independent Media Can Improve Digital Distribution

The observations above should encourage sober reflection by news media and the institutions that support them. The shift to digital has redefined core business models for journalism. Although there are notable exceptions, it remains true that relatively few news consumers are willing to pay for online content, leaving media reliant on advertising revenue to support their organizations.

Publishers are now operating in a “distributed content” system where individual pieces of news are sent across multiple platforms, including ones not owned by the media organization. Their content is vacuumed up by online and mobile content aggregators, where those sites typically benefit financially from audience views, not the content producer. Even when ads are delivered to their sites, users can block them. And smaller media organizations exist outside the armature of advertising markets, invisible.

If these broad and deep shifts in the way news is produced, distributed, censored, and monetized challenge operations with the business sophistication of major media houses such as The New York Times, The Guardian, The Washington Post, and others, why would it be surprising that they present nearly insurmountable threats to independent news media that often operate under threat, in exile, or in opposition?

Given these challenges, it is imperative that the media development community take the lead in helping its partners become more effective in the digital space, with priority placed on mobile. Although at present, digital divides exist between genders, geographies, and age groups, those are dissolving. The trend-lines in the larger world of advertising and information consumption favor digital media.

What independent news media and the media development community can do

■ Consolidate—it is inevitable in the digital arena. While the smaller journalism houses served by the media development community are unlikely to ever achieve scale—their reporting is too narrow, their markets often too shallow —they could benefit from consolidated infrastructure. The media development community could create an organization to centralize platform development; support mobile deployment; harvest, analyze, and report metrics; deliver advertising services; create self-marketing strategies; and advocate with social media platforms and advertising actors. Time—and investment—have already proven that adequate capacity cannot always be built at the individual unit level.

■ Data. Metrics. Data. Metrics. These are the heart of effective media management today. They touch every aspect of journalism, from content to monetization. No matter how good it is, content is irrelevant if it fails to connect with an audience. The way to know what is working —and not working—is to be on top of the data. An important aspect of newsroom training by media development practitioners should be to focus on this area and help do field testing. What raises engagement? How do load times affect the bounce rate? What types of content attract target audiences? Which fail to connect? Another powerful tool would be to require that each news organization that receives media development support shares its data with a central third-party organization. If these data were captured, they would offer powerful insights into the effectiveness of and reach of independent news sites.

1. First, this approach could help highlight gender gaps in audiences and identify content approaches that build reach among women.

2. Second, it could set performance benchmarks and identify best practices which, when shared with the news organizations—and aggregated regionally or by other characteristics—would help guide news and engagement strategies.

3. Third, it would help the donor/funder community understand the impact of its investments and build accountability.

■ Pivot to digital, with mobile as the platform. We must understand mobile’s strengths and the paths to monetization. We must help our partners develop effective strategies for increasing their reach and engaging audiences in mobile environments. These partners, whether in postcommunist countries, developing nations, or in countries where governments use the world’s most sophisticated techniques to suppress their voices, deserve to be heard. Yet their voices are too often silenced by distributing their messages in the wrong mediums, or when using technologies they do not fully understand or embrace.

■ Digital craftsmanship matters. Some journalists argue that good journalism is the same on all platforms, that a reporter should be platform-agnostic; there is no need to train differently about how to report effectively in the mobile age. Some are blind to their audiences and only see their mission. These are arguments for an earlier time. Journalists have always been trained on reporting in the context of platforms: what journalist does not know how to structure a story for print? In an era of distributed content, they need to understand the craftsmanship of structuring it in ways that engage and retain audiences.

Footnotes

- Pew Research Center, “Communications Technology in Emerging and Developing Nations,” Global Attitudes and Trends, (2015). http://www.pewglobal.org/2015/03/19/1- communications-technology-in-emerging-and-developingnations/. The research found that “beyond smartphone ownership, cell phone ownership more broadly is very common, with a median of 84 percent in emerging and developing nations owning some type of cell phone. In eight emerging and developing countries, about nine-in-ten or more own mobile phones, comparable to the 90 percent of Americans with cell phones. Unlike other technologies, people in sub-Saharan African nations, including Nigeria, Senegal and Ghana, use mobile phones at similar rates to the rest of the emerging and developing world. Pakistan is the only country surveyed where less than half (47 percent) have a mobile phone.”

- Thomas Baerthlein, “Combatting Online Hate Speech in Burma,” Medium.com, accessed November 12, 2016, https:// medium.com/local-voices-global-change/combatting-onlinehate-speech-in-Burma-b8047d965c55#.gv9ip6eeh. The author noted that “posts widely shared on Facebook, such as fake news about rapes that never occurred, have helped inflame sectarian Buddhist-Muslim violence that has cost hundreds of lives in various parts of Burma since 2012.”

- Reporters Without Borders, “A ‘Deep and Disturbing’ Decline in Media Freedom,” World Press Freedom Index, https://rsf.org/en/ deep-and-disturbing-decline-media-freedom

- Ibid.

- Mark Nelson, Captured News Media: The Case of Turkey (Introduction) Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance, 2015). http://www. centerforinternationalmediaassistance.org/resource/capturednews-media-turkey/

- Goran Cetinić, Serbia (Washington, DC: IREX Media Sustainability Index, 2016). https://www.irex.org/sites/default/ files/pdf/media-sustainability-index-europe-eurasia-2016- serbia.pdf.pdf. During 2015, Serbia’s indicators declined in all five main categories in the MSI: freedom of speech, professionalism of journalists, diversity of sources, institutions of media support and economic self-sustainability, with freedom of the press and self-sustainability recording the greatest losses.

- Nelson, Captured News Media.

- Xinhua, “China’s Xi Underscores CPC’s Leadership in News Reporting,” Xinhua, February 19, 2016. http://news.xinhuanet. com/english/2016-02/19/c_135114305.htm

- Shanthi Kalathil, Beyond the Great Firewall (Washington DC: Center for International Media Assistance, 2017)

- Anne Nelson, CCTV’s International Expansion: China’s Grand Strategy for Media? (Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance, 2013). http://www. centerforinternationalmediaassistance.org/wp-content/ uploads/2015/02/CIMA-China-Anne-Nelson_0.pdf

- Filip Noubel, Innovation Advisor, Prague Civil Society Centre, and Innovation Advisor and Legal Representative, International Center for Communication Development (ICCD), interview with the author via Skype, July 22, 2016.

- Ross Settles, Senior Advisor Digital Media, MDIF, interview with the author via Skype, July 31, 2016.

- Pew Research Center, State of the News Media 2016 (Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, 2016). http://www. journalism.org/2016/06/15/state-of-the-news-media-2016/

- Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, David A.L. Levy, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen, Reuters Institute for Digital News Report (Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, 2016). https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/ Digital-News-Report-2016.pdf.

- Mary Meeker, “Internet Trends 2016 – Code Conference,” Presentation on Kleiner, Perkins, Caufield, Byers, accessed October 2016, http://www.kpcb.com/blog/2016-Internettrends-report.

- GMSA Intelligence, “Mobile Connectivity Index,” GMSA website, accessed October 2016, http://www.mobileconnectivityindex. com/ with global unique mobile user data updated in real time.

- International Telecommunication Union (ITU), “ICT Facts and Figures 2016,” https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/ Documents/facts/ICTFactsFigures2016.pdf and “ICT-Eye,” its portal for ICT data and statistics, http://www.itu.int/net4/itu-d/ icteye/.

- ITU, “ICT services getting more affordable – but more than half the world’s population still not using the Internet,” http://www.itu.int/en/mediacentre/Pages/2016-PR30.aspx

- Nanjala Nyabola, “Facebook’s Free Basics is an African Dictator’s Dream, Foreign Policy, October 27, 2016. https:// foreignpolicy.com/2016/10/27/facebooks-plan-to-wire-africais-a-dictators-dream-come-true-free-basics-Internet/.

- WAN-IFRA, World Press Trends, 35.

- Zenith Optimedia, Advertising Expenditure Forecasts, March 2016, http://www.zenithoptimedia.com/wp-content/ uploads/2016/03/Adspend-forecasts-March-2016-executivesummary.pdf

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Lara O’Reilly, “The 30 Biggest Media Companies in the World,” Business Insider, May 31, 2016 (Cites data from Zenith Optimedia, 2016 Top Thirty Global Media Owners with rankings of the world’s biggest media companies organized by revenue from financial year 2013, the most recent year for which consistent data were available from publicly-listed companies). http://www.businessinsider.com/the-30-biggest-media-ownersin-the-world-2016-5.

- Disney, “About US” Disney/ABC Television Group company website, accessed October 2016, http://www.disneyabcpress. com/disneyabctv/about-us/disney-channels/.

- McKinsey & Company, Global Media Report 2015: Global Industry Overview (2015). http://www.mckinsey.com/ industries/media-and-entertainment/our-insights/globalmedia-report-2015

- Ibid., 5.

- Interview, “Martin Sorrell on What’s Next,” Harvard Business Review, March, 2013. https://hbr.org/2013/03/martin-sorrellon-whats-next

- Newman et al., Reuters Institute Report, 8.

- Adblock Plus, “Allowing Acceptable Ads in Adblock Plus,” accessed August 3, 2016, https://adblockplus.org/acceptableads.

- Settles, Interview.

- Derek Thompson, “How Mobile Today is Like TV Six Decades Ago,” The Atlantic, June 15, 2016, http://www.theatlantic.com/ business/archive/2016/06/mobile-is-eating-everything/487148/

- Deepa Seetharaman, “Facebook Rides Mobile-Ad Surge,” Wall Street Journal, July 28, 2016, B1. http://www.wsj.com/articles/ facebook-posts-strong-profit-and-revenue-growth-1469650289.

- Brian Stelter, “The Facebook Live Stream that could Presage Trump TV,” CNN Money, October 21, 2016. http://money. cnn.com/2016/10/20/media/trump-tv-presidential-debatefacebook-live/.

- 8 James B. Stewart, “Facebook has 50 Minutes of Your Time Each Day. It Wants More.”, New York Times, May 5, 2016, http:// www.nytimes.com/2016/05/06/business/facebook-bends-therules-of-audience-engagement-to-its-advantage.html?_r=0.

- Sophie Benjamin, “How Facebook is Screwing Over Digital Publishers (Including Crikey),” Crikey, October 28, 2016. https://www.crikey.com.au/2016/10/28/facebook-screwingdigital-publishers-including-crikey/.

- Methodology included aggregating one month of Google Analytics audience data from 32 websites (13.4 million sessions) in Africa, Central and East Asia, and Eastern Europe. Websites chosen were ones that have been aided by the media development community; many continue to receive on-going donor support. Benchmarking data compares their performance against other news sites of comparable size within the same country. On average, social referrals resulted in (30 percent) fewer pages per session than non-social referrals: 1.82 vs. 2.61. They also resulted in visits that were (31 percent) shorter than non-social referrals: 127 seconds per session versus 185. And, on average, social referrals resulted in 70 percent more single-page visits than non-social referrals: 65 percent versus 38 percent. The websites from Asia (11 websites sampled across four countries in Central and East Asia) showed the greatest disparity between social and non-social traffic in terms of page views. Session duration was affected relatively little compared to Africa (13 websites sampled across four countries). This could be a function of differences in Internet speeds, web page speed optimization, average page length, or simply user behavior. The Eastern European media showed the least disparity, with some having social traffic that performed above the site average. In some cases, this could be due to a site receiving a large number of referrals from proxies and referring websites that might not deliver the most engaged visitors. It’s important to note that the Eastern European data was from 9 websites across two former Soviet countries only, so it does not represent the entire region.

- Google Analytics definition of bounce rate: “Bounce Rate is the percentage of single-page sessions (i.e. sessions in which the person left your site from the entrance page without interacting with the page). There are a number of factors that contribute to a high bounce rate. For example, users might leave your site from the entrance page if there are site design or usability issues. Alternatively, users might also leave the site after viewing a single page if they’ve found the information they need on that one page, and had no need or interest in going to other pages.” https://support.google.com/analytics/ answer/1009409?hl=en

- Introduction to Financially Viable Media in Emerging and Developing Markets (Nairobi: WAN-IFRA, 2012), 5-6.

- ITU, “ICT Facts and Figures 2016”