It’s time to put media back at the core of development.

Almost any way you look at or measure them, conditions for the news media in developing countries are not improving.

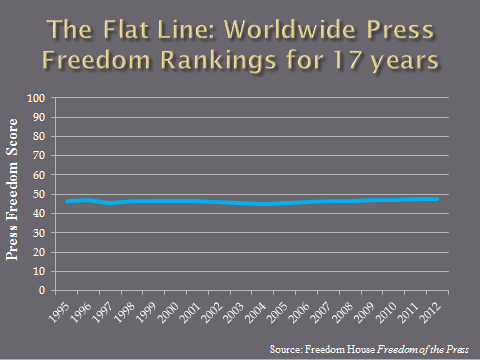

Despite exploding growth in mobile phones and Internet connectivity across the world, the creation of high quality, independent media is still a distant dream for most developing countries. Less than 14 percent of the world’s population lives in countries with a free press, according to a 2013 Freedom House report, and the world, on average, has produced a flat or downward sloping line of declining press freedom for most of the past two decades. IREX’s Media Sustainability Index also has also remained generally flat since it started tracking the performance of countries’ media systems in 2001. Yet almost everyone–from Nobel laureate economists to businesspeople and regular citizens–recognizes that better and more independent media in the developing world are critical to economic and social progress.

The Freedom on the Net scores by Freedom House have been inverted from their traditional 0-100 scale, where 0 is most free and 100 is least free. In this image, 0 is least free, and 100 is most free.

In my previous post, I promised to look at some of the global trends in the media development sector that will motivate CIMA’s strategy in the coming year. And among all the challenges that face the media development community today, nothing is more important than finding ways to change the trajectory of the flat line.

The good news is that a growing number of people are recognizing the importance of media as a component of development. At a meeting last week in Brussels, for example, members of Governance Network of the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee, the group of donors that provide more than $125 billion in annual development assistance, reaffirmed the importance of media to the overall development agenda, particularly in improving governance and accountability.

CIMA is pursuing three core lines of focus for its work.

1. Strengthening developing country leadership and ownership of media sector reforms

One of the lessons of the last 50 years of development work is that almost no reforms work without local buy-in and leadership of the reform process. Outsiders can offer advice, financial support, and set an example, but few countries have made sustainable progress without a strong country-led process of change.

Such leadership can come from many parts of a society, and parliamentarians, private sector advocates, and nongovernmental organizations can play an important role in raising the importance of independent media. But without strong political leadership at the top, real and sustainable change almost never happens.

In the media sector, countries such as Poland, the Czech Republic and South Korea have gone through such a country-driven process with much success. Tadeusz Mazowiecki (the first Polish prime minister after the fall of communism in 1989) and Nelson Mandela in South Africa are examples of national leaders who made a vigorous, independent media a core focus of their tenures in government. But today, such leadership is in short supply. Just think–can you name one leader of a developing country who is a strong, vocal supporter of free and independent media? On the contrary, in countries from Ecuador to Ukraine, national leaders are in open warfare with independent news media.

CIMA’s work program will continue to cooperate closely with programs funded by the National Endowment for Democracy, many of which are designed to strengthen the networks of country-level players who can be important advocates of change. NED supports not only hundreds of country-level projects–many of them for media–through its grants programs, but it hosts the International Forum for Democratic Studies and the World Movement for Democracy. These in turn cooperate with dozens of external partners in civil society and groups that work with governments and parliamentarians, such as the Community of Democracies. They can be key allies for media development work in countries. CIMA can help convene such groups for discussions on the role of the media. Moreover, our research and publications can support this work, explaining the value and defending the critical role of a vigorous and independent media.

2. Integration of media development work with the broader development agenda

Currently, the vast majority of media development initiatives are relatively isolated efforts, with few direct connections to other development work going on within countries. This means that organizations such as the World Bank–which is often trying to strengthen core institutions responsible for public finance management, the rule of law, or sectors like health or education–rarely see concrete links to needed reforms or investments in the media sector. Yet much evidence suggests that these links are critical both to the prospects for building a strong sustainable media sector and to the success of the broader development agenda.

In successful reformers such as Poland or South Korea, for example, public sector reforms and the creation of a competitive private sector went hand-in-hand with media reforms. In the 1990s, Poland laid the foundations for a strong media sector by ensuring that public sector and legal reforms ensured transparency, fair competition and a strong rule of law. This helped create an environment in which the media sector could thrive. At the same time, the growing news media helped translate the complex new laws and regulations of a market economy to Polish citizens and strengthened accountability between political leaders and Polish citizens. The private sector in turn invested heavily in what would became one of Poland’s most modern and competitive industrial sectors–media, entertainment, and advertising.

CIMA’s work will support this integration process by engaging in the international discussions now underway about improving development performance and setting new development goals to replace the Millennium Development Goals, which will expire in 2015. We need to support the process of setting explicit new global targets for improving governance, access to information, and transparency. These goals will create incentives to ensure that the more than $650 million in annual media development spending is well planned, executed and coordinated within the broader development framework. In turn, we are convinced that donors will find that investments in sustainable media development are good value for money and help ensure that other development spending is better tracked and monitored.

3. Data, diagnostics, research and learning

Lastly, CIMA will continue to devote energy to improving our understanding of the media in developing countries by supporting better media sector diagnostics, data, and research and by learning from the experiences of our partners. The whole media development community needs to expand the tools for better tracking and understanding the media sector, particularly at a time when the media business model is being uprooted by new technologies and news delivery methods. These include existing indicators such as the Freedom House freedom of the press indicator and the Media Sustainability Index. We also need to push for better integration of the media sector into all country-level diagnostic processes that are undertaken by developing countries and their donor partners. Better integration into governance and other diagnostics processes is the first step to a more serious and sustained approach to addressing the media sector’s development needs.

In addition to efforts to improve the quality of media programs in developing countries, we also need to find ways to convince the broader donor and private sector to invest in helping countries improve audience research and other market mechanisms that can help build more economically sustainable media institutions.

In sum, we face a challenging but exciting agenda. At a time when more people have access to mobile phones than to clean water, it is time to put media back at the core of development.

Comments (0)